January - February 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal's Discourses)

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal’s Discourses) Acknowledgement of Source Material: Ra. Ganapthy’s ‘Deivathin Kural’ (Vol.6) in Tamil published by Vanathi Publishers, 4th edn. 1998 URL of Tamil Original: http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-74.htm to http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-141.htm English rendering : V. Krishnamurthy 2006 CONTENTS 1. Essence of the philosophical schools......................................................................... 1 2. Advaita is different from all these. ............................................................................. 2 3. Appears to be easy – but really, difficult .................................................................... 3 4. Moksha is by Grace of God ....................................................................................... 5 5. Takes time but effort has to be started........................................................................ 7 8. ShraddhA (Faith) Necessary..................................................................................... 12 9. Eligibility for Aatma-SAdhanA................................................................................ 14 10. Apex of Saadhanaa is only for the sannyAsi !........................................................ 17 11. Why then tell others,what is suitable only for Sannyaasis?.................................... 21 12. Two different paths for two different aspirants ...................................................... 21 13. Reason for telling every one .................................................................................. -

Topic 5. the Nature of Jiva and Isvara. 1. Both Are Reflections. the Reflection of Consciousness in Maya Which Is Indescribable As Real Or Unreal Is Isvara

Topic 5. The nature of jiva and isvara. 1. Both are reflections. The reflection of consciousness in maya which is indescribable as real or unreal is Isvara. The reflection of consciousness in the infinite number of limited parts of maya, which have avarana and vikshepasakti and which are known as avidya is jiva. The part of maya with both avarana and vikshepa sakti is avidya. This is the view of Prakatarthakara. 2. Mulaprakriti is maya when it is predominantly pure sattva not overcome by rajas and tamas and it is avidya when it is impure sattva subordinated by rajas and tamas. The reflection in maya is Isvara and the reflection in avidya is jiva. This is the view of Swami Vidyaranya in Tattvaviveka, chapter 1 of Panchadasi. 3. Mulaprakriti itself with vikshepasakti being predominant is maya and is the upadhi of Isvara. With avarana sakti being predominent, mulaprakriti is avidya and it is the upadhi of jiva. Because of this, jiva has the experience of being ignorant, but not Isvara. This is the view of some. 4. Samkshepasariraka view—The reflection of consciousness in avidya is Isvara and the reflection in the mind is jiva. In the above views in which Isvara and jiva are reflections, the bimba (prototype) is pure consciousness (Brahman ) which is attained by the liberated. 5. Chitradipa view: Giving up the threefold aspect of Brahman as pure consciousness, Isvara, and jiva, a fourfold aspect is postulated. The reflection in ajnana tinged with the vasanas in the minds of all living beings, which is dependent on Brahman is Isvara. -

Divya Dvaita Drishti

Divya Dvaita Drishti PREETOSTU KRISHNA PR ABHUH Volume 1, Issue 4 November 2016 Madhva Drishti The super soul (God) and the individual soul (jeevatma) reside in the Special Days of interest same body. But they are inherently of different nature. Diametrically OCT 27 DWADASH - opposite nature. The individual soul has attachment over the body AKASHA DEEPA The God, in spite of residing in the same body along with the soul has no attach- OCT 28 TRAYODASHI JALA POORANA ment whatsoever with the body. But he causes the individual soul to develop at- tachment by virtue of his karmas - Madhvacharya OCT 29 NARAKA CHATURDASHI OCT 30 DEEPAVALI tamasOmA jyOtirgamaya OCT 31 BALI PUJA We find many happy celebrations in this period of confluence of ashwija and kartika months. NOV 11 KARTIKA EKA- The festival of lights dipavali includes a series of celebrations for a week or more - Govatsa DASHI Dvadashi, Dhana Trayodashi, Taila abhyanjana, Naraka Chaturdashi, Lakshmi Puja on NOV 12 UTTHANA Amavasya, Bali Pratipada, Yama Dvititya and Bhagini Tritiya. All these are thoroughly en- DWADASHI - TULASI joyed by us. Different parts of the country celebrate these days in one way or another. The PUJA main events are the killing of Narakasura by Sri Krishna along with Satyabhama, restraining of Bali & Lakshmi Puja on amavasya. Cleaning the home with broom at night is prohibited on other days, but on amavasya it is mandatory to do so before Lakshmi Puja. and is called alakshmi nissarana. Next comes completion of chaturmasa and tulasi puja. We should try to develop a sense of looking for the glory of Lord during all these festivities. -

Dvaita Vs. Advaita

> Subject: dvaita vs advaita > I have a very basic question to this very learned group. could someone please > tell us what exactly does dvaita and advaitha mean. kanaka One of the central questions concerning Vedanta philosophers is the relationship of the individual self to the Absolute or Supreme Self. The sole purpose for this question is to determine the nature of contemplative meditation and to determine whether moksha, the state of release, is something worth seeking. The Dvaita school, inaugurated by Madhvacharya (Ananda Tirtha), argues that there is an inherent and absolute five-fold difference in Reality -- between one soul and another, between the soul and God, between God and matter, between the soul and matter, and between matter and matter. These differences are not only individuations, but also inherent qualitative differences, i.e., in its essentially pure state, one individual self is _not_ equal to another in status, but only in genus. Therefore, there are inherently female jIvas, inherently male jIvas, brahmin jIvas, non-brahmin jIvas, and this differentiation exists even in liberation. Consequently, any sort of unity, whether it be mystical or ontological, between the individual self and God is impossible in Dvaita. Hence the term ``Dvaita'' or ``dualism''. Liberation consists of experiencing one's essential nature in parama padam as a reflection of God's glory. Such liberation is achieved through bhakti or loving devotion. The Advaita school, represented in its classical and most powerful form by Sankaracharya, argues that only the Absolute Self exists, _and_ all else is false. The universe and our existence as individuals is not _unreal_, mind you, but a false imposition on a real substrate, the non-dual, undifferentiated principle of consciousness. -

Is the 'Desire' Desirable

IS THE ‘DESIRE’ DESIRABLE (SWAMI SHUDDHABODHANANDA SARASWATI) ……………Continued from previous issue Disciple: Yes guro, but if I am not impertinent, may I ask another question? Guru : Go ahead. Disciple: It is true that the desire is a produced entity whereas saguna-brahma or Isvara is the Creator. Therefore we are told that Bhagavan’s statement ‘I am kaama’ does not mean an equation in the form of ‘Isvara is equal to kaama’. But the sruti itself tells us in the form of an equation: ‘Sarvam Brahman’ (Everything is Brahman). Is there not a contradiction? Guru : My dear, both these statements are from two different standpoints. The statement from the Gita takes for granted the Isvara, jagat and everything that is there in it at the level of vyavahara to describe Isvara’s glories which are useful to mumukshus and devotees in their saadhanaa. But the sruti declarations such as sarvam Brahma’ is only to reveal the immanent (sarvavyapi) nature of Brahman as the basis (adhisthana) of the entire adhyasta jagat. The jagat has no independent existence apart from Brahman. Such sruti statements do not intend to confer the status of nirvikari (changeless) Brahman on the vikari (ever-changing) jagat. The samanadhikaranya (juxtaposition) ‘sarvam Brahma’ is used only for the sake of dissolving Creation (prapancha-pravilapanartham) (Br.Su.bh.1-3-1). The principle is: though the jagat is non-different (ananya)from Brahman on account of the cause-effect relation between the two, the true nature of jagat is Brahman but the true nature of Brahman is not jagat (Br.Su.bh.2-1-9). -

Chapter 10, Verses 30 to 33,Baghawat Geeta, Class

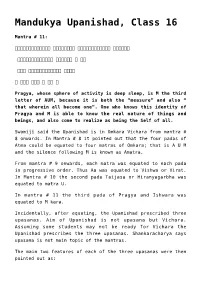

Mandukya Upanishad, Class 16 Mantra # 11: सुषुप्तस्थानः प्राज्ञो मकारस्तृतीया मात्रा िमतेरपीतेर्वा िमनोित ह वा इदं सर्वमपीितश्च भवित य एवं वेद ॥ ११ ॥ Pragya, whose sphere of activity is deep sleep, is M the third letter of AUM, because it is both the “measure” and also “ that wherein all become one”. One who knows this identity of Pragya and M is able to know the real nature of things and beings, and also come to realize as being the Self of all. Swamiji said the Upanishad is in Omkara Vichara from mantra # 8 onwards. In Mantra # 8 it pointed out that the four padas of Atma could be equated to four matras of Omkara; that is A U M and the silence following M is known as Amatra. From mantra # 9 onwards, each matra was equated to each pada in progressive order. Thus Aa was equated to Vishwa or Virat. In Mantra # 10 the second pada Taijasa or Hiranyagarbha was equated to matra U. In mantra # 11 the third pada of Pragya and Ishwara was equated to M kara. Incidentally, after equating, the Upanishad prescribed three upasanas. Aim of Upanishad is not upasana but Vichara. Assuming some students may not be ready for Vichara the Upanishad prescribes the three upasanas. Shankaracharya says upasana is not main topic of the mantras. The main two features of each of the three upasanas were then pointed out as: Upasana # 1: it is Aptehe and adimatva. Upasana # 2: Utakarsha and Ubhayatvat Upasana # 3: Mithi and Apithi . Once a nishkama upsana is performed by a manda bhakta his mind will be prepared. -

Patanjala Yoga Sutra, Bhagwad Gita, Kathopanishad). 1.2 Brief Introduction to Origin, History and Development of Yoga (Pre- Vedic Period to Contemporary Times

UNIT 1 Foundation of Yoga 1.1 Etymology and Definitions of Yoga (Patanjala Yoga Sutra, Bhagwad Gita, Kathopanishad). 1.2 Brief Introduction to origin, history and development of Yoga (Pre- Vedic period to contemporary times). 1.3 Yoga in Principle Upanishads. 1.4 Yoga tradition in Jainism: Syadvada (theory of seven fold predictions); Concept of Kayotsarga / Preksha meditation). 1.5 Yoga Tradition in Buddhism: concept of Aryasatyas (four noble truths). 1.6 Salient features and branches of Bharatiya Darshana (Astika and Nastika Darshana). 1.7 General introduction to Shad Darshana with special emphasis on Samkhya, Yoga and Vedanta Darshana. 1.8 Brief survey of Yoga in Modern and Contemporary Times (Shri Ramakrishna, Shri Aurobindo, Maharishi Raman, Swami Vivekananda, Swami Dayananda Saraswati, Swami Shivananda, Paramhansa Madhavadas ji, Yogacharya Shri T. Krishnamacharya). 1.9 Guiding principles to be followed by the practioner. 1.10 Brief Introduction to Schools of Yoga; Jnana, Bhakti, Karma, Raja & Hatha. 1.11 Principles and Practices of Jnana Yoga. 1.12 Principles and Practices of Bhakti Yoga. 1.13 Principles and Practices of Karma Yoga. 1.14 Concept and Principles of Sukshma Vyayama, Sthula Vyayama, Surya Namaskars and their significance in Yoga Sadhana. 1.15 Concept and Principles of Shatkarma: Meaning, Types, Principles and their significance in Yoga Sadhana. 1.16 Concept and Principles of Yogasana: Meaning, definition, types and their significance in Yoga Sadhana. 1.17 Concept and Principles of Pranayama: Meaning, definition, types and their significance in Yoga Sadhana. 1.18 Introduction to Bandha & Mudra and their health benefits. 1.19 Introduction to Yogic relaxation techniques with special reference to Yoga Nidra. -

Talks with Ramana

Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi Volume II 23rd August, 1936 Talk 240. D.: The world is materialistic. What is the remedy for it? M.: Materialistic or spiritual, it is according to your outlook. Drishtim jnanamayim kritva, Brahma mayam pasyet jagat Make your outlook right. The Creator knows how to take care of His Creation. D.: What is the best thing to do for ensuring the future? M.: Take care of the present, the future will take care of itself. D.: The future is the result of the present. So, what should I do to make it good? Or should I keep still? M.: Whose is the doubt? Who is it that wants a course of action? Find the doubter. If you hold the doubter the doubts will disappear. Having lost hold of the Self the thoughts afflict you; the world is seen, doubts arise, also anxiety for the future. Hold fast to the Self, these will disappear. D.: How to do it? M.: This question is relevant to matters of non-self, but not to the Self. Do you doubt the existence of your own Self? D.: No. But still, I want to know how the Self could be realised. Is there any method leading to it? M.: Make effort. Just as water is got by boring a well, so also you realise the Self by investigation. D.: Yes. But some find water readily and others with difficulty. M.: But you already see the moisture on the surface. You are hazily aware of the Self. Pursue it. When the effort ceases the Self shines forth. -

Mindfulness Worksheets, Talks, Ebooks and Meditations at �In�Fulne

Self Inquiry Date / Time So far today, have you brought kind awareness to your: Thoughts? Heart? Body? None of the Above PURPOSE/EFFECTS This is a meditation technique to get enlightened, i.e. “self realization.” By realizing who you are, the bonds of suffering are broken. Besides this goal, self-inquiry delivers many of the same benefits as other meditation techniques, such as relaxation, enhanced experience of life, greater openness to change, greater creativity, a sense of joy and fulfillment, and so forth. METHOD Summary Focus your attention on the feeling of being “me,” to the exclusion of all other thoughts. Long Version 1. Sit in any comfortable meditation posture. 2. Allow your mind and body to settle. 3. Now, let go of any thinking whatsoever. 4. Place your attention on the inner feeling of being “me.” 5. If a thought does arise (and it is probable that thoughts will arise on their own), ask yourself to whom this thought is occurring. This returns your attention to the feeling of being “me.” Continue this for as long as you like. This technique can also be done when going about any other activity. HISTORY Self inquiry or atma-vichara is an ancient Indian meditation technique. A version of it can be found, for example, in the Katha Upanishad, where it says: Get more free mindfulness worksheets, talks, eBooks and meditations at mindfulness MindfulnessExercises.com Self Inquiry The primeval one who is hard to perceive, wrapped in mystery, hidden in the cave, residing within the impenetrable depth— Regarding him as god, an insight gained by inner contemplation, both sorrow and joy the wise abandon. -

Against a Hindu God

against a hindu god Against a Hindu God buddhist philosophy of religion in india Parimal G. Patil columbia university press——new york columbia university press Publishers Since 1893 new york chichester, west sussex Copyright © 2009 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patil, Parimal G. Against a Hindu god : Buddhist philosophy of religion in India / Parimal G. Patil. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-231-14222-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-231-51307-4 (ebook) 1. Knowledge, Theory of (Buddhism) 2. God (Hinduism) 3. Ratnakirti. 4. Nyaya. 5. Religion—Philosophy. I. Title. BQ4440.P38 2009 210—dc22 2008047445 ∞ Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared. For A, B, and M, and all those who have called Konark home contents abbreviations–ix Introduction–1 1. Comparative Philosophy of Religions–3 1. Disciplinary Challenges–5 2. A Grammar for Comparison–8 3. Comparative Philosophy of Religions–21 4. Content, Structure, and Arguments–24 Part 1. Epistemology–29 2. Religious Epistemology in Classical India: In Defense of a Hindu God–31 1. Interpreting Nyaya Epistemology–35 2. The Nyaya Argument for the Existence of Irvara–56 3. Defending the Nyaya Argument–69 4. -

Shri Mularamo Vijayate Shri Laxmi Cha.Ndralaparameshvari Prasanna Shri Gururajo Vijayate

shrI mUlarAmo vijayate shrI laxmI cha.ndralAparameshvarI prasanna shrI gururAjo vijayate jIva kartrtva vichAra With many namaskaras to our teacher Sri Keshava Rao and at his suggestion, I will now attempt to summarize the questions and answer sessions that appear at the end of the teleconferences on jIva kartrtva lecture series. INTRODUCTION: Is jIva a kartru or not? If he is then how does one explain the Lord’s all doer-ship and independence ? If not, then how come the jIva experiences the fruits of actions not done by the jIva? These questions are at the heart of the jIva kartrtva discussion. These and many more similar questions that are an offshoot of the above questions are elaborately discussed in the kartrtvAdhikaraNa in the Brahma Sutras by Bhagavan Vedyavyasa. That the issue of jIva kartrtva is of substantial importance is indicated by the fact that kartrtvAdhikaraNa, comprising 10 sutras, is the second largest adhikaraNa or section in the Brahma Sutras. It occurs in the second Adhyaya third Pada of the Brahma Sutras. Sri Keshava Rao has elected to explain jIva kartrtva vichara by analyzing the kartrtvAdhikaraNa. Sriman Madhvacharya has commented upon the Sutras. His commentary has been commented upon by the luminaries of our tradition, including Sri Jayatirtha Muni, Sri Raghottama Tirtha Swamiji and Sri Raghavendra Swamiji. Detailed Sanskrit texts of the Bhashya and the sub-commentaries have already been distributed. An English translation of the Acharya’s bhashya by Sri S. Subba Rao, published in 1904 has also be distributed and could be a good review of Sri Keshava Rao’s lectures. -

Fundamental Concepts of Hinduism

Fundamental Concepts of Hinduism My Salutations to all Devas-Rishis-Pithrus OM DEDICATED TO LORD YAMA, MARKANDEYA, NACHIKETAS, SAVITRI AND NANDI, THE ETERNAL ATTENDANT OF LORD SIVA, WHO HAVE ALL UNRAVELLED THE MYSTERIES OF THE LIFE BEYOND DEATH OM "Hinduism is not just a faith. It is the union of reason and intuition that cannot be defined but is only to be experienced” - Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (1888-1975) ॐ अञानतिमिरा्ध्य ञाना्जनशलाकया । चषुु्िीमलिं यॳन ि्िॴ रीगरवॳु निः ॥ om ajnana-timirandasya jnananjnana salakaya caksur unmilitam yena tasmai sri gurave namah “I offer my most humble obeisance to my spiritual master who has opened my eyes which were blinded by ignorance with the light of knowledge.: [FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION] 1 INTRODUCTION The Information on this article “Fundamental Concepts of Hinduism” furnished here in is compiled from various mail friends, internet sites and elders who have knowledge on this subject. The documents referred in the net sites are quoted as told but not gone through by me for their authencity. Every effort has been taken not to leave essential points but to make the reading informative and interesting. Since the subject matter is lengthy and it could not be confined in one or two postings - it may appear lengthy. Hindu Dharma says, “To lead a peaceful life, one must follow the Sastras which are the rules of the almighty that cannot be changed by passage of time(i.e.kruta,thretha,dwapara&kali yuga).The almighty says, “Shruthi smrithi mamaivaagya yaasthaam ullangya varthathe | Aagya chhedi mamadhrrohi math bhaktopi na vaishnavahah||” Which means,vedas and sastras are my commands and one who surpasses these rules have breaken my laws and cannot be considered as my bhakta or a vaishnava.