LAG Ba-OMER: GET the POINT?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Ji Calendar Educator Guide

xxx Contents The Jewish Day ............................................................................................................................... 6 A. What is a day? ..................................................................................................................... 6 B. Jewish Days As ‘Natural’ Days ........................................................................................... 7 C. When does a Jewish day start and end? ........................................................................... 8 D. The values we can learn from the Jewish day ................................................................... 9 Appendix: Additional Information About the Jewish Day ..................................................... 10 The Jewish Week .......................................................................................................................... 13 A. An Accompaniment to Shabbat ....................................................................................... 13 B. The Days of the Week are all Connected to Shabbat ...................................................... 14 C. The Days of the Week are all Connected to the First Week of Creation ........................ 17 D. The Structure of the Jewish Week .................................................................................... 18 E. Deeper Lessons About the Jewish Week ......................................................................... 18 F. Did You Know? ................................................................................................................. -

Understanding Lag B'omer the Judaism Site

Torah.org Understanding Lag B'Omer The Judaism Site https://torah.org/counting-the-omer/lag-baomer/ UNDERSTANDING LAG B'OMER by Torah.org THE HOLIDAY OF LAG B'OMER The holiday of Lag B'Omer is the 33rd day of the Omer count. There are two reasons why this day is greeted with happiness, a break from the customs of mourning observed by many for much of the Omer period. The Talmud tells us that during the time of the great teacher Rebbe Akiva, a plague raged through his yeshiva, his rabbinical school, during the Omer. He lost 24,000 students during this time; even the great schools in Babylonia, and those of today, are not as large. Rebbe Akiva went on to teach five more students, and it is they who transmitted much of Jewish tradition on to future generations -- so one can only imagine what was lost because those 24,000 other students passed away. The Sages explain that the reason for the loss of these students was that despite their great learning, they were not respectful towards each other. Considering their towering scholarship, they should have showed more care and concern for the honor of their fellows. There are various traditions regarding the observance of mourning during the Omer, based upon the days when students passed away during the plague. But all agree that the deaths were interrupted on Lag B'Omer. There was, however, a very notable death on Lag B'Omer -- of one of Rebbe Akiva's great students, Rebbe Shimon ben Yochai (also known using the Aramaic form of "son of," Rebbe Shimon bar Yochai). -

Month Ly Newslet

Volume 6, Issue 8 May 2019 Iyar 5779 which together have)ג(, and gimel)ל( Pesach Sheni 2019 is observed on May 19 ters lamed (14 Iyar). the numerical value of 33. “BaOmer” means “of It is customary to mark this day by eating mat- the Omer.” The Omer is the counting period that z a h — if possible — and by omit- begins on the second day of Passover and culmi- ting Tachanun from the prayer services. nates with the holiday of Shavuot, following day 49. How Pesach Sheni Came About Hence Lag BaOmer is the 33rd day of the Omer A year after the Exodus, G‑d instructed the peo- count, which coincides with 18 Iyar. What hap- ple of Israel to bring the Passover offering on the pened on 18 Iyar that’s worth celebrating? afternoon of the fourteenth of Nissan, and to eat it that evening, roasted over the fire, together with What We Are Celebrating matzah and bitter herbs, as they had done the pre- Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, who lived in the sec- vious year just before they left Egypt. ond century of the Common Era, was the first to “There were, however, certain persons who had publicly teach the mystical dimension of become ritually impure through contact with a the Torah known as the Kabbalah, and is the au- dead body, and could not, therefore, prepare the thor of the classic text of Kabbalah, the Zohar. Passover offering on that day. They ap- On the day of his passing, Rab- proached Mosesand Aaron . and they said: bi Shimon instructed his disciples to mark the date ‘. -

Hebcal Diaspora 3987

January 3987 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Rosh Chodesh Sh'vat 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Tu BiShvat Provided by Hebcal.com with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License February 3987 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Rosh Chodesh Adar I Rosh Chodesh Adar I 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Purim Katan Provided by Hebcal.com with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License March 3987 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Rosh Chodesh Adar II Rosh Chodesh Adar II 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Erev Purim 29 30 31 Purim Shushan Purim Provided by Hebcal.com with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License April 3987 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Rosh Chodesh Nisan 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Yom HaAliyah 26 27 28 29 30 Erev Pesach Pesach I Pesach II Pesach III (CH''M) Provided by Hebcal.com with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License May 3987 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 Pesach IV (CH''M) Pesach V (CH''M) 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Pesach VI (CH''M) Pesach VII Pesach VIII 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Yom HaShoah Rosh Chodesh Iyyar Rosh Chodesh Iyyar 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Yom HaZikaron Yom HaAtzma'ut 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Pesach Sheni 31 Lag BaOmer Provided by Hebcal.com with a Creative Commons Attribution -

BIBLICAL GENEALOGIES Adam → Seth

BIBLICAL GENEALOGIES Adam → Seth → Enosh → Kenan → Mahalalel → Jared→ Enoch → Methuselah → Lamech → Noah (70 descendants to repopulate the earth after the flood – Gen. 10: 1- 32; 1 Chr. 1: 1-27; sons, grandsons, great grandsons): 1 2 The sons of Kenaz (1 Chr. 1: 36) joined the Jews by the tribe of Judah. His descendant was Jephunneh the Kenizzite, who begot Caleb (Num. 32: 12; Josh. 14: 6; 14; 1 Chr. 4: 13-15). Amalek was the father of the Amalekites. Descendants of Jacob (Gen. 46: 26-27) who came to Egypt: • From Reuben: Hanoch, Pallu, Hezron and Carmi. • From Simeon: Jemuel, Jamin, Ohad, Jakin, Zohar and Shaul (son of a Canaanite woman). • From Levi: Gershon, Kohath and Merari. • From Judah: Er ( in Canaan), Onan ( in Canaan), Shelah, Perez and Zerah; From Perez: Hezron and Hamul. • From Issachar: Tola, Puah (or Puvah, Masoretic text), Jashub (or Iob, Masoretic text) and Shimron. • From Zebulun: Sered, Elon and Jahleel. • Dinah (they were all sons of Leah , who had died in Canaan – Gen. 49: 31); total of 33 people (including Jacob). • From Gad: Zephon (Septuagint and Samaritan Pentateuch or Ziphion in Masoretic text), Haggi, Shuni, Ezbom, Eri, Arodi and Areli • From Asher: Imnah, Ishvah, Ishvi, Beriah and Serah (their sister). Beriah begat Heber and Malkiel (they were all sons of Zilpah , Leah’s maidservant); total of 16 people. • From Joseph: Manasseh and Ephraim. • From Benjamin: Bela, Beker, Ashbel, Gera, Naaman, Ehi, Rosh, Muppim, Huppim and Ard. They were all sons of Rachel , who had already died in Canaan – Gen. 35: 19), a total of 14 people. -

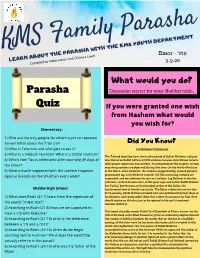

Parasha Quiz

ֱאמֹר - Emor tt sheva Levi ron and Eli y Rabbi Aa 5.9.20 Compiled b What would you do? Parasha Discussion starter for your Shabbat table.. Quiz If you were granted one wish from Hashem what would you wish for? Elementary: can become כהן Who are the only people for whom a (1 ?Did You Know ?כהן הגדול Tamei? What about the 2) What is Terumah and who gets to eat it? Lag BaOmer (Chabad.org) 3) What is a Kiddush Hashem? What is a Chillul Hashem? The Talmud describes how, during the period of Sefirat HaOmer a plague 4) Which Yom Tov is celebrated after counting 49 days of was visited on Rabbi Akiva’s 24,000 students because they did not behave with proper respect for one another. To commemorate the tragedy, certain the Omer? mourning customs are observed during this time. On the thirty-third day 5) What miracle happened with the Lechem Hapanim of the Omer count, however, the students stopped dying. (Lamed-gimmel, pronounced lag, is the Hebrew number 33.) The mourning customs are (special breads) on the Shulchan every week? suspended, and we celebrate the day as a holiday. Lag BaOmer is also the yahrtzeit, several decades later, of the great sage and mystic Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, best known as the principal author of the Zohar, the Middle/High School: fundamental text of Jewish mysticism. The Zohar relates that on the day of his passing, Rabbi Shimon revealed new and profound mystical ideas to 1) What does Rashi (21:1) learn from the repetition of his disciples, and commanded them that rather than mourn for him, they should rejoice on this day, just as he rejoiced in his soul’s imminent .reunion with G‑d ?"אמר ואמרת" the words 2) According to Rashi (21:8) how are we supposed to The famed chassidic master Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech of Dinov, known by the with Kedusha? title of his book as the Bnei Yissaschar, gives an interesting explanation for כהן treat a 3) According to Rashi (21:18) what is the difference the custom of lighting bonfires. -

The Covenanters of Damascus; a Hitherto Unknown Jewish Sect by George Foot Moore

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Covenanters of Damascus; A Hitherto Unknown Jewish Sect by George Foot Moore This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Covenanters of Damascus; A Hitherto Unknown Jewish Sect Author: George Foot Moore Release Date: April 12, 2010 [Ebook 31960] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE COVENANTERS OF DAMASCUS; A HITHERTO UNKNOWN JEWISH SECT*** The Covenanters of Damascus; A Hitherto Unknown Jewish Sect George Foot Moore Harvard University Harvard Theological Review Vol. 4, No. 3 July, 1911 Contents The Covenanters Of Damascus; A Hitherto Unknown Jewish Sect . .2 Footnotes . 59 [330] The Covenanters Of Damascus; A Hitherto Unknown Jewish Sect Among the Hebrew manuscripts recovered in 1896 from the Genizah of an old synagogue at Fostat, near Cairo, and now in the Cambridge University Library, England, were found eight leaves of a Hebrew manuscript which proved to be fragments of a book containing the teaching of a peculiar Jewish sect; a single leaf of a second manuscript, in part parallel to the first, in part supplementing it, was also discovered. These texts Professor Schechter has now published, with a translation and commentary, in the first volume of his Documents of Jewish Sectaries.1 The longer and older of the manuscripts (A) is, in the opinion of the editor, probably of the tenth century; the other (B), of the eleventh or twelfth. -

External Sources: Mishna 1:2 Gavriel Z

TRACTATE AVOT EXTERNAL SOURCES: MISHNA 1:2 GAVRIEL Z. BELLINO תלמוד בבלי מסכת יומא דף סט/א B. TALMUD TRACTATE YOMA 69A בעשרים וחמשה ]בטבת[ יום הר גרזים ]הוא[ דלא The twenty-fifth of Tebeth is the day of Mount Gerizim, on למספד יום שבקשו כותיים את בית אלהינו which no mourning is permitted. It is the day on which the Cutheans demanded the House of our God from Alexander מאלכסנדרוס מוקדון להחריבו ונתנו להם באו the Macedonian so as to destroy it, and he had given them והודיעו את שמעון הצדיק מה עשה לבש בגדי the permission, whereupon some people came and כהונה ונתעטף בבגדי כהונה ומיקירי ישראל עמו informed Simeon the Just. What did the latter do? He put ואבוקות של אור בידיהן וכל הלילה הללו הולכים on his priestly garments, robed himself in priestly מצד זה והללו הולכים מצד זה עד שעלה עמוד garments, some of the noblemen of Israel went with him carrying fiery torches in their hands, they walked all the השחר כיון שעלה עמוד השחר אמר להם מי הללו night, some walking on one side and others on the other אמרו לו יהודים שמרדו בך כיון שהגיע לאנטיפטרס side, until the dawn rose. When the dawn rose he זרחה חמה ופגעו זה בזה כיון שראה לשמעון ?[Alexander] said to them: Who are these [the Samaritans] הצדיק ירד ממרכבתו והשתחוה לפניו אמרו לו מלך They answered: The Jews who rebelled against you. As he גדול כמותך ישתחוה ליהודי זה אמר להם דמות .reached Antipatris, the sun having shone forth, they met When he saw Simeon the Just, he descended from his דיוקנו של זה מנצחת לפני בבית מלחמתי אמר carriage and bowed down before him. -

Jewish Holiday Guide Tu B’ Shvat 1 As Arepresentation Ofthenatural Cycle

Jewish Holiday Guide Tu B’Shvat 15th day of Shvat “…Just as my ancestors planted for me, so I will plant for my children (Talmud Ta’anit 23a).” Tu B’Shvat is a time when we celebrate the New Year for trees. It falls on the 15th of Shvat in the Hebrew calendar and it is a time for us to focus on our ecological responsibilities and the life cycle of renewal. The very first task that was assigned to humans by God was to care for the environment: ‘God took man and put him into the garden to work it and guard 1 it…’ (Genesis 1:15). In Israel, Tu B’shvat is usually celebrated by planting trees and holding the Tu B’shvat seder. Planting trees is a custom that was first held in 1884 in Israel due to the spiritual significance of the land of Israel and the agricultural emphasis that the Zionist brought with them to Israel. The Tu B’shvat seder is formed out of 4 sections for the 4 worlds as the Kabballah says: • The spiritual world of God represented by fire – Atzilut (nobility) • The physical world of human represented by earth – Assiyah (Doing) • The emotional world represented by air – Briyah (Creation) • The philosophical, thoughtful world represented by water – Yetzirah (Making) Each section of the seder also represents one of the four seasons, and mixtures of red and white wine are drunk in different amounts as a representation of the natural cycle. Tu B’ Shvat Tu Purim 14th day of Adar “The Feast of Lots” Purim is one of the most joyous and fun holidays on the Jewish calendar, as it celebrates the story of two heroes, Esther and Mordecai, and how their courage and actions saved the Jewish people living in Persia from execution. -

Ministério Seara Ágape Ensino Bíblico Evangélico

1 Ministério Seara Ágape Ensino Bíblico Evangélico https://www.searaagape.com.br/levitas_sacerdociolevitico.html BIBLICAL TOPICS FOR STUDY ––– LEVITES AND LEVITICAL PRIESTHOOPRIESTHOODDDD Author: Pastor Tânia Cristina Giachetti Levi was one of the twelve sons of the patriarch Jacob, and his descendants were separated from all their brethren to serve God as priests, especially the sons of Aaron. Levi begot Gershon, Kohath and Merari. Kohath begot Amram, and Izhar, and Hebron, and Uzziel. From the lineage of Amram, through Eleazar and Ithamar, the Lord separated the high priests. 2 Descendants of Levi [1 Chr. 6: 16-30; 31-48; 1 Chr. 15: 17-19; 1 Chr. 23: 1-32 (musicians of David *)]: 1) Gershon: Libni → generated offspring Shimei → generations → Berekiah → Asaph * 2) Kohath: Amram, Izhar, Uzziel, Hebron. Heman * is a descendant of Izhar. 3) Merari: Mahli → generated offspring Mushi → Mahli → generations → Ethan * (Jeduthun): 1 Chr. 15: 19; 1 Chr. 25: 1; 3. So, we can understand that the Levites were priests who served the Lord, but only those of the lineage of Amram, more specifically of Aaron, were fit to be high priests, for God Himself established to be so, when He spoke with Moses on Mount Sinai. One of the descendants of Eleazar (son of Aaron) gave his name to the eighth family (the family of Abijah) among the twenty-four divisions of the priests (1 Chr. 24: 10), of which Zechariah (Lk 1: 5), the father of John the Baptist, was part. High priests (1 Chr. 6: 1-15; 49-53): Aaron → Eleazar → Phinehas → Abishua → Bukki → Uzzi → Zerahiah → Meraioth → Amariah → Ahitub → Zadok (in the time of David) → Ahimaaz → Azariah → Johanan → Azariah (in the time of Solomon) → Amariah → Ahitub → Zadok → Shallum → Hilkiah → Azariah (2 Chr. -

Standing Together: a Social Justice Guide for Shavuot

Standing Together: A Social Justice Guide for Shavuot Shavuot commemorates the anniversary of the covenant between God and the Jewish people. On Shavuot, we remember the moment when we stood in the Presence of the Eternal One as we received the Torah and became a people, bound together by a sacred covenant. The period of the Omer, the forty-nine day bridge between Passover and Shavuot, and the evening of Shavuot itself, are traditionally times of preparation for this moment of re-living revelation. Hence the entire season of Shavuot encourages us to re- engage with Torah. It has been said that the entire Torah exists to establish justice. Thus, through the study of Torah and other Jewish texts, Shavuot offers us an opportunity to re-commit to tikkun olam. Moreover, aspects of the holiday of Shavuot and the period of the Omer lend themselves to the study of and engagement with particular social action issues. This guide offers programmatic suggestions for the Omer, Lag BaOmer, Tikkun Leil Shavuot, Shavuot day and confirmation. In particular, Lag BaOmer and Tikkun Leil Shavuot lend themselves to social action. During the Omer, many Jews refrain from celebrating simchahs; however, on Lag BaOmer, the thirty-third day of this period, this prohibition is lifted. Because so many festivities occur on this day, Lag BaOmer can be a time to consider ways to incorporate social action into our rejoicing. Tikkun Leil Shavuot, the late or all-night study session on Shavuot eve, offers a significant period of time that can be used for studying social justice and for engaging in tikkun olam. -

Reading the First Century

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament Herausgeber / Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber / Associate Editors Friedrich Avemarie † (Marburg) Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Hans-Josef Klauck (Chicago, IL) Tobias Nicklas (Regensburg) 300 Daniel R. Schwartz Reading the First Century On Reading Josephus and Studying Jewish History of the First Century Mohr Siebeck Daniel R. Schwartz, born 1952; 1980 PhD, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem; since 1995 Professor of Jewish History at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. ISBN 978-3-16-152187-4 ISSN 0512-1604 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliogra- phie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2013 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. www.mohr.de This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen, printed by Gulde-Druck in Tübin- gen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Arnaldo Dante Momigliano (1908–1987) In Memoriam Preface The movement toward reading Josephus through, and not merely reading through Josephus to external realities, now pro- vides the dominant agenda.1 The historian is not an interpreter of sources, although interpret he does. Rath- er, he is an interpreter of the reality of which the sources are indicative signs, or fragments.2 The title of this volume, “Reading the First Century,” is deliberately para- doxical, for what we in fact read are texts, not a period of time.