The Nordic Dimension in the Evolving European Security Structure and the Role of Norway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of European Union Accession in Democratisation Processes

The role of European Union accession in democratisation processes Published by Democratic Progress Institute 11 Guilford Street London WC1N 1DH United Kingdom www.democraticprogress.org [email protected] +44 (0)203 206 9939 First published, 2016 DPI – Democratic Progress Institute is a charity registered in England and Wales. Registered Charity No. 1037236. Registered Company No. 2922108. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee or prior permission for teaching purposes, but not for resale. For copying in any other circumstances, prior written permission must be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable.be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable 2 The role of European Union accession in democratisation processes Contents Foreword: ...................................................................................5 Abbreviations: ............................................................................7 Introduction: ..............................................................................8 I. European Union accession and democratisation – An overview .............................................................................11 A) Enlargement for democracy – history of European integration before 1993 ........................................................11 • Declaration on democracy, April 1978, European Council: .........................................................12 B) Pre accession criteria since 1993 and the procedure of adhesion ..........................................................................15 -

An Analysis of Conditions for Danish Defence Policy – Strategic Choices

centre for military studies university of copenhagen An Analysis of Conditions for Danish Defence Policy – Strategic Choices 2012 This analysis is part of the research-based services for public authorities carried out at the Centre for Military Studies for the parties to the Danish Defence Agreement. Its purpose is to analyse the conditions for Danish security policy in order to provide an objective background for a concrete discussion of current security and defence policy problems and for the long-term development of security and defence policy. The Centre for Military Studies is a research centre at the Department of —Political Science at the University of Copenhagen. At the centre research is done in the fields of security and defence policy and military strategy, and the research done at the centre forms the foundation for research-based services for public authorities for the Danish Ministry of Defence and the parties to the Danish Defence Agreement. This analysis is based on research-related method and its conclusions can —therefore not be interpreted as an expression of the attitude of the Danish Government, of the Danish Armed Forces or of any other authorities. Please find more information about the centre and its activities at: http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/. References to the literature and other material used in the analysis can be found at http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/. The original version of this analysis was published in Danish in April 2012. This version was translated to English by The project group: Major Esben Salling Larsen, Military Analyst Major Flemming Pradhan-Blach, MA, Military Analyst Professor Mikkel Vedby Rasmussen (Project Leader) Dr Lars Bangert Struwe, Researcher With contributions from: Dr Henrik Ø. -

Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers

January 2016 Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers Edited by Alessandro Marrone, Olivier De France, Daniele Fattibene Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers Edited by Alessandro Marrone, Olivier De France and Daniele Fattibene Contributors: Bengt-Göran Bergstrand, FOI Marie-Louise Chagnaud, SWP Olivier De France, IRIS Thanos Dokos, ELIAMEP Daniele Fattibene, IAI Niklas Granholm, FOI John Louth, RUSI Alessandro Marrone, IAI Jean-Pierre Maulny, IRIS Francesca Monaco, IAI Paola Sartori, IAI Torben Schütz, SWP Marcin Terlikowski, PISM 1 Index Executive summary ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 List of abbreviations --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Chapter 1 - Defence spending in Europe in 2016 --------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.1 Bucking an old trend ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.2 Three scenarios ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 1.3 National data and analysis ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.3.1 Central and Eastern Europe -------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.3.2 Nordic region -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

NATO Expansion: Benefits and Consequences

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2001 NATO expansion: Benefits and consequences Jeffrey William Christiansen The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Christiansen, Jeffrey William, "NATO expansion: Benefits and consequences" (2001). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8802. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8802 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ■rr - Maween and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of M ontana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission X No, I do not grant permission ________ Author's Signature; Date:__ ^ ^ 0 / Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. MSThe»i9\M«r«f»eld Library Permission Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NATO EXPANSION: BENEFITS AND CONSEQUENCES by Jeffrey William Christiansen B.A. University of Montana, 2000 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana 2001 Approved by: hairpers Dean, Graduate School 7 - 24- 0 ^ Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

European Defence Cooperation After the Lisbon Treaty

DIIS REPORT 2015: 06 EUROPEAN DEFENCE COOPERATION AFTER THE LISBON TREATY The road is paved for increased momentum This report is written by Christine Nissen and published by DIIS as part of the Defence and Security Studies. Christine Nissen is PhD student at DIIS. DIIS · Danish Institute for International Studies Østbanegade 117, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: +45 32 69 87 87 E-mail: [email protected] www.diis.dk Layout: Lone Ravnkilde & Viki Rachlitz Printed in Denmark by Eurographic Danmark Coverphoto: EU Naval Media and Public Information Office ISBN 978-87-7605-752-7 (print) ISBN 978-87-7605-753-4 (pdf) © Copenhagen 2015, the author and DIIS Table of Contents Abbreviations 4 Executive summary / Resumé 5 Introduction 7 The European Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) 11 External Action after the Lisbon Treaty 12 Consequences of the Lisbon changes 17 The case of Denmark 27 – consequences of the Danish defence opt-out Danish Security and defence policy – outside the EU framework 27 Consequences of the Danish defence opt-out in a Post-Lisbon context 29 Conclusion 35 Bibliography 39 3 Abbreviations CFSP Common Foreign and Security Policy CPCC Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability CSDP Common Security and Defence Policy DEVCO European Commission – Development & Cooperation ECHO European Commission – Humanitarian Aid & Civil Protection ECJ European Court of Justice EDA European Defence Agency EEAS European External Action Service EMU Economic and Monetary Union EU The European Union EUMS EU Military Staff FAC Foreign Affairs Council HR High -

Trine Bramsen Minister of Defence 24 September 2020 Via E

Trine Bramsen Minister of Defence 24 September 2020 Via e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Dear Minister, Thank you for your letter dated 12 May 2020. I am writing on behalf of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) Foundation and our US affiliate, which has more than 6.5 million members and supporters worldwide. We appreciate that the Danish armed forces have reduced their use of animals for live tissue training (LTT) from 110 animals in 2016 – as reported by the Danish Defence Command on 3 July 2020 pursuant to a citizen's request – to only nine animals in 2020. Considering how few animals have been used for LTT this year and given that a ratio of two to six students per animal (as stated in the new five-year "Militær traumatologi" LTT permit1) amounts to only 18 to 54 personnel undergoing the training this year, there is no significant investment in – or compelling justification for – using animals in LTT. Based on the information presented in this letter, we urge you to immediately suspend all use of animals for LTT while the Danish Armed Forces Medical Command conducts a comprehensive new evaluation of available non-animal trauma training methods to achieve full compliance with Directive 2010/63/EU and, in light of this evaluation, provide a definitive timeline for fully ending the Danish armed forces' use of animals for LTT. Danish Defence Command Does Not Have a List of LTT Simulation Models It Has Reviewed The aforementioned citizen's request asked for the following information: "[a] list of non-animal models that have been reviewed by the Danish Ministry of Defence for live tissue training (otherwise known as LTT or trauma training), with dates indicating when these reviews were conducted, and reasons why these non-animal models were rejected as full replacements to the use of animals for this training".2 1Animal Experiments Inspectorate, Ministry of Environment and Food. -

Death of an Institution: the End for Western European Union, a Future

DEATH OF AN INSTITUTION The end for Western European Union, a future for European defence? EGMONT PAPER 46 DEATH OF AN INSTITUTION The end for Western European Union, a future for European defence? ALYSON JK BAILES AND GRAHAM MESSERVY-WHITING May 2011 The Egmont Papers are published by Academia Press for Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations. Founded in 1947 by eminent Belgian political leaders, Egmont is an independent think-tank based in Brussels. Its interdisciplinary research is conducted in a spirit of total academic freedom. A platform of quality information, a forum for debate and analysis, a melting pot of ideas in the field of international politics, Egmont’s ambition – through its publications, seminars and recommendations – is to make a useful contribution to the decision- making process. *** President: Viscount Etienne DAVIGNON Director-General: Marc TRENTESEAU Series Editor: Prof. Dr. Sven BISCOP *** Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations Address Naamsestraat / Rue de Namur 69, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Phone 00-32-(0)2.223.41.14 Fax 00-32-(0)2.223.41.16 E-mail [email protected] Website: www.egmontinstitute.be © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent Tel. 09/233 80 88 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.academiapress.be J. Story-Scientia NV Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent Tel. 09/225 57 57 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be All authors write in a personal capacity. Lay-out: proxess.be ISBN 978 90 382 1785 7 D/2011/4804/136 U 1612 NUR1 754 All rights reserved. -

On the Way Towards a European Defence Union - a White Book As a First Step

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT STUDY On the way towards a European Defence Union - A White Book as a first step ABSTRACT This study proposes a process, framed in the Lisbon Treaty, for the EU to produce a White Book (WB) on European defence. Based on document reviews and expert interviewing, this study details the core elements of a future EU Defence White Book: strategic objectives, necessary capabilities development, specific programs and measures aimed at achieving the improved capabilities, and the process and drafting team of a future European WB. The study synthesizes concrete proposals for each European institution, chief among which is calling on the European Council to entrust the High Representative with the drafting of the White Book. EP/EXPO/B/SEDE/2015/03 EN April 2016 - PE 535.011 © European Union, 2016 Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies This paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Foreign Affairs and the Sub-Committee on Security and Defence. English-language manuscript was completed on 18 April 2016. Translated into FR/ DE. Printed in Belgium. Author(s): Prof. Dr. Javier SOLANA, President, ESADE Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics, Spain Prof. Dr. Angel SAZ-CARRANZA, Director, ESADE Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics, Spain María GARCÍA CASAS, Research Assistant, ESADE Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics, Spain Jose Francisco ESTÉBANEZ GÓMEZ, Research Assistant, ESADE Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics, Spain Official Responsible: Wanda TROSZCZYNSKA-VAN GENDEREN, Jérôme LEGRAND Editorial Assistants: Elina STERGATOU, Ifigeneia ZAMPA Feedback of all kind is welcome. Please write to: [email protected]. -

Military Security and Social Welfare in Denmark from 1848 to the Cold War Petersen, Klaus

www.ssoar.info The Welfare Defence: Military Security and Social Welfare in Denmark from 1848 to the Cold War Petersen, Klaus Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Petersen, K. (2020). The Welfare Defence: Military Security and Social Welfare in Denmark from 1848 to the Cold War. Historical Social Research, 45(2), 164-186. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.45.2020.2.164-186 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de The Welfare Defence: Military Security and Social Welfare in Denmark from 1848 to the Cold War Klaus Petersen∗ Abstract: »Die Wohlfahrtsverteidigung: Militärische Sicherheit und Soziale Wohlfahrt in Dänemark von 1848 bis zum kalten Krieg«. In this article, I discuss the connection between security and social policy strategies in Denmark from 1848 up to the 1950s. Denmark is not the first country that comes to mind when discussing the connections between war, military conscription, and social reforms. Research into social reforms and the role war and the military play in this field has traditionally focused on superpowers and regional powers. The main argument in the article is that even though we do not find policy-makers legitimizing specific welfare reforms using security policy motives, or the mili- tary playing any significant role in policy-making, it is nevertheless relevant to discuss the links between war and welfare in Denmark. -

European Union Candidate Countries: 2003 Referenda Results

Order Code RS21624 September 26, 2003 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web European Union Candidate Countries: 2003 Referenda Results name redacted Specialist in International Relations Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary The Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia held public referenda from March through September 2003 on becoming members of the European Union (EU). These nine countries plus Cyprus are expected to accede to the EU in May 2004, bringing the EU’s total membership to twenty-five. This report briefly analyzes the referenda results and implications. It will not be updated. For additional information see CRS Report RS21344, European Union Enlargement. Background to the Referenda The European Union is embarking on a major enlargement process that will expand the Union from fifteen to twenty-five members by mid-2004, and potentially more in the coming years. The current round of enlargement is notable for its size (which will expand the EU zone from 378 to over 450 million people) and inclusion of many former Communist bloc countries. Ten candidate countries – Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia – concluded accession negotiations in December 2002 and signed the Treaty of Accession on April 16, 2003 in Athens. Bulgaria and Romania aim to join the EU by 2007. Turkey is recognized as an EU candidate, and the countries of the western Balkans also seek eventual EU membership, although no target entry date has been identified for these states. From March through September 2003, nine of the ten acceding countries held public referenda on joining the EU according to their own constitutional procedures (Cyprus did not hold a referendum but ratified the accession treaty through a parliamentary vote). -

Contact to Delegates And

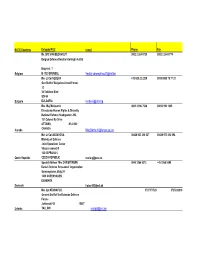

NATO Countries Delegate/POC e-mail Phone Fax Mr. SFC VAN EECKHOUT 0032 2 264 5735 0032 2 264 5774 Belgian Defence Kwartier Koningin Astrid Bruynstr. 1 Belgium B-1120 BRUSSEL [email protected] Mrs Lt Col NEDEVA +35 929 22 2235 0035 9888 79 77 21 Gen Staff of Bulgarian Armed Forces J2 34 Totleben Blvd SOFIA Bulgaria BULGARIA [email protected] Mrs. Maj McQuarrie 0061 3 996 7586 00613 992 1049 Directorate Human Rights & Diversity National Defence Headquarters HQ 101 Colonel By Drive OTTAWA, K1A 0K2 Canada CANADA [email protected] Mrs Lt Col GEDAYOVA 00420 923 210 327 00420 973 212 094 Ministry of Defence Joint Operations Center Vitezne namesti 5 160 00 PRAHA 6 Czech Republic CZECH REPUBLIC [email protected] Special Advisor Mrs CHRISTENSEN 0045 3266 5313 +45 3266 5599 Danish Defence Perosonnel Organization Sominegraven, Bldg 24 1439 COPENHAGEN DENMARK Denmark [email protected] Mrs Cpt KÜNNAPUU 3727171523 3725026019 General Staff of the Estonian Defence Forces Juhkentali 58 15007 Estonia TALLINN [email protected] Mr. Lt Col ADELL, 00331 72 69 20 89 00331 42 19 43 54 Etat-Major des Armees - ORH Rue Saint Dominique 14 00456 ARMEES France FRANCE [email protected] Cdr Mauersberger Federal Ministry of Defence Armed Forces Staff I 3 P.O. BOX 13 28 D- Germany 53003 BONN [email protected] Mrs Lt Col DIMITRIOU 0030 210 651 7648 Evolution Center Hellenic National General Staff Messogion Ave. 151 15500 HOLARGOS ATHENS Greece GREECE [email protected] 0030 210 6 57 62 46 Lt Col BALLAINE 0036 23 65 331 0036 23 65 111 / 26018 Közgazdasagi es Penzügyi Ügynökseg Aba uta 4. -

Steps to European Unity Community Progress to Date: a Chronology This Publication Also Appears in the Following Languages

Steps to European unity Community progress to date: a chronology This publication also appears in the following languages: ES ISBN 92-825-7342-7 Etapas de Europa DA ISBN 92-825-7343-5 Europa undervejs DE ISBN 92-825-7344-3 Etappen nach Europa GR ISBN 92-825-7345-1 . '1;1 :rtOQEta P'J~ EiiQW:rtTJ~ FR ISBN 92-825-7347-8 Etapes europeennes IT ISBN 92-825-7348-6 Destinazione Europa NL ISBN 92-825-7349-4 Europa stap voor stap PT ISBN 92-825-7350-8 A Europa passo a passo Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1987 ISBN 92-825-7346-X Catalogue number: CB-48-87-606-EN-C Reproduction authorized in whole or in pan, provided the source is acknowledged Printed in the FR of Germany Contents 7 Introduction 9 First hopes, first failures (1950-1954) 15 Birth of the Common Market (1955-1962) 25 Two steps forward, one step back (1963-1965) 31 A compromise settlement and new beginnings (1966-1968) 35 Consolidation (1968-1970) 41 Enlargement and monetary problems (1970-1973) 47 The energy crisis and the beginning of the economic crisis (1973-1974) 53 Further enlargement and direct elections (1975-1979) 67 A Community of Ten (1981) 83 A Community of Twelve (1986) Annexes 87 Main agreements between the European Community and the rest of the world 90 Index of main developments 92 Key dates 93 Further reading Introduction Every day the European Community organizes meetings of parliamentar ians, ambassadors, industrialists, workers, managers, ministers, consumers, people from all walks of life, working for a common response to problems that for a long time now have transcended national frontiers.