Psaudio Copper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Love Is a Metaphor: 99 Metaphors of Love

LOVE IS A METAPHOR: 99 METAPHORS OF LOVE https://www.thoughtco.com/love-is-a-metaphor-1691861 1. A Fruit Love is a fruit, in season at all times and within the reach of every hand. Anyone may gather it and no limit is set. (Mother Teresa, No Greater Love, 1997) 2. A Banana Peel I look at you and wham, I'm head over heels. I guess that love is a banana peel. I feel so bad and yet I'm feeling so well. I slipped, I stumbled, I fell. (Ben Weisman and Fred Wise, "I Slipped, I Stumbled, I Fell," sung by Elvis Presley in the film Wild in the Country, 1961) 3. A Spice Love is a spice with many tastes--a dizzying array of textures and moments. (Wayne Knight as Newman in the final episode of Seinfeld, 1998) 4. A Rose Love is a rose but you better not pick it. It only grows when it's on the vine. A handful of thorns and you'll know you've missed it. You lose your love when you say the word "mine."(Neil Young, "Love Is a Rose," 1977) 5. A Garden Now that you're gone I can see That love is a garden if you let it go. It fades away before you know, And love is a garden--it needs help to grow.(Jewel and Shaye Smith, "Love Is a Garden," 2008) 6. A Plant Love is a plant of the most tender kind, That shrinks and shakes with every ruffling wind. (George Granville, The British Enchanters, 1705) 7. -

80S 697 Songs, 2 Days, 3.53 GB

80s 697 songs, 2 days, 3.53 GB Name Artist Album Year Take on Me a-ha Hunting High and Low 1985 A Woman's Got the Power A's A Woman's Got the Power 1981 The Look of Love (Part One) ABC The Lexicon of Love 1982 Poison Arrow ABC The Lexicon of Love 1982 Hells Bells AC/DC Back in Black 1980 Back in Black AC/DC Back in Black 1980 You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC Back in Black 1980 For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) AC/DC For Those About to Rock We Salute You 1981 Balls to the Wall Accept Balls to the Wall 1983 Antmusic Adam & The Ants Kings of the Wild Frontier 1980 Goody Two Shoes Adam Ant Friend or Foe 1982 Angel Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Rag Doll Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Permanent Vacation 1987 Love In An Elevator Aerosmith Pump 1989 Janie's Got A Gun Aerosmith Pump 1989 The Other Side Aerosmith Pump 1989 What It Takes Aerosmith Pump 1989 Lightning Strikes Aerosmith Rock in a Hard Place 1982 Der Komimissar After The Fire Der Komimissar 1982 Sirius/Eye in the Sky Alan Parsons Project Eye in the Sky 1982 The Stand Alarm Declaration 1983 Rain in the Summertime Alarm Eye of the Hurricane 1987 Big In Japan Alphaville Big In Japan 1984 Freeway of Love Aretha Franklin Who's Zoomin' Who? 1985 Who's Zooming Who Aretha Franklin Who's Zoomin' Who? 1985 Close (To The Edit) Art of Noise Who's Afraid of the Art of Noise? 1984 Solid Ashford & Simpson Solid 1984 Heat of the Moment Asia Asia 1982 Only Time Will Tell Asia Asia 1982 Sole Survivor Asia Asia 1982 Turn Up The Radio Autograph Sign In Please 1984 Love Shack B-52's Cosmic Thing 1989 Roam B-52's Cosmic Thing 1989 Private Idaho B-52's Wild Planet 1980 Change Babys Ignition 1982 Mr. -

Theeditor-Epk.Pdf

Directed by Adam Brooks and Matthew Kennedy Written by Adam Brooks, Matthew Kennedy and Conor Sweeney Produced by Social Media sales Adam Brooks and Matthew Kennedy Twitter Producer’s Reps @theeditormovie Starring @astron6 Nate Bolotin Paz de la Huerta [email protected] Adam Brooks Facebook 310 909 9318 Facebook.com/editormovie Laurence R. Harvey Facebook.com/astron6 Mette-Marie Katz Samantha Hill [email protected] Udo Kier INTERWeb 323 983 1201 Jerry Wasserman www.theeditormovie.com Matthew Kennedy International Sales www.astron-6.com Conor Sweeney Dan Bern Paul Howell Tristan Risk CONTACT [email protected] Brett Donahue Kennedy/Brooks Inc. +44 (0)207 434 4176 738-3085 Pembina Hwy. Brent Neale Winnipeg MB R3T4R6 Sheila E. Campbell Kevin Anderson Matthew Kennedy Jasmine Mae [email protected] Tech Details Adam Brooks 99 min | Color | DCP | 2.39:1 | 5.1 | Canada | 2014 [email protected] LOGLINE A once-prolific film editor finds himself the prime suspect in a series of murders haunting a seedy 1970s film studio in this absurdist throwback to the Italian Giallo. SYNOPSIS Rey Ciso was once the greatest editor the world had ever seen. Since a horrific accident left him with four wooden fingers on his right hand, he’s had to resort to cutting pulp films and trash pictures. When the lead actors from the film he’s been editing turn up murdered at the studio, Rey is fingered as the number one suspect. The bodies continue to pile up in this absurdist giallo-thriller as Rey struggles to prove his innocence and learn the sinister truth lurking behind the scenes. -

Nektar ... Sounds Like This Mp3, Flac, Wma

Nektar ... Sounds Like This mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: ... Sounds Like This Country: Europe Style: Psychedelic Rock, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1267 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1954 mb WMA version RAR size: 1175 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 114 Other Formats: AAC ADX AU DMF MMF DXD FLAC Tracklist 1 Good Day 6:45 2 New Day Dawning 5:02 3 What Ya Gonna Do? 5:24 4 1-2-3-4 12:47 5 Do You Believe In Magic 7:17 6 Cast Your Fate 5:44 A Day In The Life Of A Preacher (13:01) 7a Preacher 7b Squeeze 7c Mr. H. 8 Wings 3:46 Odyssee (14:31) 9a Rons On 9b Never, Never, Never 9c Da-Da-Dum Companies, etc. Made By – Kdg Credits Producer – Nektar, Peter Hauke Written-By – Nektar Notes Repress of ... Sounds Like This, manufactured by kdg. Aluminum hub. Made in the EU. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Scanned): 4003099958227 Barcode (Text): 4003099 958227 Mastering SID Code: IFPI L173 Mould SID Code: IFPI 3077 Matrix / Runout: 725.548 29009003 #1 ASIN: B000026V8I Label Code: LC1421 Other (SPARS Code): AAD Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year ...Sounds Like This (2xLP, Bellaphon, Bacillus BDA 7501 Nektar BDA 7501 Germany 1973 Album) Records ...Sounds Like This (2xLP, Bacillus Records, BAC 2026 Nektar BAC 2026 Germany 1977 Album, RP) Bellaphon ...Sounds Like This (2xLP, Sireena 4003 Nektar Album, Ltd, Num, RE, Sireena Records Sireena 4003 Germany 2009 180) ...Sounds Like This (CD, Bellaphon, Bacillus 290-09-003 Nektar 290-09-003 Germany 1990 Album, RE) Records ...Sounds Like This (CD, Bellaphon, Bacillus 290·09·003 Nektar 290·09·003 Germany 1993 Album, RE, RP) Records Related Music albums to .. -

1; Iya WEEKLY

Platinum Blonde - more than just a pretty -faced rock trio (Page 5) Volume 39 No. 23 February 11, 1984 $1.00 :1;1; iyAWEEKLY . Virgin Canada becomes hotti Toronto: Virgin Records Canada, headed Canac by Bob Muir as President, moves into the You I fifth month flying its own banner and has become one of the hottest labels in the Cultu country. action THE PROMISE CONTINUES.... Contributing to the success of the label by th has been Culture Club with their albums of th4 Basil', Kissing To Be Clever and Colour By Num- bers. Also a major contributor is the break- W. out of the UB40 album, Labour Of Love, first ; boosted by the reggae group's cover of the forth Watch for: old Neil Diamond '60s hit, Red Red Wine. sampl "Over100,000 Colour By Numbers also t albums were shipped in the first ten days band' -the new Images In Vogue video of 1984 alone," said Muir. "The last Ulle40 Tt album only did about 13,000 here. Now, The' albun ... with Labour Of Love, we have the first gold Lust for Love album outside of Europe, and the success ships here is opening doors in the U.S. The record and c; broke in Calgary and Edmonton and started Al -Darkroom's tour (with the Payola$) spreading." Colour By Numbers has just surpassed quintuple platinum status in Canada which Ca] ...Feb. 17-29 represents 500,000 units sold, which took Va. about 16 weeks. The album was boosted and a new remixed 7" and 12" of San Paku by the hit singles Church Of The Poison Toros Mind, now well over gold, and the latest based single, Karma Chameleon, now well over of Ca the platinum mark in less than ten weeks prom This - a newsingle by Ann Mortifee of release. -

Il Meglio Del Rock Progressivo Italiano

Il meglio del rock progressivo italiano Scritto da Peppe Giovedì 29 Ottobre 2009 16:01 - I 20 MIGLIORI ALBUM DEL ROCK PROGRESSIVO ITALIANO Aria ('72) - Alan Sorrenti Banco del Mutuo Soccorso ('72) - Banco del Mutuo Soccorso Biglietto per l'Inferno ('74) - Biglietto per l'Inferno Celeste ('76) - Celeste Darwin! ('72) - Banco del Mutuo Soccorso Clowns ('73) - Nuova Idea Concerto Grosso ('71) - New Trolls Crac! ('75) - Area Dedicato a Frazz ('73) - Semiramis DNA ('72) - Jumbo Felona e Sorona ('73) - Le Orme Forse le lucciole non si amano più ('77) - Locanda delle Fate Giro di valzer per domani ('75) - Arti + Mestieri Inferno ('73) - Metamorfosi Io non so da dove vengo e non so dove mai andrò. Uomo è il nome che mi han dato ('73) - De De Lind Ys ('72) - Balletto di Bronzo Maxophone ('75) - Maxophone Palepoli ('73) - Osanna Per un amico ('72) - Premiata Forneria Marconi Zarathustra ('73) - Museo Rosenbach I 30 MIGLIORI BRANI DEL ROCK PROGRESSIVO ITALIANO A volte un istante di quiete - Forse le lucciole non si amano più ('77) - Locanda delle Fate Appena un po' - Per un amico ('72) - Premiata Forneria Marconi 'a zingara - Suddance ('78) - Osanna Aria - Aria ('72) - Alan Sorrenti Campagna - Napoli Centrale ('75) - Napoli Centrale Canto del capro - Melos ('73) - Cervello Confessione - Biglietto per l'Inferno ('74) - Biglietto per l'Inferno Forse le lucciole non si amano più - Forse le lucciole non si amano più ('77) - Locanda delle Fate Introduzione - Ys ('72) - Balletto di Bronzo Genealogia - Genealogia ('74) - Perigeo Il giardino del mago - Banco -

See Rules and Regulations

Event description * READ CAREFULLY THE RULES AND REGULATIONS * Among the most important Italian Fantastic film festivals, TOHORROR FILM FEST starts from cinema and then explores all possible means of communication, with the purpose of analysing contemporary society through the deforming lenses provided by the fantastic and horror culture. Thus, through the young authors’ videos and the films made by more expert directors, the meetings, the theatrical performances, the concerts, the art and comics exhibitions, we are enabled to interpret reality, filtering it through a most wild imagination. After Master Dario Argento, godfather of our first edition, other famous guests have honoured us with their presence in the last years: namely, Massimo Picozzi, Ruggero Deodato, Jean Rollin, Richard Stanley, Aldo Lado, Andreas Marchall, Richard Cherrington, Claudio Simonetti, Sergio Stivaletti, Antonio Caronia, John Duncan, Federico Zampaglione, Ivan Zuccon, Alda Teodorani, Claudio Chiaverotti, Alessandra C., John Carr, Lorenzo Bianchini, Forzani&Cattet and many others... Awards (no cash prices) - Miglior Cortometraggio / Best Short Film - Miglior Lungometraggio / Best Feature Film - Migliore sceneggiatura / Best Screenplay (Italian only) - Premio del pubblico al miglior cortometraggio / Audience Award for the best short - Premio del pubblico al miglior lungometraggio / Audience Award for the Best Feature - Premio “Anna Mondelli” per la miglior opera prima o talento giovanile / “Anna Mondelli” Award for the Best First Film or Young Talent - Premio “Antonio Margheriti” per la miglior inventiva artigianale / “Antonio Margheriti” Award for the most creative artisanal FX - Bloody Award ai migliori effetti speciali / Bloody Award to the best FX – Menzione Speciale del TOHorror / Special Mention of the TOHorror crew Rules & terms *READ CAREFULLY - IT'S SHORT I PROMISE* 1) The festival is structured in the following categories: Shortfilms (less than 30 minutes) Web series (episodes with a lenght inferior to 20 minutes each) Feature films (more than 70 minutes. -

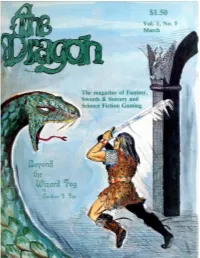

The Dragon Magazine #5

March ’77 DRAGON RUMBLES The eastern portion of the US is not the only area of the country to have suffered a blizzard this winter, though mine has been of a dif- ferent nature. A month or two ago, I placed a listing in WRITER‘S DIGEST, as a market for science fiction, fantasy and swords & sorcery. Within two weeks of that appearance, I have been inundated with a barrage of inquiries and unsolicited manuscripts, most of which aren’t right for these pages. But I’m reading, or having them read by Gary Jaquet , who has become my voluntary associate (meaning unpaid), every single one. What this means to all of the writers that have sent me submissions is that you should expect a response, but not soon. I have extended invitations to a number of authors of fantasy and science fiction games, other than D&D and EPT, to write on their creations for these pages. While we recognize that D&D started the fan- tasy gaming genre, there are now a number of science fiction and fan- tasy games available that we feel should be treated in this magazine. I extend this invitation to non-authors (of games) to do this also. I’m looking for articles on STELLAR CONQUEST, THE YTHRI, WBRM, GODSFIRE, STARSHIP TROOPERS, OUTREACH, Contents SORCERER, STARSOLDIER, GREEN PLANET TRILOGY, Witchcraft Supplement for D&D. ............................ 4 OGRE, MONSTERS-MONSTERS, VENERABLE DESTRUCTION More on METAMORPHOSIS ALPHA ....................... 10 and others. It’s time for THE DRAGON to expand its subject matter. I Featured Creature ....................................... 12 want to get into fantasy miniatures as well. -

Nektar Man in the Moon Mp3, Flac, Wma

Nektar Man In The Moon mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Man In The Moon Country: Germany Released: 1980 Style: Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1612 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1201 mb WMA version RAR size: 1753 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 191 Other Formats: VQF APE DTS VQF ADX VOC VOX Tracklist A1 Too Young To Die 4:17 A2 Angel 3:30 A3 Telephone 3:40 A4 Far Away 3:17 A5 Torraine 5:25 B1 Can't Stop You Now 4:18 B2 We 4:40 B3 You're Alone 4:05 B4 Man In The Moon 6:42 Companies, etc. Mastered At – Sterling Sound Printed By – Mohndruck Graphische Betriebe GmbH Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side 1): 202215 A - 1 / 80S Matrix / Runout (Side 2): 202215 B - 2 / 80S Matrix / Runout (Side 1 & 2): Made in Germany STERLING Rights Society: GEMA Label Code: LC0116 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Man In The Moon (LP, ARL 39082 Nektar Ariola ARL 39082 Italy 1980 Album) Man In The Moon (CD, none Nektar Not On Label (Nektar) none Russia 2002 Album, Unofficial) Man In The Moon (CD, WHD Entertainment, IECP-10059 Nektar IECP-10059 Japan 2006 Album, RE) Inc. Man In The Moon (CD, VP259CD Nektar Voiceprint VP259CD UK 2002 Album, RE, RM) Man In The Moon (LP, 6385248 Nektar Ariola 6385248 Greece 1980 Album) Related Music albums to Man In The Moon by Nektar Sterling Trio / Campbell And Burr - Avalon ("Down The Sunset Trail To Avalon") / Underneath The China Moon Nektar - Nektar Nektar - Live Nektar - .. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Chirkutt Jorja Smith Amazon Rainforest + BLACK History Month

whatson.guide Issue 348 Autumn 2019 Chirkutt Jorja Smith whatsOn Quiz Amazon Rainforest WIN Prizes + BLACK History Month + WIN Prizes GOR-JA XCLUSIVE What’s Jorja’s message for the next generation? BE A VETERAN’S HERO Every day our teams of SSAFA volunteers are making a lasting di erence to the lives of serving personnel, veterans and their families. Do something extraordinary and join us. Get in touch today to discuss a volunteering role that will make the most of your talents. Visit ssafa.org.uk/volunteer Registered as a charity in England and Wales Number 210760 in Scotland Number SCO38056 and in Republic of Ireland Number 20006082. Established 1885. S378.0919 01 XCLUSIVEON 005 Agenda> Student Awards 007 Live> Nugen 009 Fashion> Black History 011 Issue> 5 Ways 013 Interview> Jorja Smith 015 Report> Amazon Rainforest 017 Xclusive> Chirkutt 02 WHATSON 019 Action> Things To Do 020 Arts> Performance 023 Books> Top 10 Reads 025 Events> Festivals 027 Film> TV 029 Gigs> Clubs 031 Music> Releases 033 Sports> Games 03 GUIDEON 037 Best Picks> Briefing SAMIA OTHOI 039 Newson> Digest Multi-talented Samia is a 041 Column> Digest model, dancer and actress. She was second runner-up 043 Report> Issue in ‘Lux Channel i Superstar’ and in the top ten of 047 Classified> Jobs dance reality show ‘Shera 063 SceneOn> Reviews Nachiye’. Currently a model at Arong, she has acted in 065 Take10> City Life many tele-dramas, drama serials and is set to star in 066 WinOn> PlayOn films. Ads> T +44(0)121 655 1122 [email protected] Editorial> [email protected] About> WhatsOn: Progressive global local guide.