Summary of Dissertation Recitals Three Programs of Clarinet Music by Garret Ray Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sonatina for Cello and Piano by Zoltan Kodaly in the Light of Stile Evolution

Eurasian music science journal 2020 Number 2 2020/2 Article 11 12-31-2020 Sonatina for Cello and Piano by Zoltan Kodaly in the Light of Stile Evolution Galiaskar Bigashev The state conservatory of Uzbekistan, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uzjournals.edu.uz/ea_music Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Bigashev, Galiaskar (2020) "Sonatina for Cello and Piano by Zoltan Kodaly in the Light of Stile Evolution," Eurasian music science journal: 2020 : No. 2 , Article 11. DOI: doi.org/10.52847/EAMSJ/vol_2020_issue_2/A13 Available at: https://uzjournals.edu.uz/ea_music/vol2020/iss2/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by 2030 Uzbekistan Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eurasian music science journal by an authorized editor of 2030 Uzbekistan Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The works of Zoltan Kodai constantly attract the attention of listeners, performers and musicologists. Over time, we rethink his legacy, and in this process, the most valuable and artistically significant elements of the composer's work again convince us of the significance that Kodai's work has not only for Hungarian, but also for world musical culture. The master of Hungarian music has received widespread recognition as the creator of vocal, stage, choral works, as well as his pedagogical system, which significantly transformed the entire system of musical education in his homeland and was enthusiastically received by other countries. Such masterpieces as the opera "Hari Janos", symphonic "Dances from Galanta" and "Dances from Maroshsek", piano pieces, "Hungarian Psalm" became Kodai's trademark. -

Download Booklet

SIGCD656_16ppBklt**.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 19/11/2020 17:06 Page 1 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. 16 1 291.0mm x 169.5mm SIGCD656_16ppBklt**.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 19/11/2020 17:06 Page 2 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. rEDISCOvErEd British Clarinet Concertos Dolmetsch • Maconchy • Spain-Dunk • Wishart 1. Cantilena (Poem) for Clarinet and Orchestra, Op. 51 * Susan Spain-Dunk (1880-1962) ............[11.32] Concertino for Clarinet and String Orchestra Elizabeth Maconchy (1907-1994) 2. I. Allegro .....................................................................................................................................................................................................................[5.01] 3. II. Lento .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................[6.33] 4. III. Allegro ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. [5.32] Concerto for Clarinet, Harp and Orchestra * Rudolph Dolmetsch (1906-1942) 5. I. Allegro moderato ......................................................................................................................................................................................[10.34] -

Symposium Programme

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

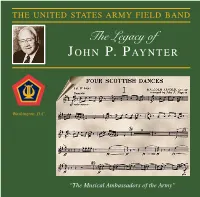

The Legacy of J O H N P

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND The Legacy of J OHN P. P AY N T E R Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” rom Boston to Bombay, Tokyo to Toronto, The United States Army Field Band has been thrilling audiences of all ages for more than half a century. As F the premier touring musical representative for the United States Army, this internationally-acclaimed organization travels thousands of miles each year presenting a variety of music to enthusiastic audiences throughout the nation and abroad. Through these concerts, the Field Band keeps the will of the American people behind the members of the armed forces and supports diplomatic efforts around the world. The Concert Band is the oldest and largest of the Field Band’s four performing components. This elite 65-member instrumental ensemble, founded in 1946, has per- formed in all 50 states and 25 foreign countries for audiences totaling more than 100 million. Tours have taken the band throughout the United States, Canada, Mexico, South America, Europe, the Far East, and India. The group appears in a wide variety of settings, from world-famous concert halls, such as the Berlin Philharmonie and Carnegie Hall, to state fairgrounds and high school gymnasiums. The Concert Band regularly travels and performs with the Soldiers’ Chorus, together presenting a powerful and diverse program of marches, overtures, popular music, patriotic selections, and instrumental and vocal solos. The organization has also performed joint concerts with many of the nation’s leading orchestras, including the Boston Pops, Cincinnati Pops, and Detroit Symphony Orchestra. -

Ithaca College Concert Band Ithaca College Concert Band

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-14-2016 Concert: Ithaca College Concert Band Ithaca College Concert Band Jason M. Silveira Justin Cusick Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Concert Band; Silveira, Jason M.; and Cusick, Justin, "Concert: Ithaca College Concert Band" (2016). All Concert & Recital Programs. 1779. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/1779 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College Concert Band "Road Trip!" Jason M. Silveira, conductor Justin Cusick, graduate conductor Ford Hall Thursday, April 14th, 2016 8:15 pm Program New England Tritych (1957) William Schuman I. Be Glad Then, America (1910–1992) II. When Jesus Wept 17' III. Chester More Old Wine in New Bottles (1977) Gordon Jacob I. Down among the Dead Men (1895–1984) II. The Oak and the Ash 11' III. The Lincolnshire Poacher IV. Joan to the Maypole Justin Cusick, graduate conductor Intermission Four Cornish Dances (1966/1975) Malcolm Arnold I. Vivace arr. Thad Marciniak II. Andantino (1921–2006) III. Con moto e sempre senza parodia 10' IV. Allegro ma non troppo Homecoming (2008) Alex Shapiro (b. 1962) 7' The Klaxon (1929/1984) Henry Fillmore arr. Frederick Fennell (1881–1956) 3' Jason M. Silveira is assistant professor of music education at Ithaca College. He received his Bachelor of Music and Master of Music degrees in music education from Ithaca College, and his Ph. -

Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets Of

Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927) By © 2017 Matthew Butterfield DMA, University of Kansas, 2017 M.M., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2011 B.S., The Pennsylvania State University, 2009 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Chair: Dr. Margaret Marco Dr. Colin Roust Dr. Sarah Frisof Dr. Eric Stomberg Dr. Michelle Hayes Date Defended: 2 May 2017 The dissertation committee for Matthew Butterfield certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927) Chair: Dr. Margaret Marco Date Approved: 10 May 2017 ii Abstract Léon Goossens’s virtuosity, musicality, and developments in playing the oboe expressively earned him a reputation as one of history’s finest oboists. His artistry and tone inspired British composers in the early twentieth century to consider the oboe a viable solo instrument once again. Goossens became a very popular and influential figure among composers, and many works are dedicated to him. His interest in having new music written for oboe and strings led to several prominent pieces, the earliest among them being the oboe quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927). Bax’s music is strongly influenced by German romanticism and the music of Edward Elgar. This led critics to describe his music as old-fashioned and out of touch, as it was not intellectual enough for critics, nor was it aesthetically pleasing to the masses. -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

Cbarber Repertoire 2020.Pdf

Carolyn A. Barber University of Nebraska-Lincoln Conducting Repertoire, 2001-present UNL Wind Ensemble 2020 [April 28 concert cancelled due to COVID-19 precautions on campus] March 11, Kimball Recital Hall Joan Tower, Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman No. 1 (1987) Victoria Bond, The Indispensable Man (2010) *Nebraska premiere performance Felicia Sandler, Rosie the Riveter (2000) *Nebraska premiere performance Jonathan Newman, Symphony No. 1: My Hands Are a City (2009) 2019 December 11, Kimball Recital Hall https://youtu.be/4HBj7rIC6vk Gustav Holst, Suite in E-flat (1909) Percy Grainger, arr. Perna, Mock Morris (1910/2016) Joshua Cutting, doctoral associate conductor J.S. Bach, arr. N. Falcone, Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor (1712/1969) Gustav Holst, Bach’s Fugue à la Gigue (1707/1928) Rubén Gómez, doctoral associate conductor Percy Grainger, Colonial Song (1919/1997) Paul Hindemith, Symphony in B-flat (1951) October 2, Kimball Recital Hall https://youtu.be/RkzJB7msUuY Stephen Montague, Intrada 1631 (2003) Donald Grantham, Circa 1600 (2018) Kathryn Salfelder, Crossing Parallels (2011) Bob Margolis, Terpsichore (1981) Roberto Sierra, arr. Scatterday, Tumbao from Sinfonia No. 3 (2005/2009) *Nebraska premiere performance [Spring semester sabbatical – Newell Scholar at Georgia College] 2018 December 5, Kimball Recital Hall https://youtu.be/OwTWlg7jmiI Larry Tuttle, Across the Divide (2018) Carter Pann, The Three Embraces (2013) Cindy McTee, California Counterpoint: The Twittering Machine (1993) Carter Pann, My Brother’s Brain: A Symphony for Winds (2011) Carter Pann, Floyd’s Fantastic Five-Alarm Foxy Frolic (2009) October 3, Kimball Recital Hall Bernard Rogers, Three Japanese Dances: Dance with Pennons (1933/1956) Jennifer Jolley, The Eyes of the World Are Upon You (2017) *Nebraska premiere performance Frank Ticheli, Amazing Grace (1994) Rubén Gómez, doctoral associate conductor David Maslanka, Symphony No. -

A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’S Clarinet Sonata

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata Kenneth T. Aoki Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Composition Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation Aoki, Kenneth T., "A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata" (1968). All Master's Theses. 1077. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1077 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SONATA WITH AN ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON OF A BRAHMS' AND HINDEMITH'S CLARINET SONATA A Covering Paper Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Music Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Education by Kenneth T. Aoki August, 1968 :N01!83 i iuJ :JV133dS q g re. 'H/ £"Ille; arr THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC CENTRAL WASHINGTON STATE COLLEGE presents in KENNETH T. AOKI, Clarinet MRS. PATRICIA SMITH, Accompanist PROGRAM Sonata for Clarinet and Piano in B flat Major, Op. 120 No. 2. J. Brahms Allegro amabile Allegro appassionato Andante con moto II Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano .............................................. 8. Heiden Con moto Andante Vivace, ma non troppo Caprice for B flat Clarinet ................................................... -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Views, Notes by The

Florida State University Libraries 2016 Analysis of Two Early Euphonium Concertos, Their Composers, and Their Impact on the Euphonium Repertoire Paul Thomas Dickinson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC ANALYSIS OF TWO EARLY EUPHONIUM CONCERTOS, THEIR COMPOSERS, AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE EUPHONIUM REPERTOIRE By PAUL DICKINSON A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music 2016 Paul Dickinson defended this treatise on April 11, 2016. The members of the supervisory committee were: Paul Ebbers Professor Directing Treatise Patrick Dunnigan University Representative John Drew Committee Member Christopher Moore Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………...iv CHAPTER ONE – JOSEPH HOROVITZ AND HIS EUPHONIUM CONCERTO OF 1972…...1 Early Life and Education………………………………………………………………….1 Career……………………………………………………………………………………...2 Joseph Horovitz’s Music…………………...………………....………………………......5 Modern Day……………………………………………………………………………….9 Historical Relevance……..................................................................................................10 Euphonium Concerto (1972)………..................................................................................11