Counting the Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TOWNHOUSE MEWS, GOLDHAWK ROAD Shepherds Bush W12

TOWNHOUSE MEWS, GOLDHAWK ROAD SHEPHERDS BUSH W12 TOWNHOUSE MEWS, GOLDHAWK ROAD SHEPHERDS BUSH W12 The architectural features throughout have resulted in clever and A bespoke development of just 12 contemporary homes set on the site thoughtful living areas with unique elements and appeal to each floor. of the historic and celebrated Townhouse Recording Studios, boasting a Fitted to luxury standards, the state-of-the-art specification features fine location in the heart of vibrant Shepherds Bush. underfloor heating throughout, walk-in wardrobes and stunning Defined as one of the most famous recording studios in the world, Italian designer kitchens. Extensive master bedroom suites often Townhouse was created by Richard Branson in 1978 and enjoyed enjoy a dedicated floor with dressing areas and spectacular subsequent ownership by the iconic creative labels EMI and Sanctuary bathroom suites and the houses have the additional advantage of Records. Artists that recorded at Townhouse Studios included Queen, multiple outdoor areas including some beautiful private roof terraces Phil Collins, The Jam, Coldplay, Duran Duran, Robbie Williams and accessible via remotely operated glass roof lights. Elton John, with Candle in the Wind, the fastest selling single of all time Goldhawk Road is a well-known and highly sought-after part of being created within its walls and the renowned ‘Stone Room’ making Shepherds Bush, close to Central London, providing an extensive use of its hallowed wall when recording Phil Collins’ ‘In The Air Tonight.’ array of exciting restaurants and bars, easy access to Chiswick and With a wealth of unique creative energy, this landmark address has the River Thames and a short walk from the outstanding Westfield been remastered to create cutting-edge mews houses that have been Shopping Centre. -

Toto's Shannon Forrest

WORTH WIN A TAMA/MEINL PACKAGE MORE THAN $6,000 THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE 25 GR E AT ’80s DRUM TRACKS Toto’s Shannon ForrestThe Quest For Excellence NEW GEAR REVIEWED! BOSPHORUS • ROLAND • TURKISH OCTOBER 2016 + PLUS + STEVEN WOLF • CHARLES HAYNES • NAVENE KOPERWEIS WILL KENNEDY • BUN E. CARLOS • TERENCE HIGGINS PURE PURPLEHEARTTM 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 CALIFORNIA CUSTOM SHOP Purpleheart Snare Ad - 6-2016 (MD).indd 1 7/22/16 2:33 PM ILL SURPRISE YOU & ILITY W THE F SAT UN VER WIL HE L IN T SP IR E Y OU 18" AA SICK HATS New Big & Ugly Big & Ugly is all about sonic Thin and very dry overall, 18" AA Sick Hats are 18" AA Sick Hats versatility, tonal complexity − surprisingly controllable. 28 holes allow them 14" XSR Monarch Hats and huge fun. Learn more. to breathe in ways other Hats simply cannot. 18" XSR Monarch With virtually no airlock, you’ll hear everything. 20" XSR Monarch 14" AA Apollo Hats Want more body, less air in your face, and 16" AA Apollo Hats the ability to play patterns without the holes 18" AA Apollo getting in your way? Just flip ‘em over! 20" AA Apollo SABIAN.COM/BIGUGLY Advertisement: New Big & Ugly Ad · Publication: Modern Drummer · Trim Size: 7.875" x 10.75" · Date: 2015 Contact: Luis Cardoso · Tel: (506) 272.1238 · Fax: (506) 272.1265 · Email: [email protected] SABIAN Ltd., 219 Main St., Meductic, NB, CANADA, E6H 2L5 YOUR BEST PERFORMANCE STARTS AT THE CORE At the core of every great performance is Carl Palmer's confidence—Confidence in your ability, your SIGNATURE 20" DUO RIDE preparation & your equipment. -

THE GARY MOORE DISCOGRAPHY (The GM Bible)

THE GARY MOORE DISCOGRAPHY (The GM Bible) THE COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS 1969 - 1994 Compiled by DDGMS 1995 1 IDEX ABOUT GARY MOORE’s CAREER Page 4 ABOUT THE BOOK Page 8 THE GARY MOORE BAND INDEX Page 10 GARY MOORE IN THE CHARTS Page 20 THE COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS - THE BEGINNING Page 23 1969 Page 27 1970 Page 29 1971 Page 33 1973 Page 35 1974 Page 37 1975 Page 41 1976 Page 43 1977 Page 45 1978 Page 49 1979 Page 60 1980 Page 70 1981 Page 74 1982 Page 79 1983 Page 85 1984 Page 97 1985 Page 107 1986 Page 118 1987 Page 125 1988 Page 138 1989 Page 141 1990 Page 152 1991 Page 168 1992 Page 172 1993 Page 182 1994 Page 185 1995 Page 189 THE RECORDS Page 192 1969 Page 193 1970 Page 194 1971 Page 196 1973 Page 197 1974 Page 198 1975 Page 199 1976 Page 200 1977 Page 201 1978 Page 202 1979 Page 205 1980 Page 209 1981 Page 211 1982 Page 214 1983 Page 216 1984 Page 221 1985 Page 226 2 1986 Page 231 1987 Page 234 1988 Page 242 1989 Page 245 1990 Page 250 1991 Page 257 1992 Page 261 1993 Page 272 1994 Page 278 1995 Page 284 INDEX OF SONGS Page 287 INDEX OF TOUR DATES Page 336 INDEX OF MUSICIANS Page 357 INDEX TO DISCOGRAPHY – Record “types” in alfabethically order Page 370 3 ABOUT GARY MOORE’s CAREER Full name: Robert William Gary Moore. Born: April 4, 1952 in Belfast, Northern Ireland and sadly died Feb. -

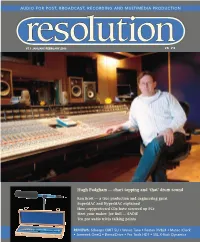

HUGH PADGHAM He Helped to Defi Ne the Sound of the 1980S—And Kept Right on Innovating by Howard Massey

JUNE 2010 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM PRODUCER Capitol Studios HUGH PADGHAM He helped to defi ne the sound of the 1980s—and kept right on innovating By Howard Massey IT WAS THE DRUM BREAK HEARD ’ROUND THE WORLD. Police. A couple of years later, the Police brought Padgham on Phil Collins’ 1981 debut solo single, “In the Air Tonight,” quietly board to co-produce their massive hit album Ghost in the Machine. simmered for a full three minutes and 40 seconds—then erupted From there, Padgham went on to helm albums by Paul McCartney, without warning into 10 thunderous notes on Collins’ tom-toms that David Bowie, Melissa Etheridge, Genesis and many other artists, air drummers have been joyously pounding out ever since. as well as several Sting solo albums. Along the way, he has won The enormous gated-reverb drum sound that would help to four Grammys in four different categories, including Producer of defi ne the sound of the 1980s was in large part the creation of the Year. Hugh Padgham (discovered while engineering Peter Gabriel’s third Padgham’s ultra-clean signature sound had a major impact album), and it loudly announced the arrival of a major production on the shift from the close-miked sounds of the ’70s to the open, talent. Padgham’s career had started at London’s Advision Studios, ambient sounds of the ’90s and beyond. “I often spend more time where he served as tea boy (the British equivalent to a runner). He pruning down than adding things,” he says. “Doing so can often moved to Lansdowne Studios in the mid-’70s and received formal require a musician to learn or evolve an altogether different part to training, quickly rising through the ranks to chief engineer. -

Recording Studio Design to Paul and Mum

Recording Studio Design To Paul and Mum. Janet Recording Studio Design Philip Newell Focal Press An imprint of Elsevier Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 200 Wheeler Road, Burlington MA 01803 First published 2003 Copyright © 2003, Philip Newell. All rights reserved The right of Philip Newell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science and Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK. Phone: (+44) (0) 1865 843830; fax: (+44) (0) 1865 853333; e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (www.elsevier.com), by selecting ‘Customer Support’ and then ‘Obtaining Permissions’ British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Newell, Philip Richard Recording studio design 1. Sound studios – Design 2. Acoustical engineering I. Title 621.3′823 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Newell, Philip Richard Recording studio design / Philip Newell. -

Electronic Voice

electronic voice STUDIO TECHNIQUES ~$90 ~$150 ~$600 ~$1300 ~$9000 dynamic mics magnetic transducer - essentially the design of a speaker, in reverse generally heaviest & most robust, making them ideal live mics polar pattern is frequently cardioid condenser mics electric transducer - thin membrane over a solid metal backplate (capacitor) requires external power typically the most sensitive, best frequency response, less noisy frequently come with switchable polar patterns ribbon mics electromagnetic transducer (a very thin, corrugated strip of metal) polar pattern is always bidirectional universally lower output compared to other mics high velocity sound pressure waves can cause the ribbon to stretch, break, or snap The Strokes - Is This It $3200 $400 ~$50 Phil Collins - In the Air Tonight single from Face Value, 1981 co-produced with Hugh Padgham in the Townhouse Studios, West London interview covering the production: https://www.mixonline.com/recording/cl assic-tracks-phil-collins-air-tonight-365 521 can you feel it? Alabama Shakes - Gimme All Your Love single from Sound and Color, 2015 produced by Blake Mills at Sound Emporium Studios in Nashville interview covering the production: https://www.soundonsound.com/people /inside-track-alabama-shakes-sound-co lor PITCH CORRECTION Cher - Believe Laurie Anderson - O Superman Symphony of Science - A Glorious Dawn SOUND VS MEANING Paul Botelho - rising inspired by and dedicated to the composer’s mentor Steven Miller, who was struggling with ALS István Márta - Doom. A sigh based on two songs the composer recorded during a visit to Romania; one of a woman’s long-dead parents, the other of the scene of a bloody battle Scott Wyatt - ...and nature is alone narrative written and recorded by a woman who grew up in Chernobyl originally for 8.1 surround. -

Rock Candy Magazine

MOSCOW MUSIC PEACE FESTIVAL STRICTLY OLD SCHOOL BADGES MÖTLEY CRÜE’S LAME CANCELLATION EXCUSE OLD SCHOOL BADGES MÖTLEY CRÜE’S LAME CANCELLATION STRICTLY FESTIVAL MUSIC PEACE MOSCOW COLLECTORS REMASTERED ISSUE EDITIONS & RELOADED 2 OUT NOW June–July 2017 £9.99 HARD, SWEET & STICKY LILLIAN AXE - ‘S/T’ LILLIAN AXE - ‘LOVE+WAR’ WARRANT - ‘CHERRY PIE’ WARRANT - ‘DIRTY ROTTEN FILTHY MOTHER’S FINEST - ‘IRON AGE’ STINKING RICH’ ROCK CANDY MAG ISSUE 2 JUNE – JULY 2017 ISSUE 2 JUNE – JULY MAG CANDY ROCK MAHOGANY RUSH - ‘LIVE’ FRANK MARINO - ‘WHAT’S NEXT’ FRANK MARINO FRANK MARINO - ‘JUGGERNAUT’ CREED - ‘S/T’ SURVIVOR ‘THE POWER OF ROCK AND ROLL’ ‘EYE OF THE TIGER’ KING KOBRA - ‘READY TO STRIKE’ KING KOBRA 707 - ‘S/T’ 707 - ‘THE SECOND ALBUM’ 707 - ‘MEGAFORCE’ OUTLAWS - ‘PLAYIN’ TO WIN’ ‘THRILL OF A LIFETIME’ “IT WAS LOUD – LIKE A FACTORY!” LOUD “IT WAS SAMMY HAGAR SALTY DOG TYKETTO - ‘DON’T COME EASY’ KICK AXE - ‘VICES’ KICK AXE KICK AXE - ‘ROCK THE WORLD’ ‘ALL NIGHT LONG’ ‘EVERY DOG HAS IT’S DAY’ ‘WELCOME TO THE CLUB’ NYMPHS -’S/T’ RTZ - ‘RETURN TO ZERO’ WARTHCHILD AMERICA GIRL - ‘SHEER GREED’ GIRL - ‘WASTED YOUTH’ LOVE/HATE ‘CLIMBIN’ THE WALLS’ ‘BLACKOUT IN THE RED ROOM’ MAIDEN ‘84 BEHIND THE SCENES ON THE LEGENDARY POLAND TOUR TARGET - ‘S/T’ TARGET - ‘CAPTURED’ MAYDAY - ‘S/T’ MAYDAY - ‘REVENGE’ BAD BOY - ‘THE BAND THAT BAD BOY - ‘BACK TO BACK’ MILWAUKEE MADE FAMOUS’ COMING SOON BAD ENGLISH - ‘S/T’ JETBOY - ‘FEEL THE SHAKE’ DOKKEN STONE FURY ALANNAH MILES - ‘S/T’ ‘BEAST FROM THE EAST’ ‘BURNS LIKE A STAR’ www.rockcandyrecords.com / [email protected] -

Bx Townhouse Buss Compressor Plugin Manual

bx_townhouse Buss Compressor Plugin Manual Developed by Brainworx and distributed by Plugin Alliance 1 Built in 1978 by the Townhouse maintenance staff from components supplied by Solid State Logic, this is the first outboard SSL bus compressor ever built. The Townhouse Compressor was designed and built to replicate the master buss compressor in an SSL 4000 B console. In 1978, shortly after taking delivery of their new SSL 4000 B Series console, the staff of The Townhouse made a request to Colin Sanders, the founder of Solid State Logic, to buy a standalone version of their console‘s centre section compressor. SSL didn‘t sell a standalone version at this point (and wouldn‘t for another 10 years) so a deal was struck whereby the studio could buy the circuit boards and individual components. These parts in conjunction with drawings and schematics were used to build the much loved Townhouse buss compressor. Not included in the purchase from SSL were the power supply and chassis; these were bought separately from RS (Radiospares). The input meter is also non-standard, this was not part of the original design and was added by the Townhouse staff. The Townhouse buss compressor, along with other similar processors made by the maintenance staff, were collectively known as the ‚Townhouse Toys‘. 2 The Townhouse Studios underwent many changes over the years with equipment upgrades and also alterations to room design and layout. SSL consoles including the 4000, 6000, 8000 & 9000 series were used at various times, however one detail remained consistent: the Townhouse Compressor in Studio 1. -

BLM16 NH Landscape 7 THM 4Pp X.Indd

Townhouse Mews, Goldhawk Road SHEPHERDS BUSH W12 With a wealth of unique creative energy, this landmark areas and spectacular bathroom suites and the houses TOWNHOUSE MEWS address has been remastered to create cutting-edge have the additional advantage of multiple outdoor areas collection of mews houses that have been beautifully including some beautiful private roof terraces accessible Shepherds Bush W12 arranged around a central glass courtyard, allowing natural via remotely operated glass roof lights. A stunning collection of contemporary houses set on the site of the historic and celebrated Townhouse light to flow into the homes, creating harmonious spaces Goldhawk Road is a well-known and highly sought- Recording Studios, boasting a fine location in the heart of vibrant Shepherds Bush. that represent the ultimate in contemporary living. after part of Shepherds Bush, close to Central London, Defined as one of the most famous recording studios in the world, Townhouse was created by Richard The architectural features throughout have resulted in providing an extensive array of exciting restaurants and Branson in 1978 and enjoyed subsequent ownership by the iconic creative labels EMI and Sanctuary clever and thoughtful living areas with unique elements bars, easy access to Chiswick and the River Thames and Records. Artists that recorded at Townhouse Studios included Queen, Phil Collins, The Jam, Coldplay, Duran Duran, Robbie Williams and Sir Elton John with Candle in the Wind, the fastest selling single of all and appeal to each floor. Vaulted ceilings, double height a short walk from the outstanding Westfield Shopping time being created within its walls and the renowned ‘Stone Room’ making use of its hallowed wall when atriums and private courtyards. -

Townhouse Mews

TOWNHOUSE MEWS WWW.TOWNHOUSEMEWS.COM HISTORY OF TOWNHOUSE STUDIOS The Town House one of the most famous studios in the world. Built by Richard Branson in 1978, and managed by Barbara Jeffries as part of the Virgin Studios Group. The Virgin Studios Group was acquired by EMI when Richard sold Virgin Records to EMI in 1992. The Sanctuary Group bought the studio from EMI in 2002. Al Stone, a recording engineer and producer, who trained at The Town House, ran the studios for Sanctuary in 2006, only to see Universal close it around April 2008 after a Sanctuary buy-out. The building had three recording rooms and had state of the art production facilities, for the time. Artists that recorded at Townhouse Studios included Elton John, Queen, Phil Collins, The Jam, Asia, Bryan Ferry, Coldplay, Muse, Duran Duran, Jamiroquai, Kylie Minogue, Oasis, XTC, Robbie Williams and Joan Armatrading. 1 TOWNHOUSE MEWS WWW.TOWNHOUSEMEWS.COM PERFECTLY IMPERFECT ENVIRONMENT The area is a hub for foodies and culture vultures. Dotted around Shepherd’s Bush Green and down numerous side streets, you will find great value restaurants, delicatessens, artisan bakeries, cafes, flower stalls and trendy gastro-pubs serving a diverse community of professionals, families and hungry shoppers. 3 TOWNHOUSE MEWS WWW.TOWNHOUSEMEWS.COM N Shepherd’s Bush market 5 min walk Shepherd’s Bush Green 5 min walk Notting Hill 10 min by car Goldhawk Road Underground Station 5 min walk Westfield Shopping Centre 10 min walk Paddington station 12 min by tube Hyde Park 15 min by car T OWNHOUSE Knightsbridge 15 min by car MEWS Sloane square 20 min by tube Soho 20 min by tube Heathrow airport 20 min by car Chelsea 20 min by car Oxford Street 25 min by car Mayfair 25 min by car The city of London 30 min by tube Covent Garden 40 min by tube Canary Wharf 45 min by tube S 5 TOWNHOUSE MEWS WWW.TOWNHOUSEMEWS.COM Above Above Shepherd’s Bush Empire, Bush Hall, Revens Court Park, Westfield centre Ravenscourt Park and the local area and one of many nearby eateries. -

Resolution Jan Feb 06 V5.1.Indd

AUDIO FOR POST, BROADCAST, RECORDING AND MULTIMEDIA PRODUCTION V5.1 JANUARY/FEBRUARYJANUARY/FEBRUARY 2006 Hugh Padgham — chart topping and ‘that’ drum sound Ken Scott — a true production and engineering great SuperMAC and HyperMAC explained How copyprotected CDs have screwed up PCs Meet your maker: Joe Bull — SADiE Ten pro audio trivia talking points REVIEWS: Schoeps CMIT 5U • Waves Tune • Fostex DV824 • Mutec iClock • Joemeek OneQ • BonsaiDrive • Pro Tools HD7 • SSL X-Rack Dynamics ��������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������������������� ����������� ���������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������� ��������������������������������������� ��������������� -

Kensington Record Labels

kensington record labels THE KENSINGTON RECORD LABEL CLUSTER Much focus has been made recently on ‘the silicon of the West End. roundabout’ around Old Street EC2, in terms of the cluster of Since 2008, following mergers and acquisitions, the six major technology companies in that area, but perhaps one of the record labels of the 1980s and 1990s have been reduced to most concentrated industries in London are the major record four ‘major labels’. labels. Following Universal Music Groups relocation of all All of these 4 ‘majors’ are now just off Kensington High Street subsidiary labels such as Polygram and Decca Records this. within no more than a mile of each other. year, all the major record labels are now in Kensington, west WARNER MUSIC SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 1 28 Kensington Church 2 9 Derry Street, W8 5HY Street, W8 4EP EMI UNIVERSAL MUSIC GROUP 3 27 Wrights Lane, 4 364 Kensington High Street, W14 8NS and W8 5SW Beaumont House Kensington Village, W14 8TS Also, the UK’s biggest live music and ticketing company, Live Nation, relocated in 2011 to the Chrysalis former HQ, The Phoenix Brewery, Notting Dale, W10 6SP in Kensington & Chelsea. HISTORY OF RECORD LABELS IN KENSINGTON & CHELSEA AND HAMMERSMITH & FULHAM POLYGRAM, 1 Sussex Place, Hammersmith (sold to Notting Hill Housing in 20011 as their HQ) ISLAND RECORDS, 22 St Peter’s Square, Hammersmith (sold and now occupied by niche west of West End agents, Frost Meadowcroft and architects, Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands) Photo by Iain Crockart POLYDOR, 72 Black Lion Lane, Hammersmith, W6 9BE Prior to relocating to Kensington High Street record the labels (converted to housing in 2008) have always been based in West London.