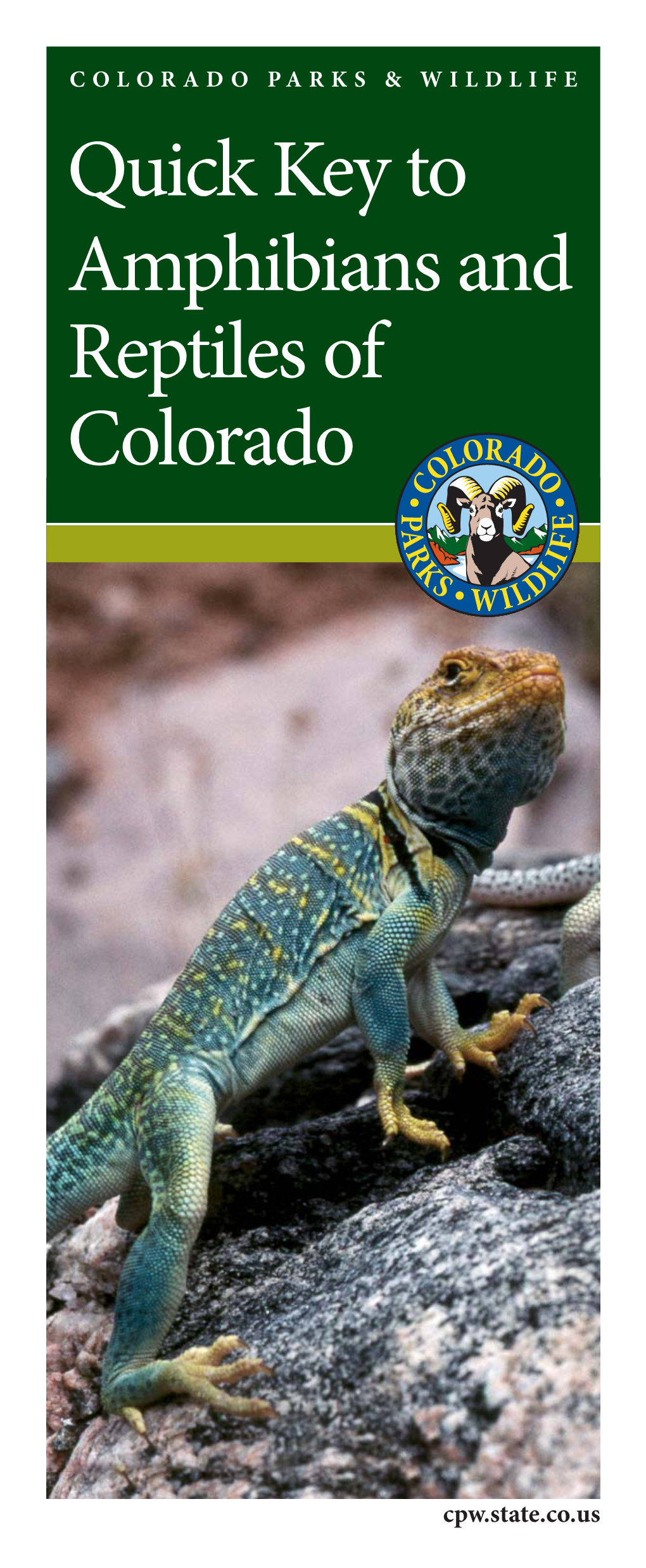

Quick Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of Colorado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New State Record for Aguascalientes, Mexico: Phrynosoma Cornutum (Squamata: Phrynosomatidae), the Texas Horned Lizard

Herpetology Notes, volume 7: 551-553 (2014) (published online on 3 October 2014) A new state record for Aguascalientes, Mexico: Phrynosoma cornutum (Squamata: Phrynosomatidae), the Texas horned lizard José Carlos Arenas-Monroy1*, Uri Omar García-Vázquez1, Rubén Alonso Carbajal-Márquez2 and Armando Cardona-Arceo3 Horned lizards of the genus Phrynosoma are widely most are typical of the Chihuahuan desert herpetofauna distributed through North America and range from (Morafka, 1977); some of these species have only southern Canada to western Guatemala (Sherbrooke, recently been documented (e.g. Quintero-Díaz et al., 2003). The genus comprises 17 species (Leaché and 2008; Sigala-Rodríguez et al., 2008; Sigala-Rodríguez McGuire, 2006; Nieto-Montes de Oca et al., 2014) and Greene, 2009). However, these arid plains still that exhibit exceptional morphological, ecological, remain relatively unexplored, because the majority and behavioral adaptations to arid environments of sampling efforts have focused on the canyons, (Sherbrooke, 1990, 2003). mountains, and sierras on the western half of the state Of these, Phrynosoma cornutum (Harlan, 1825) (Vázquez-Díaz and Quintero-Díaz, 2005). Here, we inhabits grasslands and scrublands from central United document the first records of Phrynosoma cornutum States southward to the Mexican states of Chihuahua, from the state of Aguascalientes. Coahuila, Durango, Nuevo León, San Luis Potosí, During a field trip on 16 July 2008, UOGV collected a Sonora, Tamaulipas, and Zacatecas from sea level up to male Phrynosoma cornutum ca. 4.7 km S of San Jacinto, 1830 m above sea level (m asl); this species has one of Rincón de Romos (22.304219°N, 102.238156°W; the largest ranges in the genus (Price, 1990). -

Sunshine Is Delicious, Rain Is Refreshing, Wind Braces Us Up, Snow Is Exhilarating; There Is Really No Such Thing As Bad Weather

3/14/11 The Midden Photo by Nathan Veatch Galveston Bay Area Chapter - Texas Master Naturalists April 2011 Table of Contents AT/Stewardship/Ed 2 Spring is Here by Diane Humes, President 2011 Outreach Opportunities Prairie Ponderings 3 Sunshine is delicious, rain is refreshing, wind braces us up, snow is exhilarating; there Wetland Wanderings 4 is really no such thing as bad weather, only different kinds of good weather. - John Ruskin Spring 2011 Class 6 Fishy Facts 7 We have had all kinds of good weather this winter, threat of ice, snow, and sleet unfortunately causing our first-ever chapter meeting cancellation in February. “Heartbreak” Turtles 7 Fortunately, we all stayed warm, dry, and safe. Our speaker, Chris LaChance, has re- Hook ‘em Horns 9 scheduled her presentation for the June meeting, so all is now well. We look forward Horny Toads 10 to all different kinds of good weather and good times for the coming year! FoGISP Training 11 The new chapter training class began February 17 and Raptor Workshop 12 continues most Thursdays into May. Check the schedule and please drop by to meet the 22 future Guppies from Julie 13 Galveston Bay Area Master Naturalists and welcome Red Harvester Ants 14 them to our mission of preservation, restoration, and education about our natural environment. The new class members bring a wealth of experience and love of nature, most citing experiences camping and exploring the outdoors since childhood. They are already into the food, fun, and friendship! The year 2011 marks our chapter’s 10th anniversary and plans are being formulated for a year of celebration. -

1 1. Species: Mountain Plover (Charadrius Montanus) 2. Status

1. Species: Mountain Plover (Charadrius montanus) 2. Status: Table 1 summarizes the current status of this species or subspecies by various ranking entity and defines the meaning of the status. Table 1. Current status of Charadrius montanus Entity Status Status Definition NatureServe G3 Species is Vulnerable At moderate risk of extinction or elimination due to a fairly restricted range, relatively few populations or occurrences, recent and widespread declines, threats, or other factors. CNHP S2B Species is Imperiled At high risk of extinction or elimination due to restricted range, few populations or occurrences, steep declines, severe threats, or other factors. (B=Breeding) Colorado SGCN, Tier 1 Species of Greatest Conservation Need State List Status USDA Forest R2 Sensitive Region 2 Regional Forester’s Sensitive Species Service USDI FWSb BoCC Included in the USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern list a Colorado Natural Heritage Program. b US Department of Interior Fish and Wildlife Service. The 2012 U.S. Forest Service Planning Rule defines Species of Conservation Concern (SCC) as “a species, other than federally recognized threatened, endangered, proposed, or candidate species, that is known to occur in the plan area and for which the regional forester has determined that the best available scientific information indicates substantial concern about the species' capability to persist over the long-term in the plan area” (36 CFR 219.9). This overview was developed to summarize information relating to this species’ consideration to be listed as a SCC on the Rio Grande National Forest, and to aid in the development of plan components and monitoring objectives. 3. Taxonomy Genus/species Charadrius montanus is accepted as valid (ITIS 2015). -

PEAK to PRAIRIE: BOTANICAL LANDSCAPES of the PIKES PEAK REGION Tass Kelso Dept of Biology Colorado College 2012

!"#$%&'%!(#)()"*%+'&#,)-#.%.#,/0-#!"0%'1%&2"%!)$"0% !"#$%("3)',% &455%$6758% /69:%8;%+<878=>% -878?4@8%-8776=6% ABCA% Kelso-Peak to Prairie Biodiversity and Place: Landscape’s Coat of Many Colors Mountain peaks often capture our imaginations, spark our instincts to explore and conquer, or heighten our artistic senses. Mt. Olympus, mythological home of the Greek gods, Yosemite’s Half Dome, the ever-classic Matterhorn, Alaska’s Denali, and Colorado’s Pikes Peak all share the quality of compelling attraction that a charismatic alpine profile evokes. At the base of our peak along the confluence of two small, nondescript streams, Native Americans gathered thousands of years ago. Explorers, immigrants, city-visionaries and fortune-seekers arrived successively, all shaping in turn the region and communities that today spread from the flanks of Pikes Peak. From any vantage point along the Interstate 25 corridor, the Colorado plains, or the Arkansas River Valley escarpments, Pikes Peak looms as the dominant feature of a diverse “bioregion”, a geographical area with a distinct flora and fauna, that stretches from alpine tundra to desert grasslands. “Biodiversity” is shorthand for biological diversity: a term covering a broad array of contexts from the genetics of individual organisms to ecosystem interactions. The news tells us daily of ongoing threats from the loss of biodiversity on global and regional levels as humans extend their influence across the face of the earth and into its sustaining processes. On a regional level, biologists look for measures of biodiversity, celebrate when they find sites where those measures are high and mourn when they diminish; conservation organizations and in some cases, legal statutes, try to protect biodiversity, and communities often struggle to balance human needs for social infrastructure with desirable elements of the natural landscape. -

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE Sceloporus Poinsettii

856.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE Sceloporus poinsettii Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Webb, R.G. 2008. Sceloporus poinsettii. Sceloporus poinsettii Baird and Girard Crevice Spiny Lizard Sceloporus poinsettii Baird and Girard 1852:126. Type-locality, “Rio San Pedro of the Rio Grande del Norte, and the province of Sonora,” restricted to either the southern part of the Big Burro Moun- tains or the vicinity of Santa Rita, Grant County, New Mexico by Webb (1988). Lectotype, National Figure 1. Adult male Sceloporus poinsettii poinsettii (UTEP Museum of Natural History (USNM) 2952 (subse- 8714) from the Magdalena Mountains, Socorro County, quently recataloged as USNM 292580), adult New Mexico (photo by author). male, collected by John H. Clark in company with Col. James D. Graham during his tenure with the U.S.-Mexican Boundary Commission in late Au- gust 1851 (examined by author). See Remarks. Sceloporus poinsetii: Duméril 1858:547. Lapsus. Tropidolepis poinsetti: Dugès 1869:143. Invalid emendation (see Remarks). Sceloporus torquatus Var. C.: Bocourt 1874:173. Sceloporus poinsetti: Yarrow “1882"[1883]:58. Invalid emendation. S.[celoporus] t.[orquatus] poinsettii: Cope 1885:402. Seloporus poinsettiii: Herrick, Terry, and Herrick 1899:123. Lapsus. Sceloporus torquatus poinsetti: Brown 1903:546. Sceloporus poissetti: Král 1969:187. Lapsus. Figure 2. Adult female Sceloporus poinsettii axtelli (UTEP S.[celoporus] poinssetti: Méndez-De la Cruz and Gu- 11510) from Alamo Mountain (Cornudas Mountains), tiérrez-Mayén 1991:2. Lapsus. Otero County, New Mexico (photo by author). Scelophorus poinsettii: Cloud, Mallouf, Mercado-Al- linger, Hoyt, Kenmotsu, Sanchez, and Madrid 1994:119. Lapsus. Sceloporus poinsetti aureolus: Auth, Smith, Brown, and Lintz 2000:72. -

Preliminary Data on the Age Structure of Phrynocephalus Horvathi in Mount Ararat (Northeastern Anatolia, Turkey)

BIHAREAN BIOLOGIST 6 (2): pp.112-115 ©Biharean Biologist, Oradea, Romania, 2012 Article No.: 121117 http://biozoojournals.3x.ro/bihbiol/index.html Preliminary data on the age structure of Phrynocephalus horvathi in Mount Ararat (Northeastern Anatolia, Turkey) Kerim ÇIÇEK1,*, Meltem KUMAŞ1, Dinçer AYAZ1 and C. Varol TOK2 1. Ege University, Faculty of Science, Biology Department, Zoology Section, Bornova, Izmir, Turkey 2. Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Faculty of Science - Literature, Biology Department, Zoology Section, Terzioğlu Campus, Çanakkale/Turkey. *Corresponding author, K. Çiçek, E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] Received: 24. September 2012 / Accepted: 22. October 2012 / Available online: 23. October 2012 / Printed: December 2012 Abstract. In this study, the age structure, growth and longevity of 27 individuals (8 juveniles, 8 males and 11 females) from the Mount Ararat (Iğdır, Turkey) population of Phrynocephalus horvathi were examined with the method of skeletochronology. According to the obtained data, the median age was 3.5 (range= 2-5) for males and 4 (2-5) for females. Both sexes reach sexual maturity after their first hibernation, and no statistically significant difference in age composition was observed between the sexes. According to von Bertalanffy growth curves, asymptotic body length was calculated as 51.29 mm and growth coefficient k - 0.60. Key words: Skeletochronology, growth, longevity, Phrynocephalus horvathi, Northeastern Anatolia. Introduction were measured using dial calipers to the nearest 0.01 mm and re- corded. The genus Phrynocephalus is a core of the Palearctic desert Humerus bones were dissected from specimens, fixed in 70% al- cohol and then washed with distilled water. -

Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska? Louis A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Herpetology Papers in the Biological Sciences 1993 Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska? Louis A. Somma Florida State Collection of Arthropods, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Population Biology Commons Somma, Louis A., "Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska?" (1993). Papers in Herpetology. 11. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Herpetology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. @ o /' number , ,... :S:' .' ,. '. 1'1'13 Do Mono Li ••rel,. Occur ill 1!I! ..br .... l< .. ? by Louis A. Somma Department of- Zoology University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611 Amphisbaenids, or worm lizards, are a small enigmatic suborder of reptiles (containing 4 families; ca. 140 species) within the order Squamata, which include~ the more speciose lizards and snakes (Gans 1986). The name amphisbaenia is derived from the mythical Amphisbaena (Topsell 1608; Aldrovandi 1640), a two-headed beast (one head at each end), whose fantastical description may have been based, in part, upon actual observations of living worm lizards (Druce 1910). While most are limbless and worm-like in appearance, members of the family Bipedidae (containing the single genus Sipes) have two forelimbs located close to the head. This trait, and the lack of well-developed eyes, makes them look like two-legged worms. -

Denudation History and Internal Structure of the Front Range and Wet Mountains, Colorado, Based on Apatite-Fission-Track Thermoc

NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF GEOLOGY & MINERAL RESOURCES, BULLETIN 160, 2004 41 Denudation history and internal structure of the Front Range and Wet Mountains, Colorado, based on apatitefissiontrack thermochronology 1 2 1Department of Earth and Environmental Science, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, Socorro, NM 87801Shari A. Kelley and Charles E. Chapin 2New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, Socorro, NM 87801 Abstract An apatite fissiontrack (AFT) partial annealing zone (PAZ) that developed during Late Cretaceous time provides a structural datum for addressing questions concerning the timing and magnitude of denudation, as well as the structural style of Laramide deformation, in the Front Range and Wet Mountains of Colorado. AFT cooling ages are also used to estimate the magnitude and sense of dis placement across faults and to differentiate between exhumation and faultgenerated topography. AFT ages at low elevationX along the eastern margin of the southern Front Range between Golden and Colorado Springs are from 100 to 270 Ma, and the mean track lengths are short (10–12.5 µm). Old AFT ages (> 100 Ma) are also found along the western margin of the Front Range along the Elkhorn thrust fault. In contrast AFT ages of 45–75 Ma and relatively long mean track lengths (12.5–14 µm) are common in the interior of the range. The AFT ages generally decrease across northwesttrending faults toward the center of the range. The base of a fossil PAZ, which separates AFT cooling ages of 45– 70 Ma at low elevations from AFT ages > 100 Ma at higher elevations, is exposed on the south side of Pikes Peak, on Mt. -

Habitat Selection of the Desert Night Lizard (Xantusia Vigilis) on Mojave Yucca (Yucca Schidigera) in the Mojave Desert, California

Habitat selection of the desert night lizard (Xantusia vigilis) on Mojave yucca (Yucca schidigera) in the Mojave Desert, California Kirsten Boylan1, Robert Degen2, Carly Sanchez3, Krista Schmidt4, Chantal Sengsourinho5 University of California, San Diego1, University of California, Merced2, University of California, Santa Cruz3, University of California, Davis4 , University of California, San Diego5 ABSTRACT The Mojave Desert is a massive natural ecosystem that acts as a biodiversity hotspot for hundreds of different species. However, there has been little research into many of the organisms that comprise these ecosystems, one being the desert night lizard (Xantusia vigilis). Our study examined the relationship between the common X. vigilis and the Mojave yucca (Yucca schidigera). We investigated whether X. vigilis exhibits habitat preference for fallen Y. schidigera log microhabitats and what factors make certain log microhabitats more suitable for X. vigilis inhabitation. We found that X. vigilis preferred Y. schidigera logs that were larger in circumference and showed no preference for dead or live clonal stands of Y. schidigera. When invertebrates were present, X. vigilis was approximately 50% more likely to also be present. These results suggest that X. vigilis have preferences for different types of Y. schidigera logs and logs where invertebrates are present. These findings are important as they help in understanding one of the Mojave Desert’s most abundant reptile species and the ecosystems of the Mojave Desert as a whole. INTRODUCTION such as the Mojave Desert in California. Habitat selection is an important The Mojave Desert has extreme factor in the shaping of an ecosystem. temperature fluctuations, ranging from Where an animal chooses to live and below freezing to over 134.6 degrees forage can affect distributions of plants, Fahrenheit (Schoenherr 2017). -

BULLETIN Chicago Herpetological Society

BULLETIN of the Chicago Herpetological Society Volume 52, Number 5 May 2017 BULLETIN OF THE CHICAGO HERPETOLOGICAL SOCIETY Volume 52, Number 5 May 2017 A Herpetologist and a President: Raymond L. Ditmars and Theodore Roosevelt . Raymond J. Novotny 77 Notes on the Herpetofauna of Western Mexico 16: A New Food Item for the Striped Road Guarder, Conophis vittatus (W. C. H. Peters, 1860) . .Daniel Cruz-Sáenz, David Lazcano and Bryan Navarro-Velazquez 80 Some Unreported Trematodes from Wisconsin Leopard Frogs . Dreux J. Watermolen 85 What You Missed at the April Meeting . .John Archer 86 Gung-ho for GOMO . Roger A. Repp 89 Herpetology 2017......................................................... 93 Advertisements . 95 New CHS Members This Month . 95 Minutes of the April 14 Board Meeting . 96 Show Schedule.......................................................... 96 Cover: The end of a battle between two Sonoran Desert Tortoises (Gopherus morafkai). Photograph by Roger A. Repp, Pima County, Arizona --- where the turtles are strong! STAFF Membership in the CHS includes a subscription to the monthly Bulletin. Annual dues are: Individual Membership, $25.00; Family Editor: Michael A. Dloogatch --- [email protected] Membership, $28.00; Sustaining Membership, $50.00; Contributing Membership, $100.00; Institutional Membership, $38.00. Remittance must be made in U.S. funds. Subscribers 2017 CHS Board of Directors outside the U.S. must add $12.00 for postage. Send membership dues or address changes to: Chicago Herpetological Society, President: Rich Crowley Membership Secretary, 2430 N. Cannon Drive, Chicago, IL 60614. Vice-president: Jessica Wadleigh Treasurer: Andy Malawy Manuscripts published in the Bulletin of the Chicago Herpeto- Recording Secretary: Gail Oomens logical Society are not peer reviewed. -

Dunes Sagebrush Lizard Habitat

TECHNICAL NOTES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE NEW MEXICO September, 2011 BIOLOGY TECHNICAL NOTE NO. 53 CRITERIA FOR BRUSH MANAGEMENT (314) in Lesser Prairie-Chicken and Dunes Sagebrush Lizard Habitat Introduction NRCS policy requires that when providing technical and financial assistance NRCS will recommend only conservation treatments that will avoid or minimize adverse effects, and to the extent practicable, provide long-term benefit to federal candidate species (General Manual 190 Part 410.22(E)(7)). This technical note provides the criteria to ensure that the NRCS practice of Brush Management (314) will avoid or minimize any adverse effects to two Candidate Species for Federal listing: the lesser prairie chicken Tympanuchus pallidicinctus (LEPC), and dunes sagebrush lizard Sceloporus arenicolus (DSL). Species Involved The lesser prairie chicken is a species of prairie grouse native to the southern high plains of the U.S.; including the sandhill rangelands of eastern New Mexico. The dunes sagebrush lizard is native only to a small area of southeastern New Mexico and west Texas, with a habitat range that overlaps the lesser prairie chicken range, but only occurs in the sand dune complexes associated with shinnery oak (Quercus havardii Rydb.). Both species’ habitat includes a component of brush: shinnery oak and/or sand sagebrush (Artemisia filifolia Torr.). See Appendix 1 and 2 for more details on each species. Geographic Area Covered by Technical Note No. 53 encompasses private and state lands within the range that supports the dunes sagebrush lizard and lesser prairie chicken habitat. This includes portions of seven counties in New Mexico: Chaves, Curry, De Baca, Eddy, Lea, Roosevelt, and Quay counties. -

Geochronology Database for Central Colorado

Geochronology Database for Central Colorado Data Series 489 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geochronology Database for Central Colorado By T.L. Klein, K.V. Evans, and E.H. DeWitt Data Series 489 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: T.L. Klein, K.V. Evans, and E.H. DeWitt, 2009, Geochronology database for central Colorado: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 489, 13 p. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................1