Programming in the Arts: an Impact Evaluation. INSTITUTION Far West Lab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIVE from LINCOLN CENTER December 31, 2002, 8:00 P.M. on PBS New York Philharmonic All-Gershwin New Year's Eve Concert

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER December 31, 2002, 8:00 p.m. on PBS New York Philharmonic All-Gershwin New Year's Eve Concert Lorin Maazel, an icon among present-day conductors, will make his long anticipated Live From Lincoln Center debut conducting the New York Philharmonic’s gala New Year’s Eve concert on Tuesday evening, December 31. Maazel began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s new Music Director in September, and already has put his stamp of authority on the playing of the orchestra. Indeed he and the Philharmonic were rapturously received wherever they performed on a recent tour of the Far East.Lorin Maazel, an icon among present-day conductors, will make his long anticipated Live From Lincoln Center debut conducting the New York Philharmonic’s gala New Year’s Eve concert on Tuesday evening, December 31. Maazel began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s new Music Director in September, and already has put his stamp of authority on the playing of the orchestra. Indeed he and the Philharmonic were rapturously received wherever they performed on a recent tour of the Far East. Celebrating the New Year with music is nothing new for Maazel: he holds the modern record for most appearances as conductor of the celebrated New Year’s Day concerts in Vienna by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. There, of course, the fare is made up mostly of music by the waltzing Johann Strauss family, father and sons. For his New Year’s Eve concert with the New York Philharmonic Maazel has chosen quintessentially American music by the composer considered by many to be America’s closest equivalent to the Strausses, George Gershwin. -

Ebook Download the Plays, Screenplays and Films of David

THE PLAYS, SCREENPLAYS AND FILMS OF DAVID MAMET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Steven Price | 192 pages | 01 Oct 2008 | MacMillan Education UK | 9780230555358 | English | London, United Kingdom The Plays, Screenplays and Films of David Mamet PDF Book It engages with his work in film as well as in the theatre, offering a synoptic overview of, and critical commentary on, the scholarly criticism of each play, screenplay or film. You get savvy industry tips and strategies for getting your screenplay noticed! Mamet is reluctant to be specific about Postman and the problems he had writing it, explaining. He shrugs off the whispers floating up and down the Great White Way about him selling out and going Hollywood. Contemporary playwright David Mamet's thought-provoking plays and screenplays such as Wag the Dog , Glengarry Glen Ross for which he won the Pulitzer Prize , and Oleanna have enjoyed popular and critical success in the past two decades. The Winslow Boy, Mamet's revisitation of Terence Rattigan's classic play, tells of a thirteen-year-old boy accused of stealing a five-shilling postal order and the tug of war for truth that ensues between his middle-class family and the Royal Navy. House of Games is a psychological thriller in which a young woman psychiatrist falls prey to an elaborate and ingenious con game by one of her patients who entraps her in a series of criminal escapades. Paul Newman plays Frank Calvin, an alcoholic and disgraced Boston lawyer who finds a shot at redemption with a malpractice case. I Just Kept Writing. The impressive number of essays , novels , screenplays , and films that Mamet has produced They might be composed and awesome on the battlefield, but there is a price, and that is their humanity. -

Radiowaves Will Be Featuring Stories About WPR and WPT's History of Innovation and Impact on Public Broadcasting Nationally

ON AIR & ONLINE FEBRUARY 2017 Final Forte WPR at 100 Meet Alex Hall Centennial Events Internships & Fellowships Featured Photo Earlier this month, WPR's To the Best of Our Knowledge explored the relationship between love WPR Next" Initiative Explores New Program Ideas and evolution at a sold- out live show in Madison, We often get asked, "Where does WPR come up with ideas for its sponsored by the Center programs?" First and foremost, we're inspired by you, our listeners for Humans in Nature. and neighbors around the state. During our 100th year, we're looking Excerpts from the show, to create the public radio programs of the future with a new initiative which included storyteller called WPR Next. Dasha Kelly Hamilton (pictured), will be We're going to try out a few new show ideas focused on science, broadcast nationally on pop culture, life in Wisconsin, and more. You can help our producers the show later this month. develop these ideas by telling us what interests you about these topics. Sound Bites Do you love science? What interests you most ---- do you wonder about new research in genetics, life on other planets, or ice cover on Winter Pledge Drive the Great Lakes? What about pop culture? What makes a great Begins February 21 book, movie or piece of music, and who would you like to hear WPR's winter interviewed? How about life in Wisconsin? What do you want to membership drive is know about our state's culture and history? What other topics would February 21 through 25. -

David Mamet - Edited by Christopher Bigsby Excerpt More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521894689 - The Cambridge Companion to David Mamet - Edited by Christopher Bigsby Excerpt More information 1 CHRISTOPHER BIGSBY David Mamet In 1974, a play set in part in a singles bar, laced with obscene language and charged with a seemingly frenetic energy, was voted Best Chicago Play. Transferred to Off Off and Off Broadway it picked up an Obie Award. Sexual Perversity in Chicago was not David Mamet’s first play, but it did mark the beginning of a career that would astonish in both its range and depth. The following year American Buffalo opened at Chicago’s Goodman The- atre in an “alternative season.” It was well received and opened on Broadway fifteen months later where it won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award. It ran for 135 performances, hardly a failure but in the hit or miss world of New York, not a copper-bottomed success either. Nonetheless, in three years he had announced his arrival in unequivocal terms. David Mamet came as something of a shock, not least because his first public success, Sexual Perversity in Chicago, seemed brutally direct in terms of its language and subject, as did American Buffalo. But it was already clear to many that here was a distinctive talent, albeit one that some critics found difficult to assess, not least because of his characters’ scatological language and fractured syntax, along with the apparent absence, in his plays, of a conventional plot. They praised what they took to be his linguistic naturalism, as though his intent had been to offer an insight into the cultural lower depths while capturing the precise rhythms of contemporary speech (though he did invoke Gorky’s The Lower Depths as being, like a number of his own plays, a study in stasis). -

Firstchoice Wusf

firstchoice wusf for information, education and entertainment • auGuSt 2010 Marvin Hamlisch Presents: The 70s, The Way We Were Renowned composer and conductor Marvin Hamlisch hosts and performs in this musical blast from the past. Three Dog Night, Debby Boone, Bobby Goldsboro, Peaches and Herb, Gloria Gaynor are a few of the musical greats who join him. The 1970s hit parade includes “You Light Up My Life,” “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head,” “Joy to the World,” and, of course, “The Way We Were.” Hamlisch fondly recalls the way we were in the 1970s. As he says in this special, “The country breathed a sigh of relief when the 1970s began. The new decade brought us peace, confidence and a feeling of national pride in our accomplishments. We had reached the stars we were aiming for; it’s a goal worth remembering today.” Airs Sunday, August 1, at 8 p.m., and Saturday, August 7, at 4 p.m. radio television WUSF 89.7 RADIO SCHEDULE AUGUST TV HIGHLIGHTS Monday through Friday Saturday continued Morning Edition ~ Classical Music 6-8 a.m. Carson Cooper 5-9 a.m. Weekend Edition 8-10 a.m. Classical Music ~ Car Talk 10-11 a.m. Russell Gant 9 a.m.-1 p.m. Wait Wait... Don’t Tell Me! 11-noon Classical Music ~ Classical Music noon-5 p.m. Bethany Cagle 1-4 p.m. All Things Considered 5-6 p.m. All Things Considered ~ Joshua Stewart A Prairie Home Companion 6-8 p.m. & Susan Giles Wantuck 4-6 p.m. This American Life 8-9 p.m. -

Classical Jazz

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER May 29, 2003, 8:00 p.m. on PBS Marsalis at the Penthouse In the summer of 1987 a "Classical Jazz" concert series was established at New York City's Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, under the inspired leadership of trumpet player, Wynton Marsalis. Seven years later this indispensable activity was redefined and became the autonomous jazz division at Lincoln Center--Jazz at Lincoln Center. Thus this essential American musical form took its place at Lincoln Center alongside such other constituents as the New York Philharmonic and the Metropolitan Opera, with Marsalis continuing as the driving force behind it. We have been privileged over the years on Live From Lincoln Center to be able to bring you several performances by this outstanding ensemble, most recently in concert with Kurt Masur and the New York Philharmonic. (Interestingly, during the years of the Masur family's residence in New York, the Maestro's son-- himself an aspiring conductor--became a great jazz enthusiast.) Our next Live From Lincoln Center telecast, on Thursday evening, May 29, will be devoted to yet another live performance by Jazz at Lincoln Center. But with a difference! Our previous sessions with Jazz at Lincoln Center have originated in one of the several concert halls in the Lincoln Center complex and have featured the artistry of the large ensemble. On May 29 the 90-minute performance will take place in the intimate confines of the Kaplan Penthouse high atop the building that houses Lincoln Center's administration offices. The Kaplan Penthouse has served as the locale for three previous Live From Lincoln Center telecasts: two featuring Itzhak Perlman, the other spotlighting Renée Fleming. -

December 2011: Primetime Alaskapublic.Org

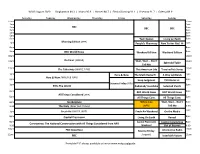

schedule available online: December 2011: Primetime alaskapublic.org 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:3010:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 Conversations: Bad Blood: A Cautionary Thu 12/1 This Old House Hour Charlie Rose Tavis Smiley Tavis Smiley Teen Suicide in Alaska Tale Washington Alaska PBS Arts From New York: Fri 12/2 Need to Know Charlie Rose Week Edition Great Performances Andrea Bocelli Live in Central Park Victor Borge Sat 12/3 Suze Orman's Money Class 60's Pop, Rock & Soul Victor Borge (start 6pm) Celtic Woman - Believe (start Sun 12/4 Lucille Ball: Finding Lucy An "American Masters" Special Rick Steves' European Christmas 6pm) Mon 12/5 Alone In The Wilderness, Part Two American Family: Anniversary Edition Charlie Rose Alaska Far Away: The New Deal Pioneers of the Matanuska Tue 12/6 Celtic Woman - Believe Charlie Rose Colony Wed 12/7 Suze Orman's Money Class Journey Of The Universe Victor Borge Charlie Rose 3 Steps To Incredible Health! With Joel Great Performances: Jackie How To Shop For Free With Thu 12/8 Charlie Rose Fuhrman, M.D. Evancho: Dream With Me In Concert Coupon Master Kathy Spencer Washington Alaska Human Nature Sings Motown With Special Fri 12/9 Need to Know Roy Orbison: In Dreams Charlie Rose Week Edition Guest Smokey Robinson Alaska Far Away Santana - Live At Montreux Sat 12/10 Alone In The Wilderness, Part Two Paul Simon: Live In Webster Hall, New York (start 6pm) 2011 Alone Great Performances: Jackie Sun 12/11 60's Pop, Rock & Soul Buddy Holly: Listen To Me (start 6pm) Evancho: Dream With Me In Concert Antiques Roadshow: B.E. -

Famous People from Michigan

APPENDIX E Famo[ People fom Michigan any nationally or internationally known people were born or have made Mtheir home in Michigan. BUSINESS AND PHILANTHROPY William Agee John F. Dodge Henry Joy John Jacob Astor Herbert H. Dow John Harvey Kellogg Anna Sutherland Bissell Max DuPre Will K. Kellogg Michael Blumenthal William C. Durant Charles Kettering William E. Boeing Georgia Emery Sebastian S. Kresge Walter Briggs John Fetzer Madeline LaFramboise David Dunbar Buick Frederic Fisher Henry M. Leland William Austin Burt Max Fisher Elijah McCoy Roy Chapin David Gerber Charles S. Mott Louis Chevrolet Edsel Ford Charles Nash Walter P. Chrysler Henry Ford Ransom E. Olds James Couzens Henry Ford II Charles W. Post Keith Crain Barry Gordy Alfred P. Sloan Henry Crapo Charles H. Hackley Peter Stroh William Crapo Joseph L. Hudson Alfred Taubman Mary Cunningham George M. Humphrey William E. Upjohn Harlow H. Curtice Lee Iacocca Jay Van Andel John DeLorean Mike Illitch Charles E. Wilson Richard DeVos Rick Inatome John Ziegler Horace E. Dodge Robert Ingersol ARTS AND LETTERS Mitch Albom Milton Brooks Marguerite Lofft DeAngeli Harriette Simpson Arnow Ken Burns Meindert DeJong W. H. Auden Semyon Bychkov John Dewey Liberty Hyde Bailey Alexander Calder Antal Dorati Ray Stannard Baker Will Carleton Alden Dow (pen: David Grayson) Jim Cash Sexton Ehrling L. Frank Baum (Charles) Bruce Catton Richard Ellmann Harry Bertoia Elizabeth Margaret Jack Epps, Jr. William Bolcom Chandler Edna Ferber Carrie Jacobs Bond Manny Crisostomo Phillip Fike Lilian Jackson Braun James Oliver Curwood 398 MICHIGAN IN BRIEF APPENDIX E: FAMOUS PEOPLE FROM MICHIGAN Marshall Fredericks Hugie Lee-Smith Carl M. -

Radio WSKG-WSQX Grid AUGUST 2020

WSKG August 2020 Binghamton 89.3 | Ithaca 90.9 | Hornell 88.7 | Elmira/Corning 91.1 | Oneonta 91.7 | Odessa 89.9 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 12am 12am 1am 1am BBC 2am BBC BBC 2am 3am 3am 4am 4am 5am 5am 6am Tech Nation Living on Earth 6am Morning Edition (NPR) 7am People's Pharmacy New Yorker Rad. Hr 7am 8am 8am 9am BBC World News Weekend Edition Weekend Edition 9am 10am 10am 11am On Point (WBUR) Wait, Wait... Don't 11am Splendid Table Tell Me 12pm 12pm The Takeaway (WNYC / PRI) This American Life Travel w/Rick Steves 1pm Here & Now The Moth Radio Hr A Way w/Words 1pm Here & Now (WBUR & NPR) 2pm Snap Judgment TED Radio Hr. 2pm 3pm Science Friday (PRI) 3pm PRI's The World RadioLab/ Invisibilia Selected Shorts 4pm BBC World News BBC World News 4pm All Things Considered (NPR) 5pm All Things Cons. All Things Cons. 5pm 6pm Marketplace White Lies Wait, Wait… Don't 6pm 6:30 The Daily (New York Times) (NPR) Tell Me 6:30 7pm 7pm Fresh Air (WHYY, NPR) Fresh Air Weekend On the Media 8pm Capitol Pressroom Living On Earth Reveal 8pm 9pm Capitol Pressroom Capitol Connection 9pm Coronavirus: The National Conversation with All Things Considered from NPR 9:30 Weekend Out of Bounds 9:30 10pm 10pm PBS NewsHour Science Friday Alternative Radio 11pm BBC (repeat) Interfaith Voices 11pm Printable PDF always available online at www.wskg.org/guide WSKG Classical August 2020 Binghamton 91.5 | Ithaca 92.1 | Corning 90.7 | Cooperstown 105.9 | Greene/Norwich 88.1 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 12am 12am Jazz -

Amahl and the Night Visitors

Set Design By: Steven C. Kemp AMAHL AND THE NIGHT VISITORS Welcome to Amahl and the Night Visitors! During this exceptional time, it has been a delight for us to bring you the gift of this wonderful holiday show. Created with love, we have brought together a variety of Kansas City’s talented artists to share this story of generosity and hope. It has been so heartwarming to see this production evolve, from the building of the scenery and puppets, to the addition of puppeteers, singers, and the orchestra. I know that it has meant a great deal to all involved to be in a safe space where creativity can flourish and all can practice their craft. The passion and joy of our performers, during this process, has been palpable. I wish you all a happy holiday and hope you enjoy this special show! Deborah Sandler, General Director and CEO BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2020-2021 OFFICERS Joanne Burns, President Tom Whittaker, Vice President Scott Blakesley, Secretary Craig L. Evans, Treasurer BOARD OF TRUSTEES Dr. Ivan Batlle Mira Mdivani Mark Benedict Edward P. Milbank Richard P. Bruening Steve Taylor Tom Butch Benjamin Mann, Counsel Melinda L. Estes, M.D. Karen Fenaroli Michael D. Fields Lafayette J. Ford, III Kenneth V. Hager Niles Jager Amy McAnarney EX-OFFICIO MEMBERS Andrew Garton | Chair, Orpheus KC Mary Leonida | President, Lyric Opera Circle Gigi Rose | Ball Chair, Lyric Opera Circle Dianne Schemm | President, Lyric Opera Guild Presents Amahl and the Night Visitors Opera in one act by Gian Carlo Menotti in order of PRINCIPAL CAST vocal appearance MOTHER Kelly Morel^ AMAHL Holly Ladage KING KASPAR Michael Wu KING MELCHIOR Daniel Belcher KING BALTHAZAR Scott Conner THE PAGE Keith Klein ^Former Resident Artist First Performance: NBC Opera Theatre, New York City, December 24, 1951. -

New Mexico Spanish Music New Mexico 2 AM 3 AM Spanish 3 AM 4 AM Music 4 AM Fresh Air 5 AM 5 AM Morning Edition Weekend 6 AM 6 AM 7 AM 7 AM

KIDS 88.1 FM GRANTS KGGA 88.1 FM GALLUP KEDP 91.1 FM LAS VEGAS KANR 91.9 FM SANTA ROSA PROGRAM SCHEDULE EFFECTIVE 10/26/2020 KANW 89.1 FM & HD1 ALBUQUERQUE Time Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Time 12 AM Saturday 12 AM Today’s Night 1 AM Hits Country 1 AM Classics 2 AM New Mexico Spanish Music New Mexico 2 AM 3 AM Spanish 3 AM 4 AM Music 4 AM Fresh Air 5 AM 5 AM Morning Edition Weekend 6 AM 6 AM 7 AM 7 AM 8 AM 8 AM On Point New Mexico Concerning Spanish Classical 9 AM The New Mexico TED Radio Music Music for a Splendid Radiolab Reveal 9 AM 9:30 Report from Hour Sunday Table AM Santa Fe Morning 10 AM Fresh Air 10 AM 11 AM 1A 11 AM Thistle & 12 PM 12 PM Shamrock 1 PM 1 PM 2 PM New Mexico 2 PM Sound Spanish 3 PM 3 PM Opinions Music 4 PM Live Wire 4 PM Wait 5 PM New Mexico Spanish Music Bullseye Wait…Don’t 5 PM Tell Me Wait All Things 6 PM Wait…Don’t 6 PM Considered Tell Me The New 7 PM Yorker 7 PM Radio Hour Native New Mexico The Moth 8 PM Music Spanish 8 PM Hours Music Radio Hour Snap 9 PM 9 PM Judgment Saturday Jazz Night 10 PM New Mexico 10 PM Today’s Night in America Spanish Hits Country Hearts of 11 PM Music 11 PM Classics Space KANW 89.1 HD2 ALBUQUERQUE K298BY 107.5 FM ALBUQUERQUE KANM 90.3 FM GRANTS kanw-2 PROGRAM SCHEDULE K216AW 91.1 FM GRANTS EFFECTIVE 2/1/2021 K216GQ 91.1 FM SANTA FE & LOS ALAMOS TIME MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY TIME 12 AM 12 AM 1 AM BBC World Service 1 AM 2 AM 2 AM BBC World Service 3 AM Morning Edition 3 AM 4 AM 4 AM 5 AM BBC World Service 5 AM 6 AM 6 AM 7 -

Stream on NEPM.Org

Stream on NEPM.org PROGRAM SCHEDULES NEPM New England Public Media presents locally-produced classical music seven days a week, jazz in the evenings and news from our award-winning local newsroom and NPR. Amherst / Springfield / Hartford ....................... WFCR 88.5 FM Lee ..........................................................................................98.3 FM North Adams ...................................................................... 101.1 FM Pittsfield / Lenox ...............................................................106.1 FM Great Barrington ................................................................. 98.7 FM Williamstown .......................................................................96.3 FM Weekday Saturday Sunday 5:00a.m. Morning Edition LOCAL NEWS 6:00a.m. Living on Earth 6:00a.m. Sunday Baroque 9:00a.m. Classical Music LOCAL 7:00a.m. Only a Game 8:00a.m. Weekend Edition Sunday 4:00p.m. All Things Considered LOCAL NEWS 8:00a.m. Weekend Edition Saturday 10:00a.m. Classical Music LOCAL 6:30p.m. Marketplace 11:00a.m. Wait Wait… Don’t Tell Me! 3:00p.m. From The Top 8:00p.m. Jazz à la Mode LOCAL 12:00p.m. Says You! 4:00p.m. This American Life 11:00p.m. Overnight Classical 1:00p.m. Saturday Opera 5:00p.m. All Things Considered 5:00p.m. All Things Considered 6:00p.m. American Routes 6:00p.m. Live From Here 8:00p.m. Tertulia LOCAL 8:00p.m. Jazz Safari LOCAL 10:00p.m. Latino USA 11:00p.m. Overnight Classical 11:00p.m. Overnight Classical NEPM News Network The NEPM News Network offers balanced reporting, in-depth interviews, call-in discussions, and fresh perspectives on the biggest stories from around the world, and here in western New England. Springfield / Amherst / Westfield WNNZ 640 AM Franklin County .........................................