Arxiv:2007.04491V3 [Math.AP] 24 Aug 2020 Hoe 1.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meetings & Conferences of the AMS, Volume 48, Number 11

mtgs.qxp 10/30/01 1:55 PM Page 1415 Meetings & Conferences of the AMS IMPORTANT INFORMATION REGARDING MEETINGS PROGRAMS: AMS Sectional Meeting programs do not appear in the print version of the Notices. However, comprehensive and continually updated meeting and program information with links to the abstract for each talk can be found on the AMS website. See http://www.ams.org/meetings/. Programs and abstracts will continue to be displayed on the AMS website in the Meetings and Conferences section until about three weeks after the meeting is over. Final programs for Sectional Meetings will be archived on the AMS website in an electronic issue of the Notices as noted below for each meeting. Groups and Covering Spaces in Algebraic Geometry, Michael Irvine, California Fried, University of California Irvine, and Helmut Voelklein, University of California Irvine University of Florida. Harmonic Analyses and Partial Differential Equations, November 10–11, 2001 Gustavo Ponce, University of California Santa Barbara, and Gigliola Staffilani, Brown University and Stanford Meeting #972 University. Western Section Harmonic Analysis and Complex Analysis, Xiaojun Huang, Associate secretary: Bernard Russo Rutgers University, and Song-Ying Li, University of Cali- Announcement issue of Notices: September 2001 fornia Irvine. Program first available on AMS website: September 27, Operator Spaces, Operator Algebras, and Applications, 2001 Marius Junge, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Program issue of electronic Notices: December 2001 and Timur Oikhberg, University of Texas and University Issue of Abstracts: Volume 22, Issue 4 of California Irvine. Deadlines Partial Differential Equations and Applications, Edriss S. Titi, For organizers: Expired University of California Irvine. -

Soliton Model

On long time dynamic and singularity formation of NLS MASSACHTS ITTUTE by OF TECHNOLOGY Chenjie Fan AUG 0 12017 B.S., Peking University (2012) LIBRARIES Submitted to the Department of Mathematics ARCHIVES in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2017 @ Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2017. All rights reserved. Signature redacted Author ............................................ Department of Mathematics May 3rd, 2017 Certified by. Signature redacted ... Gigliola Staffilani LAbby Rockefeller Mauze Professor Thesis Supervisor Accepted by... Signature redacted .................. William Minicozzi Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Theses 2 On long time dynamic and singularity formation of NLS by Chenjie Fan Submitted to the Department of Mathematics on May 3rd, 2017, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract In this thesis, we investigate the long time behavior of focusing mass critical nonlinear Schr6dinger equation (NLS). We will focus on the singularity formation and long time asymptotics. To be specific, there are two parts in the thesis. In the first part, we give a construction of log-log blow up solutions which blow up at m prescribed points simultaneously. In the second part, we show weak convergence to ground state for certain radial blow up solutions to NLS at well chosen time sequence. We also include a lecture note on concentration compactness. Concentration compactness is one of the main tool we use in the second part of the thesis. Thesis Supervisor: Gigliola Staffilani Title: Abby Rockefeller Mauze Professor 3 I Acknowledgments I am very fortunate to work with my advisor, Gigliola Staffilani. -

Meetings & Conferences of the AMS, Volume 49, Number 5

Meetings & Conferences of the AMS IMPORTANT INFORMATION REGARDING MEETINGS PROGRAMS: AMS Sectional Meeting programs do not appear in the print version of the Notices. However, comprehensive and continually updated meeting and program information with links to the abstract for each talk can be found on the AMS website.See http://www.ams.org/meetings/. Programs and abstracts will continue to be displayed on the AMS website in the Meetings and Conferences section until about three weeks after the meeting is over. Final programs for Sectional Meetings will be archived on the AMS website in an electronic issue of the Notices as noted below for each meeting. Niky Kamran, McGill University, Wave equations in Kerr Montréal, Quebec geometry. Rafael de la Llave, University of Texas at Austin, Title to Canada be announced. Centre de Recherches Mathématiques, Special Sessions Université de Montréal Asymptotics for Random Matrix Models and Their Appli- cations, Nicholas M. Ercolani, University of Arizona, and May 3–5, 2002 Kenneth T.-R. McLaughlin, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and University of Arizona. Meeting #976 Combinatorial Hopf Algebras, Marcelo Aguiar, Texas A&M Eastern Section University, and François Bergeron and Christophe Associate secretary: Lesley M. Sibner Reutenauer, Université du Québec á Montréal. Announcement issue of Notices: March 2002 Combinatorial and Geometric Group Theory, Olga G. Khar- Program first available on AMS website: March 21, 2002 lampovich, McGill University, Alexei Myasnikov and Program issue of electronic Notices: May 2002 Vladimir Shpilrain, City College, New York, and Daniel Issue of Abstracts: Volume 23, Issue 3 Wise, McGill University. Commutative Algebra and Algebraic Geometry, Irena Deadlines Peeva, Cornell University, and Hema Srinivasan, Univer- For organizers: Expired sity of Missouri-Columbia. -

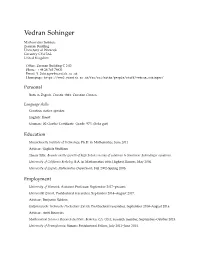

Vedran Sohinger

Vedran Sohinger Mathematics Institute Zeeman Building University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7AL United Kingdom Office: Zeeman Building C 2.02 Phone: + 44 24 765 74831 Email: [email protected] Homepage: https://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/maths/people/staff/vedran_sohinger/ Personal Born in Zagreb, Croatia 1983. Croatian Citizen. Language skills Croatian: native speaker. English: fluent. German: B2 Goethe Certificate. Grade: 97% (Sehr gut). Education Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ph.D. in Mathematics, June 2011. Advisor: Gigliola Staffilani. Thesis Title: Bounds on the growth of high Sobolev norms of solutions to Nonlinear Schrödinger equations. University of California Berkeley, B.A. in Mathematics with Highest Honors, May 2006. University of Zagreb, Mathematics Department, Fall 2002–Spring 2003. Employment University of Warwick, Assistant Professor, September 2017–present. Universität Zürich, Postdoctoral researcher, September 2016–August 2017. Advisor: Benjamin Schlein. Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich, Postdoctoral researcher, September 2014–August 2016. Advisor: Antti Knowles. Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, Berkeley, CA, USA, research member, September–October 2015. University of Pennsylvania, Simons Postdoctoral Fellow, July 2011–June 2014. Vedran Sohinger 2 Advisors: Philip Gressman and Robert Strain. Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in the Sciences, Leipzig, Germany, visitor, January–February 2012. Host: Felix Otto. Research interests Nonlinear Dispersive Equations, Harmonic Analysis, Quantum many-body problems. Publications Thesis Bounds on the growth of high Sobolev norms of solutions to nonlinear Schrödinger equations, Ph.D. Thesis, MIT (2011). Advisor: Gigliola Staffilani. Papers (13) A microscopic derivation of Gibbs measures for nonlinear Schrödinger equations with unbounded interaction potentials, preprint (2019), 77 pages, 5 figures. https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.08137. -

Curriculum Vitae GIGLIOLA STAFFILANI

Curriculum Vitae GIGLIOLA STAFFILANI Addresses 37 Dana Street Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02138 Department of Mathematics Phone: (617) 876-3225 room 2-246 Email: [email protected] 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 Phone: (617) 253-4981 Education 1990–1995 University of Chicago Ph.D. in Mathematics, June 1995 S.M. Mathematics, August 1991. 1985–1989 Universit´adi Bologna Laurea in Matematica, summa cum laude Academic Appointments 2007-2012 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abby Rockefeller Mauze Professor 2006-Present Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor 2002-2006 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Associate Professor 2003-2004 Princeton Member of the Institute for Advanced Study January-May, 2002 Harvard University Visiting Associate Professor 2001-2002 Brown University Associate Professor 2001-2002 Stanford University Associate Professor on leave 1999-2001 Stanford University Assistant Professor 1998-1999 Princeton University Assistant Professor 1996-1998 Stanford University Szeg¨oAssistant Professor 1995-1996 Princeton Member of the Institute for Advanced Study Fellowships and Teaching Awards NSF Grant 2006-2010 NSF Grant 2000-2003 Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship 2000-2002 NSF Grant 1998-2001 Terman Award 1998-2001 Borsa di Studio C.N.R. per l’estero, 1993-1995 University of Chicago fellowship, 1990-1995 Borsa di Studio INdAM 1989-1990 The Harold M. Bacon Memorial Teaching Award. Stanford University, 1997 The Lawrence and Josephine Graves Memorial Lectureship Award. University of Chicago, 1994 The Physical Sciences Teaching Prize University of Chicago, 1994. Professional Experience Co-organizer of the Clay Mathematics Institute 2008 Summer School on Evolution Equations Eidgen¨ossische Technische Hochschule, Z¨urich, Switzerland June 23 – July 18, 2008. -

Jean E. Rubin Memorial Lecture 10Th Annual Women in Mathematics

DepartmentDepartment of Mathematics of Mathematics 10th Annual Women in Mathematics Day Jean E. Rubin Memorial Lecture Tuesday, November 15, 2016 4:30 p.m. LWSN 1142 Refreshments will be served at 4:00 p.m. outside Lawson 1142 Recent developments on certain dispersive equations as infinite dimensional Hamiltonian systems. Abstract: The mathematical nature of dispersion is the starting point of a very rich mathematical activity that has seen incredible progress in the last twenty years, and that has involved many different branches of mathematics: Fourier and harmonic analysis, analytic number theory, differential and symplectic geometry, dynamical systems and probability. In this talk I will give examples of these diverse directions and related open problems. Speaker: Gigliola Staffilani Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of Mathematics Gigliola Staffilani was named the Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of Mathematics in 2007. She received the B.S. equivalent from the University of Bologna in 1989, and the S.M. and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Chicago in 1991 and 1995, respectively. Carlos Kenig was her doctoral advisor. Following a Szegö Assistant Professorship at Stanford, she had faculty appointments at Stanford, Princeton and Brown, before joining the MIT mathematics faculty in 2002. Professor Staffilani is an analyst, with a concentration on dispersive nonlinear PDEs. At Stanford, she received the Harold M. Bacon Memorial Teaching Award in 1997, and was given the Frederick E. Terman Award for young faculty in 1998. She was a Sloan fellow from 2000-02. In 2013 she was elected member of the Massachusetts Academy of Science and a fellow of the AMS, and in 2014 fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. -

Analysis & PDE Vol. 5 (2012)

ANALYSIS & PDE Volume 5 No. 4 2012 msp Analysis & PDE msp.berkeley.edu/apde EDITORS EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Maciej Zworski University of California Berkeley, USA BOARD OF EDITORS Michael Aizenman Princeton University, USA Nicolas Burq Université Paris-Sud 11, France [email protected] [email protected] Luis A. Caffarelli University of Texas, USA Sun-Yung Alice Chang Princeton University, USA [email protected] [email protected] Michael Christ University of California, Berkeley, USA Charles Fefferman Princeton University, USA [email protected] [email protected] Ursula Hamenstaedt Universität Bonn, Germany Nigel Higson Pennsylvania State Univesity, USA [email protected] [email protected] Vaughan Jones University of California, Berkeley, USA Herbert Koch Universität Bonn, Germany [email protected] [email protected] Izabella Laba University of British Columbia, Canada Gilles Lebeau Université de Nice Sophia Antipolis, France [email protected] [email protected] László Lempert Purdue University, USA Richard B. Melrose Massachussets Institute of Technology, USA [email protected] [email protected] Frank Merle Université de Cergy-Pontoise, France William Minicozzi II Johns Hopkins University, USA [email protected] [email protected] Werner Müller Universität Bonn, Germany Yuval Peres University of California, Berkeley, USA [email protected] [email protected] Gilles Pisier Texas A&M University, and Paris 6 Tristan Rivière ETH, Switzerland [email protected] [email protected] Igor Rodnianski Princeton University, USA Wilhelm Schlag University of Chicago, USA [email protected] [email protected] Sylvia Serfaty New York University, USA Yum-Tong Siu Harvard University, USA [email protected] [email protected] Terence Tao University of California, Los Angeles, USA Michael E. -

Letter from the Chair Celebrating the Lives of John and Alicia Nash

Spring 2016 Issue 5 Department of Mathematics Princeton University Letter From the Chair Celebrating the Lives of John and Alicia Nash We cannot look back on the past Returning from one of the crowning year without first commenting on achievements of a long and storied the tragic loss of John and Alicia career, John Forbes Nash, Jr. and Nash, who died in a car accident on his wife Alicia were killed in a car their way home from the airport last accident on May 23, 2015, shock- May. They were returning from ing the department, the University, Norway, where John Nash was and making headlines around the awarded the 2015 Abel Prize from world. the Norwegian Academy of Sci- ence and Letters. As a 1994 Nobel Nash came to Princeton as a gradu- Prize winner and a senior research ate student in 1948. His Ph.D. thesis, mathematician in our department “Non-cooperative games” (Annals for many years, Nash maintained a of Mathematics, Vol 54, No. 2, 286- steady presence in Fine Hall, and he 95) became a seminal work in the and Alicia are greatly missed. Their then-fledgling field of game theory, life and work was celebrated during and laid the path for his 1994 Nobel a special event in October. Memorial Prize in Economics. After finishing his Ph.D. in 1950, Nash This has been a very busy and pro- held positions at the Massachusetts ductive year for our department, and Institute of Technology and the In- we have happily hosted conferences stitute for Advanced Study, where 1950s Nash began to suffer from and workshops that have attracted the breadth of his work increased. -

Presentation of the Austrian Mathematical Society - E-Mail: [email protected] La Rochelle University Lasie, Avenue Michel Crépeau B

NEWSLETTER OF THE EUROPEAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Features S E European A Problem for the 21st/22nd Century M M Mathematical Euler, Stirling and Wallis E S Society History Grothendieck: The Myth of a Break December 2019 Issue 114 Society ISSN 1027-488X The Austrian Mathematical Society Yerevan, venue of the EMS Executive Committee Meeting New books published by the Individual members of the EMS, member S societies or societies with a reciprocity agree- E European ment (such as the American, Australian and M M Mathematical Canadian Mathematical Societies) are entitled to a discount of 20% on any book purchases, if E S Society ordered directly at the EMS Publishing House. Todd Fisher (Brigham Young University, Provo, USA) and Boris Hasselblatt (Tufts University, Medford, USA) Hyperbolic Flows (Zürich Lectures in Advanced Mathematics) ISBN 978-3-03719-200-9. 2019. 737 pages. Softcover. 17 x 24 cm. 78.00 Euro The origins of dynamical systems trace back to flows and differential equations, and this is a modern text and reference on dynamical systems in which continuous-time dynamics is primary. It addresses needs unmet by modern books on dynamical systems, which largely focus on discrete time. Students have lacked a useful introduction to flows, and researchers have difficulty finding references to cite for core results in the theory of flows. Even when these are known substantial diligence and consulta- tion with experts is often needed to find them. This book presents the theory of flows from the topological, smooth, and measurable points of view. The first part introduces the general topological and ergodic theory of flows, and the second part presents the core theory of hyperbolic flows as well as a range of recent developments. -

Global Well-Posedness for a Periodic Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation In

GLOBAL WELL-POSEDNESS FOR A PERIODIC NONLINEAR SCHRODINGER¨ EQUATION IN 1D AND 2D DANIELA DE SILVA, NATASAˇ PAVLOVIC,´ GIGLIOLA STAFFILANI, AND NIKOLAOS TZIRAKIS Abstract. The initial value problem for the L2 critical semilinear Schr¨odinger equation with periodic boundary data is considered. We show that the problem is globally well posed in H s(Td), for s>4/9 and s>2/3 in 1D and 2D respectively, confirming in 2D a statement of Bourgain in [3]. We use the “I-method”. This method allows one to introduce a modification of the energy functional that is well defined for initial data below the H 1(Td) threshold. The main ingredient in the proof is a “refinement” of the Strichartz’s estimates Td Rd Zd that hold true for solutions defined on the rescaled space, λ = /λ , d =1, 2. 1. Introduction In this paper we study the L2 critical Cauchy problem 4 d (1.1) iut +∆u −|u| d u =0,x∈ T ,t≥ 0 s d (1.2) u(x, 0) = u0(x) ∈ H (T ), where d =1, 2 and Td = Rd/Zd is the d-dimensional torus. We say that a Cauchy problem is locally well-posed in Hs if for any choice of initial s data u0 ∈ H , there exists a positive time T = T ($u0$Hs ) depending only on the norm of the initial data, such that a solution to the initial value problem exists on the time s 0 s interval [0,T], is unique and the solution map from Hx to Ct Hx depends continuously on the initial data on the time interval [0,T]. -

Contenido De La III Edición

Premio Fundaci6n Polar "Lorenzo Mendoza Fleury" . 1987 FUNDACION POLAR I l l Junta Directiva Presidenta: Leonor Gimenez de Mendoza Vice-Presidenta: Morella Pacheco de Pietri Directores: Pedro Berroeta Victor Gimenez Landfnez Alfredo Guinand Baldo Leopoldo Marquez Anez Orlando Perdomo Vicente Perez Davila Gustavo Roosen Carlos Eduardo Stoll< 3 Presentaci6n Nada perrnanente puede ser llevado a cabo sin una tenacidad vigilante, activa e incansable. Esa voluntad del esfuerzo continuo es la que irnpulsa tanto a los individuos corno a los pueblos y hace de ellos creadores de civilizaci6n y cultura. Porque nada se logra con la sola revelaci6n de lo nuevo. Nada del encuentro inesperado con la posible soluci6n del enigma. Nada del hallazgo de un camino distinto, sin la necesaria labor cotidiana y paciente que transforrna en realidad los sueftos. La gran fuerza de la Naturaleza es la constancia. De ella debernos aprender esa virtud para aplicarla en todos los carnpos de la actividad hurnana, ya que ninguna meta puede ser lograda sin antes haberla rnerecido. La tarea de aprender esa lecci6n sera larga y dificil, pero fructifera. A ella debernos consagramos todos. Hernos de dejar a un lado la improvisaci6n y el apresurarniento, el entusiasrno inicial que rapidarnente se esfurna y la tendencia a proponernos rnwtiples objetivos que luego desechamos por inalcanzables. Si querernos avanzar, si querernos que nuestro pueblo alcance el nivel que podria corresponderle en el campo de las ciencias, tenernos que crear en nuestra juventud el habito cientifico, que no es otra cosa sino la armoniosa conjunci6n de la observaci6n sisternatica, el juicio abierto a todas las hip6tesis, la intuici6n alerta y, sobre todo, un ritrno constante en el trabajo y la capacidad de esperar: porque µo hay ciencia sin paciencia. -

2008 Bôcher Prize

2008 Bôcher Prize The 2008 Maxime Bôcher Memorial Prize was hyperbolic conservation laws. Professor Bressan awarded at the 114th Annual Meeting of the AMS has made important contributions to the well- in San Diego in January 2008. posedness theory; the results have been sum- Established in 1923, the prize honors the mem- marized in his monograph Hyperbolic Systems of ory of Maxime Bôcher (1867–1918), who was the Conservation Laws. The One-Dimensional Cauchy Society’s second Colloquium Lecturer in 1896 and Problem (Oxford Lecture Series in Mathematics who served as AMS president during 1909–1910. and Its Applications, 20, Oxford University Press, Bôcher was also one of the founding editors of Oxford, 2000, xii + 250 pp.). Another landmark Transactions of the AMS. The original endowment achievement is the work on zero dissipation limit was contributed by members of the Society. The (with Stefano Bianchini), “Vanishing viscosity so- prize is awarded for a notable paper in analysis lutions of nonlinear hyperbolic systems”, Ann. of published during the preceding six years. To be Math. (2) 161 (2005), no. 1, 223–342. eligible, the author should be a member of the Biographical Sketch AMS or the paper should have been published in Alberto Bressan was born in Venice, Italy. He com- a recognized North American journal. The prize is pleted his undergraduate studies at the University given every three years and carries a cash award of Padova, Italy, and received a Ph.D. from the of US$5,000. University of Colorado, Boulder, in 1982. He has The Bôcher Prize is awarded by the AMS Coun- held faculty positions at the University of Colorado cil acting on the recommendation of a selection and at the International School for Advanced Stud- committee.