Specifically String Quartets—In Japan from 1989 to 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kronos Quartet Prelude to a Black Hole Beyond Zero: 1914-1918 Aleksandra Vrebalov, Composer Bill Morrison, Filmmaker

KRONOS QUARTET PRELUDE TO A BLACK HOLE BeyOND ZERO: 1914-1918 ALeksANDRA VREBALOV, COMPOSER BILL MORRISon, FILMMAKER Thu, Feb 12, 2015 • 7:30pm WWI Centenary ProJECT “KRONOs CONTINUEs With unDIMINISHED FEROCity to make unPRECEDENTED sTRING QUARtet hisTORY.” – Los Angeles Times 22 carolinaperformingarts.org // #CPA10 thu, feb 12 • 7:30pm KRONOS QUARTET David Harrington, violin Hank Dutt, viola John Sherba, violin Sunny Yang, cello PROGRAM Prelude to a Black Hole Eternal Memory to the Virtuous+ ....................................................................................Byzantine Chant arr. Aleksandra Vrebalov Three Pieces for String Quartet ...................................................................................... Igor Stravinsky Dance – Eccentric – Canticle (1882-1971) Last Kind Words+ .............................................................................................................Geeshie Wiley (ca. 1906-1939) arr. Jacob Garchik Evic Taksim+ ............................................................................................................. Tanburi Cemil Bey (1873-1916) arr. Stephen Prutsman Trois beaux oiseaux du Paradis+ ........................................................................................Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) arr. JJ Hollingsworth Smyrneiko Minore+ ............................................................................................................... Traditional arr. Jacob Garchik Six Bagatelles, Op. 9 ..................................................................................................... -

20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 665. - 2 - January 2021 ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 1 Adam, Claus: Vcl Con/ Barber: Die Natali - Kates vcl, cond.Mester 1975 S LOUISVILLE LS 745 A 12 2 Adams, John: Shaker Loops, Phrygian Gates - McCray pno, Ridge SQ, etc 1979 S 1750 ARCH S 1784 A 10 3 Baaren, Kees van: Musica per orchestra; Musica per organo/Brons, Carel: Prisms DONEMUS 72732 A 8 (organ) - Wolff organ, cond.Haitink , (score enclosed) S 4 Badings: Con for Orch/H.Andriessen: Kuhnau Var/Brahms: Sym 4 - Regionaal 2 x REGIONAAL JBTG A 15 Jeugd Orkest, cond.Sevenhuijsen live, 1982, 1984 S 7118401 5 Bax: Sym 3, The Happy Forest - London SO, cond.Downes (UK) (p.1969) S RCA SB 6806 A 8 6 Bernstein, Elmer: Summer and Smoke (sound track) - cond.comp S ENTRACTE ERS 6519 A 8 7 Bernstein, Elmer: The Magnificent Seven - cond.comp S LIBERTY EG 260581 A 8 8 Bernstein, Elmer: To Kill a Mockingbird (film music) - Royal PO, cond.E.Bernstein FILMMUSIC FMC 7 A 25 1976 S 9 Bernstein, Elmer: Walk on the Wild Side (soundtrack) - cond.comp S CHOREO AS 4 A 8 10 Bernstein, Ermler: Paris Swings (soundtrack) S CAPITOL ST 1288 A 8 11 Bolling: The Awakening (soundtrack) S ENTRACTE ERS 6520 A 8 12 Bretan, Nicolae: Ady Lieder - comp.pno & vocal (one song only), L.Konya bar, MHS 3779 A 8 F.Weiss, M.Berkofsky pno S 13 Castelnuovo-Tedesco: The Well-Tempered Guitars - Batendo Guitar Duo (gatefold) 2 x ETCETERA ETC 2009 A 15 (p.1986) S 14 Casterede, Jacques: Suite a danser - Hewitt Orch (light music) 10" DISCOPHILE SD 5 B+ 10 15 Dandara, Liviu: Timpul Suspendat, Affectus, Quadriforium III -

School Ofmusic

' . .. CHAMBER MUSIC CONCERT ( ~ ...... LEONE BUYSE,flute ~ .- MICHAEL WEBSTER, clarinet ., r BRIAN CONNELLY, piano - . KENNETH GOLDSMITH, violin ~ ROBERT BROPHY, v·iola - .J RICHARD BELCHER, cello ,..,. _,. ' Friday, February 6, 2004 8:00 p.m . • l Lillian H. Duncan Recital Hall ·1 RICE UNIVERSITY School~ - ' ofMusic 1 - ' • - PROGRAM • • Duet in G Major for Carl Philippe Emmanuel Bach Flute and Violin (1714-1788) Andante Allegro • 1 Allegretto ' .. ' I - ,_I Quartet for Clarinet and Strings Johan Nepomuk Hummel Allegro moderato (1778-1837) La Seccatura ("The Nuisance"): Allegro molto Andante Rondo: Allegretto INTERMISSION Sonata for Flute, Violin, and Piano Bohuslav Martinu Allegro poco moderato (1890-1959) Adagio Allegretto Moderato (poco Allegro) ~- Sonata a tre (1982) KarelHusa Con intensita (b. 1921) Con sensitivita Con velocita The reverberative acoustics of Duncan Recital Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are prohibited. BIOGRAPHIES LEONE BUYSE is Professor of Flute and Chamber Music at the Shepherd School ofMusic. In 199 3 she relinquished her principal posi tions with the Boston Symphony Orchestra to pursue a more active teach ~ · ing and solo career after twenty-two years as an orchestral musician. Previously assistant principal flutist of the San Francisco Symphony and ~_..; solo piccoloist of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, Ms. Buyse has I appeared as soloist with those orchestras, as well as with l'Orchestre .. de la Suisse Romande, the Boston Symphony and Boston Pops, the Utah Symphony, and the New Hampshire Music Festival, of which she was I ., ' principal flutist for ten years. -

2019 Performance Competitions Program Booklet

WASHINGTON STATE MUSIC TEACHERS ASSOCIATION AFFILIATED WITH MUSIC TEACHERS NATIONAL ASSOCIATION 2019 Performance Competitions Program Booklet Junior Piano | String Senior Piano | Piano Duet | String | Woodwind Young Artist Piano | String | Woodwind | Brass Whitworth University Spokane, Washington November 9-10, 2019 2019 WASHINGTON STATE PERFORMANCE COMPETITIONS MTNA Junior Piano Competition 3 Kawai America is the sponsor of the national awards MTNA Junior String Competition 7 Yamaha Corporation of America, Orchestral Strings Division, is the sponsor of the national awards MTNA Senior Piano Competition 10 Yamaha Corporation of America, Piano Division, is the sponsor of the national awards MTNA Senior Piano Duet Competition 15 Weekley & Arganbright is the sponsor of the national awards MTNA Senior String Competition 17 MTNA Foundation Fund is the sponsor of the national awards MTNA Senior Woodwind Competition 20 MTNA Foundation Fund is the sponsor of the national awards MTNA Young Artist Piano Competition 23 Steinway & Sons is the sponsor of the national awards MTNA Young Artist String Competition 26 MTNA Foundation Fund is the sponsor of the national awards MTNA Young Artist Woodwind Competition 28 MTNA Foundation Fund is the sponsor of the national awards MTNA Young Artist Brass Competition 31 MTNA Foundation Fund is the sponsor of the national awards Washington State MTNA Past Competition Winners 33 Junior Performance 33 Senior Performance 34 Young Artist Performance 35 Composition 36 WSMTA Scholarship Fund 37 Washington State MTNA Performance Competition Committee Junior Competitions Coordinator Karen Scholten Senior Competitions Coordinator Mary Kaye Owen, NCTM Young Artist Competitions Coordinator Laura Curtis Competitions Chair Colleen Hunter, NCTM WSMTA President Karen Hollenback, NCTM WSMTA President-elect Kathy Mortensen Program Booklet Samantha Yeung Thank you to our Piano Division Judges Dr. -

Commemorative Concert the Suntory Music Award

Commemorative Concert of the Suntory Music Award Suntory Foundation for Arts ●Abbreviations picc Piccolo p-p Prepared piano S Soprano fl Flute org Organ Ms Mezzo-soprano A-fl Alto flute cemb Cembalo, Harpsichord A Alto fl.trv Flauto traverso, Baroque flute cimb Cimbalom T Tenor ob Oboe cel Celesta Br Baritone obd’a Oboe d’amore harm Harmonium Bs Bass e.hrn English horn, cor anglais ond.m Ondes Martenot b-sop Boy soprano cl Clarinet acc Accordion F-chor Female chorus B-cl Bass Clarinet E-k Electric Keyboard M-chor Male chorus fg Bassoon, Fagot synth Synthesizer Mix-chor Mixed chorus c.fg Contrabassoon, Contrafagot electro Electro acoustic music C-chor Children chorus rec Recorder mar Marimba n Narrator hrn Horn xylo Xylophone vo Vocal or Voice tp Trumpet vib Vibraphone cond Conductor tb Trombone h-b Handbell orch Orchestra sax Saxophone timp Timpani brass Brass ensemble euph Euphonium perc Percussion wind Wind ensemble tub Tuba hichi Hichiriki b. … Baroque … vn Violin ryu Ryuteki Elec… Electric… va Viola shaku Shakuhachi str. … String … vc Violoncello shino Shinobue ch. … Chamber… cb Contrabass shami Shamisen, Sangen ch-orch Chamber Orchestra viol Violone 17-gen Jushichi-gen-so …ens … Ensemble g Guitar 20-gen Niju-gen-so …tri … Trio hp Harp 25-gen Nijugo-gen-so …qu … Quartet banj Banjo …qt … Quintet mand Mandolin …ins … Instruments p Piano J-ins Japanese instruments ● Titles in italics : Works commissioned by the Suntory Foudation for Arts Commemorative Concert of the Suntory Music Award Awardees and concert details, commissioned works 1974 In Celebration of the 5thAnniversary of Torii Music Award Ⅰ Organ Committee of International Christian University 6 Aug. -

Everything Essential

Everythi ng Essen tial HOW A SMALL CONSERVATORY BECAME AN INCUBATOR FOR GREAT AMERICAN QUARTET PLAYERS BY MATTHEW BARKER 10 OVer tONeS Fall 2014 “There’s something about the quartet form. albert einstein once Felix Galimir “had the best said, ‘everything should be as simple as possible, but not simpler.’ that’s the essence of the string quartet,” says arnold Steinhardt, longtime first violinist of the Guarneri Quartet. ears I’ve been around and “It has everything that is essential for great music.” the best way to get students From Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert through the romantics, the Second Viennese School, Debussy, ravel, Bartók, the avant-garde, and up to the present, the leading so immersed in the act of composers of each generation reserved their most intimate expression and genius for that basic ensemble of two violins, a viola, and a cello. music making,” says Steven Over the past century america’s great music schools have placed an increasing emphasis tenenbom. “He was old on the highly specialized and rigorous discipline of quartet playing. among them, Curtis holds a special place despite its small size. In the last several decades alone, among the world and new world.” majority of important touring quartets in america at least one chair—and in some cases four—has been filled by a Curtis-trained musician. (Mr. Steinhardt, also a longtime member of the Curtis faculty, is one.) looking back, the current golden age of string quartets can be traced to a mission statement issued almost 90 years ago by early Curtis director Josef Hofmann: “to hand down through contemporary masters the great traditions of the past; to teach students to build on this heritage for the future.” Mary louise Curtis Bok created a haven for both teachers and students to immerse themselves in music at the highest levels without financial burden. -

Emerson String Quartet Calidore String Quartet

Emerson String Quartet and Calidore String Quartet Emerson String Quartet Eugene Drucker / Violin Philip Setzer / Violin Lawrence Dutton / Viola Paul Watkins / Cello Calidore String Quartet Jeffrey Myers / Violin Ryan Meehan / Violin Jeremy Berry / Viola Estelle Choi / Cello Thursday Evening, October 5, 2017 at 7:30 Rackham Auditorium Ann Arbor Ninth Performance of the 139th Annual Season 55th Annual Chamber Arts Series PROGRAM Richard Strauss Capriccio, Op. 85 (excerpt) String Sextet Calidore String Quartet, Mr. Dutton, Mr. Watkins Anton Bruckner String Quintet in F Major, WAB 112 (excerpt) Adagio Emerson String Quartet, Mr. Berry Dmitri Shostakovich Two Pieces for String Octet, Op. 11 Prelude: Adagio Scherzo: Allegro molto Calidore String Quartet, Emerson String Quartet Intermission Felix Mendelssohn Octet in E-flat Major, Op. 20 Allegro moderato con fuoco Andante This evening’s performance is made possible by endowed support from the Ilene H. Forsyth Chamber Scherzo: Allegro leggierissimo Arts Endowment Fund, which supports an annual UMS Chamber Arts performance in perpetuity. Presto Media partnership is provided by WGTE 91.3 FM and WRCJ 90.9 FM. The Emerson String Quartet appears by arrangement with IMG Artists. Emerson String Quartet, Calidore String Quartet The Calidore String Quartet appears by arrangement with Opus 3 Artists. In consideration of the artists and the audience, please refrain from the use of electronic devices during the performance. The photography, sound recording, or videotaping of this performance is prohibited. 3 CAPRICCIO, OP. 85 (EXCERPT) (1941–42) hands of Strauss’s official librettist, music of that period. At the same Joseph Gregor, however, the opera time, Strauss remained faithful to his Richard Strauss did not progress to the composer’s own post-Romantic idiom, which no Born June 11, 1864 in Munich, Germany satisfaction and was temporarily one handled more beautifully or more Died September 8, 1949 in Garmisch-Partenkirchen set aside in favor of other projects. -

Classical Series 1 2019/2020

classical series 2019/2020 season 1 classical series 2019/2020 Meet us at de Doelen! Bang in the middle of Rotterdam’s vibrant city centre and at a stone’s throw from the magnificent Central Station, you find concert hall de Doelen. A perfect architectural example of the Dutch post-war reconstruction era, as well as a veritable people’s palace, featuring international programming and festivals. Built in the sixties, its spacious state- of-the-art auditoria and foyers continue to make it look and feel like a timelessly modern and dynamic location indeed. De Doelen is home to the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, with the very young and talented conductor Lahav Shani at its helm. But that is not all! With over 600 concerts held annually, our programming is delightfully varied, ranging from true crowd-pullers to concerts catering to connoisseurs, and from children’s concerts to performances of world music, jazz and hip-hop. What’s more, de Doelen is the beating heart of renowned cultural festivals such as the IFFR, Poetry International, Rotterdam Unlimited, HipHopHouse’s Make A Scene and RPhO’s Gergiev Festival. Check this brochure for this season’s programme. You will hopefully be as thrilled as we are with what’s on offer. Meet us at de Doelen and enjoy! Janneke Staarink, director & de Doelen team Janneke Staarink © Sanne Donders classical series 3 contents classical series 2019/2020 season preface 3 Pierre-Laurent Aimard © Marco Borggreve Grupo Ruta de la Esclavitud © Claire Xavier classical series 6 - 29 suggestions per subject 30 chronological overview 32 piano great baroque ordering information 36 From classics to cross-overs: the versatility of the This series features great themes and signature baroque floor plans 38 piano takes centre stage. -

Kronos Quartet

K RONOS QUARTET SUNRISE o f the PLANETARY DREAM COLLECTOR Music o f TERRY RILEY TERRY RILEY (b. 1935) KRONOS QUARTET David Harrington, VIOLIN 1. Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector 12:31 John Sherba, VIOLIN Hank Dutt, VIOLA 2. One Earth, One People, One Love 9:00 CELLO (1–2) from Sun Rings Sunny Yang, Joan Jeanrenaud, CELLO (3–4, 6–16) 3. Cry of a Lady 5:09 with Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares Jennifer Culp, CELLO (5) Dora Hristova, conductor 4. G Song 9:39 5. Lacrymosa – Remembering Kevin 8:28 Cadenza on the Night Plain 6. Introduction 2:19 7. Cadenza: Violin I 2:34 8. Where Was Wisdom When We Went West? 3:05 9. Cadenza: Viola 2:24 10. March of the Old Timers Reefer Division 2:19 11. Cadenza: Violin II 2:02 12. Tuning to Rolling Thunder 4:53 13. The Night Cry of Black Buffalo Woman 2:53 1 4. Cadenza: Cello 1:08 15. Gathering of the Spiral Clan 5:24 16. Captain Jack Has the Last Word 1:42 from left: Joan Jeanrenaud, John Sherba, Terry Riley, Hank Dutt, and David Harrington (1983, photo by James M. Brown) Sunrise of the Planetary possibilities of life. It helped the Dream Collector (1980) imagination open up to the possibilities It had been raining steadily that day surrounding us, to new possibilities in 1980 when the Kronos Quartet drove up curiosity he stopped by to hear the quartet Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector for interpretation.” —John Sherba to the Sierra Foothills to receive Sunrise practice. -

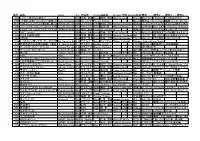

番号 曲名 Name インデックス 作曲者 Composer 編曲者 Arranger作詞

番号 曲名 Name インデックス作曲者 Composer編曲者 Arranger作詞 Words出版社 備考 備考2 備考3 備考4 595 1 2 3 ~恋がはじまる~ 123Koigahajimaru水野 良樹 Yoshiki鄕間 幹男 Mizuno Mikio Gouma ウィンズスコアWSJ-13-020「カルピスウォーター」CMソングいきものがかり 1030 17世紀の古いハンガリー舞曲(クラリネット4重奏)Early Hungarian 17thDances フェレンク・ファルカシュcentury from EarlytheFerenc 17th Hungarian century Farkas Dances from the Musica 取次店:HalBudapest/ミュージカ・ブダペスト Leonard/ハル・レナード編成:E♭Cl./B♭Cl.×2/B.Cl HL50510565 1181 24のプレリュードより第4番、第17番24Preludes Op.28-4,1724Preludesフレデリック・フランソワ・ショパン Op.28-4,17Frédéric福田 洋介 François YousukeChopin Fukuda 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2019年2月スコアは4番と17番分けてあります 840 スリー・ラテン・ダンス(サックス4重奏)3 Latin Dances 3 Latinパトリック・ヒケティック Dances Patric 尾形Hiketick 誠 Makoto Ogata ブレーンECW-0010Sax SATB1.Charanga di Xiomara Reyes 2.Merengue Sempre di Aychem sunal 3.Dansa Lationo di Maria del Real 997 3☆3ダンス ソロトライアングルと吹奏楽のための 3☆3Dance福島 弘和 Hirokazu Fukushima 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2017年6月号サンサンダンス(日本語) スリースリーダンス(英語) トレトレダンス(イタリア語) トゥワトゥワダンス(フランス語) 973 360°(miwa) 360domiwa、NAOKI-Tmiwa、NAOKI-T西條 太貴 Taiki Saijyo ウィンズスコアWSJ-15-012劇場版アニメ「映画ドラえもん のび太の宇宙英雄記(スペースヒーローズ)」主題歌 856 365日の紙飛行機 365NichinoKamihikouki角野 寿和 / 青葉 紘季Toshikazu本澤なおゆき Kadono / HirokiNaoyuki Honzawa Aoba M8 QH1557 歌:AKB48 NHK連続テレビ小説『あさが来た』主題歌 685 3月9日 3Gatu9ka藤巻 亮太 Ryouta原田 大雪 Fujimaki Hiroyuki Harada ウィンズスコアWSL-07-0052005年秋に放送されたフジテレビ系ドラマ「1リットルの涙」の挿入歌レミオロメン歌 1164 6つのカノン風ソナタ オーボエ2重奏Six Canonic Sonatas6 Canonicゲオルク・フィリップ・テレマン SonatasGeorg ウィリアム・シュミットPhilipp TELEMANNWilliam Schmidt Western International Music 470 吹奏楽のための第2組曲 1楽章 行進曲Ⅰ.March from Ⅰ.March2nd Suiteグスタフ・ホルスト infrom F for 2ndGustav Military Suite Holst -

Schumann Quartett

Candlelight Concert Society Presents SCHUMANN QUARTETT ERIK SCHUMANN, violin KEN SCHUMANN, violin LIISA RANDALU, viola MARK SCHUMANN, cello Saturday, February 22, 2020, 7:30 pm Smith Theatre–Horowitz Visual & Performing Arts Center Howard Community College This performance is sponsored by Rosalie Lijinsky Chadwick in memory of William Lijinsky WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) Quartet in D major, K. 499, “Hoffmeister” Allegretto Menuetto: Allegretto Adagio Allegro DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975) Quartet no. 9 in E-flat Major, op. 117 Moderato con moto Adagio Allegretto Adagio Allegro Intermission BEDŘICH SMETANA (1824–1884) Quartet no. 1 in E minor, “From my Life” Allegro vivo appassionato Allegro moderato alla Polka Largo sostenuto Vivace Discography: BERLIN CLASSICS Management: ARTS MANAGEMENT GROUP, INC., https://www.artsmg.com/ deepening plot. Some of Mozart’s densest coun- Program Notes terpoint appears in the Menuetto, which is at the same time intense and elegant. Following traditional Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) minuet and trio form, the robust initial repeated sec- QUARTET IN D MAJOR, K. 499, “HOFFMEISTER” tions give over to a trio, which in this case introduces a tentative element. The trio ends one beat too The publisher and skilled am- early, as if the composer were tripping over him- ateur violinist Franz Anton self in his eagerness to get back to the confidence Hoffmeister (1754-1812) of the minuet. A slow movement, marked Adagio, was a friend, colleague, and brings repose in the form of a homophonic texture, benefactor of Mozart. In but there is a hint of melancholy in the chromatic 1785, Hoffmeister agreed ornamentation and chord progressions. -

An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru

Flute Repertoire from Japan: An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru Hayashi, and Akira Tamba D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Daniel Ryan Gallagher, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Caroline Hartig Professor Karen Pierson 1 Copyrighted by Daniel Ryan Gallagher 2019 2 Abstract Despite the significant number of compositions by influential Japanese composers, Japanese flute repertoire remains largely unknown outside of Japan. Apart from standard unaccompanied works by Tōru Takemitsu and Kazuo Fukushima, other Japanese flute compositions have yet to establish a permanent place in the standard flute repertoire. The purpose of this document is to broaden awareness of Japanese flute compositions through the discussion, analysis, and evaluation of substantial flute sonatas by three important Japanese composers: Ikuma Dan (1924-2001), Hikaru Hayashi (1931- 2012), and Akira Tamba (b. 1932). A brief history of traditional Japanese flute music, a summary of Western influences in Japan’s musical development, and an overview of major Japanese flute compositions are included to provide historical and musical context for the composers and works in this document. Discussions on each composer’s background, flute works, and compositional style inform the following flute sonata analyses, which reveal the unique musical language and characteristics that qualify each work for inclusion in the standard flute repertoire. These analyses intend to increase awareness and performance of other Japanese flute compositions specifically and lesser- known repertoire generally.