An Overview of Media Interventions in Tobacco Control: Strategies and Themes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brands MSA Manufacturers Dateadded 1839 Blue 100'S Box

Brands MSA Manufacturers DateAdded 1839 Blue 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Blue King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Blue 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Blue King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Green 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Menthol Green King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Non Filter King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Red 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Red King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 16oz Blue Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 16oz Full Flavor Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 16oz Menthol Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 6 oz Full Flavor Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 6oz Blue Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 RYO 6oz Menthol Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Silver 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1839 Silver King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Blue 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Blue King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Menthol Green 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Menthol Green King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Menthol Silver 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Non Filter King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Red 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Red King Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 1st Class Silver 100's Box Premier Manufacturing 7/1/2021 24/7 Gold 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Gold King Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Menthol 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Menthol Gold 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Menthol King Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Red 100's Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Red King Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 24/7 Silver Xcaliber International 7/1/2021 Amsterdam Shag 35g Pouch or 150g Tin Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S 7/1/2021 Bali Shag RYO gold or navy pouch or canister Top Tobacco L.P. -

Heated Cigarettes: How States Can Avoid Getting Burned

HEATED CIGARETTES: HOW STATES CAN AVOID GETTING BURNED 8/30/18 1 HEATED CIGARETTES HOW STATES CAN AVOID GETTING BURNED 8/30/18 2 THE PUBLIC HEALTH LAW CENTER 8/30/18 3 8/30/18 4 LEGAL TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE Legal Research Policy Development, Implementation, Defense Publications Trainings Direct Representation Lobby 8/30/18 5 HEATED CIGARETTES HOW STATES CAN AVOID GETTING BURNED • Presenters: – Kristy Marynak, MPP, Public Health Analyst, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – Hudson Kingston, JD, LLM, Staff Attorney, Tobacco Control Legal Consortium at the Public Health Law Center 8/30/18 6 HEATED CIGARETTES HOW STATES CAN AVOID GETTING BURNED • Heated cigarettes on the global market • Distinguishing features 1. Heating at a temperature lower than conventional cigarettes that produce an inhalable aerosol • Heated Cigarettes: 450-700° F (generally) • Conventional cigarettes: 1250 – 1300 °F, • (max: 1500 °F) 2. Processed, commercial tobacco leaf is the nicotine source, flavor source, or both 8/30/18 7 HEATED CIGARETTES HOW STATES CAN AVOID GETTING BURNED Federal Regulation • Pre-Market Review • Modified Risk Tobacco Product Application • Vapeleaf 8/30/18 8 Heated Tobacco Products: Considerations for Public Health Policy and Practice KRISTY MARYNAK, MPP LEAD PUBLIC HEALTH ANALYST CDC OFFICE ON SMOKING AND HEALTH TOBACCO CONTROL LEGAL CONSORTIUM WEBINAR AUGUST 2018 8/30/18 9 What’s the public health importance of this topic? The landscape of tobacco products is continually changing By being proactive and anticipating new products, we can -

Pyramid Cigarettes

** Pyramid Cigarettes ** Pyramid Red Box 10 Carton Pyramid Blue Box 10 Carton Pyramid Menthol Gold Box 10 Carton Pyramid Menthol Silver Box 10 Carton Pyramid Orange Box 10 Carton Pyramid Red Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Blue Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Menthol Gold Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Menthol Silver Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Orange Box 100 10 Carton Pyramid Non Filter Box 10 Carton ** E Cigarettes ** Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol Gold 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol High 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol Platinum 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol Sterling 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Menthol Zero 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Gold 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette High 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Sterling 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Platinum 24 Box Logic Disposable E Cigarette Zero 24 Box ** Premium Cigars ** Acid Krush Classic Blue 5-10pk Tin Acid Krush Classic Mad Morado 5-10pk Tin Acid Krush Classic Gold 5-10pk Tin Acid Krush Classic Red 5-10pk Tin Acid Kuba Kuba 24 Box Acid Blondie 40 Box Acid C-Note 20 Box Acid Kuba Maduro 24 Box Acid 1400cc 18 Box Acid Blondie Belicoso 24 Box Acid Kuba Deluxe 10 Box Acid Cold Infusion 24 Box Ambrosia Clove Tiki 10 Box Acid Larry 10-3pk Pack Acid Deep Dish 24 Box Acid Wafe 28 Box Acid Atom Maduro 24 Box Acid Nasty 24 Box Acid Roam 10 Box Antano Dark Corojo Azarosa 20 Box Antano Dark Corojo El Martillo 20 Box Antano Dark Corojo Pesadilla 20 Box Antano Dark Corojo Poderoso 20 Box Natural Dirt 24 Box Acid Liquid 24 Box Acid Blondie -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

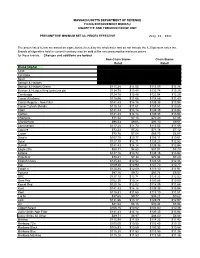

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

Associations Between Black and Mild Cigar Pack Size and Demographics and Tobacco Use Behaviors Among US Adults

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Associations between Black and Mild Cigar Pack Size and Demographics and Tobacco Use Behaviors among US Adults Ollie Ganz 1,* , Jessica L. King 2 , Daniel P. Giovenco 3, Mary Hrywna 1, Andrew A. Strasser 4 and Cristine D. Delnevo 1 1 Rutgers Center for Tobacco Studies, Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA; [email protected] (M.H.); [email protected] (C.D.D.) 2 Department of Health & Kinesiology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, New York, NY 110032, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +848-932-1851 Abstract: Pack size is an important pricing strategy for the tobacco industry, but there is limited data on how users differ based on preferred pack size for cigar products. Using data from Wave 4 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study, this study identified differences in adult cigar user characteristics based on pack size purchasing behavior among users of a top cigar brand, Black and Mild. Weighted chi-square tests were used to examine the associations between Black and Mild pack size and sociodemographic, cigar and other substance use characteristics. Overall, our study found that users of Black and Mild cigars differ by demographic, cigar and other Citation: Ganz, O.; King, J.L.; tobacco use characteristics based on preferred pack size, with smaller packs appealing to younger, Giovenco, D.P.; Hrywna, M.; Strasser, A.A.; Delnevo, C.D. -

Vintage Cigarette Ad Exhibit Focuses on Industry Manipulation He Kindly Looking Doctor in 1920 to 1954

& ■ A monthly section on physical and mental well-being. April 11, 2007 SECTION 2 A LSO INSIDE C ALENDAR 30 |C LASSIFIEDS 39 Era of by D Sue Dremann Photo by Marjan Sadoughi Dr. Robert Jackler poses in front of a display of ads featuring doctors purportedly promoting cigarettes. Vintage cigarette ad exhibit focuses on industry manipulation he kindly looking doctor in 1920 to 1954. and political winds of the times. a white lab coat holds up The exhibit sheds light on The golden age of cigarette ads Ta package of Lucky Strike tobacco company tactics by show- ended in 1954, when the Federal cigarettes, gazing at them fondly. ing how orchestrated campaigns Trade Commission clamped “20,679 Physicians say ‘Luck- have worked over time. The down on tobacco companies ies are less irritating.’ Your Jacklers and Robert Proctor, a making health claims. Throat Protection against irri- Stanford professor of history and Tobacco was a known cause of tation, against cough,” the col- science, are writing a book featur- oral cancer as early as the 18th orful ad proclaims. ing many of the vintage ads. century, but the link to lung Dr. Robert Jackler, professor The exhibition has poignancy cancer wasn’t accepted until the and chair of otolaryngology at for Dr. Jackler, whose mother, early 1940s and ‘50s, Dr. Jack- Stanford, was struck by the ad’s a long-term smoker, was diag- ler said. When physician Isaac audacious misuse of the physi- nosed with lung cancer shortly Adler made the connection in cian’s iconic image of authority. -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 4/29/10

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 4/29/10 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

A Companion to Andrei Platonov's the Foundation

A Companion to Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit Studies in Russian and Slavic Literatures, Cultures and History Series Editor: Lazar Fleishman A Companion to Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit Thomas Seifrid University of Southern California Boston 2009 Copyright © 2009 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-934843-57-4 Book design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2009 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com iv Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE Platonov’s Life . 1 CHAPTER TWO Intellectual Influences on Platonov . 33 CHAPTER THREE The Literary Context of The Foundation Pit . 59 CHAPTER FOUR The Political Context of The Foundation Pit . 81 CHAPTER FIVE The Foundation Pit Itself . -

Page 1 of 15

Updated September14, 2021– 9:00 p.m. Date of Next Known Updates/Changes: *Please print this page for your own records* If there are any questions regarding pricing of brands or brands not listed, contact Heather Lynch at (317) 691-4826 or [email protected]. EMAIL is preferred. For a list of licensed wholesalers to purchase cigarettes and other tobacco products from - click here. For information on which brands can be legally sold in Indiana and those that are, or are about to be delisted - click here. *** PLEASE sign up for GovDelivery with your EMAIL and subscribe to “Tobacco Industry” (as well as any other topic you are interested in) Future lists will be pushed to you every time it is updated. *** https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/INATC/subscriber/new RECENTLY Changed / Updated: 09/14/2021- Changes to LD Club and Tobaccoville 09/07/2021- Update to some ITG list prices and buydowns; Correction to Pall Mall buydown 09/02/2021- Change to Nasco SF pricing 08/30/2021- Changes to all Marlboro and some RJ pricing 08/18/2021- Change to Marlboro Temp. Buydown pricing 08/17/2021- PM List Price Increase and Temp buydown on all Marlboro 01/26/2021- PLEASE SUBSCRIBE TO GOVDELIVERY EMAIL LIST TO RECEIVE UPDATED PRICING SHEET 6/26/2020- ***RETAILER UNDER 21 TOBACCO***(EFF. JULY 1) (on last page after delisting) Minimum Minimum Date of Wholesale Wholesale Cigarette Retail Retail Brand List Manufacturer Website Price NOT Price Brand Price Per Price Per Update Delivered Delivered Carton Pack Premier Mfg. / U.S. 1839 Flare-Cured Tobacco 7/15/2021 $42.76 $4.28 $44.00 $44.21 Growers Premier Mfg. -

Newsletter 09/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 09/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 332 - August 2013 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 09/13 (Nr. 332) August 2013 editorial Neues Video auf unserem Youtube-Kanal! http://www.youtube.com/user/laserhotline WOCHENENDKRIEGER DIE FILMMUSIK Wir haben Uwe Schenk, den Komponisten der Musik zu dem Film „Wochenendkrieger“, in seinem Studio besucht. Anhand von Beispielen demonstriert er seine Arbeitsweise und erzählt über den sinfonischen Score zu Andreas Geigers Dokumentarfilm. Viel Spaß bei Anschauen wünscht Ihr LASER HOTLINE Team! LASER HOTLINE Seite 2 Newsletter 09/13 (Nr. 332) August 2013 Batfleck and Wonder-Where-She-Is-Woman Vereinzelte Sonnenstrahlen scheinen durch die Wol- Joker gecastet wurde. Dass er sich in Batman verlie- kendecke durch und kitzeln mir das Gesicht. Schlaf- ben würde, wurde gehöhnt, und dass er die Persön- trunken greife ich nach meinem iPhone, reibe mir die lichkeit und schauspielerischen Fähigkeiten eines Augen und rufe mein Twitter auf. Das Internet ist in Blattes Salat habe. Und nun ist Ledgers Joker eine Rage, nur ein Thema beherrscht meine Timeline: Ben Legende und wird verehrt. Nicht nur, weil es seine Affleck ist offiziell der neue Batman! Missmut, Auf- letzte Performance war und er alles dafür gegeben ruhr, Revolution! Alle sind sich einig, dass Affleck der hat. Ben Affleck ist heutzutage ein weit besserer totale Fehlgriff für den Dunklen Ritter ist. Ich lege das Schauspieler als er es zu Zeiten von Jack Ryan und iPhone beiseite und stöhne. -

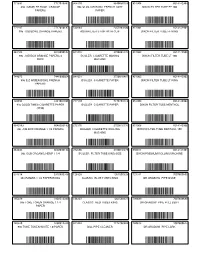

Visual Foxpro

771891 7717010891 864110 8640080110 851904 8514142904 49¢ GAMBLER BOWL ORANGE 99¢-$1.49 JOB BOWL FRENCH LGHT DIXON FILTER TUBE FF 100 PAPERS PAPER 9` S 9K 771187 7717010187 540164 2355869100 851901 8514142901 99¢ JOB BOWL ORANGE PAPERS AQUAFILTER STRIP WITH CLIP DIXON FILTER TUBE FF KING [ 9I 9 864103 8640090103 041015 2720001575 851905 8514142905 99¢ JOB BOX ORANGE PAPERS 4 BUGLER CIGARETTE MAKING DIXON FILTER TUBE LT 100 FREE MACHINE 9n A 9U 744072 7446000054 041021 2720010487 851902 8514142902 99¢ E-Z WIDER BOWL FRENCH BUGLER CIGARETTE PAPER DIXON FILTER TUBE LT KING PAPERS z U 9 123896 1231901896 717110 7173798110 851903 8514142903 99¢ GOOD TIMES-CIGARETTE PAPER BUGLER CIGARETTE PAPER DIXON FILTER TUBE MENTHOL (2F99) 99 9W 9A 8640183 8640000183 272176 2720010176 851906 8514142906 99¢ JOB BOX ORANGE 1 1/4 PAPERS BUGLER CIGARETTE ROLLING DIXON FILTER TUBE MENTHOL 100 MACHINE * 9_ 864043 8640090124 272405 2720010479 685011 8514147401 99¢ OCB ORGANIC HEMP 1 1/4 BUGLER FILTER TUBE KING SIZE DIXON PREMIUM ROLLING MACHINE 9 9` 531318 5310900318 126328 1261500328 721331 7007600605 99¢ RAMZIS 1 1/4 PAPER BOWL CLASSIC BLUE TUBES KING DR GRABOW PIPE DUKE 9 9 185320 1850512320 126327 1261500327 700680 7007600680 99¢ TOKE TOKEN ORANGE 1 1/4 CLASSIC RED TUBES KING DR GRABOW PIPE FULL BENT PAPER i D 185330 1850512330 041048 7173700802 700613 7007600613 99¢ TOKE TOKEN WHITE 1.0 PAPER DILL PIPE CLEANER DR GRABOW PIPE LARK r 700612 7007600612 771077 7717026077 771086 7717026086 DR GRABOW PIPE OMEGA GAMBLER TUBE CUT TUBE 100 GOLD GAMBLER CIGARETTE