A New Alvarezsaurian Theropod from the Upper Jurassic Shishugou

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dashanpu Dinosaur Fauna of Zigong Sichuan Short Report V - Labyrinthodont Amphibia

The Dashanpu Dinosaur Fauna of Zigong Sichuan Short Report V - Labyrinthodont Amphibia Zhiming Dong (Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology, Paleoanthropology, Academia Sinica) Vertebrata PalAsiatica Volume XXIII, No. 4 October, 1985 pp. 301-305 Translated by Will Downs Department of Geology Bilby Research Center Northern Arizona University December, 1990 Abstract A brief discussion is presented on the morphological characteristics and phylogenetic position of Sinobrachyops placenticephalus (gen. et sp. nov.). The specimen is derived from the well-known Middle Jurassic Dashanpu dinosaur quarries of Zigong County, Sichaun Province. Sinobrachyops is the youngest geological occurrence of a labyrinthodont amphibian known to date. Its discovery extends the upper geochronological limit for the Labyrinthodontia into the Middle Jurassic. Introduction The first fossils collected from Dashanpu, Zigong, in 1979, were a pair of rhachitomous vertebrae. This discovery created a sense of perplexity among the workers, for the morphology of these pleurocentra and intercentra suggested an assignment to the Labyrinthodontia. This group of amphibians, however, was traditionally believed to have become extinct in the Late Triassic, a traditional concept that must be abandoned if scientific investigation is to be advanced and left unfettered. In 1983 the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology, Paleoanthropology Academia Sinica launched a paleontological expedition in the Shishugou Formation (Middle-Late Jurassic) from the Kelameili region, northeast Jungar Basin, Xinjiang Autonomous Region, where several rhachitomous vertebrae were discovered. Later, a fragmentary skull of a labyrinthodont amphibian was collected, confirming that this group extended into the Middle Jurassic. The discovery from the Shishugou Formation convinced the workers that the rhachitomous vertebrae at Dashanpu belonged to the Labyrinthodontia. -

First Turtle Remains from the Middle-Late Jurassic Yanliao Biota, NE China

Vol.7, No.1 pages 1-11 Science Technology and Engineering Journal (STEJ) Research Article First Turtle Remains from the Middle-Late Jurassic Yanliao Biota, NE China Lu Li1,2,3, Jialiang Zhang4, Xiaolin Wang1,2,3, Yuan Wang1,2,3 and Haiyan Tong1,5* 1 Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China 2 CAS Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Beijing 100044, China 3 College of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of China Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China 4 State Key Laboratory of Biogeology and Environmental Geology, China University of Geosciences, Beijing 100083, China 5 Palaeontological Research and Education Centre, Mahasarakham University, Kantarawichai, Maha Sarakham 44150, Thailand * Corresponding author: [email protected] (Received: 14th August 2020, Revised: 11th January 2021, Accepted: 9th March 2021) Abstract - The Middle-Late Jurassic Yanliao Biota, preceding the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota in NE China has yielded a rich collection of plant, invertebrate and vertebrate fossils. But contrary to the Jehol Biota which is rich in freshwater vertebrates, in the Yanliao Biota the aquatic reptiles are absent, and turtles have not been reported so far. In this paper, we report on the first turtle remains from the Yanliao Biota. The material consists of a partial skeleton from the Upper Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation of Bawanggou site (Qinglong, Hebei Province, China). Characterized by a broad skull with a pair of sulci carotici and a remnant of an interpterygoid vacuity, a well-developed anterior lobe of the plastron with mesiolaterally elongated epiplastra and a relatively large oval entoplastron; it is assigned to Annemys sp. -

Final Summary Report of the Research Project (ERB, 624732)

Final Summary Report of the Research Project (ERB, 624732): Introduction: Birds represent one of the most remarkable radiations in the history of life. The origin of flight and the diversification of birds have become classic ‘textbook’ examples for discussions about evolutionary models, biomechanics, the history of life, and phylogenetics. Much attention has focused on the discovery and description of new fossils, both derived theropods and basal birds: in particular, sediments of the Jehol Group in Liaoning and other provinces in China have doubled the number of Mesozoic bird taxa and have considerably expanded our knowledge of derived theropod dinosaurs. All this wealth of fossil data and new phylogenetic studies have established the relationships of basal bird groups, as well as their phylogenetic nesting among theropod dinosaurs, with dromaeosaurid and troodontid theropods as their closest sister groups. The mode and tempo of avian evolution have received much attention in recent years, thanks to the assembly of more complete datasets, the ongoing flow of new specimens and taxa, and the development of new techniques of macroevolutionary analysis. Recent studies revealed an avian radiation characterized by the gradual acquisition of apomorphies followed by accelerated (yet clade heterogeneous) rates of evolution. However, in the context of Coelurosauria (a diverse clade including T. rex and its kin, the ostrich-mimic ornithomimosaurs, and the sickle-clawed dromaeosaurids, among others), previous analyses have considered the skeleton as a whole, apart from studies focusing on single continuous traits. Here, I document the evolutionary dynamics of each anatomical region of the coelurosaurian skeleton. I aim at disentangling the relative role of each body part in the evolutionary dynamics of Coelurosauria. -

A New Xinjiangchelyid Turtle from the Middle Jurassic of Xinjiang, China and the Evolution of the Basipterygoid Process in Mesozoic Turtles Rabi Et Al

A new xinjiangchelyid turtle from the Middle Jurassic of Xinjiang, China and the evolution of the basipterygoid process in Mesozoic turtles Rabi et al. Rabi et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:203 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/203 Rabi et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:203 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/203 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access A new xinjiangchelyid turtle from the Middle Jurassic of Xinjiang, China and the evolution of the basipterygoid process in Mesozoic turtles Márton Rabi1,2*, Chang-Fu Zhou3, Oliver Wings4, Sun Ge3 and Walter G Joyce1,5 Abstract Background: Most turtles from the Middle and Late Jurassic of Asia are referred to the newly defined clade Xinjiangchelyidae, a group of mostly shell-based, generalized, small to mid-sized aquatic froms that are widely considered to represent the stem lineage of Cryptodira. Xinjiangchelyids provide us with great insights into the plesiomorphic anatomy of crown-cryptodires, the most diverse group of living turtles, and they are particularly relevant for understanding the origin and early divergence of the primary clades of extant turtles. Results: Exceptionally complete new xinjiangchelyid material from the ?Qigu Formation of the Turpan Basin (Xinjiang Autonomous Province, China) provides new insights into the anatomy of this group and is assigned to Xinjiangchelys wusu n. sp. A phylogenetic analysis places Xinjiangchelys wusu n. sp. in a monophyletic polytomy with other xinjiangchelyids, including Xinjiangchelys junggarensis, X. radiplicatoides, X. levensis and X. latiens. However, the analysis supports the unorthodox, though tentative placement of xinjiangchelyids and sinemydids outside of crown-group Testudines. A particularly interesting new observation is that the skull of this xinjiangchelyid retains such primitive features as a reduced interpterygoid vacuity and basipterygoid processes. -

From the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia

AMEGHINIANA (Rev. Asoc. Paleontol. Argent.) - 40 (1): 119-122. Buenos Aires, 30-03-2003 ISSN0002-7014 NOTA PALEONTOLÓGICA A new specimen of Patagonykus puertai (Theropoda: Alvarezsauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia Luis M. CHIAPPE1and Rodolfo A. CORIA2 Introduction Systematic paleontology With their short and robust forelimbs, highly ki- THEROPODA netic skulls, and a host of unique skeletal features, COELUROSAURIA alvarezsaurids are highly specialized Mesozoic ALVAREZSAURIDAEBonaparte, 1991 coelurosaurian theropods known from the Late Cretaceous of Asia, North, and South America Genus PatagonykusNovas, 1997a (Chiappe et al., 2002). Despite abundant and well- preserved material from the Gobi Desert of Patagonykussp. cf. P. puertaiNovas, 1997a Mongolia, the phylogenetic relationships of al- Figures 1 and 2 varezsaurids have remained unclear (Chiappe et Material. MCF-PVPH-102 (Museo Carmen Funes, al., 2002; Novas and Pol, 2002; Suzuki et al., 2002). Paleontología de Vertebrados; Plaza Huincul, The most basal alvarezsaurids are from South Neuquén, Argentina), an articulated phalanx 1 and 2 America and are limited to just two taxa from the (ungual) of the left manual digit I. Patagonian province of Neuquén (Argentina), Geographical provenance and geological horizon. Alvarezsaurus calvoi (Bonaparte, 1991) and Northern shore of Los Barriales lake, approximately Patagokykus puertai (Novas, 1997a), which although 80 km north Plaza Huincul. Because the specimen poorly represented are important because they was not collected by professionals, no precise strati- have been consistently interpreted as the most ple- graphic information is available; nonetheless, only siomorphic members of the group (Novas, 1996; the Late Cretaceous Neuquén Group outcrops in this Chiappe et al., 1998). area. Also, considering that the holotype specimen of Here we report on a second specimen of Patagonykus puertaiwas found in beds attributed to Patagonykus, which we assign to the species P. -

Brains and Intelligence

BRAINS AND INTELLIGENCE The EQ or Encephalization Quotient is a simple way of measuring an animal's intelligence. EQ is the ratio of the brain weight of the animal to the brain weight of a "typical" animal of the same body weight. Assuming that smarter animals have larger brains to body ratios than less intelligent ones, this helps determine the relative intelligence of extinct animals. In general, warm-blooded animals (like mammals) have a higher EQ than cold-blooded ones (like reptiles and fish). Birds and mammals have brains that are about 10 times bigger than those of bony fish, amphibians, and reptiles of the same body size. The Least Intelligent Dinosaurs: The primitive dinosaurs belonging to the group sauropodomorpha (which included Massospondylus, Riojasaurus, and others) were among the least intelligent of the dinosaurs, with an EQ of about 0.05 (Hopson, 1980). Smartest Dinosaurs: The Troodontids (like Troödon) were probably the smartest dinosaurs, followed by the dromaeosaurid dinosaurs (the "raptors," which included Dromeosaurus, Velociraptor, Deinonychus, and others) had the highest EQ among the dinosaurs, about 5.8 (Hopson, 1980). The Encephalization Quotient was developed by the psychologist Harry J. Jerison in the 1970's. J. A. Hopson (a paleontologist from the University of Chicago) did further development of the EQ concept using brain casts of many dinosaurs. Hopson found that theropods (especially Troodontids) had higher EQ's than plant-eating dinosaurs. The lowest EQ's belonged to sauropods, ankylosaurs, and stegosaurids. A SECOND BRAIN? It used to be thought that the large sauropods (like Brachiosaurus and Apatosaurus) and the ornithischian Stegosaurus had a second brain. -

New Tyrannosaur from the Mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan Clarifies Evolution of Giant Body Sizes and Advanced Senses in Tyrant Dinosaurs

Edinburgh Research Explorer New tyrannosaur from the mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan clarifies evolution of giant body sizes and advanced senses in tyrant dinosaurs Citation for published version: Brusatte, SL, Averianov, A, Sues, H, Muir, A & Butler, IB 2016, 'New tyrannosaur from the mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan clarifies evolution of giant body sizes and advanced senses in tyrant dinosaurs', Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, pp. 201600140. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1600140113 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1073/pnas.1600140113 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 Classification: Physical Sciences: Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences; Biological Sciences: Evolution New tyrannosaur from the mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan clarifies evolution of giant body sizes and advanced senses in tyrant dinosaurs Stephen L. Brusattea,1, Alexander Averianovb,c, Hans-Dieter Suesd, Amy Muir1, Ian B. Butler1 aSchool of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH9 3FE, UK bZoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. -

A New Caenagnathid Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Wangshi

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A new caenagnathid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Wangshi Group of Shandong, China, with Received: 12 October 2017 Accepted: 7 March 2018 comments on size variation among Published: xx xx xxxx oviraptorosaurs Yilun Yu1, Kebai Wang2, Shuqing Chen2, Corwin Sullivan3,4, Shuo Wang 5,6, Peiye Wang2 & Xing Xu7 The bone-beds of the Upper Cretaceous Wangshi Group in Zhucheng, Shandong, China are rich in fossil remains of the gigantic hadrosaurid Shantungosaurus. Here we report a new oviraptorosaur, Anomalipes zhaoi gen. et sp. nov., based on a recently collected specimen comprising a partial left hindlimb from the Kugou Locality in Zhucheng. This specimen’s systematic position was assessed by three numerical cladistic analyses based on recently published theropod phylogenetic datasets, with the inclusion of several new characters. Anomalipes zhaoi difers from other known caenagnathids in having a unique combination of features: femoral head anteroposteriorly narrow and with signifcant posterior orientation; accessory trochanter low and confuent with lesser trochanter; lateral ridge present on femoral lateral surface; weak fourth trochanter present; metatarsal III with triangular proximal articular surface, prominent anterior fange near proximal end, highly asymmetrical hemicondyles, and longitudinal groove on distal articular surface; and ungual of pedal digit II with lateral collateral groove deeper and more dorsally located than medial groove. The holotype of Anomalipes zhaoi is smaller than is typical for Caenagnathidae but larger than is typical for the other major oviraptorosaurian subclade, Oviraptoridae. Size comparisons among oviraptorisaurians show that the Caenagnathidae vary much more widely in size than the Oviraptoridae. Oviraptorosauria is a clade of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs characterized by a short, high skull, long neck and short tail. -

New Oviraptorid Dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Nemegt Formation of Southwestern Mongolia

Bull. Natn. Sci. Mus., Tokyo, Ser. C, 30, pp. 95–130, December 22, 2004 New Oviraptorid Dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Nemegt Formation of Southwestern Mongolia Junchang Lü1, Yukimitsu Tomida2, Yoichi Azuma3, Zhiming Dong4 and Yuong-Nam Lee5 1 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100037, China 2 National Science Museum, 3–23–1 Hyakunincho, Shinjukuku, Tokyo 169–0073, Japan 3 Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum, 51–11 Terao, Muroko, Katsuyama 911–8601, Japan 4 Institute of Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China 5 Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources, Geology & Geoinformation Division, 30 Gajeong-dong, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 305–350, South Korea Abstract Nemegtia barsboldi gen. et sp. nov. here described is a new oviraptorid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous (mid-Maastrichtian) Nemegt Formation of southwestern Mongolia. It differs from other oviraptorids in the skull having a well-developed crest, the anterior margin of which is nearly vertical, and the dorsal margin of the skull and the anterior margin of the crest form nearly 90°; the nasal process of the premaxilla being less exposed on the dorsal surface of the skull than those in other known oviraptorids; the length of the frontal being approximately one fourth that of the parietal along the midline of the skull. Phylogenetic analysis shows that Nemegtia barsboldi is more closely related to Citipati osmolskae than to any other oviraptorosaurs. Key words : Nemegt Basin, Mongolia, Nemegt Formation, Late Cretaceous, Oviraptorosauria, Nemegtia. dae, and Caudipterygidae (Barsbold, 1976; Stern- Introduction berg, 1940; Currie, 2000; Clark et al., 2001; Ji et Oviraptorosaurs are generally regarded as non- al., 1998; Zhou and Wang, 2000; Zhou et al., avian theropod dinosaurs (Osborn, 1924; Bars- 2000). -

The Nonavian Theropod Quadrate II: Systematic Usefulness, Major Trends and Cladistic and Phylogenetic Morphometrics Analyses

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272162807 The nonavian theropod quadrate II: systematic usefulness, major trends and cladistic and phylogenetic morphometrics analyses Article · January 2014 DOI: 10.7287/peerj.preprints.380v2 CITATION READS 1 90 3 authors: Christophe Hendrickx Ricardo Araujo University of the Witwatersrand Technical University of Lisbon 37 PUBLICATIONS 210 CITATIONS 89 PUBLICATIONS 324 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Octávio Mateus University NOVA of Lisbon 224 PUBLICATIONS 2,205 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Nature and Time on Earth - Project for a course and a book for virtual visits to past environments in learning programmes for university students (coordinators Edoardo Martinetto, Emanuel Tschopp, Robert A. Gastaldo) View project Ten Sleep Wyoming Jurassic dinosaurs View project All content following this page was uploaded by Octávio Mateus on 12 February 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The nonavian theropod quadrate II: systematic usefulness, major trends and cladistic and phylogenetic morphometrics analyses Christophe Hendrickx1,2 1Universidade Nova de Lisboa, CICEGe, Departamento de Ciências da Terra, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Quinta da Torre, 2829-516, Caparica, Portugal. 2 Museu da Lourinhã, 9 Rua João Luis de Moura, 2530-158, Lourinhã, Portugal. s t [email protected] n i r P e 2,3,4,5 r Ricardo Araújo P 2 Museu da Lourinhã, 9 Rua João Luis de Moura, 2530-158, Lourinhã, Portugal. 3 Huffington Department of Earth Sciences, Southern Methodist University, PO Box 750395, 75275-0395, Dallas, Texas, USA. -

Re-Evaluation of the Haarlem Archaeopteryx and the Radiation of Maniraptoran Theropod Dinosaurs Christian Foth1,3 and Oliver W

Foth and Rauhut BMC Evolutionary Biology (2017) 17:236 DOI 10.1186/s12862-017-1076-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Re-evaluation of the Haarlem Archaeopteryx and the radiation of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs Christian Foth1,3 and Oliver W. M. Rauhut2* Abstract Background: Archaeopteryx is an iconic fossil that has long been pivotal for our understanding of the origin of birds. Remains of this important taxon have only been found in the Late Jurassic lithographic limestones of Bavaria, Germany. Twelve skeletal specimens are reported so far. Archaeopteryx was long the only pre-Cretaceous paravian theropod known, but recent discoveries from the Tiaojishan Formation, China, yielded a remarkable diversity of this clade, including the possibly oldest and most basal known clade of avialan, here named Anchiornithidae. However, Archaeopteryx remains the only Jurassic paravian theropod based on diagnostic material reported outside China. Results: Re-examination of the incomplete Haarlem Archaeopteryx specimen did not find any diagnostic features of this genus. In contrast, the specimen markedly differs in proportions from other Archaeopteryx specimens and shares two distinct characters with anchiornithids. Phylogenetic analysis confirms it as the first anchiornithid recorded outside the Tiaojushan Formation of China, for which the new generic name Ostromia is proposed here. Conclusions: In combination with a biogeographic analysis of coelurosaurian theropods and palaeogeographic and stratigraphic data, our results indicate an explosive radiation of maniraptoran coelurosaurs probably in isolation in eastern Asia in the late Middle Jurassic and a rapid, at least Laurasian dispersal of the different subclades in the Late Jurassic. Small body size and, possibly, a multiple origin of flight capabilities enhanced dispersal capabilities of paravian theropods and might thus have been crucial for their evolutionary success. -

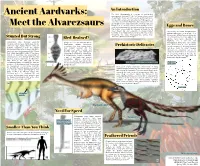

Smaller Than You Think Bird-Brained? Need for Speed

An Introduction The clade Alvarezsauria is a group of small-bodied Ancient Aardvarks: [10] maniraptoran dinosaurs. The first known alvarezsaurid, Alvarezsaurus calvoi, was discovered in partial remains in the late 20th century, and named by Jose F. Bonaparte. A. calvoi was uncovered in Argentina, but today alvarezsaurs are known to have ranged across the Americas, Asia, and Meet the Alvarezsaurs Europe.[10] It is currently estimated that members of this Eggs and Bones clade existed between the Late Jurassic and the Cretaceous. This feather covered bird-like dinosaur is known for its insect based diet and especially its unique hooked The recently discovered Bonapartenykus forelimbs. These highly derived and powerful arms evolved ultimus represents a new genus of of throughout the clade Alvarezsauridae, giving these Alvarezsaurs. A 70 million year old pocket [12] Stunted But Strong dinosaurs a predatory advantage. of fossilized bones and two eggs of this Bird-Brained? species have been discovered in Argentina. This is the first time Alvarezsaurs have strangely powerful Using a cast of a skull from the species Alvarezsaurus bones and egg remains forearms, with one large thumb claw and the Ceratonykus oculatus, researchers have been found in close proximity. other two digits highly reduced. They are reconstructed an alvarezsaurian brain. Prehistoric Delicacies Though evidence of brooding behavior radically transformed from the typical Their analysis revealed that this has been found for other theropod theropod forelimb, which is longer, with three dinosaur had acute hearing and dinosaurs, no conclusion can yet be [10] functional digits and grasping ability. Given excellent eyesight, with intelligence drawn for Alvareszsaurs as no indication their highly specialized nature, it has been comparable to living birds.