Maintaining the Balance: Whether a Collegiate Athlete’S Filing of a Federal Trademark Application Violates NCAA Bylaws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College Hoops Scoops Stony Brook, Hofstra, LIU Set to Go

Newsday.com 11/12/11 10:17 AM http://www.newsday.com/sports/college/college-hoops-scoops-1.1620561/stony-brook-hofstra-liu-set-to-go-1.3314160 College hoops scoops Stony Brook, Hofstra, LIU set to go Friday November 11, 2011 2:47 PM By Marcus Henry We’re not even technically through the first week of college basketball an already there are a couple of matchups the that should be paid attention to. Local Matchups Friday LIU at Hofstra, 7:00: After LIU’s fabulous run to the NCAA Tournament last, the Blackbirds have become one of the hottest programs in the NY Metro area. With six of its top eight players back, led by junior forward Julian Boyd the Blackbirds could he a handful for Hofstra. As for the Pride, Mo Cassara’s group could be one of the most underrated in the area. Sure, Charles Jenkins and Greg Washington are gone, but Mike Moore, David Imes, Stevie Mejia, Nathaniel Lester and Shemiye McLendon are all experienced players. It should be a good one in Hempstead. Stony Brook at Indiana, 7:00: Stony Brook and its followers have waited an entire off season for this matchup. With so much talent back and several newcomers expected to create an immediate impact, no one would be shocked to see the Seawolves win this game. Senior guard Bryan Dougher, redshirt junior forward Tommy Brenton and senior Dallis Joyner have been the key elements to Stony Brook’s rise. The Seawolves have had winning seasons two of the last three years and have finished .500 or better in the America East the last three years. -

Cleveland Cavaliers at Dallas Mavericks

Cleveland Cavaliers at Dallas Mavericks A review of FG% by distance, opponent FG% by distance, % of shots taken by distance, rebounds, assists, turnovers, points per game, steals, and blocks. Projected Starters Position Cavs Mavericks PG Kyrie Irving Yogi Ferrell SG Iman Shumpert Seth Curry SF LeBron James Wesley Mathews PF Kevin Love Harrison Barnes C Tristan Thompson Dirk Nowitzki Team Stats (Per Game) Offensive Distance Stats Distance Cavs Team Mavericks Difference Stat Cavs Mavericks Average Average Range FG% Team FG% (Advantage) Offensive Rebounds 10.2 8.2 10.1 0-3 feet 64.5% 63.1% 62.6% 1.4% (Cavs) Defensive Rebounds 34.0 29.9 33.4 3-10 feet 31.0% 43.4% 40.8% 12.4% (Mavericks) Assists 21.9 20.1 22.5 10-16 feet 42.6% 44.7% 40.7% 2.1% (Mavericks) Turnovers 13.9 12.0 14.0 16 feet - 3PT 40.8% 38.8% 39.9% 2% (Cavs) Steals 7.4 7.7 7.7 3PT 38.2% 35.6% 35.9% 2.6% (Cavs) Blocks 4.0 3.9 4.9 FG% 45.6% 43.8% 45.5% Defensive Distance Stats 3PT% 38.2% 35.6% 35.9% Distance Cavs Mavericks Average Difference Range Opponent Opponent (Advantage) Points 109.9 96.9 105.2 0-3 feet 63.2% 66.6% 62.6% 3.4% (Cavs) Possessions 99.3 93.4 98.7 3-10 feet 37.8% 41.9% 41.1% 4.1% (Cavs) 10-16 feet 41.0% 41.4% 41.0% 0.4% (Cavs) Team Stats (Per 100 Possessions) 16 feet - 3PT 40.3% 38.2% 40.1% 2.1% (Mavericks) Stat Cavs Mavericks Average 3PT 36.0% 39.5% 36.0% 3.5% (Cavs) ORTG (Points scored) 109.4 103.3 105.8 DRTG (Points allowed) 105.6 106.2 105.8 Percent of Shots Taken Distance Cavs % of Mavericks % Average Range Shots of Shots Best and Worst Ranges Compared to -

NBA Court Realty Dan Cervone (New York University), Luke Bornn (Simon Fraser University), and Kirk Goldsberry (University of Texas)

NBA Court Realty Dan Cervone (New York University), Luke Bornn (Simon Fraser University), and Kirk Goldsberry (University of Texas) The Court is a Real Estate Market Throughout a basketball possession, teams fight to control valuable court space. For example, - being near the basket or in the corner 3 areas leads to high-value shots - having the ball at the top of the arc keeps many pass options open - being open and undefended anywhere on the court eases ball movement and minimizes turnovers. Using only patterns of ball movement such as passes, we are able to infer which regions of the court teams value most, and quantify the effects of controlling such regions. This leads to new spatial characterizations of team/player strategy, and value quantifications of positioning and spacing. For instance, we can compare the value of the space the ballcarrier controls with the value of the space his teammates control to better understand how different lineups manage on- and off-ball resources. Above: Map of NBA court real estate values during 2014-15 season. Just like New York City (right), property values vary Read the full paper: dramatically by neighborhood. The hoop is the Tribeca of the NBA. 30 feet away? That's more like Astoria. The Value of a Player's Court Real Estate Investment Portfolio 3. Valuing property investments based on exchanges: When players pass the ball on offense, the team exchanges property investments. The patterns of these transactions allow us to infer the value of each player's real estate investment porfolio. For instance, in the figure on the left, if a pass between players A and B is equally likely to go A → B as B → A, we'd think A's and B's investment 1. -

Lebron's All Just Isn't Enough

Friday, June 5, 2015 MN The Plain Dealer | cleveland.com *S3 NBA FINALS Warriors 108, Cavaliers 100 (OT) Commentary LeBron’s all just isn’t enough James scores 44 points, but multiple Golden State defenders leave Cavaliers star spent GUS CHAN / THE PLAIN DEALER LeBron James looks to drive in the first quarter Thursday. James, who is playing in his sixth Finals, has an NBA-best 55 playoff games of at least 30 points, five rebounds, and five assists. Oakland, sweating out James’ miss against man can’t beat five, but James has a shot since Davidson to hear the Calif. — Andre Iguodala on the last pos- pulled this off before. James beat national media tell it scored 10 Asked if mul- session of the fourth quarter and the Detroit Piston in the 2007 con- of his 14. James scored seven of tiple rested a breathtakingly close miss on a ference finals in the pivotal double his 19. defenders were desperate corner heave after that overtime fifth game, scoring 48 The way the Warriors came the league’s by Iman Shumpert, Golden State points, including his team’s last 25 back, against a Cavaliers team way of guard- pulled away in overtime. points, 29 of its last 30 and all 18 that was at its most brainy and Bill ing players of James scored 44 points , but his in the OTs. LeBronny in the first quarter (as- Livingston his size and teammates could not make the One man supposedly can’t beat sists on seven of their 10 baskets) strength, LeB- open shots he created in the over- four, either, particularly one All- showed the truth of their pre-game ron James said, time after the 98-98 regulation tie. -

All In: Cleveland Rocks As Title Drought Ends with NBA Crown by Tom Withers, Associated Press on 06.23.16 Word Count 828

All in: Cleveland rocks as title drought ends with NBA crown By Tom Withers, Associated Press on 06.23.16 Word Count 828 Cleveland Cavaliers forward LeBron James (bottom) dunks past Golden State Warriors forward Harrison Barnes during the second half of Game 5 of basketball's NBA Finals in Oakland, California, June 13, 2016. The Cavaliers won 112-97. They went on to win the championship. Photo: John G. Mabanglo, European Pressphoto Agency via AP, Pool CLEVELAND — More tears — only this time, tears of joy. Cleveland's championship drought, crossing 52 years, generations and noted by a long list of near misses, is over at last. On Father's Day, LeBron James, the kid from nearby Akron raised by a single mother, brought the title home. As the final seconds of Cleveland's 93-89 victory at Golden State in Game 7 ticked off on the giant scoreboard inside Quicken Loans Arena, 18,000 fans, some of them strangers when Sunday night began, cried, hugged, screamed and shared a moment many of them have spent a lifetime dreaming of. They then linked arms and shouted the words to Queen's "We Are The Champions," a song that seemed reserved only for others. For the first time since 1964, when the Browns ruled the NFL, Cleveland is a title town again. With James leading the way and winning MVP honors, the Cavs became the first team in NBA Finals history to overcome a 3-1 deficit. Call it The Comeback. At 10:37 p.m., Cleveland finally exorcised decades of sports demons — the painful losses given nicknames like "The Drive" and "The Fumble" and "The Shot" — and became a title town for the first time since Dec. -

Sports Litigation Alert

Sports Litigation Alert Reprinted from Sports Litigation Alert, Volume 9, Issue 15, August 24, 2012. Copyright © 2012 Hackney Publications. Competing Before the PTO: Four Things a Professional Athlete Should Consider When Seeking a Federal Trademark Registration By Ryan S. Hilbert tion in which he can soon obtain a number trademark Today’s athletes have become increasingly proactive registrations for those words or phrases uniquely asso- and savvy about ways in which they can and should ciated with him, despite the fact that he has yet to play protect their trademarks. As an example, shortly af- an official NBA game. ter former University of North Carolina basketball With each passing year, it seems like more and star Harrison Barnes became the seventh pick in the more professional athletes are doing the same thing 2012 NBA Draft, he stated that he had already given Barnes and Davis are doing – seeking trademark tremendous thought to what his “brand” would be and protection for those words, phrases or designs with even had an artist friend design his logo. As it turns which they have become associated. Indeed, numer- out, Barnes had even gone so far as to file a trademark ous professional athletes from a variety of sports have application with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office already obtained or are seeking trademark registra- (“USPTO”) for the word mark THE BLACK FAL- tions from the USPTO, including NBA phenomenon CON – his nickname at UNC – on August 19, 2011, Jeremy Lin, (LINSANITY), former Denver Bronco months before his college career was over and almost and current New York Jet quarterback Tim Tebow a full year before he was selected to play in the NBA. -

Player Set Card # Team Print Run Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs

2013-14 Innovation Basketball Player Set Card # Team Print Run Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs 60 Atlanta Hawks 10 Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs Gold 60 Atlanta Hawks 5 DeMarre Carroll Top-Notch Autographs 88 Atlanta Hawks 325 DeMarre Carroll Top-Notch Autographs Gold 88 Atlanta Hawks 25 Dennis Schroder Main Exhibit Signatures Rookies 23 Atlanta Hawks 199 Dennis Schroder Rookie Jumbo Jerseys 25 Atlanta Hawks 199 Dennis Schroder Rookie Jumbo Jerseys Prime 25 Atlanta Hawks 25 Jeff Teague Digs and Sigs 4 Atlanta Hawks 15 Jeff Teague Digs and Sigs Prime 4 Atlanta Hawks 10 Jeff Teague Foundations Ink 56 Atlanta Hawks 10 Jeff Teague Foundations Ink Gold 56 Atlanta Hawks 5 Kevin Willis Game Jerseys Autographs 1 Atlanta Hawks 35 Kevin Willis Game Jerseys Autographs Prime 1 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kevin Willis Top-Notch Autographs 4 Atlanta Hawks 25 Kevin Willis Top-Notch Autographs Gold 4 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Digs and Sigs 10 Atlanta Hawks 15 Kyle Korver Digs and Sigs Prime 10 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Foundations Ink 23 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Foundations Ink Gold 23 Atlanta Hawks 5 Pero Antic Main Exhibit Signatures Rookies 43 Atlanta Hawks 299 Spud Webb Main Exhibit Signatures 2 Atlanta Hawks 75 Steve Smith Game Jerseys Autographs 3 Atlanta Hawks 199 Steve Smith Game Jerseys Autographs Prime 3 Atlanta Hawks 25 Steve Smith Top-Notch Autographs 31 Atlanta Hawks 325 Steve Smith Top-Notch Autographs Gold 31 Atlanta Hawks 25 groupbreakchecklists.com 13/14 Innovation Basketball Player Set Card # Team Print Run Bill Sharman Top-Notch Autographs -

Rosters Set for 2014-15 Nba Regular Season

ROSTERS SET FOR 2014-15 NBA REGULAR SEASON NEW YORK, Oct. 27, 2014 – Following are the opening day rosters for Kia NBA Tip-Off ‘14. The season begins Tuesday with three games: ATLANTA BOSTON BROOKLYN CHARLOTTE CHICAGO Pero Antic Brandon Bass Alan Anderson Bismack Biyombo Cameron Bairstow Kent Bazemore Avery Bradley Bojan Bogdanovic PJ Hairston Aaron Brooks DeMarre Carroll Jeff Green Kevin Garnett Gerald Henderson Mike Dunleavy Al Horford Kelly Olynyk Jorge Gutierrez Al Jefferson Pau Gasol John Jenkins Phil Pressey Jarrett Jack Michael Kidd-Gilchrist Taj Gibson Shelvin Mack Rajon Rondo Joe Johnson Jason Maxiell Kirk Hinrich Paul Millsap Marcus Smart Jerome Jordan Gary Neal Doug McDermott Mike Muscala Jared Sullinger Sergey Karasev Jannero Pargo Nikola Mirotic Adreian Payne Marcus Thornton Andrei Kirilenko Brian Roberts Nazr Mohammed Dennis Schroder Evan Turner Brook Lopez Lance Stephenson E'Twaun Moore Mike Scott Gerald Wallace Mason Plumlee Kemba Walker Joakim Noah Thabo Sefolosha James Young Mirza Teletovic Marvin Williams Derrick Rose Jeff Teague Tyler Zeller Deron Williams Cody Zeller Tony Snell INACTIVE LIST Elton Brand Vitor Faverani Markel Brown Jeffery Taylor Jimmy Butler Kyle Korver Dwight Powell Cory Jefferson Noah Vonleh CLEVELAND DALLAS DENVER DETROIT GOLDEN STATE Matthew Dellavedova Al-Farouq Aminu Arron Afflalo Joel Anthony Leandro Barbosa Joe Harris Tyson Chandler Darrell Arthur D.J. Augustin Harrison Barnes Brendan Haywood Jae Crowder Wilson Chandler Caron Butler Andrew Bogut Kentavious Caldwell- Kyrie Irving Monta Ellis -

Jim Mccormick's Points Positional Tiers

Jim McCormick's Points Positional Tiers PG SG SF PF C TIER 1 TIER 1 TIER 1 TIER 1 TIER 1 Russell Westbrook James Harden Giannis Antetokounmpo Anthony Davis Karl-Anthony Towns Stephen Curry Kevin Durant DeMarcus Cousins John Wall LeBron James Rudy Gobert Chris Paul Kawhi Leonard Nikola Jokic TIER 2 TIER 2 TIER 2 TIER 2 TIER 2 Kyrie Irving Jimmy Butler Paul George Myles Turner Hassan Whiteside Damian Lillard Gordon Hayward Blake Griffin DeAndre Jordan Draymond Green Andre Drummond TIER 3 TIER 3 TIER 3 TIER 3 TIER 3 Kemba Walker CJ McCollum Khris Middleton Paul Millsap Joel Embiid Kyle Lowry Bradley Beal Kevin Love Al Horford Dennis Schroder Klay Thompson LaMarcus Aldridge Marc Gasol DeMar DeRozan Kirstaps Porzingis Nikola Vucevic TIER 4 TIER 4 TIER 4 TIER 4 TIER 4 Jrue Holiday Andrew Wiggins Otto Porter Jr. Julius Randle Dwight Howard Mike Conley Devin Booker Carmelo Anthony Jusuf Nurkic Jeff Teague Brook Lopez Eric Bledsoe TIER 5 TIER 5 TIER 5 TIER 5 TIER 5 Goran Dragic Victor Oladipo Harrison Barnes Ben Simmons Clint Capela Ricky Rubio Avery Bradley Robert Covington Serge Ibaka Jonas Valanciunas Elfrid Payton Gary Harris Jae Crowder Steven Adams TIER 6 TIER 6 TIER 6 TIER 6 TIER 6 D'Angelo Russell Evan Fournier Tobias Harris Aaron Gordon Willy Hernangomez Isaiah Thomas Wilson Chandler Derrick Favors Enes Kanter Dennis Smith Jr. Danilo Gallinari Markieff Morris Marcin Gortat Lonzo Ball Trevor Ariza Gorgui Dieng Nerlens Noel Rajon Rondo James Johnson Marcus Morris Pau Gasol George Hill Nicolas Batum Dario Saric Greg Monroe Patrick Beverley -

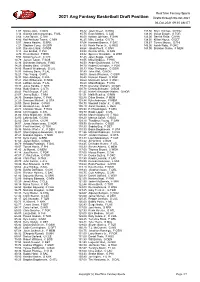

2020 Avg Fantasy Basketball Draft Position

RealTime Fantasy Sports 2021 Avg Fantasy Basketball Draft Position Drafts through 03-Oct-2021 04-Oct-2021 09:35 AM ET 1.07 Nikola Jokic, C DEN 85.42 Jalen Green, G HOU 137.50 Khyri Thomas, G HOU 3.14 Giannis Antetokounmpo, F MIL 85.75 Evan Mobley, C CLE 138.00 Goran Dragic, G TOR 3.64 Luka Doncic, G DAL 86.00 Keldon Johnson, F SAN 138.00 Derrick Rose, G NYK 4.86 Karl-Anthony Towns, C MIN 86.25 Mike Conley, G UTA 138.50 Killian Hayes, G DET 5.57 James Harden, G BRK 87.64 Harrison Barnes, F SAC 139.67 Tyrese Maxey, G PHI 7.21 Stephen Curry, G GSW 87.83 Kevin Porter Jr., G HOU 143.00 Isaiah Roby, F OKC 8.93 Damian Lillard, G POR 88.64 Jakob Poeltl, C SAN 143.00 Brandon Clarke, F MEM 9.14 Joel Embiid, C PHI 89.58 Derrick White, G SAN 9.79 Kevin Durant, F BRK 89.82 Spencer Dinwiddie, G WSH 9.93 Nikola Vucevic, C CHI 92.45 Jalen Suggs, G ORL 10.79 Jayson Tatum, F BOS 93.55 Mikal Bridges, F PHX 12.36 Domantas Sabonis, F IND 94.50 Andre Drummond, C PHI 14.29 Bradley Beal, G WSH 94.70 Robert Covington, F POR 14.86 Russell Westbrook, G LAL 95.33 Klay Thompson, G GSW 14.93 Anthony Davis, F LAL 97.89 John Wall, G HOU 16.21 Trae Young, G ATL 98.00 James Wiseman, C GSW 16.93 Bam Adebayo, F MIA 98.40 Norman Powell, G POR 17.21 Zion Williamson, F NOR 98.60 Montrezl Harrell, F WSH 19.43 LeBron James, F LAL 98.60 Miles Bridges, F CHA 19.43 Julius Randle, F NYK 99.40 Devonte' Graham, G NOR 19.64 Rudy Gobert, C UTA 100.78 Dennis Schroder, G BOS 20.43 Paul George, F LAC 101.45 Nickeil Alexander-Walker, G NOR 23.07 Jimmy Butler, F MIA 101.91 Malik Beasley, -

Nba Legacy -- Dana Spread

2019-202018-19 • HISTORY NBA LEGACY -- DANA SPREAD 144 2019-20 • HISTORY THIS IS CAROLINA BASKETBALL 145 2019-20 • HISTORY NBA PIPELINE --- DANA SPREAD 146 2019-20 • HISTORY TAR HEELS IN THE NBA DRAFT 147 2019-20 • HISTORY BARNES 148 2019-20 • HISTORY BRADLEY 149 2019-20 • HISTORY BULLOCK 150 2019-20 • HISTORY VC 151 2019-20 • HISTORY ED DAVIS 152 2019-20 • HISTORY ellington 153 2019-20 • HISTORY FELTON 154 2019-20 • HISTORY DG 155 2019-20 • HISTORY henson (hicks?) 156 2019-20 • HISTORY JJACKSON 157 2019-20 • HISTORY CAM JOHNSON 158 2019-20 • HISTORY NASSIR 159 2019-20 • HISTORY THEO 160 2019-20 • HISTORY COBY WHITE 161 2019-20 • HISTORY MARVIN WILLIAMS 162 2019-20 • HISTORY ALL-TIME PRO ROSTER TAR HEELS WITH NBA CHAMPIONSHIP RINGS Name Affiliation Season Team Billy Cunningham (1) Player 1966-67 Philadelphia 76ers Charles Scott (1) Player 1975-76 Boston Celtics Mitch Kupchak Player 1977-78 Washington Bullets Tommy LaGarde (1) Player 1978-79 Seattle SuperSonics Mitch Kupchak Player 1981-82 Los Angeles Lakers Bob McAdoo Player 1981-82 Los Angeles Lakers Bobby Jones (1) Player 1982-83 Philadelphia 76ers Mitch Kupchak (3) Player 1984-85 Los Angeles Lakers Bob McAdoo (2) Player 1984-85 Los Angeles Lakers James Worthy Player 1984-85 Los Angeles Lakers James Worthy Player 1986-87 Los Angeles Lakers James Worthy (3) Player 1987-88 Los Angeles Lakers Michael Jordan Player 1990-91 Chicago Bulls Scott Williams Player 1990-91 Chicago Bulls Michael Jordan Player 1991-92 Chicago Bulls Scott Williams Player 1991-92 Chicago Bulls Michael Jordan Player -

2020-21 Schedule (8-4, 3-2 Acc) Statistical Comparison

GAME 13: at Florida State Saturday, Jan. 16, 2021 Tucker Center Tallahassee, Fla. Noon – ESPN 2020-21 SCHEDULE (8-4, 3-2 ACC) 7 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS: NCAA 1957, 1982, 1993, 2005, 2009, 2017; Helms 1924 (4-0 Home, 1-3 Away, 3-1 Neutral) 20 FINAL FOURS 50 NCAA TOURNAMENT APPEARANCES NOVEMBER (AP rankings) 32 ACC REGULAR-SEASON CHAMPIONSHIPS 25 College of Charleston (16/-) W, 79-60 ACCN 30 vs. UNLV & (14/-) W, 78-51 ESPN2 18 ACC TOURNAMENT CHAMPIONSHIPS 38 TIMES IN THE FINAL ASSOCIATED PRESS TOP-10 RANKINGS DECEMBER 1 vs. Stanford & (14/-) W, 67-63 ESPN GAME 13 2 vs. Texas & (14/17) L, 67-69 ESPN STATISTICAL COMPARISON • The Tar Heels play their fourth ACC road 8 at Iowa # (16/3) L, 80-93 ESPN UNC FSU 12 NC Central (16/-) W, 73-67 RSN game of the season when they travel to Talla- Record 8-4, 3-2 6-2, 2-1 19 vs. Kentucky ! (22/-) W, 75-63 CBS hassee, Fla., on Saturday, January 16 to play Points/Game 73.0 78.8 22 at NC State (17/-) L, 76-79 ACCN Florida State. Scoring Defense 68.5 69.0 30 at Georgia Tech (-/-) L, 67-72 RSN • Carolina has won three in a row and is 8-4 Scoring Margin +4.5 +9.8 overall, 3-2 in the ACC. FG% .417 .466 JANUARY • UNC is 1-2 in ACC road games this season, 2 Notre Dame (-/-) W, 66-65 ACCN 3FG% .293 .372 5 at Miami (-/-) W, 67-65 ESPN winning by two points at Miami and losing by 3FGs/Game 5.1 8.5 12 Syracuse (-/-) W, 81-75 ACCN three at NC State and five at Georgia Tech.