An Analytical Study of South African Prison Reform After 1994

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intergovernmental Relations Policy Framework

INTERGOVERNMENTAL AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS 1 POLICY : INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS POLICY FRAMEWORK Item CL 285/2002 PROPOSED INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS POLICY FRAMEWORK MC 05.12.2002 RESOLVED: 1. That the report of the Strategic Executive Director: City Development Services regarding a proposed framework to ensure sound intergovernmental relations between the EMM, National and Provincial Government, neighbouring municipalities, the S A Cities Network, organised local government and bulk service providers, BE NOTED AND ACCEPTED. 2. That all Departments/Portfolios of the EMM USE the Intergovernmental Relations Policy Framework to develop and implement mechanisms, processes and procedures to ensure sound intergovernmental relations and TO SUBMIT a policy and programme in this regard to the Speaker for purposes of co-ordination and approval by the Mayoral Committee. 3. That the Director: Communications and Marketing DEVELOP a policy on how to deal with intergovernmental delegations visiting the Metro, with specific reference to intergovernmental relations and to submit same to the Mayoral Committee for consideration. 4. That intergovernmental relations BE INCORPORATED as a key activity in the lOP Business Plans of all Departments of the EMM. 5. That the Ekurhuleni Intergovernmental Multipurpose Centre Steering Committee INCORPORATE the principles contained in the Intergovernmental Relations Framework as part of the policy on multipurpose centres to be formulated as contemplated in Mayoral Committee Resolution (Item LED 21-2002) of 3 October 2002. 6. That the City Manager, in consultation with the Strategic Executive Director: City Development Services, FINALISE AND APPROVE the officials to represent the EMM at the Technical Working Groups of the S A Cities Network. 7. That the Strategic Executive Director: City Development SUBMIT a further report to the Mayoral Committee regarding the necessity of participation of the Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality and its Portfolios/Departments on public bodies, institutions and organisations. -

Thematic Report on Criminal Justice and Human Rights In

THEMATIC REPORT ON CRIMINAL JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN SOUTH AFRICA A Submission to the UN Human Rights Committee in response to the Initial Report by South Africa under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights at the 116th session of the Human Rights Committee (Geneva March 2016) By the following organisations : Civil Society Prison Reform Initiative Just Detention International Lawyers for Human Rights NICRO 1 Contents Executive summary ................................................................................................................................. 3 Contact details of contributing organisations .......................................................................................... 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 7 Methodology and limitations .................................................................................................................. 8 Arbitrary arrest and detention ................................................................................................................. 8 Arrest without a warrant ..................................................................................................................... 8 Pre-trial detention .............................................................................................................................. 10 Delays in bail applications ................................................................................................................... -

State Capture and the Political Manipulation of Criminal Justice Agencies a Joint Submission to the Judicial Commission of Inquiry Into Allegations of State Capture

State capture and the political manipulation of criminal justice agencies A joint submission to the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture CORRUPTION WATCH AND THE INSTITUTE FOR SECURITY STUDIES APRIL 2019 State capture and the political manipulation of criminal justice agencies A joint submission by Corruption Watch and the Institute for Security Studies to the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture April 2019 Contents Executive summary ..........................................................................................................................................3 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................3 Structure and purpose of this submission .....................................................................................................3 Impact of manipulation of criminal justice agencies .......................................................................................4 Recent positive developments .......................................................................................................................4 Recommendations ........................................................................................................................................4 Fixing the legacy of the manipulation of criminal justice agencies..............................................................4 Addressing risk factors for future manipulation -

Restorative Justice Programmes in a Prison Environment: a Qualitative Enquiry

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE PROGRAMMES IN A PRISON ENVIRONMENT: A QUALITATIVE ENQUIRY BY CLARICE ZIMBILI ZONDI, MA (UNIZUL) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Department of Criminal Justice University of Zululand Promoter: Prof. J.M. Ras Date of submission: April 2014 DECLARATION I declare that the thesis “Restorative Justice programmes in a prison environment: A qualitative enquiry”, is my own work both in conception and in execution. As far as possible and where applicable, I have acknowledged all my sources by means of complete references. …………………………………………… MISS. C. Z. ZONDI (Student nr. 840710) i DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my grandson Loyiso and his parents Ayanda and Kutele Mabude for their love and support in my academic endeavours. Soli Deo Gloria! ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere gratitude to the following persons and institutions for their assistance: The Lord my Saviour, without His intervention this study was not possible. I have always depended on Him and He has never let me down. To Him be the glory. My promoter, Prof. J. M. Ras for his inspiration, guidance, understanding and never ending support. Baie dankie Prof. Phoenix Zululand, with special reference to Richard Aitken and Nonceba Lushaba for providing information regarding their restorative justice programmes. DCS officials who have contributed to this research in one or other way. DCS Regional Office in Pietermaritzburg for providing statistical information on the prisons. Friends and family who have supported me during this study. My late mother, Kessiah Zondi, who always proudly had enjoyed every step that I take towards reaching my dream of completing the thesis FACASA staff for their assistance during this study. -

Prisons – a Call to Action for Post-Apartheid Administrative Lawyers Keynote by Justice Edwin Cameron

Administrative Justice Association of South Africa AGM Thursday 4 March 2021, 18h00 Prisons – A call to action for post-apartheid administrative lawyers Keynote By Justice Edwin Cameron • Introduction 1. It is a pleasure and an honour to address your Annual General Meeting. My chosen topic is prisons. This is not only because, for the last fourteen months I’ve been Inspecting Judge of Prisons. It’s also because the very concept of prisons is arrestingly forbidding, even alarming – and rightly so. Mass confinement of mostly adult males is a relatively recent phenomenon, about two centuries old.1 It has overtones of horror which future generations may look back on with moral censure. 2. In South Africa, there is an additional concern – that, as under apartheid, our prisons are becoming dark, closed and punitive institutions. 3. The concept of prisons and our prisons practice in South Africa urgently need attention from public interest lawyers and academics. Yet public debate about prisons and the utility of our sentencing regime is conspicuously lacking. 4. Why do we turn our gaze away from the evident problems? Where, in particular, are the administrative lawyers? What role can they play? 5. There are some legitimate reasons. 1 Other punitive methods, including execution, were used. And from 1788 to 1868, about 162 000 convicts were transported from Britain and Ireland to Australia. The British Government first transported convicts to American colonies in the early 18th century. See archives from the Australian Government “Convicts and the British Colonies in Australia” available at https://web.archive.org/web/20160101181100/http://www.australia.gov.au/about- australia/australian-story/convicts-and-the-british-colonies (accessed 5 March 2021). -

The Anti-Apartheid Movements in Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand

The anti-apartheid movements in Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand By Peter Limb Introduction The history of the anti-apartheid movement(s) (AAM) in Aotearoa/New Zealand and Australia is one of multi-faceted solidarity action with strong international, but also regional and historical dimensions that gave it specific features, most notably the role of sports sanctions and the relationship of indigenous peoples’ struggles to the AAM. Most writings on the movement in Australia are in the form of memoirs, though Christine Jennett in 1989 produced an analysis of it as a social movement. New Zealand too has insightful memoirs and fine studies of the divisive 1981 rugby tour. The movement’s internal history is less known. This chapter is the first history of the movement in both countries. It explains the movement’s nature, details its history, and discusses its significance and lessons.1 The movement was a complex mosaic of bodies of diverse forms: there was never a singular, centralised organisation. Components included specific anti-apartheid groups, some of them loose coalitions, others tightly focused, and broader supportive organisations such as unions, churches and NGOs. If activists came largely from left- wing, union, student, church and South African communities, supporters came from a broader social range. The liberation movement was connected organically not only through politics, but also via the presence of South Africans, prominent in Australia, if rather less so in New Zealand. The political configuration of each country influenced choice of alliance and depth of interrelationships. Forms of struggle varied over time and place. There were internal contradictions and divisive issues, and questions around tactics, armed struggle and sanctions, and how to relate to internal racism. -

South African Crime Quarterly, No 48

CQ Cover June 2014 7/10/14 3:27 PM Page 1 Reviewing 20 years of criminal justice in South Africa South A f r i c a n CRIME QUA RT E R LY No. 48 | June 2014 Previous issues Stacy Moreland analyses judgements in rape ISS Pretoria cases in the We s t e r n Cape, finding that Block C, Brooklyn Court p a t r i a rchal notions of gender still inform 361 Veale Street judgements in rape case. Heidi Barnes writes a New Muckleneuk case note on the Constitutional Court case Pretoria, South Africa F v Minister of Safety and Security. Alexander Tel: +27 12 346 9500 Hiropoulos and Jeremy Porter demonstrate how Fax:+27 12 460 0998 Geographic Information Systems can be used, [email protected] along with crime pattern theory, to analyse police crime data. Geoff Harris, Crispin Hemson ISS Addis Ababa & Sylvia Kaye report on a conference held in 5th Floor, Get House Building Durban in mid-2013 about measures to reduce Africa Avenue violence in schools; and Hema Harg o v a n Addis Ababa, Ethiopia reviews the latetest edition of Victimology in Tel: +251 11 515 6320 South Africa by Robert Peacock (ed). Fax: +251 11 515 6449 [email protected] Andrew Faull responds to Herrick and Charman ISS Dakar (SACQ 45), delving into the daily liquor policing 4th Floor, Immeuble Atryum in the Western Cape. He looks beyond policing Route de Ouakam for solutions to alcohol-related harms. Claudia Forester-Towne considers how race and gender Dakar, Senegal influence police reservists' views about their Tel: +221 33 860 3304/42 work. -

Apartheid South Africa Xolela Mangcu 105 5 the State of Local Government: Third-Generation Issues Doreen Atkinson 118

ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p State of the Nation South Africa 2003–2004 Free download from www.hsrc Edited by John Daniel, Adam Habib & Roger Southall ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Free download from www.hsrc ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Compiled by the Democracy & Governance Research Programme, Human Sciences Research Council Published by HSRC Press Private Bag X9182, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa HSRC Press is an imprint of the Human Sciences Research Council Free download from www.hsrc ©2003 Human Sciences Research Council First published 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. ISBN 0 7969 2024 9 Cover photograph by Yassir Booley Production by comPress Printed by Creda Communications Distributed in South Africa by Blue Weaver Marketing and Distribution, PO Box 30370, Tokai, Cape Town, South Africa, 7966. Tel/Fax: (021) 701-7302, email: [email protected]. Contents List of tables v List of figures vii ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Acronyms ix Preface xiii Glenn Moss Introduction Adam Habib, John Daniel and Roger Southall 1 PART I: POLITICS 1 The state of the state: Contestation and race re-assertion in a neoliberal terrain Gerhard Maré 25 2 The state of party politics: Struggles within the Tripartite Alliance and the decline of opposition Free download from www.hsrc Roger Southall 53 3 An imperfect past: -

Between Ramaphosa's New Dawn And

Between Ramaphosa’s New Dawn and Zuma’s Long Shadow: Will the Centre hold? Ashwin Desai Abstract Cyril Ramaphosa was sworn in as South Africa’s President in February 2018 after the late-night resignation of Jacob Zuma. His ascendency came in the wake of a bruising battle with Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma that saw him become head of the African National Congress (ANC) by the narrowest of margins. Ramaphosa promised a new dawn that would sweep aside the allegations of the looting of state resources under the Zuma Presidency and restore faith in the criminal justice system. This article firstly looks at the impact that the Zuma presidency has had on South African politics against the backdrop of the Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki years. The article then focuses on Ramaphosa’s coming to power and what this holds for pushing back corruption and addressing the seemingly intractable economic challenges. In this context, I use Gramsci’s ideas of the war of manoeuvre and war of position to provide an understanding of the limits and possibilities of the Ramaphosa presidency. The analysis presented is a conjunctural analysis that as Gramsci points out focusses on ‘political criticism of a day-to-day character, which has as its subject top political leaders and personalities with direct governmental responsibilities’ as opposed to organic developments that lend itself to an understanding of durable dilemmas and ‘give rise to socio-historical criticism, whose subject is wider social groupings – beyond the public figures and beyond the top leaders’ (quoted in Morton 1997: 181). Keywords: Zuma, Ramaphosa, Black Economic Empowerment, State Capture Alternation 26,1 (2019) 214 - 238 214 Print ISSN 1023-1757; Electronic ISSN: 2519-5476; DOI https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2019/v26n1a10 Between Ramaphosa’s New Dawn and Zuma’s Long Shadow Introduction I was in the crowd in 1994 as the Oryx beat by, the bright flag of a new South Africa fluttering beneath. -

November 2009.Pdf

Project of the Community Law Centre CSPRI "30 Days/Dae/Izinsuku" CSPRI "30 Days/Dae/Izinsuku" November 2009 November 2009 In this Issue: CORRUPTION AND GOVERNANCE SENTENCING AND PAROLE SAFETY AND SECURITY HEALTH OTHER AFRICAN COUNTRIES Top of Page CORRUPTION AND GOVERNANCE Prison officers suspended: A report in News24 said that the Western Cape Correctional Services security chief, Lionel Adams and another senior official have been suspended after an unauthorised release of a prisoner. The Department's spokesperson, Ofentse Morwane, confirmed that Adams and Julius Mentoor of the Cape Town Community Corrections office were suspended on full pay following the release of a prisoner from the Goodwood correctional centre. SAPA, 11 November 2009, News24, at http://www.news24.com/Content/SouthAfrica/News/1059/0df6455b566b488c8d0b2b8abd6fae34/11-11- 2009-07-02/Cape_prison_bosses_suspended Lack of accountability at Correctional Services: The Minister of Correctional Services, Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula, lamented the lack of accountability and non-compliance that is deeply engrained in her ministry. While briefing Parliament's Portfolio Committee on Correctional Services, the Minister said "The truth of the matter is that the organisational culture in the Department of Correctional Services, is (that) of non-accountability", adding that "The lines of accountability in [her] view are very blurred." News24 Reported. SAPA, 17 November 2009, New24 at http://www.news24.com/Content/SouthAfrica/News/1059/3fcf01e25e3d4dcea46ff23422a9ca2f/11-11- 2009-05-03/Prisons_not_accountable MPs get report on prison fraud: A report from IOL stated that the Special Investigations Unit (SIU) has briefed Members of Paliament(MPs) on an alleged prison graft at the Department of Correctional Services. -

Table of Contents

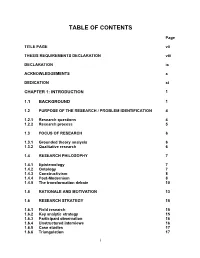

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TITLE PAGE vii THESIS REQUIREMENTS DECLARATION viii DECLARATION ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS x DEDICATION xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE RESEARCH / PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION 4 1.2.1 Research questions 4 1.2.2 Research process 5 1.3 FOCUS OF RESEARCH 6 1.3.1 Grounded theory analysis 6 1.3.2 Qualitative research 6 1.4 RESEARCH PHILOSOPHY 7 1.4.1 Epistemology 7 1.4.2 Ontology 7 1.4.3 Constructivism 8 1.4.4 Post-Modernism 8 1.4.5 The transformation debate 10 1.5 RATIONALE AND MOTIVATION 13 1.6 RESEARCH STRATEGY 15 1.6.1 Field research 15 1.6.2 Key analytic strategy 15 1.6.3 Participant observation 16 1.6.4 Unstructured interviews 16 1.6.5 Case studies 17 1.6.6 Triangulation 17 i 1.6.7 Purposive sampling 17 1.6.8 Data gathering and data analysis 18 1.6.9 Value of the research and potential outcomes 18 1.6.10 The researcher's background 19 1.6.11 Chapter layout 19 CHAPTER 2: CREATING CONTEXT: SPORT AND DEMOCRACY 21 2.1 INTRODUCTION 21 2.2 SPORT 21 2.2.1 Conceptual clarification 21 2.2.2 Background and historical perspective 26 2.2.2.1 Sport in ancient Rome 28 2.2.2.2 Sport and the English monarchy 28 2.2.2.3 Sport as an instrument of politics 29 2.2.3 Different viewpoints 30 2.2.4 Politics 32 2.2.5 A critical overview of the relationship between sport and politics 33 2.2.5.1 Democracy 35 (a) Defining democracy 35 (b) The confusing nature of democracy 38 (c) Reflection on democracy 39 2.3 CONCLUSION 40 CHAPTER 3: SPORT IN A GLOBAL CONTEXT 42 3.1 INTRODUCTION 42 3.2 A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE OF SPORT 43 -

Human Rights and Mental Health in Post-Apartheid South Africa

Bantjes et al. BMC International Health and Human Rights (2017) 17:29 DOI 10.1186/s12914-017-0136-0 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Human rights and mental health in post-apartheid South Africa: lessons from health care professionals working with suicidal inmates in the prison system Jason Bantjes* , Leslie Swartz and Pieter Niewoudt Abstract Background: During the era of apartheid in South Africa, a number of mental health professionals were vocal about the need for socio-economic and political reform. They described the deleterious psychological and social impact of the oppressive and discriminatory Nationalist state policies. However, they remained optimistic that democracy would usher in positive changes. In this article, we consider how mental health professionals working in post-apartheid South Africa experience their work. Methods: Our aim was to describe the experience of mental health professionals working in prisons who provide care to suicidal prisoners. Data were collected from in-depth semi-structured interviews and were analyzed using thematic content analysis. Results: Findings draw attention to the challenges mental health professionals in post-apartheid South Africa face when attempting to provide psychological care in settings where resources are scarce and where the environment is anti-therapeutic. Findings highlight the significant gap between current policies, which protect prisoners’ human rights, and every-day practices within prisons. Conclusions: The findings imply that there is still an urgent need for activism in