Wine Investment in South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISTRICT SAFETY PLAN Overberg

DISTRICT SAFETY PLAN Overberg Civic Centre NR Arendse 15 October 2019 George Introduction – DSPs and the Western Cape Road Safety Situation Average around 1,400 people killed on Western Cape roads each year: • Average 3 to 4 people killed per day. • Estimated 17 people seriously injured per day. Estimated 57 people injured per day (CSIR estimates). • Based on CSIR cost of crashes study, approximate economic burden in WC is R26,937,398 per day. Over R9b per annum • Most of the cost is in loss of earnings – so hits local economies the hardest Caledon “District Safety Plan” (DSP) pilot launched October 2016. Twelve months after implementation: 29.7% reduction in fatalities in the region. © Western Cape Government 2012 | Background Recognizing that the existing crash levels on our roads represent a major impediment to the socio-economic development of the Western Cape, the Transport Branch of the Department of Transport & Public Works has adopted a vision of zero fatalities and serious injuries on Western Cape roads. Together with its partners in all three spheres of government, the Branch has conducted a process to develop a District Safety Plan in the Caledon Traffic Centre area of operations. © Western Cape Government 2012 | Go to Insert > Header & Footer > Enter presentation name into footer field 3 Background © Western Cape Government 2012 | Go to Insert > Header & Footer > Enter presentation name into footer field 4 Vision Zero and the Safe System Jurisdictions where “safe system” road safety strategies have been adopted which include targets of ZERO fatalities and/or serious injuries: Sweden Northern Ireland Edmonton; Canada London, Bristol, Brighton, Blackpool; UK New York, Boston, Los Angeles, Washington, Seattle, Austin etc; USA Mexico City; Mexico © Western Cape Government 2012 | Go to Insert > Header & Footer > Enter presentation name into footer field 5 Vision Zero and the Safe System No-one should be killed or seriously injured while using the road network. -

Coaxial Connectors Navigator the ABC’S of Ordering from Radiall A

Coaxial Connectors Navigator The ABC’s of Ordering From Radiall A. Series P/N Series Prefix Radiall and Radiall AEP Orientation Gender Connector Catalog P/N & Part Number Series 3 digits correspond to series Radiall AEP Part 4 digits correspond to series (SMA, BNC, SMB, etc; refer to (SMA, BNC, SMB, etc.; refer to Section Number Straight Male Prefix Radiall System Number System Interface finder guide for series) finder guide for series) Name R XXX XXX XXX 3 digits correspond to function 9000-XXXX-XXX 4 digits correspond to function (Plating, captivation, attachment (Interface, geometry, panel Body mounting, etc.) and materials) Right angle Female 3 digits correspond to variant 3 digits correspond to variant Size (Variation) (Dimension, finish, packaging, etc.) Attachment B. Style C. Electrical Options Coupling System Main Cable Types SMA, SMC, TNC, N, UMP, MMS, MMT, BMA, SMP QMA, QN, SMB "Fakra Ω UHF, DIN 7/16, etc. MC-Card, SMB, MCX "smooth bore" BNC, C and USCar,"SMZ type 43 IMP, UMP Performance: Performance: Performance: Performance: Performance: Performance: Excellent Average Excellent Average Average Average Connection time: Connection time: Connection time: Connection time: Lock Connection time: Connection time: Bayonet Snap-On Slide-On Long Very fast Very fast Fast Very fast Press-On Very fast Screw-On Minimum Frequency Needs space Space saving Space saving Needs space Space saving Space saving Mating Cycles Measured in GHz: current Perfect for Outer latching Secured mating Perfect for Durability range is DC-40 GHz (Max) miniaturization -

Parapro Assessment Information Bulletin (PDF)

ParaPro Assessment Information Bulletin 2021–22 The policies and procedures explained in this Bulletin are effective only for the 2021–22 testing year (August 1, 2021 through July 31, 2022) and supersede previous policies and procedures. The fees, terms and conditions contained in this Bulletin are subject to change. Educational Testing Service is dedicated to the principle of equal opportunity, and its programs, services and employment policies are guided by that principle. Copyright © 2021 by ETS. All rights reserved. ETS, the ETS logo and PRAXIS are registered trademarks of ETS. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. 2021–22 ParaPro Assessment Bulletin 2 www.ets.org/parapro Contents ParaPro at a Glance .......................................................... 4 File Corrections ........................................................13 Registration .................................................................4 Test Retake Policy .....................................................13 Test Takers with Disabilities or Health-related Acknowledgment and Data Retention ................13 Needs ............................................................................4 Acknowledgment .............................................................. 13 Test Preparation Material .........................................4 Personal Information ........................................................ 13 On Test Day ..................................................................5 How We Use Your Personal Information -

National Road N12 Section 6: Victoria West to Britstown

STAATSKOERANT, 15 OKTOBER 2010 NO.33630 3 GOVERNMENT NOTICE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORT No. 904 15 October 2010 THE SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL ROADS AGENCY LIMITED Registration No: 98109584106 DECLARATION AMENDMENT OF NATIONAL ROAD N12 SECTION 6 AMENDMENT OF DECLARATION No. 631 OF 2005 By virtue of section 40(1)(b) of the South African National Roads Agency Limited and the National Roads Act, 1998 (Act NO.7 of 1998), I hereby amend Declaration No. 631 of 2005, by substituting the descriptive section of the route from Victoria West up to Britstown, with the subjoined sheets 1 to 27 of Plan No. P727/08. (National Road N12 Section 6: Victoria West - Britstown) VI ~/ o8 ~I ~ ~ ... ... CD +' +' f->< >< >< lli.S..E..I VICTORIA WEST / Ul ~ '-l Ul ;Ii; o o -// m y 250 »JJ z _-i ERF 2614 U1 iii,..:.. "- \D o lL. C\J a Q:: lL. _<n lLJ ~ Q:: OJ olLJ lL. m ~ Q:: Q) lLJ JJ N12/5 lL. ~ fj- Q:: ~ I\J a DECLARATION VICTORIA lLJ ... ... .... PLAN No. P745/09 +' a REM 550 +' :£ >< y -/7 0 >< WEST >< 25 Vel von stel die podreserwe voor von 'n gedeelte Z Die Suid Afrikoonse Nosionole Podogentskop 8eperk Die figuur getoon Sheet 1 of 27 a represents the rood reserve of 0 portion ~:~:~:~: ~ :~: ~:~:~:~:~:~ The figure shown w The South African Notional Roods Agency Limited ........... von Nosionole Roete Seksie 6 Plan w :.:-:-:-:.:.:-:.:-:-:.: N12 OJ of Notional Route Section P727108 w a D.O.9.A • U1 01 o II') g 01' ICTORIA0' z " o o (i: WEST \V II> ..... REM ERF 9~5 II') w ... -

PRICING 2016 .Xlsx

Retail Wholesale Price Bulk Fabric Composition Width GSM Available Colours Price 10-19m 20-90m Price 90-200m Additional Info Hand spun hand woven cotton - 1 SMOOTH 100% cotton 97cm 50 Natural MOQ 25m R265 R235 ± 4- 8 % shrinkage 2 Hand spun hand woven cotton - LACEY 100% cotton 100cm 50 Natural MOQ 25m R215 R195 ± 4- 8 % shrinkage 3 Hand spun hand woven cotton VEIL 100% cotton 80cm 18 Natural MOQ 25m R215 R195 ± 4- 8 % shrinkage 4 Hand spun hand woven cotton - PLAIN 100% cotton 101cm 65 Grey, White MOQ 25m R265 R235 ± 2- 3 % shrinkage Hand spun hand woven cotton - LOOSE 100% cotton, Manufactured in 5 WEAVE the WC, South Africa 120cm 90 Natural R318 R304 R283 ± 4- 8 % shrinkage 6 Sustainable SATIN 100% Organic Cotton Cupro 100cm 90 White MOQ 25m R342 R318 preshrunk (PFP) ±2 -3% shrinkage 7 Hemp SILK 60% hemp 40% Silk 142cm 168 Natural R529 R479 R420 (PFP) Natural: ±5% shrinkage (PFP) ; 55% Hemp 45% GOTS Certified dyed: pre-shrunk 8. A SUMMER LINEN Organic Cotton 145cm 100 See Colour Chart R322 R308 R286 (PFP) Natural: ±5% shrinkage (PFP) ; 55% Hemp 45% GOTS Certified dyed: pre-shrunk 8. B SUMMER LINEN (WIDE) Organic Cotton 250cm 100 See Colour Chart R607 R580 R540 (PFP) Natural: ±5% shrinkage (PFP) ; 55% Hemp 45% GOTS Certified dyed: pre-shrunk 9. A ORGANIC LINEN Organic Cotton 145cm 190 See Colour Chart R332 R318 R295 (PFP) Natural: ±5% shrinkage (PFP) ; 55% Hemp 45% GOTS Certified dyed: pre-shrunk 9. B ORGANIC LINEN (WIDE) Organic Cotton 250cm 190 See Colour Chart R646 R618 R575 (PFP) Natural: ±5% shrinkage (PFP) ; 55% Hemp 45% GOTS -

Tilney Manor

Tilney Manor Tranquillity amidst a secluded oasis Tilney Manor consists of 3 separate units including 6 large open Suite Features plan suites, each opening onto private verandas overlooking breath-taking views of undulating mountains and plains. • Air conditioning This lush oasis setting of Tilney Manor is surrounded by • International dial telephone carefully laid out indigenous gardens. • Tea and coffee making facilities • His and her outdoor showers Lodge Facilities • En-suite bathroom with shower, twin basins and free- standing bath in the centre • Rim-flow swimming pool • Private minibar • Relaxation Retreat with steam room and sauna • Electronic safe • Lounge with fire place and television with satellite channels • Fireplace • Perimeter electric fence • Private veranda • In and outdoor dining facilities • Wi-Fi Suite Configuration All suites can sleep a maximum of 2 adults per suite • 3 King bedded Luxury Suites • 3 Twin bedded Luxury Suites www.sanbona.com | [email protected] | T: +27 (0) 21 010 0028 | F: +27 (0) 86 764 6207 Program of Events The following times are only an indication and approximate as Departing Guests these may vary according to seasons and weather conditions. Lodges operate independently, each with a full staff compliment Pick-up from Dwyka Lodge at 11h00 including its own management team, chef brigade, hosts Pick-up from Gondwana Lodge at 11h20 and hostesses and experienced field guides. Dinner alternates Pick-up from Tilney Manor at 11h35 between the in and outdoor facilities, weather permitting. - arrive at the welcome lounge 12h15 We do suggest that guests arrive in time for lunch on their PLEASE NOTE: All times are estimated and subject to road day of arrival as not to miss out on any game drives during conditions and vehicle types their stay. -

Atlantis Special Economic Zone: Technical Investor Brochure

ATLANTIS SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE: TECHNICAL INVESTOR BROCHURE How to use this guide: This document provides essential technical and other information for potential investors intending to invest in the Atlantis Special Economic Zone. We suggest that you use the index on page two to navigate through the document. In most sections and sub-sections, you will find hyperlinks to useful resources that relate to the topic you are reading about. If you have any queries or feedback about the content of this brochure please contact Jarrod Lyons at GreenCape. 1 1. Overview ................................................................................................... 4 1.1. The Western Cape and Cape Town (general) ..................................... 4 1.2. The Western Cape and City of Cape Town as a green investment destination ....................................................................................................... 5 2. Atlantis and the Atlantis Special Economic Zone (ASEZ) .......................... 8 2.1. About Atlantis ...................................................................................... 8 2.2. The Atlantis Special Economic Zone: An overview.............................. 8 2.3. Why invest in the Atlantis Special Economic Zone? ............................ 9 2.4. Types of industries that can be hosted .............................................. 11 2.5. How to access investor support ......................................................... 11 2.5.1. One-stop-shop for investment support: Cape Investor Centre -

Ministerial Committee on the Review of the Funding Frameworks of TVET Colleges and CET Colleges

Ministerial Committee on the review of the funding frameworks of TVET Colleges and CET colleges Information Report and Appendices for presentation to Minister B.E. Nzimande, M.P. Minister of Higher Education and Training July 2017 Contents Foreword. ................................................................................................................................. xi Executive summary. ..............................................................................................................xiii Abbreviations. ........................................................................................................................ xv A note on the problems and standardisation of terminology. ........................................... xix Acknowledgements. ............................................................................................................xxiii Section 1: The brief .................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1. The Committee, its purpose, tasks and Terms of Reference. ....................... 1 Section 2: The national context and the TVET College and Community Learning Centre systems. ..................................................................... 7 Chapter 2. Economy and education. ................................................................................. 7 Introduction: education and development. ......................................................... 7 Education and economic growth ..................................................................... -

Postal Rates

• 2021/2022 • 2020/2021 Customer Care: 502 0860 111 www.postoffice.co.za CHURE RO BROCHURE B DID YOU 2021 / 2022 ... 1 APR. 21 - 31 MAR. 22 KNOW YOU ARE NOT ALLOWED TO TABLE OF CONTENTS POST THE FOLLOWING GOODS? Dangerous and Prohibited goods 1 Important Information 2 Ordinary Mail / Fast Mail 3-4 Postage Included Envelopes 4-5 Postcards 5 Domestic Stamp Booklets and Rolls 6 Packaging Products 6 Franking Machines 6-7 Domestic Registered Letter with Insurance Option 7-8 Mailroom Management 8 Direct Mail 9 Business Reply Services 9-10 InfoMail 10-12 Response Mail / Magmail 13-14 Domestic Parcel Service 14-15 International Mail 15-20 Expedited Mail Service 21-24 Philatelic Products 25 Postboxes, Private Bags and Accessories 25-26 (Valid 01 Jan to 31 Dec annually) Postbank 26 Speed Services Couriers 27-29 Tips to get your letter delivered on time, every time: 30 Contact Information / Complaints and Queries 31 DID YOU KNOW... YOU ARE NOT ALLOWED TO POST THE FOLLOWING GOODS? DANGEROUS AND PROHIBITED GOODS SCHEDULE OF DANGEROUS GOODS • Explosives – Ammunition, fireworks, igniters. • Compressed Gas – aerosol products, carbon dioxide gas, cigarette lighter, butane. • Flammable Liquids – alcohol, flammable paint thinners, flammable varnish removers, turpentine, petroleum products, benzene. • Flammable Solids – metallic magnesium, matches, zinc powder. • Oxidising material – some adhesives, some bleaching powders, hair or textiles dyes made of organic peroxides, fiberglass repair kits, chlorine. • Poison including Drugs and Medicine –although some are acceptable in prescription quantities, and non-infectious perishable biological substances are accepted when packed and transmitted appropriately RADIOACTIVE MATERIAL • Corrosives – corrosive cleaning liquid, paint or varnish removers, mercury filled thermometer • Miscellaneous – magnetized materials, oiled paper, polymerisable materials SCHEDULE OF PROHIBITED GOODS Bank notes – including all South African notes of whatever issue or denomination, and the bank notes or currency notes of any other country. -

Langeberg Activities 2016

De Doorns DISTANCE TABLE N1 Ashton - Montagu - 9km NOUGASPOORT Ashton - Robertson - 18km N1 2 Ashton - Bonnievale - 16km 3 5 Robertson - McGregor - 20km Worcester Robertson - Bonnievale - 28km 5 4 11 4 1 ROOIHOOGTE PASS 3 R60 BURGERS PASS 1 4 10 19 R318 6 2 ROUTE ACTIVITI ES OU BERG PASS 9 8 1 CAMP SITES Langeberg mountain range 1 1 62ZA GAME & NATURE RESERVES FARM TOURS 6 2 RIVER CRUISES Robertson 4 3 5 1 3 12 2 HIKING TRAILS 2 6 4 2 2 2 6 1 5-8 3 Montagu 1 10 11 5 2 3 1 1 TRACTOR TRIPS 4 2 8 1 1 4 3 6 3 9 18 1 2 20 5 5 7 1 3 2 6 2 2-3 RIVER RAFTING/CANOEING 3 5 2 4 6 7 R60 4 5 17 2 4 8 MOUNTAIN CLIMBING/ 2 2 3 KOGMANS- 1 KINGNA RIVER ABSAILING /KLOOFING 2 BREEDE RIVER R317 5 KLOOF PASS 3 1 SKYDIVING 13 MTB TOURS 1 6 1 FARM STALLS 9 KOGMANS- R60 R62 KLOOF RIVER 8 3 10 FARMER’S MARKETS R290 9 6 OLIVE 2 1 7 6 6 1 3 1 MUSEUMS 7 7 3 7 ROUTE 8 9 7 4 1 Vrolijkheid HISTORIC BUILDINGS 3 Nature Reserve 8 11 21 Bonnievale 62ZA 5 4 X 4 3 3 2 R317 1 1 16 BIRD WATCHING 4 4 3 8 4 2 7 1 5 HORSE RIDING DISTILLERIES 15 5 ZIP SLIDE 14 BREEDE RIVER 4 Riviersonderend mountains 3 5 CAVES 2 R60 DONKEY/BIRD SANCTUARY 3 HOT SPRINGS OTHER INFO 9 Swellendam 10 Riviersonderend N2 N2 MAP NOT TO SCALE CAMP SITES 19 Simonskloof Mountain Retreat | GPS: S33°36'57.2"E19°43'38.9" 4 Sheilam Nursery and Cactus and Succulent Garden TRACTOR TRIPS MTB ROUTES & BIKE HIRE 023 614 1895 023 626 4133 [email protected] [email protected] 1 African Game Lodge | GPS” S33°43'23.70' E20°21'07.84" www.sheilamnursery.com 1 Cape Dried Fruit Route 1 Bonfrutti | GPS: S33°55'20.40" E20°11'52.63" -

Contract RT57-2019 Contract Circular - Pricing for the Period 1 August 2020 to 30 November 2020 Date 14-Aug-20

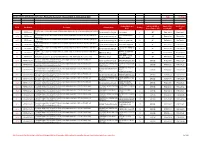

Contract RT57-2019 Contract Circular - Pricing for the period 1 August 2020 to 30 November 2020 Date 14-Aug-20 Combined Make and Subsidised(SUB) or Awarded Price New Price Incl. Ref # Item Number Description Company Name Ranking Model General Purpose (GP) IncludingVAT VAT Four/Five seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3/5 doors-piston displacement up to 1900cm3, Hybrid (pool vehicles 3352 RT57-00-01 Toyota South Africa (Pty) Ltd Prius 1.8 42G 1 GP R446,144.00 R446,144.00 only) Four/Five seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3/5 doors - piston displacement 1901cm³ to 3000cm³, Hybrid(Pool Lexus IS300H HYBRID 3354 RT57-00-02 Toyota South Africa (Pty) Ltd 1 GP R632,285.00 R632,285.00 vehicles only) 39M Four/Five seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3/5 doors - piston displacement 1901cm³ to 3000cm³, Hybrid(Pool 3357 RT57-00-02 Toyota South Africa (Pty) Ltd UX 250 SE Hybrid 68C 2 GP R637,424.00 R637,424.00 vehicles only) Four/Five seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3/5 doors - piston displacement 1901cm³ to 3000cm³, Hybrid(Pool 3355 RT57-00-02 Toyota South Africa (Pty) Ltd Lexus NX300 Hybrid 23T 3 GP R721,001.00 R721,001.00 vehicles only) Four/Five seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3/5 doors - piston displacement 1901cm³ to 3000cm³, Hybrid(Pool Lexus ES 300 HYBRID SE 3353 RT57-00-02 Toyota South Africa (Pty) Ltd 4 GP R765,485.00 R765,485.00 vehicles only) 21J Four/Five seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3/5 doors - piston displacement 1901cm³ to 3000cm³, Hybrid(Pool BMW 7 Series BMW 740e 363 RT57-00-02 BMW (South Africa) 5 GP R1,067,000.00 R1,067,000.00 vehicles only) Sedan (G11) BMW i BMW i3 (120Ah 364 RT57-00-07 Any Fully Electrical Vehicle (Sedan/Hatch/SUV/MPV) 4x2 or 4x4, NON-Hybrid (Pool vehicles only) BMW (South Africa) 1 GP R589,500.00 R589,500.00 BEV) Hatch (BMW i) Four seater sedan 4 door or hatch 3-5 doors ,piston displacement up to 1250 cm (Petrol/Diesel) 2630 RT57-01-12-01 Nissan South Africa (Pty) Ltd. -

Flower Route Map 2017

K o n k i e p en w R31 Lö Narubis Vredeshoop Gawachub R360 Grünau Karasburg Rosh Pinah R360 Ariamsvlei R32 e N14 ng Ora N10 Upington N10 IAi-IAis/Richtersveld Transfrontier Park Augrabies N14 e g Keimoes Kuboes n a Oranjemund r Flower Hotlines O H a ib R359 Holgat Kakamas Alexander Bay Nababeep N14 Nature Reserve R358 Groblershoop N8 N8 Or a For up-to-date information on where to see the Vioolsdrif nge H R27 VIEWING TIPS best owers, please call: Eksteenfontein a r t e b e e Namakwa +27 (0)72 760 6019 N7 i s Pella t Lekkersing t Brak u Weskus +27 (0)63 724 6203 o N10 Pofadder S R383 R383 Aggeneys Flower Hour i R382 Kenhardt To view the owers at their best, choose the hottest Steinkopf R363 Port Nolloth N14 Marydale time of the day, which is from 11h00 to 15h00. It’s the s in extended ower power hour. Respect the ower Tu McDougall’s Bay paradise: Walk with care and don’t trample plants R358 unnecessarily. Please don’t pick any buds, bulbs or N10 specimens, nor disturb any sensitive dune areas. Concordia R361 R355 Nababeep Okiep DISTANCE TABLE Prieska Goegap Nature Reserve Sun Run fels Molyneux Buf R355 Springbok R27 The owers always face the sun. Try and drive towards Nature Reserve Grootmis R355 the sun to enjoy nature’s dazzling display. When viewing Kleinzee Naries i R357 i owers on foot, stand with the sun behind your back. R361 Copperton Certain owers don’t open when it’s overcast.