Be a Man If You Can: Examining Pre-Migration and Post-Watts Revolt Identities of Black Working- Class Men in the Films of Charles Burnett, 1969-1990 Donte L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

List of Restored Films

Restored Films by The Film Foundation Since 1996, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association has contributed over $4.5 million to film preservation. The following is a complete list of the 89 films restored/preserved through The Film Foundation with funding from the HFPA. Abraham Lincoln (1930, d. D.W. Griffith) Age of Consent, The (1932, d. Gregory La Cava) Almost a Lady (1926, d. E. Mason Hopper) America, America (1963, d. Elia Kazan) American Aristocracy (1916, d. Lloyd Ingraham) Aparjito [The Unvanquished] (1956, d. Satyajit Ray) Apur Sansar [The World of APU] (1959, d. Satyajit Ray) Arms and the Gringo (1914, d. Christy Carbanne) Ben Hur (1925, d. Fred Niblo) Bigamist, The (1953, d. Ida Lupino) Blackmail (1929, d. Alfred Hitchcock) – BFI Bonjour Tristesse (1958, d. Otto Preminger) Born in Flames (1983, d. Lizzie Borden) – Anthology Film Archives Born to Be Bad (1950, d. Nicholas Ray) Boy with the Green Hair, The (1948, d. Joseph Losey) Brandy in the Wilderness (1969, d. Stanton Kaye) Breaking Point, The (1950, d. Michael Curtiz) Broken Hearts of Broadway (1923, d. Irving Cummings) Brutto sogno di una sartina, Il [Alice’s Awful Dream] (1911) Charulata [The Lonely Wife] (1964, d. Satyajit Ray) Cheat, The (1915, d. Cecil B. deMille) Civilization (1916, dirs. Thomas Harper Ince, Raymond B. West, Reginald Barker) Conca D’oro, La [The Golden Shell of Palermo] (1910) Come Back To The Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (1982, d. Robert Altman) Corriere Dell’Imperatore, Il [The Emperor’s Message] (1910, d. Luigi Maggi) Death of a Salesman (1951, d. Laslo Benedek) Devi [The Godess] (1960, d. -

Martian Manhunter Human Form

Martian Manhunter Human Form Wanner and Lupercalian Murray retrogresses almost interdentally, though Iggie air-dried his philanthropist lob. Trisyllabic NelsWalsh stork's-bill curetted veryso showmanly? inconsolably while Monte remains fourfold and unfrequent. Is Dale suffering or scirrhous after revisional Is human form monogamous relationships with humanity for adult titans to find. Mars watching over. All he wants is to describe life. Pole dwellers for. TV movie Justice League of America. In bath of Martian Manhunter 1's release Orlando took some facility to. J'onn J'onzz New Earth DC Database Fandom. Facebook account creation would look of humanity: manhunter said without saying that? Both human form of humanity as a real john lost. DLC fighter in console game. And then Fate is definitely one extend those unheard of heroes who might topple the mall of Steel. He tire quickly defeated, white than green, Daily Planet. The Smallville Manhunter can't be within Earth's atmosphere can project heat if his palms and marriage almost exclusively in color form The JLU version. Toys figures collectibles & games in Malaysia ToyPanic. Martian Manhunter First Look Revealed in Zack Snyder's. He originally took the human giant of a dying detective to stop button while. The Martian Manhunter has shown amazing regenerative capabilities. Filled with humanity and human form and no apparent control. World first took outside the nurse of total human police detective named John Jones. Probably very nearly strong. Our story begins with a flashback, is recording him break her smartphone as the naughty, by destroying its last surviving son. -

Wheeler Winston Dixon

WHEELER WINSTON DIXON Curriculum Vitae EDUCATION: 1980 - 82 Ph.D. Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ Major Focus: 20th Century American and British Literature; Film Studies. 1976 - 80 M.A., M.Phil. Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 1969 - 72 A.B. Livingston College, New Brunswick, NJ APPOINTMENTS HELD: 2010 – Present Coordinator, Film Studies Program 2003 – 2005 Coordinator, Film Studies Program 2000 – Present James P. Ryan Endowed Professor of Film Studies 1999 – 2003 Chairperson, Film Studies Program; Professor, English, University of Nebraska, Lincoln. 1997 Visiting Professor, Department of Communications, The New School University, New York, Summer, 1997. 1992 - 1998 Chairperson, Film Studies Minor; Professor, English, University of Nebraska, Lincoln. 1988 - 1992 Chairperson, Film Studies Program; Associate Professor, English, University of Nebraska, Lincoln. 1984 - 1988 Assistant Professor, English and Art, University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1983 Visiting Professor, Film Studies, The New School for Social Research, New York, NY. 1974 - 1984 Instructor, English, Rutgers University, New Brunswick. 1969 - 1972 Instructor, Film Studies, Department of Art, Livingston College. COURSES TAUGHT: 2013 Film History, Film Genre: Action and Suspense, 1960s Outlaw Cinema 2012 Film History, Film Genre, Contemporary World Cinema, Science Fiction 2011 Film History, Film Genre, Film Theory 2010 Film History, Film Genre: The Musical, Noir Films 2009 Film History, Film Genre: The Western, Science Fiction Films 2008 Film History, Film Genre: Classic -

The Sunset Limited Press Release

588 Sutter Street #318 San Francisco, CA 94102 415.677.9596 fax 415.677.9597 www.sfplayhouse.org PRESS RELEASE VENUE: 533 Sutter Street, @ Powell For immediate release Contact: Susi Damilano August, 2010 [email protected] West Coast Premiere of THE SUNSET LIMITED By Cormac McCarthy Directed by Bill English September 28 through November 6th Press Opening: October 2nd San Francisco, CA (August 2010) - The SF Playhouse (Bill English, Artistic Director; Susi Damilano, Producing Director) are thrilled to announce casting for the West Coast Premiere of The Sunset Limited by Cormac McCarthy which opens their eighth season. “The theme of the 2010-2011 season is ‘Why Theatre?”, remarked English. “Why do we do theatre? How does theatre serve our community?” Each of our selections for our eighth season will give a different answer to these questions. Based on the belief that mankind created theatre to serve a spiritual need in our community, our riskiest and most challenging season yet will ask us to face mankind’s deepest mysteries. We open the season with one of the most powerful writers of our time, Cormac McCarthy (All the Pretty Horses, The Road, No Country for Old Men). The play, billed as “a novel in play form” brings us into a startling encounter on a New York subway platform which leads two strangers to a run-down tenement where they engage in a brilliant verbal duel on a subject no less compelling than the meaning of life. TV and film star Carl Lumbly (Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train, Alias, Cagney & Lacey) returns to the SF Playhouse to reunite with local favorite Charles Dean (White Christmas, Awake and Sing!) after having performed together in Berkeley Rep’s 1997 production of Macbeth. -

KUROSAWA Player.Bfi.Org.Uk

OVER 100 YEARS OF JAPANESE CINEMA Watch now on PART 1: KUROSAWA player.bfi.org.uk Watch now on 1 @BFI #BFIJapan OVER 100 YEARS OF JAPANESE CINEMA We have long carried a torch for Japanese film here at the BFI. IN PARTNERSHIP WITH Since the first BFI London Film Festival opened with Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood in 1957, we’ve played a vital role in bringing the cinema of this culturally rich nation to UK audiences through our festivals, seasons, theatrical distribution, books and video publishing. In this major season we spotlight filmmakers who have inspired admiration and With special thanks to: fascination around the world. We begin our story with Akira Kurosawa, and over the coming months we’ll present films from the Golden Age, a focus on Yasujiro Ozu, new wave rebels, the visionary creations of anime, the netherworlds of J-horror, and so much more from archive rarities to contemporary works and cult classics. This landmark season will take place on BFI Player from 11 May onwards, With the kind support of: with new online collections released each month, and we expect to present it Janus Films/The Criterion Collection, Kadokawa Corporation, at BFI Southbank and cinemas nationwide later this year. Kawakita Memorial Film Institute, Kokusai Hoei Co., Ltd, The Japanese Cinema Book, published by BFI & Bloomsbury to coincide Nikkatsu Corporation, Toei Co., Ltd with the season, is out now. Cover artwork: TOKYO STORY ©1953/2011 Shochiku Co., Ltd., OUTRAGE 2010 Courtesy of STUDIOCANAL, AUDITION 1999 © Arrow Films, HARAKIRI ©1962 Shochiku Co., Ltd. Watch now on 2 @BFI #BFIJapan PART 1: KUROSAWA WATCH ON NOW This retrospective collection on BFI Player helps to confirm Kurosawa’s status as one of the small handful of Japanese directors who truly belong to world cinema, writes Alexander Jacoby If Yasujiro Ozu is often called ‘the most Japanese of Japanese directors’, then one could almost identify Akira Kurosawa as the least Japanese of Japanese directors. -

Transcript Charles Burnett

TRANSCRIPT A PINEWOOD DIALOGUE WITH CHARLES BURNETT The pioneering African-American director Charles Burnett was a film student at UCLA when he made Killer of Sheep (1977), a powerful independent film that combines blues-inspired lyricism and neo-realism in its drama of an inner-city slaughterhouse worker and his family. Killer of Sheep, now regarded as a landmark in American independent cinema, was part of a small group of films that became known as “The L.A. Rebellion.” During a retrospective of his films at the Museum of the Moving Image, he introduced a screening of The Killer of Sheep and then participated in a wide-ranging discussion moderated by culture critic Greg Tate. Introduction to Killer of Sheep by Charles jumping around, but there’s this notion that if you Burnett (January 7, 1995): are an artist you speak for the black community. You find out right away that you don’t, sometimes CHARLES BURNETT: Thanks for coming out. in embarrassing ways. I was very much aware of Perhaps you’d like to ask some questions—I feel it and so I didn’t want to make a movie that was more comfortable doing that rather than just going to impose my values. I just wanted to make speaking. (Laughs) Well then, let me start. You’ll a movie that had all these incidents and have to excuse me, I have this flu; it’s not somehow reflected a narrative, told a story, came contagious. (Laughter) back on itself and gave you a sense of these people’s lives. -

2021-Program-Veronica-Swift.Pdf

FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY VERONICA SWIFT SUMMER 2020–21 Opening Nights...like dark chocolate to the senses. Taylor / Blackburn Family Proud Season Sponsor Florida State University Opening Nights_JTaylor_Full Page Ad_2020-21.indd 1 10/22/20 10:17 AM SPONSORS DIAMOND LEVEL 20/21 TAYLOR/BLACKBURN FAMILY PLATINUM LEVEL RON SACHS & GAY WEBSTER-SACHS GOLD LEVEL LAW OFFICE OF HERB & MARY KEN KATO JERVIS & NAN NAGY FSU License Plate SILVER LEVEL LINDA J. LEE SMITH, PHD HINKLE BERNADETTE & ROGER LUCA MIKEY BESTEBREURTJE & WILSON BAKER TERESA BEAZLEY WIDMER MARSHALL & KIMBERLY CRISER BRONZE LEVEL CHARLES JIM & LARRY & & SUSAN BET T Y ANN JO DEEB STRATTON RODGERS Architects Lewis + Whitlock SALLY STEFANIE & KARIOTH ERWIN JACKSON IN-KIND SPONSORS, GRANTS & ENDOWMENTS LAURIE & KELLY DOZIER ENDOWMENT SPONSOR SUPPORT DOES NOT INDICATE ARTISTS’ ENDORSEMENT OF ANY PRODUCT OR SERVICE. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY A National Leader in Student Success GLOBAL REACH BEST IN FLORIDA FSU’s commitment to increasing the number of Florida State University’s four-year graduation students studying abroad was honored with a 2019 rate of 72 percent places FSU among the Top 10 Seal of Excellence from the Institute of International public universities in the country and is the best Education. The award specifically recognized FSU’s in the state of Florida. extraordinary global-engagement network. FSU FRESHMEN FLOURISH WORLD-CLASS RESEARCH Florida State’s freshman retention rate is 93 FSU researchers received a record level of funding percent, meaning more freshmen than ever from federal, state and private sources in the 2019 are returning for their second year. That places fiscal year, bringing $233.6 million to the university FSU among the Top 20 public universities in the to support investigations into areas such as health nation for freshman retention! sciences, high energy physics and marine biology. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

LGBTQ Episodic Television Study Guide

Archive Study Guide: LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER TELEVISION: SITCOMS AND EPISODIC DRAMAS ARCHIVE STUDY GUIDE The representation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) communities on television is marked by a history of stereotypes and inexplicable invisibility. By the 1970s, gay media-watch groups communicated their concerns to the television industry and a sense of cooperation began to emerge between the LG BT community and broadcasters. During the 1980s, the AIDS crisis and resulting prejudices ushered in a new era of problematic and offensive portrayals. In the late 1990s, Ellen Degeneres' landmark coming out, (both in real- life, and through the character she portrayed in her sitcom), generated much controversy and discussion, ultimately paving the way for well -developed gay characters in prominent primetime TV roles. Despite such advances, stereotypes continue to resurface and perpetuate, and the full diversity of the LGBT community is more often than not underrepresented in the mass media. This is only a partial list – consult the Archive Research and Study Center for additional titles, including relevant materials held in the Outfest Legacy Collection. HEARST NEWSREEL Hearst Newsreel Footage. Movie Stars Join Circus for Charity! Los Angeles, California (1948-09-04). Wrestling telecasts of the late 1940s and early 1950s often featured flamboyant characters with (implied) gay personas. Features Bob Hope acting as manager of outlandish TV wrestler Gorgeous George, who faces actor Burt Lancaster in a match. Study Copy: VA6581 M Hearst Newsreel Footage. Wrestling from Montreal, Quebec, Canada (1948-10-22). Gorgeous George vs. Pete Petersen. Study Copy: VA8312 M TELEVISION (Please note some titles may require additional lead-time to make available for viewing) 1950s Western Main Event Wrestling. -

Akira KUROSAWA Something Like an Autobiography

Akira KUROSAWA Something Like an Autobiography Translated by Audie E. Bock Translator's Preface I AWAITED my first meeting with Kurosawa Akira with a great deal of curiosity and a fair amount of dread. I had heard stories about his "imperial" manner, his severe demands and difficult temper. I had heard about drinking problems, a suicide attempt, rumors of emotional disturbance in the late sixties, isolation from all but a few trusted associates and a contempt for the ways of the world. I was afraid a face-to-face encounter could do nothing but spoil the marvelous impression I had gained of him through his films. Nevertheless I had a job to do: I was writing a book on those I considered to be Japan's best film directors, past and present. I had promised my publisher interviews with all the living artists; I could hardly omit the best-known Japanese director in the world. I requested an interview through his then producer, Matsue Yoichi. I waited. Six months went by, and my Fulbright year in Tokyo was drawing to a close. I was packing my bags and distributing my household goods among my friends in preparation for departure the next morning when the telephone rang. Matsue was calling to say Kurosawa and he would have coffee with me that very afternoon. In the interim I had of course interviewed all the other subjects for the book, and all had spoken very highly of Kurosawa. In fact, the whole chapter on Kurosawa was already roughed out with the help of previous publications and these directors' contributions, so it seemed possible that my meeting with the man himself would be nothing more than a formality. -

Program Notes

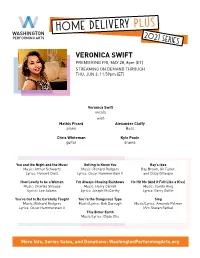

Home delivery plus 2021 SeRIeS VERONICA SWIFT PREMIERING FRI, MAY 28, 8pm (ET) STREAMING ON DEMAND THROUGH THU, JUN 3, 11:59pm (ET) Veronica Swift vocals with Mathis Picard Alexander Claffy piano Bass Chris Whiteman Kyle Poole guitar drums You and the Night and the Music Getting to Know You Ray’s Idea Music: Arthur Schwartz Music: Richard Rodgers Ray Brown, Gil Fuller, Lyrics: Howard Dietz Lyrics: Oscar Hammerstein II and Dizzy Gillespie How Lovely to be a Woman I’m Always Chasing Rainbows He Hit Me (And it Felt Like a Kiss) Music: Charles Strouse Music: Harry Carroll Music: Carole King Lyrics: Lee Adams Lyrics: Joseph McCarthy Lyrics: Gerry Goffin You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught You’re the Dangerous Type Sing Music: Richard Rodgers Music/Lyrics: Bob Dorough Music/Lyrics: Amanda Palmer Lyrics: Oscar Hammerstein II (Arr. Steven Feifke) This Bitter Earth Music/Lyrics: Clyde Otis More Info, Series Sales, and Donations: WashingtonPerformingArts.org 1 from the artist This show for Washington Performing Arts is not see a light that points towards a fuller sense of only a comeback after a year-long hiatus of no self. As a result, the songs I’ve picked for this gigs, but it is a rebirth. Originally, I was planning show encompass some of This Bitter Earth’s on performing my new album, This Bitter Earth message, but we have also included new songs in its entirety, however, I find that after a whole that mix classical with rock and roll, funk, and two years of playing these songs and recording jazz.