What Happened to the Institutional Critique? by James Meyer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Went to No Man's Land: Women Artists from the Rubell Family Collection

We Went to No Man’s Land: Women Artists from The Rubell Family Collection 12/22/15, 11:06 AM About Features AFC Editions Donate Sound of Art Search Art F City We Went to No Man’s Land: Women Artists from The Rubell Family Collection by Paddy Johnson and Michael Anthony Farley on December 21, 2015 We Went To... Like 6 Tweet Mai-Thu Perret with Ligia Dias, “Apocalypse Ballet (Pink Ring) and “Apocalypse Ballet (3 White Rings,” steel, wire, papier-mâché, emulsion paint, varnish, gouache, wig, flourescent tubes, viscose dress and leather belt, 2006. No Man’s Land: Women Artists from The Rubell Family Collection 95 NW 29 ST, Miami, FL 33127, U.S.A. through May 28, 2016 Participating artists: Michele Abeles, Nina Chanel Abney, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Kathryn Andrews, Janine Antoni, Tauba Auerbach, Alisa Baremboym, Katherine Bernhardt, Amy Bessone, Kerstin Bratsch, Cecily Brown, Iona Rozeal Brown, Miriam Cahn, Patty Chang, Natalie Czech, Mira Dancy, DAS INSTITUT, Karin Davie, Cara Despain, Charlotte Develter, Rineke Dijkstra, Thea Djordjadze, Nathalie Djurberg, Lucy Dodd, Moira Dryer, Marlene Dumas, Ida Ekblad, Loretta Fahrenholz, Naomi Fisher, Dara Friedman, Pia Fries, Katharina Fritsch, Isa Genzken, Sonia Gomes, Hannah Greely, Renée Green, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Jennifer Guidi, Rachel Harrison, Candida Höfer, Jenny Holzer, Cristina Iglesias, Hayv Kahraman, Deborah Kass, Natasja Kensmil, Anya Kielar, Karen Kilimnik, Jutta Koether, Klara Kristalova, Barbara Kruger, Yayoi Kusama, Sigalit Landau, Louise Lawler, Margaret Lee, Annette Lemieux, Sherrie Levine, Li Shurui, Sarah Lucas, Helen Marten, Marlene McCarty, Suzanne McClelland, Josephine Meckseper, Marilyn Minter, Dianna Molzan, Kristen Morgin, Wangechi Mutu, Maria Nepomuceno, Ruby Neri, Cady Noland, Katja Novitskoval Catherine Opie, Silke Otto-Knapp, Laura Owens, Celia Paul, Mai-Thu Perret, Solange Pessoa, Elizabeth Peyton, R.H. -

Mdms Fraser List of Works E.Docx

Andrea Fraser List of Works This list of works aims to be comprehensive, and works are listed chronologically. A single asterisk beside the title (*) indicates that an installation or project is represented in the exhibition only as documentation. Two asterisks (**) indicate that a work is not included in the exhibition. The context of a performance or work (for example commission, project, or exhibition) is listed after the medium. When no other performer is listed, the artist performed the work alone. When no other location is listed, videotapes document the original performance. Unless otherwise specified, videotapes are standard definition. If no other language is indicated, texts, performances, and videos are in English. Dates of performances are noted where possible. Dimensions are given as height x width x depth. Collection credits have been listed for series up to editions of three and public collections have been listed for editions of four to eight. Unless otherwise specified, exhibited works are on loan from the artist. Woman 1/ Madonna and Child 1506–1967 , 1984 Artist’s book Offset print, 16 pages 8 5/8 x 10 1/16 in. (22 x 25.5 cm) Edition: 500 Untitled (Pollock/Titian) #1 , 1984/2005 (**) Digital chromogenic color print 26 3/4 x 60 in. (67.9 x 152.4 cm) Edition: 5 + 1 AP Untitled (Pollock/Titian) #2, 1984/2005 (**) Digital chromogenic color print 27 x 60 in. (68.6 x 152.4 cm) Edition: 5 + 1 AP Untitled (Pollock/Titian) #3 , 1984/2005 (**) Digital chromogenic color print 40 x 60 in. (101.6 x 152.4 cm) Edition: 5 + 1 AP Untitled (Pollock/Titian) #4 , 1984/2005 (**) Digital chromogenic color print 40 x 61 in, (101.6 x 154.94 cm) Edition: 5 + 1 AP 1/5 Kemper Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO Untitled (de Kooning/Raphael) #1 , 1984/2005 (**) Digital chromogenic color print 40 x 30 in. -

Amelia Jones the Body As Archive/The Archive As Body: Live Art in Los Angeles 1970-75, a Case Study

Amelia Jones The Body as Archive/The Archive as Body: Live Art in Los Angeles 1970-75, A Case Study Countering the usual opposition between the "live" (believed to be authentic) and the "document" or "archive" (usually posed as secondary and thus as inferior), this paper will propose that the body can be understood itself as an archive and the archive as a "body." I use a specific research project attempting to historicize otherwise lost performance art practices from early 1970s Los Angeles to muddy this opposition, pointing to the continuum among the various levels through which performance art can be experienced: through first-hand viewing or participation, through later interviews with artists and participants, through documents, reenactments, and other detritus that find their way into archives. Focussing on the case study of live performance art in Los Angeles from 1970-1975, this essay will explore the limits of how we can excavate and write histories of specific periods or practices of live art. Drawing on my personal experience of the LA creative community starting a decade later (that is, as a researcher arriving late on the scene who can always only look back to a history of which she was not a part), archival and interview research, and existing written histories and documentary traces of LA performance in this period, I hope both to sketch the possibility of writing this partial history and the limits of what we can know about events that took place over time and in the past. Is it enough to ask an artist to explain past works and contexts? Is it enough to look at photographs, albums, sketches, flyers, and ticket stubs in local archives? Where does the "truth" of these past performance practices lie? Ultimately the paper will seek to begin to understand our persistent disavowal of the obvious impossibility of knowing either present or past performances (our insistence on discussing live art "as if" we can fix it in place and time, even though we can never know even what we see before us in this instant). -

Why Look at Dead Animals? Taxidermy in Contemporary Art by Vanessa Mae Bateman Submitted to OCAD University in Partial Fulfillme

Why Look at Dead Animals? Taxidermy in Contemporary Art by Vanessa Mae Bateman Submitted to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Contemporary Art, Design, and New Media Art Histories Vanessa Mae Bateman, May 2013 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. ! Copyright Notice This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. You are free to: Share – To copy, distribute and transmit the written work. You are not free to: Share any images used in this work under copyright unless noted as belonging to the public domain. Under the following conditions: Attribution – You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Noncommercial – You may not use those work for commercial purposes. Non-Derivative Works – You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. With the understanding that: Waiver — Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Public Domain — Where the work or any of its elements is in the public domain under applicable law, that status is in no way affected by the license. -

ALLAN Mccollum Brief Career Summary Allan Mccollum

ALLAN McCOLLUM Brief career summary Allan McCollum was born in Los Angeles, California in 1944 and now lives and works in New York City. He has spent over thirty years exploring how objects achieve public and personal meaning in a world constituted in mass production, focusing most recently on collaborations with small community historical society museums in different parts of the world. His first solo exhibition was in 1970 in Southern California, where he was represented throughout the early 70s in Los Angeles by the Nicholas Wilder Gallery, until it’s closing in the late 70s, and subsequently by the Claire S. Copley Gallery, also in Los Angeles. After appearing in group exhibitions at the Pasadena Art Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, his first New York showing was in an exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery, in 1972. He was included in the Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial Exhibition in 1975, and moved to New York later that same year. In 1978 He became known for his series Surrogate Paintings, which were shown in solo exhibitions in New York at Julian Pretto & Co., Artistspace, and 112 Workshop (subsequently known as White Columns), in 1979. In 1980, he was given his first solo exhibition in Europe, at the Yvon Lambert Gallery, in Paris, France, and in that same year began exhibiting his work at the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York, where he introduced his series Plaster Surrogates in a large solo exhibition in 1983. McCollum began showing his work with the Lisson Gallery in London, England, in 1985, where he has had a number of solo exhibitions since. -

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a Short Story by Jeffrey Eugenides

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides Author Marcoci, Roxana Date 2005 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art ISBN 0870700804 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/116 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art museumof modern art lIOJ^ArxxV^ 9 « Thomas Demand Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides The Museum of Modern Art, New York Published in conjunction with the exhibition Thomas Demand, organized by Roxana Marcoci, Assistant Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 4-May 30, 2005 The exhibition is supported by Ninah and Michael Lynne, and The International Council, The Contemporary Arts Council, and The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. This publication is made possible by Anna Marie and Robert F. Shapiro. Produced by the Department of Publications, The Museum of Modern Art, New York Edited by Joanne Greenspun Designed by Pascale Willi, xheight Production by Marc Sapir Printed and bound by Dr. Cantz'sche Druckerei, Ostfildern, Germany This book is typeset in Univers. The paper is 200 gsm Lumisilk. © 2005 The Museum of Modern Art, New York "Photographic Memory," © 2005 Jeffrey Eugenides Photographs by Thomas Demand, © 2005 Thomas Demand Copyright credits for certain illustrations are cited in the Photograph Credits, page 143. Library of Congress Control Number: 2004115561 ISBN: 0-87070-080-4 Published by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, New York 10019-5497 (www.moma.org) Distributed in the United States and Canada by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, New York Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Thames & Hudson Ltd., London Front and back covers: Window (Fenster). -

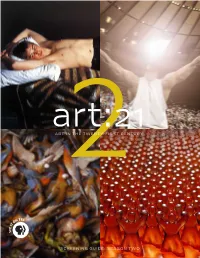

Art in the Twenty-First Century Screening Guide: Season

art:21 ART IN2 THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SCREENING GUIDE: SEASON TWO SEASON TWO GETTING STARTED ABOUT THIS SCREENING GUIDE ABOUT ART21, INC. This screening guide is designed to help you plan an event Art21, Inc. is a non-profit contemporary art organization serving using Season Two of Art in the Twenty-First Century. This guide students, teachers, and the general public. Art21’s mission is to includes a detailed episode synopsis, artist biographies, discussion increase knowledge of contemporary art, ignite discussion, and inspire questions, group activities, and links to additional resources online. creative thinking by using diverse media to present contemporary artists at work and in their own words. ABOUT ART21 SCREENING EVENTS Public screenings of the Art:21 series engage new audiences and Art21 introduces broad public audiences to a diverse range of deepen their appreciation and understanding of contemporary art contemporary visual artists working in the United States today and and ideas. Organizations and individuals are welcome to host their to the art they are producing now. By making contemporary art more own Art21 events year-round. Some sites plan their programs for accessible, Art21 affords people the opportunity to discover their broad public audiences, while others tailor their events for particular own innate abilities to understand contemporary art and to explore groups such as teachers, museum docents, youth groups, or scholars. possibilities for new viewpoints and self-expression. Art21 strongly encourages partners to incorporate interactive or participatory components into their screenings, such as question- The ongoing goals of Art21 are to enlarge the definitions and and-answer sessions, panel discussions, brown bag lunches, guest comprehension of contemporary art, to offer the public a speakers, or hands-on art-making activities. -

Michel Foucault and Modernist Art History

Manet, museum, modernism: Michel Foucault and modernist art history Alexander Kauffman Michel Foucault’s writing transformed the field of museum studies.1 As Kevin Hetherington reflected in a recent state-of-the-field volume, ‘Foucault can be seen as one of the two leading theoretical inspirations for critical museum studies since the 1980s [along with Pierre Bourdieu].’2 Foucault himself wrote little about the subject, but devoted substantial attention to the concurrent institutional formations of the prison, the clinic, and the asylum. Adaptations of those writings by Tony Bennett, Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, and other museum studies scholars triggered a reconfiguration of the field, sometimes known as ‘the new museology’ or ‘critical museum studies.’3 Instead of fading over time, Foucault’s presence has only grown as scholarship and public discourse around museums has increasingly focused on issues of power, authority, and subjectivity. Modernist art history enacted a parallel reception of Foucault, one that was transformative for that field as well, but is less well recognised today. Central to that reception was the art historian, critic, and curator Douglas Crimp, who died in 2019 at the age of seventy-four. Nearly a decade before Bennett and Hooper-Greenhill introduced Foucault to museum studies, Crimp wrote in an essay he boldly titled ‘On the Museum’s Ruins’: ‘Foucault has concentrated on modern institutions of confinement: the asylum, the clinic and the prison; for him, it is these institutions that produce the respective discourses of madness, illness, and criminality. There is another institution of confinement ripe for analysis in Foucault’s terms: the 1 This article originated in a paper for the 2019 College Art Association Annual Conference panel ‘Foucault and Art History’, convened by Catherine M. -

M a R K D I O N 1961 Born in New Bedford, MA Currently Lives In

M A R K D I O N 1961 Born in New Bedford, MA Currently lives in Copake, NY and works worldwide Education, Awards and Residencies 1981-82, 86 University of Hartford School of Art, Hartford, CT, BFA 1982-84 School of Visual Arts, New York 1984-85 Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Independent Study Program 2001 9th Annual Larry Aldrich Foundation Award 2003 University of Hartford School of Art, Hartford, CT, Doctor of Arts, PhD 2005 Joan Mitchell Foundation Award 2008 Lucelia Award, Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington D.C. 2012 Artist Residency, Everglades, FL 2019 The Melancholy Museum, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University, Stanford, CA Academic Fellowships 2015-16 Ruffin, Distinguished Scholar, Department of Studio Art, University of Virginia Charlottesville, VA 2014-15 The Christian A. Johnson Endeavor Foundation Visiting Artist in Residence at Colgate University Department of Art and Art History, Hamilton, NY 2014 Fellow in Public Humanities, Brown University, Providence 2011 Paula and Edwin Sidman Fellow in the Humanities and Arts, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI Solo Exhibitions (*denotes catalogue) 2020 The Perilous Texas Adventures of Mark Dion, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth* Mark Dion: Follies, Laumeier Sculpture Park, St. Louis, MO Mark Dion & David Brooks: The Great Bird Blind Debate, Planting Fields Foundation, Oyster Bay, NY Mark Dion & Dana Sherwood: The Pollinator Pavilion, Thomas Cole National Historic Site, Catskill, NY 2019 Wunderkammer 2, Esbjerg Museum of Art, Esbjerg, Denmark -

Authorship (Ext)Ended: Artist, Artwork, Public and the Curator: Ute Meta Bauer and Yvonne P

Ute Meta Bauer & Yvonne P. Doderer On Artistic and Curatorial Authorship Authorship (ext)ended: artist, artwork, public and the curator: Ute Meta Bauer and Yvonne P. Doderer interviewed by Annemarie Brand and Monika Molnár Annemarie Brand & Monika Molná r: We are therefore not less curators and leaders of art institu- currently at the Württembergischer Kunstverein tions are organizing panels and talks functioning as a Stuttgart, where the exhibition, Acts of Voicing. On the platform of exchange between producers, intermedi- Poetics and Politics of the Voice (October 12, 2012 – Jan- ators and recipients. uary 13, 2013) is showing. We would like to ask you both the role of the audience in an exhibition. In the One the one hand, and at a certain point, the context of this exhibition, the voice of the artist and public is also not alone. For example, while visiting the public are particularly important. Is it possible to an exhibition it is not always possible for direct com- think about this as a triangle; between the artists, munication to occur between artist, curator and the audience and the curator? public. Th erefore, curators and directors of art insti- tutions are organizing panels and talks, functioning Ute Meta Bauer: I have a problem with the as a platform of exchange between producers, inter- term audience, I would rather talk about a “public” - mediators and recipients. And at the end of the day the attempt of artists, curators to establish a public maybe it is even, like Roland Barthes said in the space. Because an audience to me is kind of passive. -

Louise Lawler: the Early Work, 1978-1985

RE-PRESENTING LOUISE LAWLER: THE EARLY WORK, 1978-1985 By MARIOLA V. ALVAREZ A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 Copyright 2005 by Mariola V. Alvarez To my parents. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge Alexander Alberro for his continuing guidance through the years, his encouragement during my writing process, and his intelligence, both tireless and nuanced, which serves as an exemplary model of scholarship. I would also like to thank both Eric Segal and Susan Hegeman for their perspicacious suggestions on my thesis and for their formative seminars. I am grateful to the rest of the faculty, especially Melissa Hyde, staff and graduate students at the School of Art and Art History whom I had the pleasure of working with and knowing. My friends deserve endless gratitude for always pushing me to be better than I am and for voluntarily accepting the position of editor. They influence me in every way. Finally, I thank my family for making all of this possible. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................. iv LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi ABSTRACT..................................................................................................................... viii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................1 -

Empty Fields Exhibition Brochure

EMPTY FIELDS Empty Fields April 6 - June 5, 2016 SALT Galata Curator Marianna Hovhannisyan SALT Research Sinem Ayşe Gülmez Saydam, Serkan Örs, Ahmet Metin Öztürk, Lorans Tanatar Baruh, Ersin Yüksel Editing Başak Çaka, November Paynter Exhibition Design Concept Fareed Armaly Design Consultant Ali Cindoruk Photography & Video Cemil Batur Gökçeer, Mustafa Hazneci Video Editing Alina Alexksanyan, Mustafa Hazneci Design Assistance Recep Daştan, Özgür Şahin Production Ufuk Çiçek, Gürsel Denizer, Çınar Okan Erzariç, Sani Karamustafa, Barış Kaya, Hüseyin Kaynak, Fuat Kazancı, Ergin Taşçı Translation Eastern Armenian: Zaruhi Grigoryan Greek: Haris Theodorelis-Rigas Ottoman Turkish-English: Michael D. Sheridan Turkish: Nazım Dikbaş Western Armenian: Sevan Değirmenciyan, Hrant Gadarigian, Hrag Papazian Empty Fields is the first exhibition to explore the archive of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), and the Protestant mission work in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. The project is made possible through the partnership of SALT, that has been cataloging and digitizing the archive, and the American Research Institute in Turkey (ARIT), the archive’s caretaker. In 2014 SALT sought the assistance of Marianna Hovhannisyan during the process of classifying this multilingual archive, and subsequently commissioned her to curate an exhibition that reflects on the contemporary agency of the available content. Hovhannisyan’s residency at SALT was supported by the Hrant Dink Foundation Turkey-Armenia Fellowship Scheme funded by the