Hegrenes Archive Submission: Chicago COVID

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Funding and Affordable Housing

Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Funding and Affordable Housing An analysis of current TIF resources and City of Chicago TIF-funded Housing 1995-2008 June, 2009 Sweet Home Chicago Coalition Action NOW Albany Park Neighborhood Council Bickerdike Redevelopment Corporation Chicago Coalition for the Homeless Jane Addams Senior Caucus Kenwood Oakland Community Organization Lakeview Action Coalition Logan Square Neighborhood Association Organization of the Northeast SEIU-Healthcare Illinois/Indiana SEIU Local 1 United Food and Commercial Workers Local 881 Report Prepared by Chicago Coalition for the Homeless on behalf of the Sweet Home Chicago Coalition Report Author: Julie Dworkin, Director of Policy, Chicago Coalition for the Homeless Researchers: Stephanie Procyk and Jim Picchetti Executive Summary A serious affordable housing crisis, which has plagued the City of Chicago for more than a decade, has deepened drastically during the last two years due to the rise in foreclosures and unemployment. Meanwhile, through its 158 active Tax Increment Financing (TIF) districts, the city has accumulated, and likely will continue to generate, a large surplus of funds that could be used to alleviate the affordable housing problem. TIF districts were created to promote revitalization of blighted or struggling neighborhoods, and the availability of affordable housing is instrumental to a neighborhood’s stability. Unfortunately, the city’s policy on the use of TIF funds for housing has not gone far enough to adequately address the fundamental need for affordable housing in developing neighborhoods. Expenditures on affordable housing have accounted for too small of a percentage of TIF funds. An even smaller percentage of TIF funds have supported housing affordable to people in the neighborhoods in which it is built and for those with the greatest housing needs. -

Abolish Tifs Now, the Civiclab Urges; Give the Money to Schools, Parks, Libraries

Abolish TIFs now, the CivicLab urges; give the money to schools, parks, libraries November 1, 2019 - Susan S. Stevens – Nov 1, 2019 http://eedition.gazettechicago.com/app.php?RelId=6.9.3.0.1 Tom Tresser, being interviewed by Hard Lens Media, along with Jonathan Peck, announced the CivicLab’s effort to completely eliminate TIFs in Chicago. The Tax Increment Financing (TIF) program in Chicago harms the blighted communities it was designed to help and benefits richer neighborhoods, officials of the CivicLab said in announcing a campaign to abolish TIFs. CivicLab declared that TIFs are, “harmful, unfair, racist, and beyond repair” in a statement and at the organization’s 78th public forum and Future of Chicago lecture, held at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) on Oct. 16. It further declared that “City services have been cut all along” because of property tax money diverted to special accounts designed to improve communities. After researching the impact of Chicago’s TIF program for six years, the CivicLab launched the TIF Elimination Project and called for distributing the $1.5 billion in TIF funds to schools, parks, libraries, and essential City services. It created an online petition directed at Mayor Lori Lightfoot and the Chicago City Council that can be found at https://tinyurl.com/End-TIFs-Now and https://tinyurl.com/End-TIFs-Action-Center. “TIFs are racist,” preying on African Americans and Hispanics, said the CivicLab’s co-founder and vice president Tom Tresser “TIFs must be abolished. They cannot be fixed. They are a big deal all over the City of Chicago. -

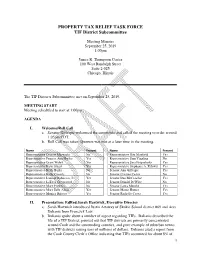

Sep 25 PTAX TIF DRAFT Minutes

PROPERTY TAX RELIEF TASK FORCE TIF District Subcommittee Meeting Minutes September 25, 2019 1:00pm James R. Thompson Center 100 West Randolph Street Suite 2-025 Chicago, Illinois The TIF Districts Subcommittee met on September 25, 2019. MEETING START Meeting scheduled to start at 1:00pm AGENDA I. Welcome/Roll Call a. Senator Gillespie welcomed the committee and called the meeting to order around 1:05pm CDT. b. Roll Call was taken. Quorum was met at a later time in the meeting. Name Present Name Present Representative Deanne Mazzochi No Representative Rita Mayfield Yes Representative Frances Ann Hurley Yes Representative Sam Yingling No Representative Grant Wehrli Yes Representative Sara Feigneholtz Yes Representative Katie Stuart Yes Representative Stephanie A. Kifowit Yes Representative Kelly Burke No Senator Ann Gillespie Yes Representative Kelly Cassidy No Senator Cristina Castro No Representative Lamont Robinson, Jr. Yes Senator Dan McConchie Yes Representative LaToya Greenwood No Senator Donald DeWitte No Representative Mary Flowers No Senator Laura Murphy Yes Representative Mary Edly -Allen Yes Senator Mattie Hunter Yes Representative Monica Bristow Yes Senator Rachelle Crowe Yes II. Presentation: EdRed Sarah Hartwick, Executive Director a. Sarah Hartwick introduced Justin Attaway of Skokie School district #69 and Ares Dalianis from Franczek Law. b. Dalianis spoke about a number of aspect regarding TIFs. Dalianis described the life of a TIF District, pointed out that TIF districts are primarily concentrated around Cook and the surrounding counties, and gave example of suburban towns with TIF districts raising tens of millions of dollars. Dalianis cited a report from the Cook County Clerk’s Office indicating that TIFs accounted for about 8% of 1 property taxes in Cook County, up from prior years. -

Tax Increment Financing: Faqs

Tax Increment Financing: FAQs 1) What is Tax Increment Financing (TIF) and how widely is it used? a) TIF is an economic development tool to encourage private investment b) 49 States and D.C. have a TIF law. CA first used TIF in 1952 c) Illinois adopted TIF in 1977 d) As of 2020: 500 Illinois municipalities in 96 counties use TIF e) There are nearly 1,500 active TIFs in Illinois f) There are over 350 active TIFs in Cook County 2) Why use TIF? a) TIF is locally controlled by the local city, not dependent on county, state or federal approval b) TIF does not raise taxes on existing property to pay for redevelopment c) TIF may be used to stimulate economic development and redevelopment d) TIF may be used to pay various redevelopment costs, including public improvements and infrastructure e) TIF enhances the tax base of local governments to reduce tax burden on other properties f) TIF retains and creates new jobs 3) Who pays for TIF, and Is TIF a new tax? a) TIF is not a new tax. TIF is not a tax break or abatement. TIF does not raise taxes. b) All properties within a TIF continue to pay property taxes as normal c) Schools, parks, libraries, counties, etc. continue to receive “Base Taxes” levied on property value at the time a TIF is adopted d) Property Taxes resulting from added value of new development is referred to as Incremental Property Tax (IPT) revenue (or “TIF Revenue”) and is used to pay redevelopment costs 4) How does TIF operate? a) A city adopts a (1) Redevelopment Plan, (2) designates a Redevelopment Project Area, and (3) adopts the use of TIF b) A TIF lasts 23 years (or 35 with special state legislation), and may be dissolved sooner c) Local governments continue to receive Base Taxes for the duration of the TIF d) A city temporarily captures IPT revenue during the life of the TIF to pay redevelopment costs, and the revenue is used to pay redevelopment costs e) To pay redevelopment project costs a city may combine TIF funds with other funding sources including and not limited to Local Sales Tax and Business District Sales Tax. -

December 19, 2019 Amendment to Planned Development No. 1434 101-213 West Roosevelt Road

Chicago Plan Commission Department of Planning and Development December 19, 2019 Amendment to Planned Development No. 1434 101-213 West Roosevelt Road/ 1200-1558 South Clark Street, Chicago, IL SITE LOCATION Status: . City Council approved PD No.1434 (last amended Near South 12/12/2018), which Community established the current Area development rights for the 62 acre site. Planned . Development Applicant is seeking new amendment to allow a CTA Near South No. 1434 Community Transit Station to be built Area within the boundary of PD No. 1434. Aside from the proposed CTA Station use, no additional development rights would be granted by this proposed amendment. 2 The 78 – Waterway Residential-Business Planned Development #1434 Current Condition Future Vision 3 Proposed New Station . 1.3 mile gap between the CTA Redline Stations at Roosevelt Rd. & Cermak Rd. New station proposed at the intersection of W. 15th St. & S. Clark St. Originally, the CTA station was proposed to be located on CTA- owned land east of S. Clark St., outside of PD #1434. Local residents requested that the proposed station be moved west of S. Clark St., inside the boundary of PD# 1434. Previous Location – East of Clark St., Outside PD #1434 New Location – West of Clark St., Inside PD #1434 PD SUB-AREA MAP PROPOSED TEXT AMENDMENT PLANNED . Add “Major Utilities and Services DEVELOPMENT NO. 1434 (for a CTA Transit Station and Accessory Uses only)” to allow new CTA station to be built within the boundaries of PD # 1434. Add “A School Impact Study will be required with any future site Cotton Tail plan submittal involving Park Proposed residential development” Previous Location Proposed (Inside (Previously, a study would only have been done Location PD#1434) (Outside of through mutual agreement of the City and the PD#1434) Sub-Area Applicant.) 2 = CTA Station 6 Concept Rendering New Office Building with CTA Station W. -

Ann Thompson

Ann Thompson Ann Thompson, Senior Vice President, Architecture and Design – Related Midwest Ann Thompson, AIA, is Senior Vice President of Architecture and Design of Related Midwest, leading the design and planning of projects across the company’s portfolio of mixed-use, mixed-income, affordable and luxury developments, as well as all engineering, zoning and entitlement efforts. Ms. Thompson has spent 24 years with the company, overseeing the design of more than 2,700 residences, with another 1500 in the pipeline. Ms. Thompson directs the work of architecture, urban planning, and engineering firms to oversee the design vision for Related Midwest’s transformative projects in Chicago, such as the reimagination of the historic Lathrop community along the Chicago River on the city’s north side; One Bennett Park, the first Robert A.M. Stern- designed residential tower in Chicago; and The 78: a 62-acre downtown development at the southwest corner of Clark Street and Roosevelt Road. One of the largest real estate projects in Chicago history. The 78 will be a vibrant mixed-use neighborhood that serves as a model for socially responsible development, with 12 acres of publicly accessible green and open space, including a halfmile of pedestrian-friendly riverfront, and a commitment to workforce development that prioritizes lead roles in construction and permanent operations for local women- and minority-owned businesses. Ms. Thompson is a licensed architect in Illinois and sits on the boards for the Chicago Architecture Center and the Lycee Francais de Chicago. In addition, Ms. Thompson is a member of the Women’s Board of the Alliance Francais, the International Women’s Forum and the American Institute of Architects. -

Protecting Low Income Residents During Tax Increment Financing Redevelopment

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 36 Restorative Justice 2011 Protecting Low Income Residents During Tax Increment Financing Redevelopment Kristen Erickson Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kristen Erickson, Protecting Low Income Residents During Tax Increment Financing Redevelopment, 36 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 203 (2011), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol36/iss1/9 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protecting Low Income Residents During Tax Increment Financing Redevelopment Kristen Erickson INTRODUCTION In 1997, tax increment financing (TIF) was used to fund the addition of a high-end department store to a suburban mall located in a wealthy outer suburb of St. Louis, Missouri.1 Over a decade later, another TIF project is in the works in the blighted, burned out, and mostly abandoned north St. Louis city, seeking to bring development, as well as vibrancy and affluence, back to that neighborhood.2 These two projects are examples of the uses to which tax increment financing, generally designed for redevelopment of blighted inner cities,3 has been put. Both projects also showcase potential problems associated with their use. On the one hand, TIF has been used rather effectively in wealthier communities to fund large commercial retail development. -

'Hoopademix' Summer Basketball Camp Brings Chicago Kids Together

CHICAGO Jul 23, 2020 9:15AM CDT The developer was willing to convert Fleet Fields, formerly ‘Hoopademix’ Summer publicly available soccer fields, into what Monson needed for Basketball Camp Brings Hoopademix. Chicago Kids Together — At The North Lawndale A Distance resident and Chicago Public Schools By Hannah Alani educator created the program to bring kids from different backgrounds together through basketball — a mission that became even more critical during nationwide protests after police killed George Floyd in Minneapolis. Kandace Miggins and Dietrich Ziegler/Provided “I wanted to use the game of basketball to BUCKTOWN — Coronavirus canceled many children’s destroy the institution activities this summer, but one basketball camp is still underway, of racism,” Monson bringing kids from across the city to Bucktown. said. “To weed out insecurities these groups have. … Being able to put everybody Hoopademix, a youth basketball instruction and mentorship under the same umbrella at an early age … it’s a really different, program, is meeting for outdoor practices at Fleet Fields, a beautiful thing when you get a kid from the Gold Coast mixed set of soccer fields on the Bucktown side of the Lincoln Yards with a kid from Englewood.” megadevelopment. Developer Sterling Bay lent the fields, 1397 W. Wabansia Ave., to the camp for free. Socially distanced summer camp looks a lot different than a typical Hoopademix season. Marpray “Coach Pray” Monson founded Hoopademix in 2013. Before the coronavirus pandemic, Hoopademix had 200 players All campers are playing in groups of no more than six children. spread between 22 teams. They played indoors in a variety of Basketballs are sanitized between use and players wash their gyms. -

Summary of LTA and CP Applications Received

Summary of Local Technical Assistance and Community Planning Applications October 29, 2019 CMAP established the Local Technical Assistance program to direct resources to communities to pursue planning work that helps to implement GO TO 2040 and now ON TO 2050. In conjunction with the RTA’s Community Planning program, the agencies opened a call for projects on September 17, 2019. This year, applicants were able to apply to both programs through a single online application. This agency coordination allows both agencies to offer planning and plan implementation assistance to an expanded base of eligible applicants, and align all efforts with CMAP’s ON TO 2050 priorities, and/or Invest in Transit, the 2018-2023 Regional Transit Strategic Plan, and provide technical assistance in a coordinated manner to the entire region. Applications were due on October 18, 2019. Application Breakdown by County and Project Type 81 applications were received from 70 different applicants. Below is a breakdown of applications by County. Some project application study areas fall in multiple counties, therefore the list below counts some applications multiple times. Please see the map below for approximate locations of all applications received. County Number of 2019 Suburban Cook 35Applications Chicago 16 DuPage 7 Kane 7 Kendall 1 Lake 6 McHenry 3 Will 7 Regional 3 ' ' ' e ' ' e e ' McHenry ' ' Lake 2019 ' 30 ' !' ' ' Local Technical 27 e ' ! ' ' ' ' !32 57 ' Assistance !' ' ' Program Applications ' ' ' Regional Distribution 74 ' ' e ! ' ' ' ' 55 ' ! !38' ' ' -

Working Paper No. 2013-01 Does Chicago's Tax Increment Financing (TIF)

Working Paper No. 2013-01 Does Chicago’s Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Program Pass the ‘But-For’ Test? Job Creation and Economic Development Impacts Using Time Series Data T. William Lester, Assistant Professor Center for Urban and Regional Studies The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Campus Box 3410, Hickerson House Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3410 Telephone: 919-962-3074 FAX 919-962-2518 curs.unc.edu February 2013 Does Chicago’s Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Program Pass the ‘But-For’ Test? Job Creation and Economic Development Impacts Using Time Series Data T. William Lester Assistant Professor University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill 320 New East Building (MC #3140) Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3140 [email protected] February, 12th 2013 ABSTRACT Chicago is one of the most extensive users of Tax Increment Financing (TIF) in the U.S. to promote economic development, with 160 districts designated since 1984. This paper conducts a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of TIF in Chicago in creating economic opportunities and catalyzing real estate investments at the neighborhood scale. This paper uses a unique panel dataset at the block group level to analyze the impact of TIF designation and funding on employment change, business creation, and building permit activity. After controlling for potential selection bias in TIF assignment, this paper shows that TIF ultimately fails the ‘but-for’ test and shows no evidence of increasing tangible economic development benefits for local residents. Implications for policy are considered. Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Rachel Weber and Daniel Hartley for sharing critical data sources and helpful comments. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 19, 2019 CONTACT

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 19, 2019 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] MAYOR LIGHTFOOT CREATES COMMUNITY ADVISORY COUNCIL TO ENSURE NEIGHBORHOOD INPUT ON THE 78 DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Community Engagement Effort Delivers on Mayor Lightfoot's Commitment to Inclusive Neighborhood Development CHICAGO—Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot, with support from Alderman Byron Sigcho- Lopez (25th) and developer Related Midwest, today announced the formation of a Community Advisory Council (CAC) that will serve as a conduit for community input as the $7 billion “The 78” development project on the Near South Side moves forward. Working with the developer and the local aldermen, the City is soliciting applications from community members to serve on the CAC. An application for CAC volunteers is available at www.chicago.gov/78. "When I first entered office, I made a commitment to ensure that all major planning efforts, including large-scale development projects like The 78, will be met with robust and inclusive community engagement processes,” said Mayor Lightfoot. “The 78 Community Advisory Council will provide a transparent process for residents and other stakeholders to provide guidance, identify improvements, and maximize economic opportunities for the community and the city at large as design and construction gets underway.” The 17-member CAC will consist of neighborhood representatives, community leaders, design professionals, and subject-matter experts appointed by Mayor Lightfoot and Ald. Sigcho-Lopez in consultation with neighboring aldermen and local stakeholders. The group will meet quarterly starting in early 2020, making recommendations ranging from public infrastructure design to traffic control and open space, among other issues. -

Tax Increment Finance: a Success-Driven Tool for Catalyzing Economic Development and Social Transformation Toby Rittner Council of Development Finance Agencies (CDFA)

Community Development INVESTMENT REVIEW 131 Tax Increment Finance: A Success-Driven Tool for Catalyzing Economic Development and Social Transformation Toby Rittner Council of Development Finance Agencies (CDFA) n the wake of an economic downturn, many cities are left with sites, projects, districts, or entire urban cores requiring redevelopment. The need for social improvements such as community centers, school rehabs, and parks has also become a critical development challenge. However, the ongoing risks of the development market require communities Ito be even more diligent and aware when entering into the use of public financing mecha- nisms such as Pay for Success (PFS) financing. One such mechanism, tax increment finance (TIF), has the potential to forge a new path for communities to fund development projects on the basis of their success. What Is Tax Increment Finance? TIF is a targeted development finance tool that captures the future value of an improved property to pay for the current costs of those improvements. This mechanism can be used to finance costs typically pertaining to public infrastructure, land acquisition, demolition, utilities, planning, and more. TIF funds have also been used to help support community amenities such as parks, recreational facilities, schools, and network infrastructure. TIF can focus attention on a problematic area and catalyze development that addresses both the economic needs of a community and the quality-of-life advancements that improve cities. Dozens of TIF projects have been introduced throughout the country, including the University North Park project, which adds both mixed-use development and a beautiful park to Norman, Oklahoma, and the “Green Corridor” project, which aims to create a business park as well as to clean and connect waterfront public spaces in Baltimore, Maryland.