The Pinking of Drinking: Understanding Women's Alcohol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 2021 News & Events

YOUR RED TAIL CASH CARDS FATHER’S DAY EXPIRE JUNE 30TH!!MEN’S The INVITATIONAL cards Mother’sMUSICAT REDDay AT TAIL JulyMayJune 2021 20212021 may be used for foodRed purchases Tail’s premier golf event begins THE PATIO Treat Dad this News & Events above your monthlyThursday, food minimum July 22nd through DinnerEnjoy To the musical Go Staying in this Mother’sFather’s Day? Day requirement, along Saturday,with alcohol, July Golf 24th. The Member/ stylings of local talent all Sunday,Celebrate June with20th a, withtruly spectaculara truly ShopGuest merchandiseInvitational is and three guest exceptional fees. Red days of challenging summer long on select Office and Dinner Reservations 440.937.6018 • Pro Shop 440.937.6286 amazingMother’s day! DayRed Dinner!Tail Golf Enjoy Staff our will Tailgolf, Cashoutstanding Cards CANNOTfood, and FUN! BE USED Day one starts with Saturdays at the Patio MOTHER’S DAY have Herbgames, Roasted prizes Prime and specials Rib Dinner on the with towardslunch at theany Patio outstanding Café followed balance by oweda practice round of golf Café. Gather together featuring SkillsBRUNCH Challenges throughout the course.course Theaccompaniments allday day! Call the including pro-shop Au to Jus FOURTH OF-SWIMMING JULY POOL NEWS - the Club, Swim or Tennis Lessons, and book your tee time!and spendChildren a fun of eveningall ages concludesSaturday, with May a delicious9th from steak 10:00am dinner for the attendees& creamy horseradish sauce, Grilled MEMORIAL DAY WEEKEND – THANK YOU TO ALL WHO HAVE SERVED! Cart and/or Walking Fees. Your Red are welcome! Kidsenjoying under live, 12 are acoustic free! The Fourth of back at the Club. -

How Women Perceive Portrayed Ideas of Masculinity in Alcohol Advertising

Beer is for boys; wine is for women: How women perceive portrayed ideas of masculinity in alcohol advertising _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Journalism _______________________________________ by RENEE SCHILB Dr. Cristina Mislán, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2017 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled BEER IS FOR BOYS; WINE IS FOR WOMEN: HOW WOMEN PERCEIVED PORTRAYED IDEAS OF MASCULINITY IN ALCOHOL ADVERTISING presented by Renee Schilb, a candidate for the degree of master of journalism and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ___________________________________________ Professor Cristina Mislán ___________________________________________ Professor Jon Stemmle ___________________________________________ Professor Sungkyoung Lee ___________________________________________ Professor Don Meyer ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Christina Mislan for her guidance and support throughout this long process. You have provided me with incredible amounts of time and attention, for which I am so grateful. Your refined attention to detail has elevated the level of my work and made this study truly successful. To my committee members, Professor Don Meyer and Dr. Sungyoung Lee, I want to extend a colossal thank you for graciously lending me your time and wide expanse of knowledge to help me perfect the details of my study. I also would like to extend my appreciation to the wonderful women who participated in my research and shared their time and stories with me. Your participation and commentary made this study what it is and I could not have done this without all of you. -

Talking to Strangers: the Use of a Cameraman in the Office and What

Running Head: TALKING TO STRANGERS 1 Talking to Strangers The Use of a Cameraman in The Office and What It Reveals about Communication Sarah Stockslager A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Fall 2010 TALKING TO STRANGERS 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Lynnda S. Beavers, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Robert Lyster, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ James A. Borland, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date TALKING TO STRANGERS 3 Abstract In the television mock-documentary The Office, co-workers Jim and Pam tell the cameraman they are dating before they tell their fellow co-workers in the office. The cameraman sees them getting engaged before anyone in the office has a clue. Even the news of their pregnancy is witnessed first by the camera crew. Jim and Pam’s boss, Michael, and other employees, such as Dwight, Angela and others, also share this trend of self-disclosure to the cameraman. They reveal secrets and embarrassing stories to the cameraman, showing a private side of themselves that most of their co-workers never see. First the term “mock-documentary” is explained before specifically discussing the The Office. Next the terms and theories from scholarly sources that relate the topic of self-disclosure to strangers are reviewed. Consequential strangers, weak ties, the stranger- on-a-train phenomenon, and para-social interaction are studied in relation to the development of a new listening stranger theory. -

The Bartender's Handbook Of

THE BARTENDER’S HANDBOOK OF FANCY COCKTAILS & CONCOCTIONS MAL TWISKIE Ex Libris William John Bardsley 2 3 A BARTENDER’S HANDBOOK OF FANCY COCKTAILS & CONCOCTIONS MAL TWISKIE Scarfes Bar Cocktail Book Vol. 1 Published by Rivington Bye Ltd. on behalf of Rosewood London high holborn, london mdccclxiv london mmxviii fruity & spiced Cocktail recipes? I’ll give you a cocktail recipe. Take one 50/50 boring old book, fill with a bunch of posh tweeds and 2009 TARTAN SPARTAN celebrity attention-seekers and drop in a few pretentious 2014 ingredients no one’s ever heard of. Muddle with the superior sketches of a totally genius (and handsome) LITTLE CABBAGE 2017 cartoonist et voilà – perfection on ice, shaken not stirred. SILVER SPOON 2013 ON YER BIKE 2008 Cocktails have got layers, the bartenders here tell me. TOOT TOOT 2016 They’re full of secrets and surprises. So I’ve got a little OFF THE MARKET dry & bitter 2018 surprise for you here, too. I’ve added a few layers of my NATURALIST 2006 own to this dust-gatherer of a book. A little Scarfination has improved many a dull tome. HIGH WASTED fresh & floral fresh 2004 Oh, I know I’ve got a bar named after me, blah blah. PATRONUS NECK IT 2010 2015 But a whole book of cocktails inspired by all the main BOOYAKASHA! 2003 people and events in recent history since the Millenium, OFFICE GOSSIP 2001 and no one thought to celebrate little old me? No Gerald Martini? No fruity Scarfarita? No Scarfe Island Iced DROP SHOT Tea or even a Bloody Scarfey? Well I’ll show you, the 2012 BACK TO BLACK pen is mightier than the shaker… 2011 ZINGY STARDUST 2002 DOC NO. -

Satire Dual-Edged, but Spare

AMERICA’S LARGEST CIRCULATION GAY AND LESBIAN NEWSPAPER! NEWSTM YOUR FREE WEEKLY NEWSPAPER JULY 9-22, 2009 VOL. EIGHT, ISSUE 14 SERVINGGay GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANSGENDERED City NEW YORK • WWW.GAYCITYNEWS.COM ■ CRIME ■ HUMAN RIGHTS Surge In East Sodomy Victory Side Hate In India Crimes BY ARTHUR S. LEONARD BY PAUL SCHINDLER regional high court in India has overturned that nation’s sodomy our days after being attacked, A law, a vestige of British colonial beaten on the head with a gun, and rule. The High Court in the National F called “faggot,” Joseph Holladay’s Capital Territory in New Delhi ruled that forehead remained scarred with a large, Section 377 of the India Penal Code vio- blood-red gash, and his voice quavered as lates constitutional guarantees of pri- he recounted the experience. vacy, liberty, and equality in its crimi- “Suddenly, out of nowhere, I was nalization of private, consensual, adult attacked by some men, they were call- sexual conduct. ing me faggot,” he said at a July 1 press The ruling came on a test case brought conference. “They beat me hard, and by a non-profit advocacy group, the NAZ unconscious, leaving me laying in a pool of Foundation. The Times of India reported blood.” that the nation’s Supreme Court has The next thing Holladay, 36, remem- made clear that a ruling of this sort by bers is waking up in New York Presbyte- the High Court of any province or state rian Hospital, where he was treated in the on a constitutional question not previ- emergency room and given multiple stitch- ously addressed by the judiciary has es in his head. -

90-012690.Compressed.Pdf

THIS SUNDAY Houston's Largest Super Bowl Party See the game on our Super Screen 3 pm Tailgate Party Hot Dogs and Munchies Fruity Field Goals & a Touchdown New Monday Mania 7 pm -1 am $3 Pitchers of Frozen Margaritas with Muscles In Action 710 PACIFIC if,,~'······L··""················~@···l •.~.\\ ~:b c...~ :b>~ .~'" Q~ ::o~ ::0 rilo .Q:r~~ 21 NEWS Gay Witch Hunt at Caswell Air Force Base 31 COMMENT Letters to the Editor 37 AT RANDOM Winter Vacation Break byW.W. Wells III 41 BOOK Finale: Mystery & Suspense Reviewed by Noel Gillespie 44 BACKSTAGE Don Maines and Reindeer Games by Marc Alexander 47 CLASSIC TwT 14Years Ago ThisWeek In Texas by Bob Dineen 50 HOT TEA Mark Collins Wins Mr. Houston Contest 57 SPORTS Valentine's Day Bowling Fund-Raiser in Houston byBobbyMlller 59 STARSCOPE Your February Lovescope by Milton von Stern 62 COVER FEATURE Gervais Wright Photos by Julee Hollingsworth 65 CALENDAR Special One-Time Only and Nonprofit Community Events 67 CLASSIFIED Want Ads and Notices 76 GUIDE TexasBusiness/ClubDirectory TWT (This Week in Texas) is published by Texas Weekly Times Newspaper Co .. at 3900 lemmon AV9. in Dallas. Texes 75219and an Westheimer in Houston, Texes 77006. Opinions expressed by columnists are not necessarily those of TWT or of its staff. Publication of the name or photograph of cny person or organization in articles or advertising in TWT is not to be construed as any indication of the sexual orientation of said person or organization. Subscription rates: $69 per year, $55 per half year. Back issues available at 52 each. -

Cocktails Crafted with 1792 Bourbon

COCKTAILS CRAFTED WITH 1792 BOURBON TABLE OF CONTENTS 1792 BOURBON 5 BARTON 1792 DISTILLERY 7 GEORGIA SMASH 8 MANHATTAN BEACH 10 OLD FASHIONED 12 THE POCKET SQUARE 14 THE DU MONDE 18 THE PB&A 20 WHISKEY SOUR 22 WINTERFALL 24 FASHION TIPS BY TOM JAMES 27 1792 BOURBON Sophisticated and complex. A distinctly different bourbon created with precise craftsmanship. Made from our signature “high rye” recipe and the marriage of select barrels carefully chosen by our Master Distiller, 1792 Bourbon has an expressive and elegant flavor profile. Unmistakable spice mingles with sweet caramel and vanilla to create a bourbon that is incomparably brash and bold, yet smooth and balanced. Elevating whiskey to exceptional new heights, 1792 Bourbon is celebrated by connoisseurs worldwide. GOLD GOLD LOSANGELES MEDALDENVER INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONAL SPIRITSCOMPETITION SPIRITSCOMPETITION Small Batch Small Batch GOLD WORLD INTERNATIONAL WHISKIESAWARDS SPIRITSCHALLENGE WORLD’SBEST BOURBON Small Batch Full Proof 1792 Bourbon 5 WHERE IT ALL BEGINS BARTON 1792 DISTILLERY Barton 1792 Distillery was established in 1879 and continues today as the oldest fully- operating distillery in Bardstown, Kentucky. Situated in heart of bourbon country on 196 acres, Barton 1792 Distillery boasts 29 barrel- aging warehouses, 22 other buildings including an impressive still house, and the legendary Tom Moore Spring. Barton 1792 Distillery 7 GEORGIA SMASH CRAFTED BY JEFFREY MORGENTHALER, AUTHOR OF "DRINKING DISTILLED" AND CO-AUTHOR OF "THE BAR BOOK: ELEMENTS OF COCKTAIL TECHNIQUE." “The peach and mint aromas of this cocktail will have you thinking hot summer days and thirst-quenching refreshment. The 1792 Bourbon brings in the smash to give the refreshment a quick shove to where you need to be.” INGREDIENTS INSTRUCTIONS – 2 oz. -

Report on Preliminary Examination Activities 2019

Report on Preliminary Examination Activities (2019) 5 December 2019 Report on Preliminary Examination Activities 2019 5 December 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I. SITUATIONS UNDER PHASE 1 ............................................................................. 8 II. SITUATIONS UNDER PHASE 2 (SUBJECT-MATTER JURISDICTION) ... 18 Venezuela ........................................................................................................... 18 III. SITUATIONS UNDER PHASE 3 (ADMISSIBILITY) ....................................... 24 Colombia ............................................................................................................ 24 Guinea................................................................................................................. 37 Iraq/UK ............................................................................................................... 42 Nigeria ................................................................................................................ 47 Palestine .............................................................................................................. 53 Republic of the Philippines ................................................................................ 60 Ukraine ............................................................................................................... 66 IV. COMPLETED PRELIMINARY EXAMINATIONS ............................................ 74 Bangladesh/Myanmar ........................................................................................ -

Cocktails and Camels ALSO by JACQUELINE KLAT COOPER

Cocktails and Camels ALSO BY JACQUELINE KLAT COOPER FOR CHILDREN Angus and the Mona Lisa 1960 Toby and the Escalade 1997 Cat Day 1998 William Tell 1999 Kevin and the Escalade Race 2001 FOR ADULTS Tales from Alexandria 1994 Scribbles 2004 Le Crazy Cat Saloon 2005 You Never Know... Moments 2007 Cocktails and Camels Jacqueline Carol Bibliotheca Alexandrina Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cooper, Jacqueline. Cocktails and camels / Jacqueline Carol. – Alexandria, Egypt : Bibliotheca Alexandrina, c2008. p. cm. ISBN 978-977-452-115-7 1. Alexandria (Egypt) -- Social life and customs. 2. Cooper, Jacqueline -- Childhood and youth. I. Title 962.1053--dc21 2008375076 [This is an edited and condensed version of the original work published by Appleton- Century-Crofts, NY, 1960]. © Jacqueline Klate Cooper color sketch cover illustration, sketches pages 3 and 6 ISBN 978-977-452-115-7 Dar El Kuttub Depository No 7160/2008 © 2008 Bibliotheca Alexandrina. All Rights Reserved. NON-COMMERCIAL REPRODUCTION Information in this publication has been produced with the intent that it be readily available for personal and public non-commercial use and may be reproduced, in part or in whole and by any means, without charge or further permission from the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. We ask only that: • Users exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Bibliotheca Alexandrina be identified as the source; and • The reproduction is not represented as an official version of the materials reproduced, nor as having been made in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. COMMERCIAL REPRODUCTION Reproduction of multiple copies of materials in this publication, in whole or in part, for the purposes of commercial redistribution is prohibited except with written permission from the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. -

CREATING COCKTAILS Chef's Recipe on Course January Office

NEWSLETTER | JANUARY 2021 | PAGE 1 CREATING COCKTAILS From the Pro Shop Sunday, January 24th at 2:00 pm Prepaid Dues Come and join us for a mixology class where you will January Calendar learn how to make cocktails like a pro! You will make From the General Manager an Old Fashioned, The Winner, and a hot bourbon Earl Grey tea using top shelf liquor. Chef’s Recipe Appetizers and a bartending kit are included. Class A yummy dessert to keep you warm size is limited so reserve your spot before January 19th this month… by calling 235-5777 x4. Read More on Page 4 $85 per Couple $55 for Individual On Course What is the value of an irrigation system? Read More on Page 4 Happy Hour with January Office Hours Live Music Live music is back!!! The clubhouse will be closed from January 1st – 22nd. Office Join us on Friday, January hours will be limited during 29th for happy hour drink those weeks. Alena and specials and live music with Jennifer will be available Chad Lore. Chad will Monday – Friday from 9:00 am perform from 5 – 9 pm. to 1:00 pm so please plan accordingly if you need to stop Make your reservations by by or call for any reason. calling 235-5777 x1 NEWSLETTER | JANUARY 2021 | PAGE 2 FROM THE GENERAL MANAGER Happy New Year! I hope that everyone had a wonderful Christmas and holiday season. We can finally say goodbye to 2020 and looking forward to a new and exciting 2021. The club will be closed starting Jan 1st and reopen on Saturday, Jan 23rd. -

History of the Gay Rights Movement in America

History of the Gay Rights Movement in America Pre-Stonewall Beginning in colonial times there were prohibitions of sodomy derived from the English criminal laws passed in the first instance by the Reformation Parliament of 1533. The English prohibition was understood to include relations between men and women as well as relations between men and men. As Europeans settled in North America, they encountered Native American cultures which had different ideas about sexuality and gender. The accounts of French, Spanish and British travelers about Native American customs are full of references to such cultural differences, such as the acceptance among some groups of same-sex sexual activity and cross-dressing. Reactions to these differences ranged from amused to violent, as Europeans confronted cultures that did not follow what Europeans had always considered to be "natural" laws. European colonial governments sought to control the sexual behavior of the people within their settlements. The British, French, and Spanish all passed laws regarding sex outside of marriage and "sodomy" - a range of same-sex sexual activities. In early British colonies, as under English law, sodomy was a capital crime (punishable by death). One of the earliest recorded convictions for sodomy in the colonies was that of Richard Cornish, a sea captain executed in 1624 in Virginia for alleged homosexual acts with a servant. Despite the severity of the laws, however, we know of only a few instances of executions in sodomy cases during the colonial period. People were more likely to be tried for the lesser offense of "lewd behavior," which did not incur the death penalty. -

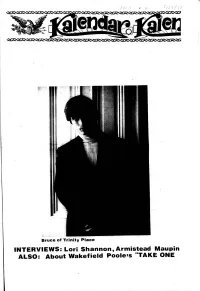

Lori Shannon, Armistead Maupin ALSO: About Wakefield Poole's

^ ■ ' Bruce of Trinity Place INTERVIEWS: Lori Shannon, Armistead Maupin ALSO: About Wakefield Poole’s "TAKE ONE SHOWTIME STEPPING OUT Ivkeii dickmi . ■'1 JunelO DEADLINE m o n d a » Jim e6| King and T", "L ittle Me" and "Bye, Bye NEXT ISi ■ix' Birdie. " Functional scenery that is f £ é r ^ idual states to maintain sexually re the earlier meetings. " eats another man's sperm. Sperm is simple, yet extremely colorful and Who’s on First pressive legislation. Describing that Specifically, NGTF urges lediians to the most concentrated form of blood. theatricaL decision as a federal precent that will get in touch with their state's IWY The homosexual is eating life. That's I wish Bibi Osteiwald had a funnier The crucial date for gays in Dade why God calls homosexuality an ab- part than that of Butler's aide, Dolly County, Fla, , is now June 7, On that adversely affect the lives of Gay peo coordinating committee (call or write ple for years to come, the May 21 Gay Jean for information if you can't track on^ation. " Taffe, but seeing her in person is great date a referendum will be held to de Asked whether heterosexual females for me. Art Lund as Buffalo Bill is very cide the fate of Miami's gay rights Action Coalition chose Saturday, May it down through other channels) and 21, to mark with outrage the first then (1) if possible become part of the who engage in oral sexual activities subtle in bringing more character to law passed by the County Commission are g u l^ of an abomination, Byrant in January, anniversary of the Court's ruling.