The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts: Production Department

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

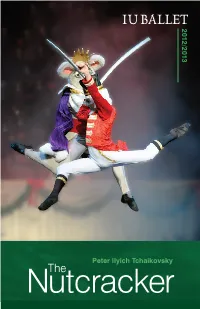

Nutcracker Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season ______Indiana University Ballet Theater Presents

2012/2013 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky NutcrackerThe Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents its 54th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story, “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffmann Michael Vernon, Choreography Andrea Quinn, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Designer Patrick Mero, Lighting Designer Gregory J. Geehern, Chorus Master The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, November Thirtieth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December First, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December First, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Second, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Doricha Sales, Children’s Ballet Mistress The children in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music’s Pre-College Ballet Program. Act I Party Scene (In order of appearance) Urchins . Chloe Dekydtspotter and David Baumann Passersby . Emily Parker with Sophie Scheiber and Azro Akimoto (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Maura Bell with Eve Brooks and Simon Brooks (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Maids. .Bethany Green and Liara Lovett (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Carly Hammond and Melissa Meng (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Tradesperson . Shaina Rovenstine Herr Drosselmeyer . .Matthew Rusk (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Gregory Tyndall (Dec. 1 mat.) Iver Johnson (Dec. -

Danc Scapes Choreographers 2015

dancE scapes Choreographers 2015 Amy Cain was born in Jacksonville, Florida and grew up in The Woodlands/Spring area of Texas. Her 30+ years of dance training include working with various instructors and choreographers nationwide and abroad. She has also been coached privately and been inspired for most of her dance career by Ken McCulloch, co-owner of NHPA™. Amy is in her 22nd year of partnership in directing NHPA™, named one of the “Top 50 Studios On the Move” by Dance Teacher Magazine in 2006, and has also been co-director of Revolve Dance Company for 10 years. She also shares her teaching experience as a jazz instructor for the upper level students at Houston Ballet Academy. Amy has danced professionally with Ad Deum, DWDT, and Amy Ell’s Vault, and her choreographic works have been presented in Italy, Mexico, and at many Houston area events. In June 2014 Amy’s piece “Angsters”, performed by Revolve Dance Company, was presented as a short film produced by Gothic South Productions at the Dance Camera estW Festival in L.A. where it received the “Audience Favorite” award. This fall “Angsters” will be screened on Opening Night at the San Francisco Dance Film Festival in California, and on the first screening weekend at the Sans Souci Festival of Dance Cinema in Boulder, Colorado. Dawn Dippel (co-owner) has been dancing most of her life and is now co-owner of NHPA™, co-Director and founding member of Revolve Dance Company, and a former member of the Dominic Walsh Dance Theatre. She grew up in the Houston area, graduated from Houston’s High School for the Performing & Visual Arts Dance Department, and since then has been training in and outside of Houston. -

PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016

For Immediate Release January 2016 PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016 Playhouse Square is proud to announce that the U.S. National Tour of ANNIE, now in its second smash year, will play January 12 - 17 at the Connor Palace in Cleveland. Directed by original lyricist and director Martin Charnin for the 19th time, this production of ANNIE is a brand new physical incarnation of the iconic Tony Award®-winning original. ANNIE has a book by Thomas Meehan, music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Martin Charnin. All three authors received 1977 Tony Awards® for their work. Choreography is by Liza Gennaro, who has incorporated selections from her father Peter Gennaro’s 1977 Tony Award®-winning choreography. The celebrated design team includes scenic design by Tony Award® winner Beowulf Boritt (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Rock of Ages), costume design by Costume Designer’s Guild Award winner Suzy Benzinger (Blue Jasmine, Movin’ Out, Miss Saigon), lighting design by Tony Award® winner Ken Billington (Chicago, Annie, White Christmas) and sound design by Tony Award® nominee Peter Hylenski (Rocky, Bullets Over Broadway, Motown). The lovable mutt “Sandy” is once again trained by Tony Award® Honoree William Berloni (Annie, A Christmas Story, Legally Blonde). Musical supervision and additional orchestrations are by Keith Levenson (Annie, She Loves Me, Dreamgirls). Casting is by Joy Dewing CSA, Joy Dewing Casting (Soul Doctor, Wonderland). The tour is produced by TROIKA Entertainment, LLC. The production features a 25 member company: in the title role of Annie is Heidi Gray, an 11- year-old actress from the Augusta, GA area, making her tour debut. -

Dance, American Dance

DA CONSTAANTLYN EVOLVINGCE TRADITION AD CONSTAANTLY NEVOLVINGCE TRADITION BY OCTAVIO ROCA here is no time like the Michael Smuin’s jazzy abandon, in present to look at the future of Broadway’s newfound love of dance, American dance. So much in every daring bit of performance art keeps coming, so much is left that tries to redefine what dance is behind, and the uncertainty and what it is not. American dancers Tand immense promise of all that lies today represent the finest, most ahead tell us that the young century exciting, and most diverse aspects of is witnessing a watershed in our country’s cultural riches. American dance history. Candid The phenomenal aspect of dance is shots of American artists on the that it takes two to give meaning to move reveal a wide-open landscape the phenomenon. The meaning of a of dance, from classical to modern dance arises not in a vacuum but in to postmodern and beyond. public, in real life, in the magical Each of our dance traditions moment when an audience witnesses carries a distinctive flavor, and each a performance. What makes demands attention: the living American dance unique is not just its legacies of George Balanchine and A poster advertises the appearance of New distinctive, multicultural mix of Antony Tudor, the ever-surprising York City Ballet as part of Festival Verdi influences, but also the distinctively 2001 in Parma, Italy. genius of Merce Cunningham, the American mix of its audiences. That all-American exuberance of Paul Taylor, the social mix is even more of a melting pot as the new commitment of Bill T. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Fall Repertoire 2020

Dance Department presents Fall Repertoire 2020 Artistic Director Chair of Dance Nancy Lushington Technical Director Philip Treviño Costume Coordinator/ Wardrobe Supervisor Production Sound Designer Mondo Morales Dan Cooper Historical Images (in sequence) Bill T Jones/Arnie Zane Company Blind Date 2005 Workers Theater Poster 1933 Pearl Primus Strange Fruit 1945 Maori Haka New Zealand (traditional) 1. PER TEMPUS Irish Dance Ensemble St Patrick’s Day Parade 2019 Choreographer Alberto del Saz Martha Graham Deep Song 1937 in collaboration with Dancers Kurt Jooss Green Table 1932 Music Daphnis 26 New Dance Group Open class 1933 Lindy Hop 1920s Composer Biosphere New Dance Group Poster 1932 Film Editing Alberto del Saz Vesta Tilley 1890’s Drag King Sound Design Dan Cooper Sankai Juku 2015 Bill T Jones and Arnie Zane Photo by Lois Greenfield 1981 Bill T Jones Body Paint by Keith Haring 1883 Dorrance Dance Elemental 2018 Taylor Mac 24 Decade History of Popular Music 2017 Alice Sheppard/Kinetic Light Descent 2019 Rennie Harris Funkedified 2019 Trisha Brown Walking on the Wall 1971 2. Rennie Harris Puremovement 2011 Dance and Civic Engagement Bill Shannon 2010 Facilitator Catherine Cabeen Camille A. Brown Ink 2017 Movement Meditation Written and Led by Lauren Aureus, Emily Dail, Molly Hefner, Todd Shalom & Niegel Smith Take Care 2016 Kayla Kemp, Heather Kroesche, Frankie New Orleans Highschool Dance for Change 2018 National Dance Institute Dream Project 2019 Levita, Kate Myers, Zion Newton, Remi Dance to be Free 2019 Rosenwald, Lily Sheppard, Payton -

Suddenly Mommy Program 2019

Suddenly Mommy merch available! Online at ClearlyBlonde.com Theatre INSERT NAME Presents Starring Remember The Leopard Written by Anne Marie Scheffler Print Robe from MILF Story Consultant Rosie Shuster Life Crisis? Production Design by Andy Moro Also available on www.- Original Song by Erinne White, Choreography by Nicola Pantin clearlyblonde.com Follow Anne Marie on Facebook! facebook.com/AnneMarieScheffler twitter @clearlyblonde instagram @annemariescheffler www.suddenlymommy.com Insert Date 2019 Suddenly Mommy! wrote many episodes of Square Pegs, as well as Bob and Margaret. She story edited CatDog, wrote screenplays for 6 of the major stu- Written & Performed by Anne Marie Scheffler dios including Warner Brothers and MGM. Rosie also produced many Story Consultant Rosie Shuster Carol Burnett Shows in the 90s, and a Superman's 50th Anniversary Production Design by Andy Moro Special. About Andy Moro About The Show Andy Moro has collaborated with companies including Native Earth Anne Marie Scheffler jumps into a new world of funny! Having kids! Performing Arts, Red Sky Performance, VideoCabaret, Topological Sure, she thought that’s what she always wanted, but they’re so Theatre, Cabaret Productions, Kaha:wi Dance Theatre, Buddies in much work! It looked so easy in the brochure! A mom in real life, Bad Times, Halfbreed Productions, da da kamera and more. Recent Scheffler exposes the truth of motherhood in an authentic and hilar- work includes Set and Lights for VideoCabaret’s War of 1812 at the ious way. She’ll make you feel good about your parenting skills! Stratford Festival, Set and Lights for Native Earth’s Free as Injuns, Projections for Kaha:wi’s Transmigration Set and Projections for About Anne Marie Scheffler* Kaha:wi’s Medicine Bear, Topological and YPT’s Beyond the Cuckoo’s Anne Marie is the writer and performer of 8 one woman shows, in- Nest, Waawaate Fobister’s AGOKWE and Red Sky’s Migrations at the cluding Situation: NORMA, Watch Norma’s Back, Leaving Norma, Dat- Banff Centre. -

Playbill Jan

UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST FINE ARTS CENTER 2012 Center Series Playbill Jan. 31 - Feb. 22 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Skill.Smarts.Hardwork. That’s how you built your wealth. And that’s how we’ll manage it. The United Wealth Management Group is an independent team of skilled professionals with a single mission: to help their clients fulfill their financial goals. They understand the issues you face – and they can provide tailored solutions to meet your needs. To arrange a confidential discussion, contact Steven Daury, CerTifieD fiNANCiAl PlANNer™ Professional, today at 413-585-5100. 140 Main Street, Suite 400 • Northampton, MA 01060 413-585-5100 unitedwealthmanagementgroup.com tSecurities and Investment Advisory Services offered through NFP Securities, Inc., Member FINRA/SIPC. NFP Securities, Inc. is not affiliated with United Wealth Management Group. NOT FDIC INSURED • MAY LOSE VALUE • NOT A DEPOSIT• NO BANK GUARANTEE NO FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AGENCY GUARANTEES 10 4.875" x 3.75" UMASS FAC Playbill Skill.Smarts.Hardwork. That’s how you built your wealth. And that’s how we’ll manage it. The United Wealth Management Group is an independent team of skilled professionals with a single mission: to help their clients fulfill their financial goals. They understand the issues you face – and they can provide tailored solutions to meet your needs. To arrange a confidential discussion, contact Steven Daury, CerTifieD fiNANCiAl PlANNer™ Professional, today at 413-585-5100. 140 Main Street, Suite 400 • Northampton, MA 01060 413-585-5100 unitedwealthmanagementgroup.com tSecurities and Investment Advisory Services offered through NFP Securities, Inc., Member FINRA/SIPC. -

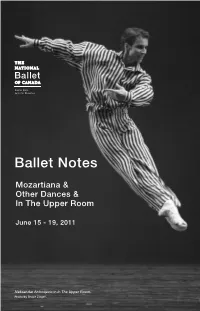

Ballet Notes

Ballet Notes Mozartiana & Other Dances & In The Upper Room June 15 - 19, 2011 Aleksandar Antonijevic in In The Upper Room. Photo by Bruce Zinger. Orchestra Violins Bassoons Benjamin BoWman Stephen Mosher, Principal Concertmaster JerrY Robinson LYnn KUo, EliZabeth GoWen, Assistant Concertmaster Contra Bassoon DominiqUe Laplante, Horns Principal Second Violin Celia Franca, C.C., Founder GarY Pattison, Principal James AYlesWorth Vincent Barbee Jennie Baccante George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Derek Conrod Csaba KocZó Scott WeVers Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Sheldon Grabke Artistic Director Executive Director Xiao Grabke Trumpets David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. NancY KershaW Richard Sandals, Principal Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk Mark Dharmaratnam Principal Conductor YakoV Lerner Rob WeYmoUth Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer JaYne Maddison Trombones Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Ron Mah DaVid Archer, Principal YOU dance / Ballet Master AYa MiYagaWa Robert FergUson WendY Rogers Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne DaVid Pell, Bass Trombone Filip TomoV Senior Ballet Master Richardson Tuba Senior Ballet Mistress Joanna ZabroWarna PaUl ZeVenhUiZen Sasha Johnson Aleksandar AntonijeVic, GUillaUme Côté*, Violas Harp Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, LUcie Parent, Principal Zdenek KonValina, Heather Ogden, Angela RUdden, Principal Sonia RodrigUeZ, Piotr StancZYk, Xiao Nan YU, Theresa RUdolph KocZó, Timpany Bridgett Zehr Assistant Principal Michael PerrY, Principal Valerie KUinka Kevin D. Bowles, Lorna Geddes, -

The Balanchine Trust: Dancing Through the Steps of Two-Part Licensing

Volume 6 Issue 2 Article 2 1999 The Balanchine Trust: Dancing through the Steps of Two-Part Licensing Cheryl Swack Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Cheryl Swack, The Balanchine Trust: Dancing through the Steps of Two-Part Licensing, 6 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 265 (1999). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol6/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Swack: The Balanchine Trust: Dancing through the Steps of Two-Part Licen THE BALANCHINE TRUST: DANCING THROUGH THE STEPS OF TWO-PART LICENSING CHERYL SWACK* I. INTRODUCTION A. George Balanchine George Balanchine,1 "one of the century's certifiable ge- * Member of the Florida Bar; J.D., University of Miami School of Law; B. A., Sarah Lawrence College. This article is dedicated to the memory of my mother, Allegra Swack. 1. Born in 1904 in St. Petersburg, Russia of Georgian parents, Georgi Melto- novich Balanchivadze entered the Imperial Theater School at the Maryinsky Thea- tre in 1914. See ROBERT TRAcy & SHARON DELONG, BALANci-NE's BALLERINAS: CONVERSATIONS WITH THE MUSES 14 (Linden Press 1983) [hereinafter TRAcY & DELONG]. His dance training took place during the war years of the Russian Revolution. -

East by Northeast the Kingdom of the Shades (From Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Music by Ludwig Minkus Staged by Glenda Lucena

2013/2014 La Bayadère Act II | Airs | Donizetti Variations Photo by Paul B. Goode, courtesy of the Paul Taylor Dance Company East by Spring Ballet Northeast Seven Hundred Fourth Program of the 2013-14 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents Spring Ballet: East by Northeast The Kingdom of the Shades (from Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Music by Ludwig Minkus Staged by Glenda Lucena Donizetti Variations Choreography by George Balanchine Music by Gaetano Donizetti Staged by Sandra Jennings Airs Choreography by Paul Taylor Music by George Frideric Handel Staged by Constance Dinapoli Michael Vernon, Artistic Director, IU Ballet Theater Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Patrick Mero, Lighting Design _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, March Twenty-Eighth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, March Twenty-Ninth, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, March Twenty-Ninth, Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Kingdom of the Shades (from Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Staged by Glenda Lucena Music by Ludwig Minkus Orchestration by John Lanchbery* Lighting Re-created by Patrick Mero Glenda Lucena, Ballet Mistress Violette Verdy, Principals Coach Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Premiere: February 4, 1877 | Imperial Ballet, Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, St. Petersburg Grand Pas de Deux Nikiya, a temple dancer . Alexandra Hartnett Solor, a warrior. Matthew Rusk Pas de Trois (3/28 and 3/29 mat.) First Solo. Katie Zimmerman Second Solo . Laura Whitby Third -

For Use by Media Beginning

Press Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Thursday, August 1, 2019 Bradley Cooper Tiffany Haddish Kevin Hart Trevor Noah Jon Stewart John Legend & Chrissy Teigen and Other Special Guests Celebrate the Humor of DAVE CHAPPELLE Recipient of the 22nd Annual Mark Twain Prize for American Humor in the Kennedy Center Concert Hall October 27, 2019 at 8 p.m. Program to be Broadcast Nationally on PBS January 6, 2020 at 9 p.m. (WASHINGTON)—A lineup of leading performers, including Bradley Cooper, Tiffany Haddish, Kevin Hart, Trevor Noah, Jon Stewart, John Legend & Chrissy Teigen, and others will salute Dave Chappelle at the 22nd annual Kennedy Center Mark Twain Prize for American Humor on Sunday, October 27, 2019 at 8 p.m. The program will pay tribute to the humor and accomplishments of Chappelle, and will be broadcasted on PBS stations on January 6, 2020. On-sale and ticketing information for this event will be available at a later date, and sponsorship packages and Party Passes for the Mark Twain Prize gala performance are on sale now. Capital One® is the Presenting Sponsor of this year’s Kennedy Center Mark Twain Prize for American Humor as part of the bank’s three-year, $3 million gift to fund Comedy at the Kennedy Center, a signature program at the Center focused on elevating comedy as an art form and uniting the community through laughter. The event will be co-chaired by Tamia and Grant Hill. The Mark Twain Prize for American Humor recognizes individuals who have had an impact on American society in ways similar to the distinguished 19th-century novelist and essayist Samuel Clemens, best known as Mark Twain.