Sample Copy. Not for Distribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Princely Palaces in New Delhi Datasheet

TITLE INFORMATION Tel: +1 212 645 1111 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.accartbooks.com/us Princely Palaces In New Delhi Sumanta K Bhowmick ISBN 9789383098910 Publisher Niyogi Books Binding Hardback Territory USA & Canada Size 9.18 in x 10.39 in Pages 264 Pages Price $75.00 The first-ever comprehensive book on the princely palaces in New Delhi Documentation based on extensive archival research and interviews with royal families Text supported by priceless photographs obtained from the private collections of the princely states, National Archives of India, state archives and various other government and private bodies Rajas and maharajas from all over the British Indian Empire congregated in Delhi to attend the great Delhi Durbar of 1911. A new capital city was born New Delhi. Soon after, the princely states came up with elaborate palaces in the new Imperial capital Hyderabad House, Baroda House, Jaipur House, Bikaner House, Patiala House, to name a few. Why did the British government allot prime land to the princely states and how? How did the construction come up and under whose architectural design? Who occupied these palaces and what were the events held? What happened to these palatial buildings after the integration of the states with the Indian Republic? This book delineates the story behind the story, documenting history through archival research, interviews with royalty and unpublished photographs from royal private collections. Contents: Foreword; The Journey; Living with History; Hyderabad House- Guests of Honour; Baroda House - Butterfly on the Track; Bikaner House -Rajasthan Royals; Jaipur House -An Acre of Art; Patiala House -Chambers of Justice; Travancore House -Hathiwali Kothi; Darbhanga House - The 'Twain Shall Meet; The Other Palaces - Scattered Petals; Planning the Palaces -Thy Will be Done; List of Princely Palaces. -

Rashtrapati Bhavan and the Central Vista.Pdf

RASHTRAPATI BHAVAN and the Central Vista © Sondeep Shankar Delhi is not one city, but many. In the 3,000 years of its existence, the many deliberations, decided on two architects to design name ‘Delhi’ (or Dhillika, Dilli, Dehli,) has been applied to these many New Delhi. Edwin Landseer Lutyens, till then known mainly as an cities, all more or less adjoining each other in their physical boundary, architect of English country homes, was one. The other was Herbert some overlapping others. Invaders and newcomers to the throne, anxious Baker, the architect of the Union buildings at Pretoria. to leave imprints of their sovereign status, built citadels and settlements Lutyens’ vision was to plan a city on lines similar to other great here like Jahanpanah, Siri, Firozabad, Shahjahanabad … and, capitals of the world: Paris, Rome, and Washington DC. Broad, long eventually, New Delhi. In December 1911, the city hosted the Delhi avenues flanked by sprawling lawns, with impressive monuments Durbar (a grand assembly), to mark the coronation of King George V. punctuating the avenue, and the symbolic seat of power at the end— At the end of the Durbar on 12 December, 1911, King George made an this was what Lutyens aimed for, and he found the perfect geographical announcement that the capital of India was to be shifted from Calcutta location in the low Raisina Hill, west of Dinpanah (Purana Qila). to Delhi. There were many reasons behind this decision. Calcutta had Lutyens noticed that a straight line could connect Raisina Hill to become difficult to rule from, with the partition of Bengal and the Purana Qila (thus, symbolically, connecting the old with the new). -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

Jahanpanah Fort, Delhi

Jahanpanah Jahanpanah Fort, Delhi Jahanpanah was a fortified city built by Muhammad bin Tughlaq to control the attacks made by Mongols. Jahanpanah means Refuge of the World. The fortified city has now been ruined but still some portions of the fort can still be visited. This tutorial will let you know about the history of the fort along with the structures present inside. You will also get the information about the best time to visit it along with how to reach the fort. Audience This tutorial is designed for the people who would like to know about the history of Jahanpanah Fort along with the interiors and design of the fort. This fort is visited by many people from India and abroad. Prerequisites This is a brief tutorial designed only for informational purpose. There are no prerequisites as such. All that you should have is a keen interest to explore new places and experience their charm. Copyright & Disclaimer Copyright 2017 by Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. All the content and graphics published in this e-book are the property of Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. The user of this e-book is prohibited to reuse, retain, copy, distribute, or republish any contents or a part of contents of this e-book in any manner without written consent of the publisher. We strive to update the contents of our website and tutorials as timely and as precisely as possible, however, the contents may contain inaccuracies or errors. Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. provides no guarantee regarding the accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of our website or its contents including this tutorial. -

Report 08-2021

India Gate, Delhi India Gate - The Pride of New Delhi A magnificent archway standing at the crossroads of Rajpath- the India Gate is a war memorial dedicated to the 70000 Indian soldiers who lost their lives in the First World War fighting on behalf of the allied forces. The erstwhile name of India gate is All India War Memorial. Architecture The India Gate was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, the English architect famous for planning a large part of New Delhi . His Royal Highness, the Duke of Connaught laid the foundation stone. Ten years later, Lord Irwin, the then Viceroy of India dedicated the India Gate to the nation. Lutyen was famous for combining classical architecture with traditional Indian elements. A remarkable instance of the classic arch of Lutyen's Delhi Order, the India Gate is a key symbol of New Delhi- the eighth city of Delhi. It bears a strong resemblance to the Arc de Triomphe in France. Though essentially a war memorial, the India Gate also borrows from the Mughal style of creating gateways. The India Gate stands on a base of red Bharatpur stone. The edifice itself is made of red sandstone and granite. An inverted interior dome appears on two square shaped trunks. Imperial signs are inscribed on the cornice. On both the sides of the arch is inscribed the word the word INDIA. The start and end dates of WWI appear on either side of the word. The columns are inscribed with the names of 13516 British and Indian soldiers who had died in the Northwestern Frontier in the Afghan war. -

Rajersh Mathur G 78A Lajpat Nagar Sahibabad , Ghaziabad Uttar Pradesh- 201005 7428066624 [email protected]

Rajersh Mathur G 78A Lajpat Nagar Sahibabad , Ghaziabad Uttar Pradesh- 201005 7428066624 [email protected] PERSONAL PROFILE Date of Birth : 20/03/1993 Marital Status : Single Nationality : Indian Known Languages : English, Hindi Hobby : Listening Music, Exploring Foods, Internet surfing CAREER OBJECTIVE To work innovatively for the enhancement and betterment of education and excel a professional teacher through integration of my knowledge and skills sets EDUCATION Year of Course Institute CGPA/Percentage Passing New Adarsh Institute of D.el.ed(also known as BTC) education , 2019 88.56 Ghaziabad affiliated by UP Scert Meerut College, CCS M.sc.(Chemistry) 2016 70.75 University Zakir Husain Delhi B.sc.(Physical Sciences) College, University 2014 64.50 of Delhi Govt.Sarvodaya Bal 12th Vidyalaya Delhi 2009 65.00 (CBSE) SVS Vidya Mandir 10th 2007 69.2 Ghaziabad (CBSE) CERTIFICATION CTET - Primary level Qualified CTET - Upper primary level Qualified UPTET -Primary Level Qualified UPTET -Upper Primary Level Qualified PROJECTS Innovation Project Awarded by University of Delhi "ZH-101" 12 months Feasibilty studies to improve quality of living and development of low cost efficient techniques to purify potable water: case study with reference to villages of Ajmer(Rajasthan) ACHIEVEMENTS & AWARDS Honoured by "Best Teacher Award 2019" by New Adarsh Institute of Education, Ghaziabad Honoured By "COLLEGE COLOUR AWARD" by Zakir Husain Delhi College, University Of Delhi Participated in the BEST CADET COMPETITION and Secure FIRST Position in College NCC Fest -

Annual Report 2018- 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2018- 2019 ZAKIR HUSAIN DELHI COLLEGE JAWAHAR LAL NEHRU MARG, NEW DELHI-110002 WEBSITE: www.zakirhusaindelhicollege.ac.in 011-23232218, 011-23232219 Fax: 011-23215906 Contents Principal’s Message ............................................................................................................................. 5 Coordinator’s Message ........................................................................................................................ 6 Co-ordinators of Annual Day Committees .......................................................................................... 7 Members of Annual Day Committees ................................................................................................. 8 Annual Report Compilation Committee ............................................................................................ 10 Reports of College Committees ......................................................................................................... 11 Memorial Lecture Committee ..................................................................................................... 12 Arts and Culture Society ............................................................................................................. 12 B. A. Programme Society ........................................................................................................... 16 Botany Society: Nargis ............................................................................................................... 16 -

List of Circle Wise Fatik

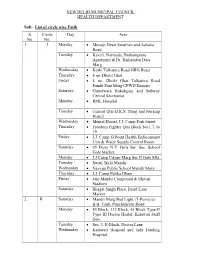

NEW DELHI MUNICIPAL COUNCIL HEALTH DEPARTMENT Sub:- List of circle wise Fatik S. Circle Day Area No. No. 1. I Monday Murarji Desai Sansthan and Ashoka Road. Tuesday Kaveri, Narmada, Brahamputra Apartment & Dr. Bishambar Dass Marg Wednesday Kothi Talkatora Road GRG Road Thursday 4 no. Dhobi Ghat Friday 4 no. Dhobi Ghat Talkatora Road Pandit Pant Marg CPWD Enquiry Saturday Gurudwara Rakabganj and Subway Central Secretariat Monday RML Hospital Tuesday Central Qtrs B.K.S. Marg and Nursing Hostel Wednesday Mental Hostel, J.J. Camp Park Street Thursday Freedom Fighter Qtrs Block No.1,7, to 19 Friday J.J. Camp G Point Health Enforcement Unit & Water Supply Control Room Saturday 95 Dairy N.P. Girls Ser. Sec. School Gole Market. Monday J.J Camp Udyan Marg Sec II Gole Mkt Tuesday Swati, Birla Mandir Wednesday Navyug Public School Mandir Marg Thursday J.J. Camp Palika Dham Friday Jain Mandir Compound & Shivaji Stadium Saturday Bhagat Singh Place, Baird Lane Market 2. II Saturday Mandir Marg Red Light (T-Point) to B.B. Tank, Punchkuiyan Road Monday 85 Block, 112 Block, 45 Block Type-II Type III Doctor Hostel, Kalawati Staff Qtrs. Tuesday Sec. 3, E-Block, Doctor Lane Wednesday Kalawati Hospital and lady Harding Hospital Thursday Gandhi Sadan, Avdh Vidhyalya to Palika Place Friday Block No.1 to 37 C Block, D Block, Sec-I R.K. Ashram marg Saturday Hanuman Mandir, Hanuman Road, Rgal Compound Monday Allahabad Bank, YMCA and YWCA Pragati Bhawan Jai Singh Road Tuesday Parliament Street Police Station, SBI Bank, Sardar Patel Bhawan Wednesday Connaught Place Turner, Palika Bazaar, Central Park Thursday Jeewan Bharti Building Janpath Road, Jantar mantar Road, Kerla House Friday N.P. -

Igl INDRAPRASTHA GAS LIMITED

SANSCO SERVlCf^Bknnual Rei »rar ces - www.sansco.net„ A N N U A L REPORT 2005-2006 Igl INDRAPRASTHA GAS LIMITED www.reportjunction.com SANSCO SERVICES - Annual Reports Library Services - www.sansco.net Board of Directors I I 2 I Report on Corporate Governance 13 Management Discussion and Analysis 2•3 Sat«Bi»SIMS«ii«i!*iaiiS!ias?SaS Auditors' Report •26 •BBB Balance Sheet •30 •BBB Profit and Loss Account •32 Cash flow Statement •34 •36 Balance Sheet Abstract and Company's •52 General Business Profile www.reportjunction.com BOARD OF DIRECTORS Shri Ashok Sinha Chairman ShriA.K. De Shri R.M. Gupta Shri R. Suresh Managing Director Director (Commercial) Director Shri S.S. Dalai Shri S.S. Rao ShriV.S. Madan Director Director Director Banker* Auditors Registered Office ICICI Bank Limited Canara Bank M/s BSR & Co. 14th & 15th Floor Corporate & Institutional Banking Division Jeevan Bharti Building, Tower-ll Chartered Accountants Dr. Gopal Das Bhawan 9A, Phelps Building, Connaught Place Parliament Street, New Delhi-110 001 Gurgaon 28, Barakhamba Road New Delhi-IIO 001 New Delhi-IIO 001 State Bank of India IDBI Bank Limited Corporate Accounts Group Branch 116, Sirifort Institutional Area I Ith Floor, jawahar Vyapar Bhawan Khel Gaon Marg, New Delhi-110 049 I Tolstox Marg, New Delhi-110 001 Company Secretary The Hongkong and Shanghai Bank of Baroda Shri S.K. Jain Banking Corporation Limited Ansal Chambers No. I Birla House, 25, Barakhamba Road Bhikaiji Cama Place New Delhi-110 001 New Delhi-IIO 066 www.reportjunction.com DIRECTORS' REPORT To, FINANCIAL RESULTS THE MEMBERS (Rs. -

The Architecture of Democracy

TIF - The Architecture of Democracy PREM CHANDAVARKAR September 4, 2020 Central Vista, New Delhi: The North and South blocks of Rashtrapati Bhavan lit for Republic Day | Namchop (CC BY-SA 3.0) The imperial Central Vista in Delhi has been transformed since 1947 into a symbol of democratic India. But the proposed redevelopment will reduce public space, highlight the spectacle of government and seems to reflect the authoritarian turn in our democracy. The Government of India is proposing a radical reshaping of the architecture and landscape of New Delhi’s Central Vista: a precinct that is the geographical heart of India’s democracy containing Parliament, ministerial offices, the residence and office of the President of India, major cultural institutions, and a public landscape that is beloved to the residents of Delhi and citizens of India. Its design originally came into being in 1913-14 as a British creation meant to mark imperial power in India through a new capital city in Delhi. After Independence, its buildings and spaces have been appropriated by Indians. How was the original design meant to serve as a public symbol of imperial power and governance? In the seven plus decades since Independence, how has it been appropriated by Indians such that during those decades it has Page 1 www.TheIndiaForum.in September 4, 2020 become an integral part of the independent nation’s history, leading to the precinct and its major edifices receiving the highest listing of Grade-1 from the Heritage Conservation Committee, Delhi? And what light does the currently planned redevelopment throw on the direction that contemporary India’s governance is taking, especially in reference to its equation with the general public? To understand these questions in their full depth, we must examine the history of how city form has visually reflected political ideals of governance. -

Republic Day to Get Many Firsts, Dhanush and the Anti

Fri, 24 Jan 2020 Republic Day to get many firsts, Dhanush and the Anti Satellite missile to be part of parade Three army equipment are being displayed for the first time during the parade, Major General Alok Kacker, the Chief of Staff Delhi Area, who is the parade’s second-in-command said. The main attraction out of the three would be the Dhanush artillery gun. The Dhanush is a 155mm calibre artillery gun, which has been developed by the OFB By Shaurya Karanbir Gurung New Delhi: The ceremonial wreath laying by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Republic Day on Sunday will be held for the first time at the National War Memorial, instead of at the Amar Jawan Jyoti. This will also be the first time that the recently appointed Chief of Defence Staff General Bipin Rawat will be part of this ceremony. The CDS along with Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, the Minister of State for Defence Shripad Yesso Naik, the three services chiefs and the Defence Secretary Ajay Kumar will be standing behind the Prime Minister according to the laid down protocol. Previously, the wreath laying ceremony followed by a salute by the dignitaries during Republic Day was held at the Amar Jawan Jyoti, located under the arch of India Gate. The change this time doesn’t mean that the Amar Jawan Jyoti will be ignored. Officials said that a wreath will be laid there as well on Republic Day. There will also be other firsts. The Dhanush artillery gun and the Anti-Satellite missile will be part of the Republic Day parade for the first time this year. -

Sainik 1-15 December Covers

In This Issue Since 1909 AwardBIRTH of President’s ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS Standard to 223 4 Squadron and 117 Helicopter Unit (Initially published as FAUJI AKHBAR) Vol. 64 q No 23 10 - 24 Agrahayana, 1939 (Saka) 1-15 December 2017 The journal of India’s Armed Forces published every fortnight in thirteen languages including Hindi & English on behalf of Ministry of Defence. It is not necessarily an organ for the expression of the Government’s defence policy. The published items represent the views of respective writers and correspondents. Editor-in-Chief Hasibur Rahman Senior Editor Ms Ruby T Sharma Joint Statement by Smt 6 A Special Campaign to Editor Ehsan Khusro Nirmala Sitharaman… celebrate Armed… 7 Sub Editor Sub Maj KC Sahu Production Officer Ramesh Ram Coordination Kunal Kumar Business Manager Rajpal Our Correspondents DELHI: Col Aman Anand; Capt DK Sharma VSM; Wg Cdr Anupam Banerjee; Manoj Tuli; Nampibou Marinmai; Ved Pal; Divyanshu Kumar; Photo Editor: K Ramesh; ALLAHABAD: Gp Capt BB Pande; BENGALURU: Guruprasad HL; CHANDIGARH: Anil Gaur; CHENNAI: T Shanmugam; GANDHINAGAR: Wg Cdr Abhishek Matiman; GUWAHATI: Lt Col Suneet Newton; IMPHAL: Lt Col Ajay Kumar Sharma; JALANDHAR : Anil Gaur; JAMMU: Col NN Joshi; 8 Dr Bhamre inaugurates 2nd... JAIPUR: Lt Col Manish Ojha; KOCHI: Cdr Sridhar E Warrier ; KOHIMA: Col 42nd ICMM World Chiranjeet Konwer; KOLKATA: Wg Cdr SS Birdi; Dipannita Dhar; LUCKNOW: 9 Military honours to two WW-I… Ms Gargi Malik Sinha; MUMBAI: Cdr Rahul Sinha; Narendra Vispute; NAGPUR: 10 237 Glorious years of Corps of… Congress on Military… 14 Wg Cdr Samir S Gangakhedkar; PUNE: Mahesh Iyengar; SECUNDERABAD: 18 NCC Gujarat at Beyt Dwarka G Surendra Babu; SHILLONG; Lt Col Suneet Newton; SRINAGAR: Col Rajesh 19 ASC Motorcycle Display team… Kalia; TEZPUR: Lt Col Sombit Ghosh; THIRUVANANTHAPURAM: Ms Dhanya Sanal K; UDHAMPUR: Col NN Joshi; VISAKHAPATNAM: Cdr CG Raju.