District Human Development Report SANGRUR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

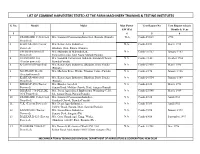

List of Combine Harvester Updated in July 2016

LIST OF COMBINE HARVESTERS TESTED AT THE FARM MACHINERY TRAINING & TESTING INSTITUTES S. No. Model Make Max Power Test Report No Test Report release kW (Ps) Month & Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 STANDARD C-514 (Self M/s. Standard Corporation India Ltd., Barnala (Punjab) N.A. Comb-29/615 1992 Propelled) 2 KARTAR-350 (Tractor M/s. Kartar Agro Industries, N.A. Comb-2/151 March 1975 Powered) Bhadson, Distt. Patiala (Punjab) 3 SWARAJ-8100 (Self M/s. Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd., N.A. Comb-18/357 January 1983 Propelled) Swaraj Diviision, SAS Nagar,Mohali(Punjab) 4 STANDARD 365 M/s. Standard Corporation IndiaLtd.,Standard Chowk, N.A. Comb-1/140 October 1984 (Tractor powered) Barnala(Punjab) 5 K-3500 (Self Propelled) M/s. Kartar Agro Industries, Bhadson, Distt. Patiala N.A. Comb-21/438 March 1985 (Punjab) 6 MATHARU M-350 M/s. Matharu Engg. Works, Firozpur Cantt. (Punjab) N.A. Comb-3/174 January 1986 (TractorPowered) 7 KARTAR-4000 (Self M/s. Kartar Agro Industries, Bhadson, Distt. Patiala N.A. Comb-24/534 January 1989 Propelled) (Punjab) 8 BHODAY 470 (Tractor M/s. Bhodey Agro Ltd N.A. Comb-4/350 March 1991 Powered) Sunam Road, Mehlan Chowk, Distt. Sangrur(Punjab) 9 BHARAT 730 DELUXE M/s. Jiwan Agricultural Implements Workshop C.I.S. N.A. Comb-25/540 March 1989 (Self Propelled) ltd., Sanaur Road, Patiala(Punjab) 10 STANDARD C-412 (Self M/s. Standard Corporation IndiaLtd., N.A. Comb-6/386 April 1992 Propelled) Standard Chowk, Barnala(Punjab) 11 V.K. (Tractor Powered) M/s. -

Dr. Shahila Zafar

Dr. Shahila Zafar Assistant Professor Department of Languages and Comparative Literature , School of Language, Literature and Culture Central University of Punjab, Bathinda, India , 151001 [email protected] ; [email protected] ; +91 - 9952112920 RESEARCH AND TEACHING INT E RESTS Applied Linguistics, Second Language Acquisition, Language Learning and Technology , English Language Teaching , African - American Literature , Indian Writing in English EDUCA T ION 2012 Ph.D. , Applied Linguistics , VIT University, Vellore , Tamil Nadu, India Advisor: Dr. K. Meenakshi Thesis Topic: Relationship between English Language Proficiency and Extrav ersion – Introversion Tendencies among University Level Chinese Students 2008 M.Phil. English, Madurai Kamraj University, Madurai , Tamil Nadu, India 2001 M . A . English , Punjabi University, Patiala , Punjab, India 1999 B . A . English ( Hons.) , Government College for Girls, Punjabi University Patiala , Punjab, India NON - DEGREE COURSES Courses completed at the Five Colleges, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA , 2016 - 17 1. Language Method - Colloquium 4. Broadcast News Reporting 2. Language Method - Practicum 5. Black Women Writers 3. Translation and Technology QUALIFYING EXAMS CLEARED 2001 - UGC (NET) - University Grants Commission’s National Eligibility Test for Lectureship in Engl ish Conducted by UGC, New Delhi, India. 2001 - State Level Eligibility Test (SLET) for Lectureship in English, conducted by Rajasthan Public Service Commission, Rajasthan, India TEACHING Assistant -

Administrative Atlas , Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 PUNJAB ADMINISTRATIVE ATLAS f~.·~'\"'~ " ~ ..... ~ ~ - +, ~... 1/, 0\ \ ~ PE OPLE ORIENTED DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, PUNJAB , The maps included in this publication are based upon SUNey of India map with the permission of the SUNeyor General of India. The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of twelve nautical miles measured from the appropriate base line. The interstate boundaries between Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Meghalaya shown in this publication are as interpreted from the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971 but have yet to be verified. The state boundaries between Uttaranchal & Uttar Pradesh, Bihar & Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh & Madhya Pradesh have not been verified by government concerned. © Government of India, Copyright 2006. Data Product Number 03-010-2001 - Cen-Atlas (ii) FOREWORD "Few people realize, much less appreciate, that apart from Survey of India and Geological Survey, the Census of India has been perhaps the largest single producer of maps of the Indian sub-continent" - this is an observation made by Dr. Ashok Mitra, an illustrious Census Commissioner of India in 1961. The statement sums up the contribution of Census Organisation which has been working in the field of mapping in the country. The Census Commissionarate of India has been working in the field of cartography and mapping since 1872. A major shift was witnessed during Census 1961 when the office had got a permanent footing. For the first time, the census maps were published in the form of 'Census Atlases' in the decade 1961-71. Alongwith the national volume, atlases of states and union territories were also published. -

(OH) Category 1 14 Muhammad Sahib Town- Malerkotla, Distt

Department of Local Government Punjab (Punjab Municipal Bhawan, Plot No.-3, Sector-35 A, Chandigarh) Detail of application for the posts of Beldar, Mali, Mali-cum-Chowkidar, Mali -cum-Beldar- cum-Chowkidar and Road Gang Beldar reserved for Disabled Persons in the cadre of Municipal Corporations and Municipal Councils-Nagar Panchayats in Punjab Sr. App Name of Candidate Address Date of Birth VH, HH, No. No. and Father’s Name OH etc. Sarv Shri/ Smt./ Miss %age of disability 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 14 Muhammad Sahib Town- Malerkotla, Distt. 01.10.1998 OH 50% S/o Muhammad Shafi Sangrur 2 54 Harjinder Singh S/o Vill. Kalia, W.No.1, 10.11.1993 OH 55% Gurmail Singh Chotian, Teh. Lehra, Distt. Sangrur, Punjab. 3 61 Aamir S/o Hameed W.No.2, Muhalla Julahian 08.11.1993 OH 90% Wala, Jamalpura, Malerkotla, Sangrur 4 63 Hansa Singh S/o Vill. Makror Sahib, P.O. 15.10.1982 OH 60% Sham Singh Rampura Gujjran, Teh. Moonak, Distt. Sangrur, Punjab. 5 65 Gurjant Singh S/o Vill. Kal Banjara, PO Bhutal 02.09.1985 OH 50% Teja Singh Kalan, Teh. Lehra, Distt. Sangrur 6 66 Pardeep Singh S/o VPO Tibba, Teh. Dhuri, 15.04.1986 OH 60% Sukhdev Singh Distt. Sangrur 7 79 Gurmeet Singh S/o # 185, W. No. 03, Sunam, 09.07.1980 OH 60% Roshan Singh Sangrur, Punjab. 8 101 Kamaljit Singh S/o H. No.13-B, Janta Nagar, 09.08.1982 OH 90% Sh. Charan Singh Teh. Dhuri, Distt. -

1. a Person with Good Communication Skill, Well Versed with Banking Operations, Having a Passion for Service to Financially Excluded People Will Be Given Preference

आँचलिक कार्ाािर् ,रजबाहा रो蔼,पटिर्ािा /ZONAL OFFICE, RAJBAHA ROAD, PATIALA – 147001 फोन न/.Phone No.: 0175-5030779,7771 फै啍स न/. Fax: 0175-2215427 ई/लेम- E-mail:[email protected] Applications are invited for the post of Financial Literacy Counsellors in Punjab & Sind Bank at Block Bhawanigarh Distt Sangrur Block Dirba Distt Sangrur & Block Bhunerehri Distt Patiala Retired Bank Officials from Public Sector Banks (Scale II and above) below the age of 65 years and in good health are eligible to apply for the post. Other Terms and Condition:- 1. A Person with good communication skill, well versed with Banking operations, having a passion for service to financially excluded people will be given preference. 2. The services of FLC Counsellors will be hired for 12 months on contract basis subject to renewal every year on recommendation of concerned Zonal Manager till they attain the age of 65 years. However, Competent Authority shall have the right to terminate the contract by giving 30 days prior notice. 3. Candidates from the same District will be preferred. However, Zonal Manager may recommend names of the candidates from adjoining District also which are very near to FLC Centre. 4. The shortlisted candidates will be considered for hiring subject to vigilance clearance from the concerned Bank/s. 5. Bank will not consider any candidate who is dismissed from service or given CRS or major penalty during last five years of his service. 6. FLC Counsellor will be paid a fixed consolidated remuneration of Rs.12,000/- per month plus reimbursement of actual conveyance expenses up to Rs. -

List of Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal

LIST OF PUNJAB PRADESH CONGRESS SEVA DAL CHIEF ORGANISER 1. Shri Nirmal Singh Kaira Chief Organiser Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Kira Property Dealer 2322/1, Basti Abdulpur Dist- Ludhiana, Punjab Tel:0161-2423750, 9888183101 07986253321 [email protected] Mahila Organiser 2 Smt. Mukesh Dhariwal Mahila Organiser Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal, H.No.32, Pritam Park Ablowal Road, District- Patiala Punjab Tel-09417319371, 8146955691 1 Shri Manohar Lal Mannan Additional Chief Organiser Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Prem Street,Near Police Station Cheharta Dist- Amritsar Punjab Tel: 0183-2258264, 09814652728 ORGANISER 1 Shri Manjit Kumar Sharma 2. Mrs. Inder Mohi Organiser Organiser Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Sharma House Sirhind House No- 4210, Street No-10 Ward No- 15, G.T. Road Bara Guru Arjun Dev Nagar Sirhind, Fatehgarh Sahib Near Tajpur Road Punjab Dist- Ludhiana(Punjab) Tel: 01763- 227082, 09357129110 Tel: 0161-2642272 3 Shri Surjit Singh Gill 4 Shri Harmohinder Singh Grover Organiser Organiser Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal C.M.C. Maitenary Hospital Street No-5, New Suraj Nagari Ludhiana(Punjab) Abohar Tel: 09815304476 Punjab Tel-09876867060 5 Shri Thakur Saheb Singh 6 Shri S. Gurmail Singh Brar Organiser Organiser Punjab Pradesh Cong.Seva Dal Punjab Pradesh Congress Seva Dal House No-M-163, Phase-7 190, New Sunder Nagar , Mohali Po –Thricko Dist- Ropar(Punjab) Dist- Ludhiana(Punjab) Tel: 9417040907 Tel: 0161- 255043, 9815650543 7 Smt. Leela -

Punjab 5% Sample Check(2007-08).Pdf

Chapter 1 Experience Summary Introduction With an aim to move towards Knowledge based society, efforts are being made to provide education to all in the age group of 6 – 14 years of age. Government has launched schemes and provided frame works to state to implement the schemes keeping state needs in mind. The common objective is to reach out to all children in this age group, enrol them in some or other system of education. This mammoth task is to be achieved by 2010. The community role and involvement has been specified. They are playing different roles in different management run schools. Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan is one such scheme. The thrust is on total retention of all children in schools. Within this framework it is expected that the education system will be made relevant so that children and parents find the schooling system contributing in all round development of the child and they find it useful and and relevant to their natural and social environment. There was a provision for Information System so as to monitor the qualitative and qualitative growth of the program . An effective system for generating the data for different levels of planners, managers and policy planners was introduced. A pool of resource persons was to be created at district and state level to gather data and computerize it. Education Management Information System (EMIS) EMIS is a formal method of providing educational managers with accurate and timely information so that decision making, planning, project development and implementation and other management functions and operations can be carried out effectively. -

Police Station.Pdf

LIST OF POLICE STATIONS ALLOTED TO THE ADDITIONAL DISTRICT & SESSIONS JUDGES UNDER THE NDPS ACT (NO.61 OF 1985) POSTED IN SANGRUR SESSIONS DIVISION (as on 09 August 2021) Sr. No. Name of Judicial Officer Designation Name of Police Station 1 Ms. Baljinder Siddhu ASJ City Sangrur, GRP Sangrur and City-1 Sangrur 2 Sh. Baljinder Singh-II ASJ Longowal and Sadar Sangrur 3 Sh. Sham Lal ASJ City / Sadar Sunam, Moonak and Dirba 4 Ms. Saru Mehta Kaushik ASJ Cheema, Khanauri, Bhawanigarh and Chajli City Dhuri, City / Sadar Ahmedgarh, Sadar 5 Ms. Smriti Dhir ASJ Dhuri and Sherpur City / Sadar Amargarh, Sandaur,Dharmgarh and 6 Ms. Girish ASJ City Malerkotla-2 7 Sh. Gurpartap Singh ASJ City-1 Malerkotla and Lehra LIST OF POLICE STATIONS ALLOTED TO THE JUDICIAL MAGISTRATES POSTED IN SANGRUR SESSIONS DIVISION Sr. No. Name of Judicial Officer Designation Name of Police Station Sadar Sangrur, Police Post Channo, Bhawanigarh 1 Sh. Ajit Pal Singh-II CJ(SD) and Police Post Gharachon City Sangrur,Vigilance Bureau Patiala, RPF, 2 Sh. Harvinder Singh Sindhia CJM GRP and NRI Sangrur 3 Sh. Rahul Kumar ACJ(SD) Longowal and Police Post Badrukhan 4 Sh. Amrish Kumar Jain CJ(JD) Exclusive Court 138 NI ACT and City 1 Sangrur DHURI Sr. No. Name of Judicial Officer Designation Name of Police Station 1 Ms. Neha Goel ACJ(SD) City Dhuri and GRP 2 Ms. Lavleen Sandhu CJ(JD) Sherpur and Sadar Dhuri SUNAM Sr. No. Name of Judicial Officer Designation Name of Police Station 1 Ms. Amandeep Kaur-I ACJ(SD) City / Sadar Sunam and Cheema Ms. -

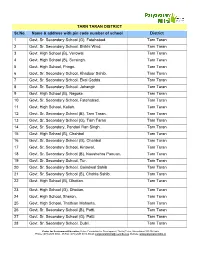

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

Census of India 2011

Census of India 2011 PUNJAB SERIES-04 PART XII-B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK TARN TARAN VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS PUNJAB CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 PUNJAB SERIES-04 PART XII - B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK TARN TARAN VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations PUNJAB MOTIF GURU ANGAD DEV GURUDWARA Khadur Sahib is the sacred village where the second Guru Angad Dev Ji lived for 13 years, spreading the universal message of Guru Nanak. Here he introduced Gurumukhi Lipi, wrote the first Gurumukhi Primer, established the first Sikh school and prepared the first Gutka of Guru Nanak Sahib’s Bani. It is the place where the first Mal Akhara, for wrestling, was established and where regular campaigns against intoxicants and social evils were started by Guru Angad. The Stately Gurudwara here is known as The Guru Angad Dev Gurudwara. Contents Pages 1 Foreword 1 2 Preface 3 3 Acknowledgement 4 4 History and Scope of the District Census Handbook 5 5 Brief History of the District 7 6 Administrative Setup 8 7 District Highlights - 2011 Census 11 8 Important Statistics 12 9 Section - I Primary Census Abstract (PCA) (i) Brief note on Primary Census Abstract 16 (ii) District Primary Census Abstract 21 Appendix to District Primary Census Abstract Total, Scheduled Castes and (iii) 29 Scheduled Tribes Population - Urban Block wise (iv) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes (SC) 37 (v) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Tribes (ST) 45 (vi) Rural PCA-C.D. blocks wise Village Primary Census Abstract 47 (vii) Urban PCA-Town wise Primary Census Abstract 133 Tables based on Households Amenities and Assets (Rural 10 Section –II /Urban) at District and Sub-District level. -

Proclaimed Offenders

Sheet2 LIST OF PROCLAIMED OFFENDERS Sr. Date of Date of CNR No. Case No. Case Title Particulars of P.O. FIR No. Date Under Section Police Station Court Name No. Instt. Order Om Parkash Village Dhakana Kalan 1 PBPTA10040742017 COMA/672/2017 09/05/17 Mahesh Kumar Vs Om Parkash NA 138 NA 17/08/18 Ms. Karandeep kaur JMIC Rajpura Tehsil Rajpura 1. SUNIL KUMAR H.NO. 381 GURU PARWINDER SINGH VS SUNIL ANGAD DEV COLONY RAJPURA 2. 2 PBPTA10009012015 COMA/438/2015 07/09/15 NA 138 NA 15/11/17 Ms. Karandeep kaur JMIC Rajpura KUMAR BHUPINDER KUMAR H.NO. 381 GURU ANGAD DEV COLONY RAJPURA ROHIT MUNJAL VS. NARESH NARESH KUMAR. 1539 NEAR MAHAVIR 3 PBPTA10027592017 COMA/480/2017 07/11/17 NA 138 NA 17/08/18 Sh. Abhinav kiran Sekhon ,JMIC, Rajpura KUMAR MANDIR WARD NO 22 RAJPURA Sukhdev Kumar New Dhiman Furniture 4 PBPT030007622018 COMA/329/2018 01/17/18 Vikas sood vs Sukhdev Kumar NA 138 NA 18/08/18 Ms. Neha Goel ,JMIC Patiala. Gaijukhera Rajpura STATE V/S NADEEM KHAN PS MANDI 13 GAMBLING P.S URBAN ESTATE 5 PBPT03-000966-2014 Cha/44/2014 02/11/14 171/2013 30/07/14 SH.RAMAN KUMAR,ACJM,PATIALA . NADEEM KAHN MUJAFARNAGAR U.P Act , PATIALA DHARMINDER SINGH @ MANGA S/O 336,427,419,420 CIVIL LINES 6 PBPT03-000586-2014 CHA/54/2014 7-6-2014 STATE VS PARDEEP KUMAR SURJIT SINGH R/O VILL NIJARA,DIST 305/16-11-13 8-7-2016 MS.NIDHI SAINI,JMIC,PATIALA. ,467,IPC PATIALA JALANDHAR RAJAT GARG S/O RAKESH GARG R/O CIVIL LINES 7 PBPT03002260-2017 CHI36/2017 5-4-2017 STATE VS NISHANT GARG 251/19-11-16 406,420 IPC 16-8-2018 MS.NIDHI SAINI,JMIC,PATIALA.