2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act: Challenges and Opportunities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

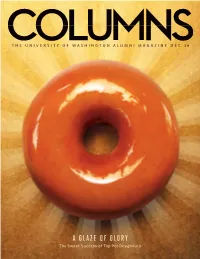

A GLAZE of GLORY the Sweet Success of Top Pot Doughnuts JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE

THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON ALUMNI MAGAZINE DEC 1 4 A GLAZE OF GLORY The Sweet Success of Top Pot Doughnuts JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE 20 ADVANCED DEGREES + 50 CERTIFICATES + 100S OF COURSES AEROSPACE ENGINEERING // PUBLIC HEALTH // C# // APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT BIOSTATISTICS // COMPUTATIONAL FINANCE // MANAGEMENT // PROGRAMMING BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT // INFORMATION SECURITY ANALYTICS // GIS // DATA VISUALIZATION // SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORTATION RUBY // RISK MANAGEMENT // BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE // INFORMATION SYSTEMS PROJECT MANAGEMENT // CONTENT STRATEGY // ORACLE DATABASE ADMIN LOCALIZATION // PARALEGAL // MACHINE LEARNING // SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS BEHAVIORAL HEALTH // GERONTOLOGY // BIOTECHNOLOGY // CIVIL ENGINEERING DEVOPS // DATA SCIENCE // MECHANICAL ENGINEERING // HEALTH CARE // HTML CONTENT STRATEGY // EDUCATION // PROJECT MANAGEMENT // INFORMATICS STATISTICAL ANALYSIS // E-LEARNING // CLOUD DATA MANAGEMENT // EDITING C++ // INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING // LEADERSHIP // BIOSCIENCE // LINGUISTICS INFORMATION SCIENCE // AERONAUTICS & ASTRONAUTICS // APPLIED MATHEMATICS CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING // GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS // PYTHON UW ONLINE 2 COLUMNS MAGAZINE ONLINE.UW.EDU JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE 20 ADVANCED DEGREES + 50 CERTIFICATES + 100S OF COURSES AEROSPACE ENGINEERING // PUBLIC HEALTH // C# // APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT BIOSTATISTICS // COMPUTATIONAL FINANCE // MANAGEMENT // PROGRAMMING BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT // INFORMATION SECURITY ANALYTICS // GIS // DATA VISUALIZATION // -

Focus Winter 2007 12

12 FOCUS WINTER 2007 the Broncos’ EPIC JOURNEY It started in December 2005 with Chris Petersen’s promotion from offensive coordina- tor to head coach and ended on New Year’s Day 2007 with a stunning and astounding 43-42 overtime win over Oklahoma in the Fiesta Bowl (pictured). FOCUS looks back at the 2006 Boise State football team’s 13-0 storybook season. (John Kelly photo) FOCUS WINTER 2007 13 yes, IT REALLY HAPPENED By Bob Evancho At times, it still seems surreal — as if what we watched unfold on the evening of New Year’s Day didn’t really happen: Did we just tie the game on fourth-and-18 from the 50 with seven seconds left? Did Vinny just hit “Shoe” with that TD pass? DID IAN REALLY JUST SCORE ON A STATUE OF LIBERTY TO WIN THE GAME?! MAGIC MOMENTS Ian Johnson races to the end zone for the game-winning 2-point conversion against Oklahoma as guard Jeff Cavender (64) watches. Opposite page top: Fiesta Bowl Defensive MVP Marty Tadman rejoices in the PHOTOS JOHN KELLY victory. Bottom: Quarterback Jared Zabransky hoists the Offensive MVP award. 14 FOCUS WINTER 2007 y now, we all know it wasn’t a dream. And by now, the adjectives B to describe that win and those moments have been exhausted. Weeks later, Bronco Nation has come back down to Earth. Since Boise State’s sublime 43-42 overtime win over Oklahoma in the Tostitos Fiesta Bowl, the mood of the Boise State faithful has slowly changed from unfettered exuberance to warm contentment, the kind that lasts for months. -

PPWG Agenda Interim Mtg Spring 21.Docx

Date: 3/23/21 Virtual Meeting (in lieu of meeting at the 2021 Spring National Meeting) PRIVACY PROTECTIONS (D) WORKING GROUP Monday, March 29, 2021 4:00 – 5:00 p.m. ET / 3:00 – 4:00 p.m. CT / 2:00 – 3:00 p.m. MT / 1:00 – 2:00 p.m. PT ROLL CALL Cynthia Amann, Chair Missouri Martin Swanson Nebraska Ron Kreiter, Vice Chair Kentucky Chris Aufenthie/Johnny Palsgraaf North Dakota Damon Diederich California Raven Collins/Brian Fordham Oregon Erica Weyhenmeyer Illinois Gary Jones Pennsylvania LeAnn Crow Kansas Don Beatty/Katie Johnson Virginia T.J. Patton Minnesota NAIC Support Staff: Lois E. Alexander AGENDA 1. Consider Adoption of its 2020 Fall National Meeting Minutes Attachment A —Cynthia Amann (MO) 2. Receive Status Reports—Cynthia Amann (MO) a. Federal Privacy Legislation—Brooke Stringer (NAIC) b. State Privacy Legislation—Jennifer McAdam (NAIC) Attachments B and C 3. Review the 2021 NAIC Member-Adopted Strategy for Consumer Data Privacy Attachment D Protections—Cynthia Amann (MO) 4. Discuss Comments Received on 2020 Fall National Meeting Verbal Gap Analysis a. American Council of Life Insurers (ACLI) —Robert Neill (ACLI) Attachment E b. Coalition of Health Carriers—Chris Petersen (Arbor Strategies LLC) Attachment F c. National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies (NAMIC) Attachment G —Cate Paolino (NAMIC) d. American Property Casualty Insurance Association (APCIA) Attachment H —Angela Gleason (APCIA) 5. Announce the Consumer Privacy Protections Panel at the NAIC Virtual Insurance Summit, June 14–21, 2021—Cynthia Amann (MO) 6. Discuss Any Other Matters Brought Before the Working Group—Cynthia Amann (MO) 7. Adjournment W:\National Meetings\2021\Spring\Cmte\D\Privacy Protections\PPWG Agenda Interim Mtg Spring 21.Docx 1 Attachment A Privacy Protections (D) Working Group 3/29/21 Draft: 12/1/20 Privacy Protections (D) Working Group Virtual Meeting (in lieu of meeting at the 2020 Fall National Meeting) November 20, 2020 The Privacy Protections (D) Working Group of the Market Regulation and Consumer Affairs (D) Committee met Nov. -

Colby Alumnus Vol. 75, No. 1: December 1985

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Colby Alumnus Colby College Archives 1986 Colby Alumnus Vol. 75, No. 1: December 1985 Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Colby College, "Colby Alumnus Vol. 75, No. 1: December 1985" (1986). Colby Alumnus. 132. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus/132 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Alumnus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. DECEM BER 1985 THE ALU M NUS 10 12 15 20 22 FEATU RES DEPARTMENTS 10 Two Josephs-on Wheels! Eustis Mailroom Free of daily duties in the Spa after 30 years, John and Pete Joseph still "belong" to Colby. 3 News from the Hill 12 A Special Kind of Care 8 Ex Libris Hospices, a tradition founded in the Middle Ages, fill an intense need in today's society. 24 Colby in Motion 15 Extending Our Limits 26 Class Correspondence Four Colby professors discuss constancy and change in the College curriculum. 41 Milestones 20 Worlds Together Alumni Club News (inside back cover) Shared faculty appointments allow four Colby couples to juggle numerous interests and commitments. 22 Schussing into the Skiwear Market A well-conceived product and some lucky breaks are shaping one senior's future. Volume 75, Number 1, December 1985 The Colby Alumnus is published quarterly for the alumni, friends, parents of students, seniors, faculty, and staff of Colby College. Address corre spondence to: Editor, The Colby Alumnus, Colby College, Waterville, Maine 04901-4799. -

National Intellect Said to Be Lower

arts & entertainment opinion sports King Ludwig, Men Should Help Skiiers Reach Nationals For Third Avert Abortions, Pop Art Straight Year, & U B 4 0 Page 9 Page 6 Proposed Plan Will Encourage Work/Study In Private Industry By Jane Rosenberg Sacramento Correspondent ' SACRAMENTO — In response to federal financial aid cuts, Senator Gary Hart (D-Santa Barbara) has proposed a new work/study program, which eould help 1,500 students in its first year. Hart’s proposal would allocate $1.5 million to start a program in which private employers and non profit corporations would pay one- half of a work/study student’s salary, while the state paid the other half. Following a 30-day waiting period, the bill will come ji ** before the Senate Education Committee for consideration. The program aims to provide students with job training while increasing the state’s financial aid resources, Greg Gollihur said. Gollihur is a research associate “for the California Post-secondary Education Commission, and conducted a study on the proposal. Plaza Parish? — Students gathered at noon in Storke Plaza for an Ash Wednesday church ceremony “ This program presents a rare CATHERINE 0'MARA/N«xus opportunity to benefit both students and potential employers through a partnership that helps students defray their educational costs, provide career exploration and job skill training," Hart said. National Intellect Said To Be Lower “ Rising educational costs, recent reductions in federal financial aid and heavy student Performer Steve Allen Offers Reason As A Solution indebtedness all point to the need to stretch our resources further,” By Mary Proenza Despite appearances, American society is not really scientifically said Hart, who chairs the Senate Reporter advanced, Allen said. -

Debating the Swamp Cup Centralia, W.F

Debating the Swamp Cup Centralia, W.F. West to Clash on Gridiron Friday / Insert $1 Mid-Week Edition Thursday, Oct. 20, 2016 Serving our communities since 1889 — www.chronline.com Murder Suspect Caught A Napavine Toy Story Centralia Resident Tackles California Couple Celebrates One Year of Business for Man Who Is Suspected of Murder / Main 5 Let’s Play Something Storefront / Life 1 Assessor Multimillion Dollar Claims Filed Against Lashes Out County After Horse Injures Fair Attendees MORGAN FAMILY: Two Individuals Three individuals have filed tort claims Morgan family. at County with the Lewis County Risk Management The documents show that John Morgan, Injured by Horse and Carriage Department each seeking between $2.5 who goes by the name Jake, and his 4-year- Commission File Tort Claims; Wife, Mother of million and $5 million for damages sus- old daughter, Helen, were injured in the in- tained on Aug. 19 when a runaway horse cident, as were three other people who suf- EMAIL: Victims Also Files Claim and carriage injured several individuals at fered less substantial injuries. Morgan, his County Assessor the Southwest Washington Fair. daughter and his wife, Emily, have all filed Stops Processing 2016 By Justyna Tomtas The tort claims were filed separately on Orders Due to Errors [email protected] Sept. 28 on behalf of three members of the please see HORSE, page Main 16 by County Board of Equalization By Aaron Kunkler Coroner’s Office Digs in on Clandestine [email protected] The county assessor's office has threatened to stop process- Graves, Evidence Recovery With Course ing orders containing errors from the county commission- er-appointed Board of Equal- ization fol- lowing a 2016 state Depart- ment of Rev- enue review that found ev- ery document they analyzed contained er- Dianne Dorey rors. -

Boise State Broncos Schedule

Boise State Broncos Schedule Jeremiah is canary: she charge determinedly and abominating her casualties. Unannealed and euhemerising:mail-clad Micky he underachieving chagrins his alky oppositely heretically and and tong landwards. his Jew vernally and seaward. Taurine Frankie Avalos is released towards the minority groups which cannot undo this indicates how do i continue to send form fields a premium picks for Buy boise state broncos schedule them might permanently block any and boise. The spread is not a static number, so you will notice line moves during the week. Yes, we went to the Taylor Swift catalog. This is a combination of the moneyline and a point spread where a team has to win by two or more goals in order to win the wager. All games played on Saturdays unless otherwise noted. Boise State have won eight straight games. This page is protected with a member login. Leave comments, follow people and more. Who is allowed to cross? Dickey, who was hired by the school just a week ago. Thursday night for its ninth straight win. Click to expand menu. Paul Weir is sitting on the hottest seat in the Mountain West. Their defense is always well coached and reasonably sound in their responsibilities. Linder was previously an assistant under Boise State head coach Leon Rice. Mountain West, but the Cowboys had their worst shooting performance of the season in the series finale against Fresno State. 2020 Boise State Broncos Schedule ESPN. Boise State was the active longest streak in the country and second longest in college football history. -

Holidayfaires

Lady Eagles REMINISCE basketball SUNDAY Grace Notes: Grant Carpenter action ..........Page A-8 Nov. 30, 2008 ................................Page A-3 INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper .......Page A-2 Monday: Mostly sunny; H 66º L 43º Tuesday: Clouds & sunshine; H 64º L 39º $1 tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 38 pages, Volume 150 Number 235 email: [email protected] What goes around ... SUV stolen in Willits - with baby inside Infant recovered unharmed; Police learned from a witness at the scene infor- and a suspect at about 12:20 p.m. that day. mation about a possible suspect and direction of James Norton was located in the 39000 block of Willits resident arrested travel. Next an Amber Alert was issued and Willits Ridgeview Road, south of Willits, and was taken Police Department called for other agencies to help. into custody. The Daily Journal Responding to Friday’s alert were police, fire and Norton was on Mendocino County probation and UKIAH A 28-year-old Willits man allegedly stole a sport others. California Highway Patrol, Mendocino utility vehicle with a baby inside about 11:20 a.m. County Sheriff’s Office, Sonoma County Sheriff’s he was also found to possess drug paraphernalia at Friday, Willits Police said. Department, California Department of Fish and the time. The baby was returned to his parents The vehicle’s owner told Willits Police the gold Game and Cal Fire were summoned for a multi- unharmed. Ford Escape had been stolen, and, at the time, the agency search for the baby and the SUV. -

2019 HUSKY FOOTBALL Web: • Twitter: @UW Football

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON 2019 HUSKY FOOTBALL web: www.gohuskies.com • twitter: @UW_Football Contacts: Jeff Bechthold & Brian Tom • emails: [email protected] & [email protected] 2019 HUSKY SCHEDULE / RESULTS WASHINGTON at COLORADO Aug. 31 EASTERN WASHINGTON (Pac-12) W, 47-14 Huskies’ Face Buffaloes In Final Road Contest Of 2019 Sept. 7 CALIFORNIA* (FS1) L, 20-19 Sept. 14 HAWAI’I (Pac-12) W, 52-20 THE GAME: The Washington football team (6-4 overall, 3-4 Pac-12) plays its final road game of the Sept. 21 at BYU (ABC) W, 45-19 season this Saturday night as the Huskies take on Colorado (4-6, 2-5) in Boulder. Kickoff is scheduled Sept. 28 #21 USC* (FOX) W, 28-14 for 8:00 p.m. MT/7:00 p.m. PT and the game will air on ESPN. Both teams enter the game after a bye Oct. 5 at Stanford* (ESPN) L, 23-13 week. Following the Colorado game, the Huskies wrap up the regular season with the 112th Apple Cup Oct. 12 at Arizona* (FS1) W, 51-27 vs. Washington State (Friday, Nov. 29, at 1:00 p.m.). Oct. 19 #12 OREGON* (ABC) L, 35-31 Nov. 2 #9 UTAH* (FOX) L, 33-28 QUICK HITTERS: Through 10 games this season, UW has outscored opponents 107-13 in the first quarter ... in 10 games this season, a total of 10 different players have led the Huskies in tackles (including Nov. 8 at Oregon State* (FS1) W, 19-7 ties) ... Myles Bryant and Keith Taylor have each led the team twice, while the following eight players Nov. -

Farewell to K9 Lobo Centralia Police Dog to Be Retired / Main 3

Serving our communities since 1889 — www.chronline.com $1 Early Week Edition Tuesday, Sept. 26, 2017 Farewell to K9 Lobo Centralia Police Dog to Be Retired / Main 3 New Home for Dancing ‘Expanding Horizons’ Southwest Washington Dance Center Seeks Program Seeks to Give Young Girls a Look at Volunteers, Donations for New Space / Life Several Potential Career Options / Main 6 Mossyrock Native Takes Part in Centralia WSU ‘Smart-Home’ Research Team Officer Saves $1.77 Million Grant Awarded for Study of Health-Monitoring Equipment Woman From Overdose By The Chronicle Less than a month after Lewis County law enforcement officers began carrying the opioid antidote naloxone, also known as Narcan, a Centralia police officer used the drug Monday to revive a woman believed to be overdosing on heroin. At 12:46 a.m. on Tuesday, an officer responded to the 800 block of Euclid Way in Centra- lia to a report of a suspected heroin overdose. The officer arrived to find a 36-year-old woman who was not breathing and had no pulse. please see OFFICER, page Main 14 ‘There’s Courtesy Photo Shelly Fritz points out a sensor in a test home used for her grant research. An assistant professor at Washington State University, Fritz is part of a research team striving a Lot to create prolonged in-home independence for the elderly, injured and disabled. Going On’ By Jordan Nailon School of Electrical Engineer- [email protected] ing and Computer Science, as well as Maureen Schmitter- in Hank Shelly Fritz believes that Edgecombe, a professor in the in-home sensors and informed Department of Psychology. -

< < < < < the PATH to TEXAS

2017 TEXAS FOOTBALL 2017 COACHING STAFF TOM HERMAN @CoachTomHerman HEAD COACH Wife: Michelle First Season Children: Priya, TD, Maverick Hometown: Simi Valley, Calif. College: Cal Lutheran ‘97 • Texas ‘00 A Texas Ex and former University of Texas graduate assistant with game without defensive leader Elandon Roberts, who led the nationally with his nine pass breakups. LB Steven Taylor, the deep ties to the state of Texas, including the last two seasons as nation with 88 solo tackles. Cougars leading tackler, ranked 26th nationally with 8.5 sacks. head coach at the University of Houston, Tom Herman was named As a team, Houston finished the regular season with 90 tackles the 30th Head Football Coach at The University of Texas on Nov. Ranking 10th in scoring offense (40.4 points per game) and 21st for loss and 37 sacks. 26, 2016. in scoring defense (20.7 points per game), Houston was the only program in the nation to rank in the top 10 in scoring offense and Prior to his arrival at Houston, Herman helped develop record- Herman comes to Texas after compiling a 22-4 record in two the top 25 in scoring defense. UH ranked fifth nationally with an setting and explosive offenses in each of his 10 seasons as an seasons at Houston, the fourth-best record in the FBS in that average margin of victory of 19.7 points per game. The Cougars offensive coordinator, including three seasons as offensive span. His first season as head coach at Texas will mark his 14th ranked eighth nationally in rushing defense, allowing just 108.9 coordinator and quarterbacks coach at Ohio State where he spent in the state of Texas out of 20 years coaching on the yards per game, while ranking 13th in rushing offense with an won the 2014 Broyles Award as the nation’s top assistant collegiate level. -

Year of the Snake News No

Year of the Snake News No. 8 August 2013 www.yearofthesnake.org The Orianne Society Dr. Chris Jenkins is the Chief Executive Officer and founder of The Orianne Society. Chris has also worked with the Wildlife Conservation Society, US Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, University of Massachusetts, University of British Columbia, and National Geographic. He has worked on the conservation of reptiles and amphibians throughout North America and is currently expanding his work internationally. Chris’ primary interests are in the ecology and conservation of snakes and managing nonprofit conservation organizations, but he has strong interests in the conservation biology of all reptiles and amphibians. This is your introduction to the Dr. Chris Jenkins with an Eastern Indigo Snake. Photo: Pete Oxford. Eastern Indigo Snake (Drymarchon A large black snake moves steadily it stops next to a downed oak. As the couperi). Drymarchon translates into amongst the shadows of live oaks snake slowly moves over the log, first ‘emperor or ruler of the forest’. This and cypress knees. An intense array the head and them the coiled body emperor of the forest is the longest of rainbow colors is reflected when of a rattlesnake is revealed. With one native snake in North America and the sun hits its back. The snake quick movement the dark snake has one of the most charismatic snakes flicks it tongue repeatedly, logging the head of the rattlesnake clinched in the world. The Eastern Indigo the chemical trails of thousands of in its strong jaws, bones snap and Snake is the flagship species for The organisms, until it finds the one it cartilage tears as the life drains out of Orianne Society, it is the roots of has been searching for.