Alvin Lucier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voice Phenomenon Electronic

Praised by Morton Feldman, courted by John Cage, bombarded with sound waves by Alvin Lucier: the unique voice of singer and composer Joan La Barbara has brought her adventures on American contemporary music’s wildest frontiers, while her own compositions and shamanistic ‘sound paintings’ place the soprano voice at the outer limits of human experience. By Julian Cowley. Photography by Mark Mahaney Electronic Joan La Barbara has been widely recognised as a so particularly identifiable with me, although they still peerless interpreter of music by major contemporary want to utilise my expertise. That’s OK. I’m willing to composers including Morton Feldman, John Cage, share my vocabulary, but I’m also willing to approach a Earle Brown, Alvin Lucier, Robert Ashley and her new idea and try to bring my knowledge and curiosity husband, Morton Subotnick. And she has developed to that situation, to help the composer realise herself into a genuinely distinctive composer, what she or he wants to do. In return, I’ve learnt translating rigorous explorations in the outer reaches compositional tools by apprenticing, essentially, with of the human voice into dramatic and evocative each of the composers I’ve worked with.” music. In conversation she is strikingly self-assured, Curiosity has played a consistently important role communicating something of the commitment and in La Barbara’s musical life. She was formally trained intensity of vision that have enabled her not only as a classical singer with conventional operatic roles to give definitive voice to the music of others, in view, but at the end of the 1960s her imagination but equally to establish a strong compositional was captured by unorthodox sounds emanating from identity owing no obvious debt to anyone. -

Horizons '83, Meet the Composer, and New Romanticism's New Marketplace

Horizons ’83, Meet the Composer, and New Romanticism’s New Marketplace Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mq/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/musqtl/gdz015/5653100 by guest on 06 December 2019 William Robin The New York Philharmonic was not entirely confident about the pros- pects for a new festival dedicated entirely to contemporary music, to be mounted over two weeks in June 1983. Although more than $80,000 had been budgeted toward advertising and promotion—nearly a tenth of the festival’s total anticipated expenses––advance ticket sales had been slow, perhaps demonstrating that despite recent aesthetic shifts in new music toward styles like minimalism and neo-Romanticism, audiences still felt that contemporary composition was inaccessible, academic, or full of alienating and atonal sounds. On the first night of the festival, dubbed Horizons ’83, the Philharmonic had opened only one of its box office windows at Avery Fisher Hall. But, to everyone’s surprise, a large audi- ence soon appeared, and the queue for same-day tickets quickly stretched out into Lincoln Center’s plaza. As the Philharmonic’s composer-in-residence Jacob Druckman, who curated the Horizons festi- val, later described, “There were 1,500 people lined up around the square and we were frantically telephoning to get somebody to open up other windows.”1 Horizons ’83 was a hit. It would go on to fill Avery Fisher Hall to an average of 70 percent capacity over the festival’s six concerts: A major box office coup for contemporary music, and one com- parable to the orchestra’s ticket sales for standard fare like Beethoven or Mozart. -

Live-Electronic Music

live-Electronic Music GORDON MUMMA This b()oll br.gills (lnd (')uis with (1/1 flnO/wt o/Ihe s/u:CIIlflli01I$, It:clmulogira{ i,m(I1M/;OIn, find oC('(uimwf bold ;lIslJiraliml Iltll/ mm"k Ihe his lory 0/ ciec/muir 111111';(", 8u/ the oIJt:ninf!, mui dosing dlll/J/er.f IIr/! in {art t/l' l)I dilfcl'CIIt ltiJ'ton'es. 0110 Luerd ng looks UfI("/,- 1,'ulIl Ihr vll l/laga poillt of a mnn who J/(u pel'smlfl.lly tui(I/I'sscd lite 1)Inl'ch 0/ t:lcrh'Ollic tccJlIlulogy {mm II lmilll lIellr i/s beg-ilmings; he is (I fl'ndj/l(lnnlly .~{'hooletJ cOml)fJj~l' whQ Iws g/"lulll/llly (lb!Jfll'ued demenls of tlli ~ iedmoiQI!J' ;11(0 1111 a/rc(uiy-/orllleti sCI al COlli· plJSifion(l/ allillldes IInti .rki{l$. Pm' GarrlOll M umma, (m fllr. other IWfI((, dec lroll;c lerllll%gy has fllw/lys hetl! pre.telll, f'/ c objeci of 01/ fl/)sm'uillg rlln'osily (mrl inUre.fI. lu n MmSI; M 1I11111W'S Idslur)l resltllle! ",here [ . IIt:1lillg'S /(.;lIve,( nff, 1',,( lIm;lI i11g Ihe dCTleiojJlm!lIls ill dec/m1/ ;,. IIII/sir br/MI' 19j(), 1101 ~'/J IIIlIrli liS exlell siom Of $/ili em'fier lec1m%gicni p,"uedcnh b111, mOw,-, as (upcclS of lite eCQllol/lic lind soci(ll Irislm)' of the /.!I1riotl, F rom litis vh:wJ}f)il1/ Ite ('on,~i d ".r.f lHU'iQII.f kint/s of [i"t! fu! r/urmrl1lcI' wilh e/cclnmic medifl; sl/)""m;ys L'oilabomlive 1>t:rformrl1lce groU/JS (Illd speril/f "heme,f" of cIIgilli:C'-;lIg: IUltl ex/,/orcs in dt:lllil fill: in/tulmet: 14 Ihe new If'dllllJiolO' 011 pop, 10/1(, rock, nllrl jllu /Ill/SIC llJi inJlnwu:lI/s m'c modified //till Ille recording studio maltel' -

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1990

National Endowment For The Arts Annual Report National Endowment For The Arts 1990 Annual Report National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1990. Respectfully, Jc Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1991 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ............................................................5 The Agency and its Functions .............................................29 . The National Council on the Arts ........................................30 Programs Dance ........................................................................................ 32 Design Arts .............................................................................. 53 Expansion Arts .....................................................................66 ... Folk Arts .................................................................................. 92 Inter-Arts ..................................................................................103. Literature ..............................................................................121 .... Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ..................................137 .. Museum ................................................................................155 .... Music ....................................................................................186 .... 236 ~O~eera-Musicalater ................................................................................ -

THE CLEVELAN ORCHESTRA California Masterwor S

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� ����������������� ����� �������� �������������� ��������� ���������������������� Welcome to the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Orchestra’s performances in the museum California Masterworks – Program 1 in May 2011 were a milestone event and, according to the Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Plain Dealer, among the year’s “high notes” in classical Wednesday evening, May 1, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. music. We are delighted to once again welcome The James Feddeck, conductor Cleveland Orchestra to the Cleveland Museum of Art as this groundbreaking collaboration between two of HENRY COWELL Sinfonietta -

Robert Ashley the Old Man Lives in Concrete

Joan La Barbara – composer / performer / sound artist – explores the human voice as a multi-faceted instrument, expanding traditional boundaries in composition, using a unique vocabulary of experimental and extended vocal techniques – multiphonics, circular singing, ululation and glottal clicks – that have become her “signature sounds.” Awards include a 2008 American Music Center Letter of Distinction, a Guggenheim Fellowship in Music Composition, DAAD Artist-in- Residency in Berlin, seven NEA grants and numerous commissions for concert, theater and radio works. La Barbara has created sound scores for film, video and dance and produced twelve recordings of her own works, including Voice Is the Original Instrument, a double CD of her historical compositions for Lovely Music. 73 Poems, her collaboration with text-artist Kenneth Goldsmith, was included in “The American ROBERT ASHLEY Century Part II: SoundWorks” at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Messa di Voce, an interactive media performance work created in THE OLD MAN LIVES IN CONCRETE collaboration with Jaap Blonk, Golan Levin and Zachary Lieberman, premiered to acclaim at Ars Electronica 2003. La Barbara teaches Music and libretto composition at NYU and is working on a new opera. ROBERT ASHLEY Singers David Moodey has designed for and toured with Molissa Fenley and Dancers since 1986. His design for Fenley’s State of Darkness earned SAM ASHLEY, THOMAS BUCKNER, JACQUELINE HUMBERT, him a Bessie award for lighting design. He has also designed and JOAN LA BARBARA AND ROBERT ASHLEY toured numerous shows for Paul Lazar and Annie-B Parsons and their Electronic orchestra composed by company, Big Dance Theater, and for David Neumann’s feedforward at DTW. -

David Tudor: Live Electronic Music

LMJ14_001- 11/15/04 9:54 AM Page 106 CD COMPANION INTRODUCTION David Tudor: Live Electronic Music The three pieces on the LMJ14 CD trace the development of David Tudor’s solo electronic music during the period from 1970 to 1984. This work has not been well docu- mented. Recordings of these pieces have never before been released. The three pieces each represent a different collaboration: with Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT), with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MCDC) and with Jacqueline Matisse Monnier [1]. The CD’s cover image, Toneburst Map 4, also arises from a collaboration, with the artist Sophia Ogielska. Anima Pepsi (1970) was composed for the pavilion designed by EAT for the 1970 Expo in Osaka, Japan. The piece made extensive use of a processing console consisting of eight identi- cal processors designed and built by Gordon Mumma and a spatialization matrix of 37 loud- speakers. Each processor consisted of a filter, an envelope follower, a ring modulator and a voltage-controlled amplifier. Anima Pepsi used this processing capability to transform a library of recordings of animal and insect sounds together with processed recordings of similar sources. Unlike most of Tudor’s solo electronics, this piece was intended to be performed by other members of the EAT collective, a practical necessity as the piece was to be performed repeatedly as part of the environment of the pavilion for the duration of the exposition. Toneburst (1975) was commissioned to accompany Merce Cunningham’s Sounddance. This recording is from a performance by MCDC, probably at the University of California at Berke- ley, where MCDC appeared fairly regularly. -

PROGRAM NOTES the Expanded Sonic Potential of the Voice

ABOUT THE ARTISTS Joan La Barbara La Barbara is a composer, performer, sound artist and actor renowned for developing a unique vocabulary of experimental and extended vocal techniques (multiphonics, circular singing, ululation and glottal clicks; her “signature sounds”), influencing generations of other composers and singers. Awards, prizes and fellowships include The Foundation for Contemporary Arts John Cage Award (2016); Premio Internazionale Demetrio Stratos; DAAD-Berlin and Civitella Ranieri Artist-in-Residencies; Guggenheim Fellowship in Music Composition; seven National Endowment for the Arts awards (Music Composition, Opera/Music Theater, Inter-Arts, Recording, Solo Recital, Visual Arts), and numerous commissions for multiple voices, chamber ensembles, theatre, orchestra, interactive technology, and soundscores for dance, video and film. Her multi-layered textural compositions were presented at Brisbane Biennial, Festival d’Automne à Paris, Warsaw Autumn, MaerzMusik Berlin and Lincoln Center, among other international venues. She has collaborated with visual artists Matthew Barney, Judy Chicago, Ed Emshwiller, Kenneth Goldsmith, Bruce Nauman, Steina, Woody Vasulka and Lawrence Weiner, and has premiered landmark compositions composed for her, including Morton Feldman’s Three Voices; Morton Subotnick’s chamber opera Jacob’s Room and his Hungers and Intimate Immensity; the title role in Robert Ashley’s opera Now Eleanor’s Idea and his Dust; Philip Glass and Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach; Steve Reich’s Drumming; and John Cage’s Eight Whiskus and Solo for Voice 45 from Song Books. Recordings of her works include ShamanSong (New World), Sound Ellen Rietbrock Paintings and her seminal works from Voice is the Original Instrument (1970, Lovely Music). In addition to her internationally acclaimed discs of Feldman and Cage, she has recorded for A&M Horizon, Centaur, Deutsche Grammophon, Nonesuch, Mode, Music & Arts, MusicMasters, Musical Heritage, Newport Classic, Sony, Virgin, Voyager and Wergo. -

Alvin Lucier's

CHAMBERS This page intentionally left blank CHAMBERS Scores by ALVIN LUCIER Interviews with the composer by DOUGLAS SIMON Wesleyan University Press Middletown, Connecticut Scores copyright © 1980 by Alvin Lucier Interviews copyright © 1980 by Alvin Lucier and Douglas Simon Several of these scores and interviews have appeared in similar or different form in Arts in Society; Big Deal; The Painted Bride Quar- terly; Parachute; Pieces 3; The Something Else Yearbook; Source Magazine; and Individuals: Post-Movement Art in America, edited by Alan Sondheim (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1977). Typography by Jill Kroesen The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of a Wesleyan University Project Grant. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Lucier, Alvin. [Works. Selections] Chambers. Concrete music. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Concrete music. 2. Chance compositions. 3. Lucier, Alvin. 4. Composers—United States- Interviews. I. Simon, Douglas, 1947- II. Title. M1470.L72S5 789.9'8 79-24870 ISBN 0-8195-5042-6 Distributed by Columbia University Press 136 South Broadway, Irvington, N.Y. Printed in the United States of America First edition For Ellen Parry and Wendy Stokes This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS Preface ix 1. Chambers 1 2. Vespers 15 3. "I Am Sitting in a Room" 29 4. (Hartford) Memory Space 41 5. Quasimodo the Great Lover 53 6. Music for Solo Performer 67 7. The Duke of York 79 8. The Queen of the South and Tyndall Orchestrations 93 9. Gentle Fire 109 10. Still and Moving Lines of Silence in Families of Hyperbolas 127 11. Outlines and Bird and Person Dyning 145 12. -

Computer Music Experiences, 1961-1964 James Tenney I. Introduction I Arrived at the Bell Telephone Laboratories in September

Computer Music Experiences, 1961-1964 James Tenney I. Introduction I arrived at the Bell Telephone Laboratories in September, 1961, with the following musical and intellectual baggage: 1. numerous instrumental compositions reflecting the influence of Webern and Varèse; 2. two tape-pieces, produced in the Electronic Music Laboratory at the University of Illinois — both employing familiar, “concrete” sounds, modified in various ways; 3. a long paper (“Meta+Hodos, A Phenomenology of 20th Century Music and an Approach to the Study of Form,” June, 1961), in which a descriptive terminology and certain structural principles were developed, borrowing heavily from Gestalt psychology. The central point of the paper involves the clang, or primary aural Gestalt, and basic laws of perceptual organization of clangs, clang-elements, and sequences (a higher order Gestalt unit consisting of several clangs); 4. a dissatisfaction with all purely synthetic electronic music that I had heard up to that time, particularly with respect to timbre; 2 5. ideas stemming from my studies of acoustics, electronics and — especially — information theory, begun in Lejaren Hiller’s classes at the University of Illinois; and finally 6. a growing interest in the work and ideas of John Cage. I leave in March, 1964, with: 1. six tape compositions of computer-generated sounds — of which all but the first were also composed by means of the computer, and several instrumental pieces whose composition involved the computer in one way or another; 2. a far better understanding of the physical basis of timbre, and a sense of having achieved a significant extension of the range of timbres possible by synthetic means; 3. -

Academiccatalog 2017.Pdf

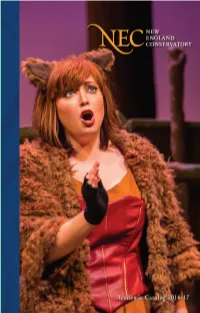

New England Conservatory Founded 1867 290 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 necmusic.edu (617) 585-1100 Office of Admissions (617) 585-1101 Office of the President (617) 585-1200 Office of the Provost (617) 585-1305 Office of Student Services (617) 585-1310 Office of Financial Aid (617) 585-1110 Business Office (617) 585-1220 Fax (617) 262-0500 New England Conservatory is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. New England Conservatory does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, age, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, physical or mental disability, genetic make-up, or veteran status in the administration of its educational policies, admission policies, employment policies, scholarship and loan programs or other Conservatory-sponsored activities. For more information, see the Policy Sections found in the NEC Student Handbook and Employee Handbook. Edited by Suzanne Hegland, June 2016. #e information herein is subject to change and amendment without notice. Table of Contents 2-3 College Administrative Personnel 4-9 College Faculty 10-11 Academic Calendar 13-57 Academic Regulations and Information 59-61 Health Services and Residence Hall Information 63-69 Financial Information 71-85 Undergraduate Programs of Study Bachelor of Music Undergraduate Diploma Undergraduate Minors (Bachelor of Music) 87 Music-in-Education Concentration 89-105 Graduate Programs of Study Master of Music Vocal Pedagogy Concentration Graduate Diploma Professional String Quartet Training Program Professional