ED080519.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paris 2018 Gay Games 10 Page 6

No. 551 • April 28, 2016 • outwordmagazine.com Paris 2018 Gay Games 10 page 6 Dying to Live LGBT Sacramento Valley Mr. Bolt Leather CGNIE Crowns a New Veterans Stand Down 2016 Ray Sherwin Emperor and Empress page 11 page 14 page 15 page 20 COLOR COLOR Find Your Escape! 2016 Subaru Outback Remembering Gerald Louis “Gerry” Arredondo Remembering Daved Girard Gerald Louis “Gerry” Arredondo, age 62, My Beautiful Daved is gone and I am so Outword passed away at Kaiser Hospital, Roseville, on heart broken. He was my partner of six Sunday, April 10, 2016. wonderful years and my one true LOVE. I Born on December 12, 1953, in San Jose, would like to share with you a poem that he Staff he graduated from Mount Pleasant High wrote, so that you might know him better. TJ Bruce PUBLISHER School in San Jose and worked and lived Fred Palmer several years in San Jose before settling in Roseville, 13 years ago. ART DIRECTOR/PRODUCTION He worked at the Lincoln Station of the Ron Tackitt United States Postal Service as a Rural GRAPHIC DESIGN Carrier, and was a member of the Ron Tackitt Sacramento Gay Men’s Chorus. Marc Hébert Survivors include his partner, Michael Harrison; and his daughter, Nicole Terry and EDITOR her husband, Leslie and children, Hannah Charles Peer [email protected] and Madison; and his son, Niklaus Arredondo and his companion, Maria, and ARTS EDITOR children, Soyla and Selma; and his parents, Chris Narloch Jay and Mary Arredondo, and his sister, Betty Gerald Louis “Gerry” Arredondo Arredondo. In addition, he has several A funeral service will be held Tuesday, SALES Fred Palmer Uncles, Aunts and Cousins; and a wealth of April 19, at 1:30 p.m. -

New Fallout Danger Revealed

\ i , HIGH TI DE HIGH TIDE I 8/27/63 8/27/63 "I 3 6 AT 0812 2.2 AT 0227 > 3.9 AT 2106 :lite HOURGLASS 2.0 AT 1432 1-----------------------------------------------------------------I ______________________ _ VOL 4 NO. 1508 KWAJALEIN, MARSHALL ISLANDS MONDAY, 26 AUGUST 1963 HOPE GROWS FOR TWO MINERS NEW FALLOUT DIM FOR THIRD DANGER REVEALED SHEPPTON, PENNSYLVANIA, (UPI )--THE FINAL STAGE OF DRILL WASHINGTON, (UPI )--NUCLEAR SCIENTISTS TESTIFYING BEFORE liNG TO REACH TWO MINERS TRAPPED 308 FEET UNDERGROUND FOR CONGRESS HAVE TURNED A SPOTLIGHT ON A NEWLY RECOGNIZED I 13 DAYS CONTINUED TONIGHT WITH PAINSTAKING DELIBERATION. DANGER OF RADIO-ACTIVE FALLOUT TO WHICH SEVERAL THOUSAND RESCUERS HOPED TO BRING THEM TO THE SURFACE SOMETIME CHILDREN APPARENTLY HAVE ALREADY BEEN EXPOSED. TOMORROW. THE EXPOSURES, ACCORDING TO THE SCIENTISTS, OCCURRED AT , A 17 1/2-INCH DRILL WENT INTO OPERATION AT 2:26 A.M., INTERVALS OVER THE PAST 12 YEARS WHEN RADIO-ACTIVE IODINE I EDT, STARTING AT THE 38-FOOT LEVEL, TO WIDEN A 12-INCH WAS DEPOSITED ON PASTURE LAND IN "HOT SPOTS" AFTER NEVADA OPENING ALREADY DUG TO THE CHAMBER WHERE HENRY THRONE, 28, NUCLEAR TESTS. IT WAS CONSUMED BY THE CHILDREN IN FRESH i AND DAVID FELLIN, 5 8 , HAVE BEEN ENTOMBED SINCE AUGUST 13· MI LK. THE REAMING OPERATION WAS PROCEEDING AT THE RATE OF ONLY THE SCIENTISTS' CALCULATIONS, SUBMITTED LAST WEEK, IN A fEW fEET PER HOUR, AND BY 8:42 P.M. THE DRILL HAD DICATED THE EXPOSURES WERE AT A LEVEL WHICH WOULD PRO I PENETRATED 85 FEET INTO THE GROUND. -

European Masterworks in Memoriam SCSO Cellist & Friend, Judy Waegell

Sacramento Choral Society & Orchestra Donald Kendrick, Music Director Saturday, March 8 ~ 8 p.m. Pre-concert talk ~ 7 p.m. Sacramento Community Center Theater European Masterworks In Memoriam SCSO Cellist & Friend, Judy Waegell Stabat Mater 1907 Charles Villiers Stanford 1852 –1924 Marina Boudart Harris, Soprano Malin Fritz, Alto Mathew Edwardsen, Tenor Eugene Villanueva, Baritone 1. Prelude 2. Stabat Mater dolorosa 3. Intermezzo 4. Eja Mater 5. Finale – Virgo virginum praeclara Intermission Symphony No. 2 Lobgesang 1840 Felix Mendelssohn 1809–1847 Marina Boudart Harris, Soprano Carrie Hennessey, Soprano Mathew Edwardsen, Tenor 1. Sinfonia 2. Alles was Odem hat lobe den Herrn Chorus, Soprano 3. Saget es Tenor 4. Sagt es, die ihr erlöst seid Chorus 5. Ich harrete des Herrn Soprano, Mezzo, Chorus 6. Strick des Todes hatten uns umfangen Tenor, Soprano 7. Die Nacht ist vergangen Chorus 8. Nun danket alle Gott Chorus 9. Drum sing’ ich mit meinem Liede Tenor, Soprano 10. Ihr Völker! Bringet her dem Herrn Ehre und Macht Chorus SINCE ITS ESTABLISHMENT IN 1996, the Sacramento Choral Society and Orchestra (SCSO), conducted by Donald Kendrick, has grown to become one of the largest symphonic choruses in the United States. Members of this auditioned, volunteer, professional-caliber chorus, hailing from six different Northern California Counties, have formed a unique arts partnership with their own professional symphony orchestra. The Sacramento Choral Society is a non-profit organization and is governed by a Board of Directors responsible for the management of the Corporation. An Advisory Board and a Chorus Executive elected from within the ensemble also assist the Society in meeting its goals. -

Sacramento Choral Society & Orchestra

SACRAMENTO CHORAL SOCIETY & ORCHESTRA Donald Kendrick, Music Director Saturday, May 14, 2016 ~ 8 p.m. Pre-concert talk ~ 7 p.m. Sacramento Community Center Theater EUROPEAN MASTERWORKS IN MEMORY of Stan Lunetta An Oxford Elegy Vaughan Williams Narrator: Phillip Ryder Psalm 149 Antonín Dvořák INTERMISSION Harmoniemesse Franz Joseph Haydn Sara Duchnovnay, Soprano Malin Fritz, Mezzo Soprano Christopher Bengochea, Tenor Matt Boehler, Bass I. Kyrie II. Gloria III. Credo IV. Sanctus V. Benedictus VI. Agnus Dei SINCE ItS EStABlISHmENT In 1996, the Sacramento Choral Society and Orchestra (SCSO), conducted by Donald Kendrick, has grown to become one of the largest symphonic choruses in the United States. Members of this auditioned, volunteer, professional-caliber chorus, hailing from six different Northern California counties, have formed a unique arts partnership with their own professional symphony orchestra. The Sacramento Choral Society is a non-profit organization and is governed by a Board of Directors responsible for the management of the Corporation. An Advisory Board and a Chorus Executive elected from within the ensemble also assist the SCSO in meeting its goals. BoarD OF DIrEctOrS conductor/Artistic Director–Donald Kendrick President–James McCormick Secretary–Charlene Black treasurer–Maria Stefanou marketing & Pr Director–Jeannie Brown Development & Strategic Planning –Douglas Wagemann chorus Operations –Catherine Mesenbrink At-large Director (SCSO Chorus) –Tery Baldwin At-large Director–George Cvek At-large Director–Rani Pettis Advisory -

Scso 2 Min Video

Sacramento Choral Society & Orchestra The Sacramento Choral Society & Orchestra (SCSO) is an auditioned, volunteer chorus of 150-180 voices committed to the performance, education, and appreciation of a wide range of choral orchestral music for the Greater Sacramento, California Region. Their mission is to provide large-scale choral works at attractive family prices. The SCSO, previously the Sacramento Symphony Chorus, was formed as a California 501 c (3) nonprofit organization in 1996 when the Sacramento Symphony disbanded. The group is known as the Sacramento Choral Society (SCS) when not performing with orchestra. The SCSO performs at the Sacramento Community Center Theater and Memorial Auditorium in Sacramento and Mondavi Center for the Performing Arts at the University of California at Davis. In 2009 the SCS initiated a Sacramento Stained Glass Series at Sacramento’s landmark Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, a venue which allows performance of glorious smaller-scale repertoire in the more intimate acoustics of a church. Other Stained Glass venues include Fremont Presbyterian Church, featuring its new Reuter pipe organ and its renovated sanctuary. The SCSO’s repertoire embraces the great choral works from the Renaissance to contemporary composers. The organization takes great pride in regularly inviting world- class soloists to join their large team onstage. An annual Home for the Holidays concert series is a highly anticipated kick-off to the Christmas season. The SCSO has performed a number of pops programs including music of Rodgers & Hammerstein, Lerner & Loewe, and Cole Porter. The SCSO’s programs are eclectic, global, and thrilling and each performance is world class. The SCSO was founded by its artistic director Dr. -

Carmina Burana in Memory of Tevye Ditter 1974–2014 Friend, Singer, Actor, Dancer, Amazing Human Being

Sacramento Choral Society & Orchestra Donald Kendrick, Music Director Saturday, May 17 ~ 8 p.m. Pre-concert talk ~ 7 p.m. Sacramento Community Center Theater Special Guests: Sacramento State University Chorus Sacramento Children’s Chorus Lynn Stevens, Director Carmina Burana In Memory of Tevye Ditter 1974–2014 Friend, Singer, Actor, Dancer, Amazing Human Being Schicksalslied (The Song of Fate) Johannes Brahms Angels’ Voices John Burge Sacramento Children’s Chorus Toward The Unknown Region Ralph Vaughan Williams Intermission Carmina Burana Carl Orff Nikki Einfeld, Soprano Kirill Dushechkin, Tenor Dan Kempson, Baritone Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi (Fortune, Empress of the World) I. Primo vere (In Stringtime) Uf dem anger (On the Lawn) II. In Taberna (In the Tavern) III. Cour d’amours (The Court of Love) Blanziflor et Helena (Blanchefleur and Helen) Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi (Fortune, Empress of the World) SINCE ITS ESTABLISHMENT IN 1996, the Sacramento Choral Society and Orchestra (SCSO), conducted by Donald Kendrick, has grown to become one of the largest symphonic choruses in the United States. Members of this auditioned, volunteer, professional-caliber chorus, hailing from six different Northern California Counties, have formed a unique arts partnership with their own professional symphony orchestra. The Sacramento Choral Society is a non-profit organization and is governed by a Board of Directors responsible for the management of the Corporation. An Advisory Board and a Chorus Executive elected from within the ensemble also assist the Society -

Sacramento Choral Society & Orchestra

SEASON 23 SACRAMENTO CHORAL SOCIETY & ORCHESTRA DONALD KENDRICK, MUSIC DIRECTOR 2018 2019 Oct 20 Stained Glass | Fremont Presbyterian Community Center Theater Dec 8 Wells Fargo Home for the Holidays Mar 23 European Masterworks | Brahms Requiem May 14 Light and Fire Sacramento Choral Society & Orchestra Donald Kendrick, Music Director Ryan Enright, Organist Saturday, October 20, 2018 ~ 8 p.m. Fremont Presbyterian Church, Sacramento STAINED GLASS SONGS OF THE SPIRIT In Memory of Billy Halloran 1999–2018 Patricia Westley, Soprano Julie Miller, Mezzo Michael Dailey, Tenor Shawn Spiess, Bass Berliner Messe 1990 Arvo Pärt 1935 – Kyrie Gloria Erster Alleluiavers (First Alleluia) Zweiter Alleluiavers (Second Alleluia) Veni Sancte Spiritus Credo Sanctus Agnus Dei Litaniae de venerabili altaris Sacramento, K125 Mozart 1756 – 1791 1. Kyrie – Chorus 2. Panis Vivus – Soprano Solo 3. Verbum Caro Factum – Chorus, SATB Solo 4. Tremendum ac vivificum –Chorus 5. Panis omnipotentia – Tenor Solo 6. Viaticum – Soprano Solo and Chorus 7. Pignus futurae gloriae – Chorus 8. Agnus Dei – Soprano Solo and Chorus Laudes Organi 1966 Zoltán Kodály 1882 – 1967 We invite you to join us at our SCSO reception immediately following tonight’s performance. MISSION The Sacramento Choral Society and Orchestra (SCSO), a California educational 501 c (3) non-profit organization established in 1996, is an auditioned, volunteer chorus with a professional orchestra committed to the performance, education, and appreciation of a wide range of choral orchestral music for the Greater Sacramento Region. Since its establishment, the SCSO, conducted by Donald Kendrick, has grown to become one of the largest symphonic choruses in the United States. Members of this auditioned, volunteer, professional-caliber chorus, hailing from six different Northern California counties, have formed a unique arts partnership with their own professional symphony orchestra. -

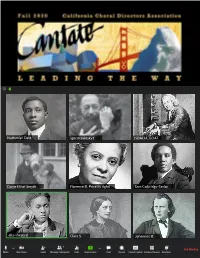

Cantate (Fall 2020)

Nathaniel_Dett igorstravinsky1 JSBACH_GOAT Dame Ethel Smyth Florence B. Price (is right) Sam Coleridge-Taylor ella-shepard Clara S. Johannes B. At the CSU Fullerton School of Music, We Believe … …that people learn and perform best in a safe and positive environment. …in student-centered teaching and learning. …that developing musicianship is key to your future success. …that Everything we do, we do Together. …that the quality of your musical training really matters. …in the power of music to change lives for the better. …that professionalism is a teachable skill. …that great conductors and singers must also be great teachers. …that how you do anything affects how you do everything. …in Reaching Higher to help you achieve your goals. …that Everything relates to Everything. …that together we are stronger. …that you will teach the way that you were taught. …that where you have been is much less important than where you are going. WHAT we do is important. WHY we do it, is for YOU! music.fullerton.edu 2 • CANTATE • VOL. 33, NO. 1 • FALL 2020 CALIFORNIA CHORAL DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION IN THIS ISSUE 5 | LEARNING AND GROWING FROM THE PRESIDENT’S PEN · BY JEFFREY BENSON 6 | “SHOW THEM THE LOVE” LETTER FROM THE EDITOR · BY ELIZA RUBENSTEIN AND BRANDI BIRDSONG 9 | COCOONING THE COMPOSER’S VOICE · BY DALE TRUMBORE 10 | ALL-STATE HONOR CHOIRS BY MOLLY PETERS 12 | 2020 HOWARD SWAN AWARD WINNERS 16 | SEEN & HEARD 19 | NOW WHAT? CROWD-SOURCED RESOURCES FOR REMOTE LEARNING FROM CCDA MEMBERS 47 | GEORGE HEUSSENSTAMM COMPOSITION CONTEST WINNER BY DAVID MONTOYA 66 | NEWS AND NOTES HAPPENINGS FROM AROUND THE STATE 69 | VISION FOR THE FUTURE SCHOLARSHIP FUND DONORS 70 | CCDA DIRECTORY our summer home at ECCO is quiet this year, but CCDA members are staying connected as we navigate the pandemic and look ahead to gathering in person in 2021! LEADING THE WAY CANTATE • VOL. -

Sacramento Choral Society &Orchestra Donald Kendrick | Music Director

SACRAMENTO CHORAL SOCIETY & ORCHESTRA DONALD KENDRICK | MUSIC DIRECTOR 2014 /15 SEASON 19 BRINGING MUSIC AND COMMUNITY TO LIFE OCT 25 STAINED GLASS | FREMONT PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH DEC 13 WELLS FARgo HoME FOR THE HoLIDAYS | MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM MAR 14 EURopEAN MASTERWORKS | CoMMUNITY CENTER THEATER MAY 9 SONgs of ETERNITY | CoMMUNITY CENTER THEATER Timeless music all the time. 91.7 FM Sonora/Groveland 88.9 FM Sacramento 88.7 FM Sutter/Yuba City Sacramento Choral Society & Orchestra Donald Kendrick, Music Director Saturday, October 25, 2014 ~ 8 p.m. Fremont Presbyterian Church, Sacramento Stained Glass Concert Ryan Enright, Organist SCSO Festival Brass: John Leggett, Dan McCrossen, Chuck Bond Oboe: Kathy Conner, Cindy Behmer Timpani: Matt Darling Prélude et Fugue sur le nom d’Alain, Op. 7 Maurice Duruflé 1902–1986 Ave Regina Caelorum Gregorian Chant Ave Regina Caelorum Orlando di Lasso 1530–1594 Adoro Te Devote Gregorian Chant Adoro Te Devote Stephen Caracciolo 1962– Dettingen Te Deum George Frederic Handel 1685–1759 Karlie Saenz, Mezzo Soprano John Martin, Baritone 1. We Praise Thee, O God 2. All The Earth 3. To Thee Cherubin 4. The Glorious Company 5. Thine Honourable, True, and Only Son 6. Thou Art The King of Glory 7. When Thou Tookest Upon Thee 8. When Thou Hadst Overcome 9. Thou Didst Open 10. Thou Sittest at the Right Hand of God 11. Symphony 12. We Therefore Pray Thee 13. Make Them To Be Numbered 14. Day By Day 15. And We Worship Thy Name 16. Vouchsafe, O Lord 17. O Lord, In Thee Have I Trusted 2014–2015 SACraMENTO CHOraL SOCIETY & ORCHESTra 1 SINCE ITS ESTABLISHMENT IN 1996, the Sacramento Choral Society and Orchestra (SCSO), conducted by Donald Kendrick, has grown to become one of the largest symphonic choruses in the United States. -

European Masterworks in Memoriam Paul Salamunovich Magnificat Cecilia Mcdowall Nikki Einfeld, Soprano Marina Boudart Harris, Soprano 1

Sacramento Choral Society & Orchestra Donald Kendrick, Music Director Saturday, March 14, 2015 ~ 8 p.m. Sacramento Community Center Theater European Masterworks In Memoriam Paul Salamunovich Magnificat Cecilia McDowall Nikki Einfeld, Soprano Marina Boudart Harris, Soprano 1. Magnificat Chorus 2. Ecce enim ex hoc beatam Soprano 3. Quia fecit mihi magna Chorus 4. Et misericordia Mezzo 5. Fecit potentiam Soprano Duet 6. Deposuit potentes Chorus Intermission Great Mass in C Minor, kv 427 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Nikki Einfeld, Soprano Marina Boudart Harris, Soprano Ross Hauck, Tenor Daniel Yoder, Bass Kyrie Chorus/Soprano I Gloria Gloria Chorus Laudamus Te Soprano II Gratias agimus tibi Chorus Domine Deus Soprano Duet Qui tollis peccata mundi Chorus Quoniam to solus Sanctus Soprano I/Soprano II/Tenor Jesu Christe Chorus Cum Sancto Spiritu Chorus Credo Credo in unum deum Chorus Et incarnatus est Soprano I Sanctus Sanctus/Osanna in excelsis Chorus Benedictus Tutti/Chorus 2014–2015 SACraMENTO CHOraL SOCIETY & ORCHESTra 1 SINCE ITS ESTABLISHMENT IN 1996, the Sacramento Choral Society and Orchestra (SCSO), conducted by Donald Kendrick, has grown to become one of the largest symphonic choruses in the United States. Members of this auditioned, volunteer, professional-caliber chorus, hailing from six different Northern California counties, have formed a unique arts partnership with their own professional symphony orchestra. The Sacramento Choral Society is a non-profit organization and is governed by a Board of Directors responsible for the management -

A Crosby Christmas™ Hosted by Jim Raposa Licensed for Unlimited Local Broadcast Between: 11/1/2020 - 12/25/2020 at Midnight Local Time

A Crosby Christmas™ Hosted by Jim Raposa Licensed for unlimited local broadcast between: 11/1/2020 - 12/25/2020 at Midnight local time. SEGMENT ONE/Running time: 19:06 In cue: (singing) “When the blue of the night meets…” MUSIC: Opening theme Adeste Fideles – Bing Crosby (1946 radio broadcast) MEDLEY: Deck the Halls/Away in a Manger/O Little Town of Bethlehem/ The First Noel – Bing Crosby (1951 radio broadcast) Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas – Bing Crosby (1962) Mele Kalikimaka – Bing Crosby & the Andrews Sisters (1950) Jingle Bells – Bing Crosby & the Andrews Sisters (1950) FEATURE: Interviews – Bing Crosby and Maxene Andrews Out cue: “…radio exchange, this is A Crosby Christmas.” (Harp run sting) __________________________________________________________________ SEGMENT TWO/Running time: 15:54 In cue: “Welcome back to a Crosby…” MUSIC: The Christmas Song – Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra (1957 telecast) Song parody medley – Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra (1945 radio broadcast excerpt) We Wish You the Merriest! – Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra (1964) Snow – Bing Crosby; Rosemary Clooney; Danny Kaye and Gloria Wood (1954) Here Comes Santa Claus – Bing Crosby and Peggy Lee (1949 radio broadcast) Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer – Bing Crosby and Ella Fitzgerald (1950 broadcast) FEATURE: Interviews – Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra and Rosemary Clooney Out cue: “…please stay with us.” (music sting) __________________________________________________________________ SEGMENT THREE/Running time: 22:30 In cue: “A Crosby and Friends Christmas continues…” MUSIC: Do You Hear What I Hear? – Bing Crosby (1963) On the Very First Day of the Year – Bing Crosby (1977) Little Drummer Boy/Peace on Earth – Bing Crosby/David Bowie (2019) Crosby Christmas Medley – Bing, Gary, Lindsay, Phillip & Dennis Crosby (1950) Around the Corner – Bing Crosby (1977 narration) White Christmas – Bing Crosby (1952 radio broadcast) FEATURE: Interview – Bing Crosby. -

Jimmy Van Heusen Papers PASC-M.0127

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5s20204k No online items Finding Aid for the Jimmy Van Heusen Papers PASC-M.0127 Finding aid prepared by Kevin C. Miller of the Center for Primary Research and Training Plus, UCLA Special Collections staff, 2009; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2021 January 4. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Jimmy Van PASC-M.0127 1 Heusen Papers PASC-M.0127 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Jimmy Van Heusen papers Creator: Van Heusen, Jimmy 1913-1990 Identifier/Call Number: PASC-M.0127 Physical Description: 83 Linear Feet(166 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1853-1994 Date (bulk): 1939-1972 Abstract: Collection consists of American song composer Jimmy Van Heusen's papers and materials, both business and personal. Items include an extensive collection of unpublished music manuscripts and song lyrics, published sheet music, correspondence, personal papers, and business documents. Many materials relate to his interactions with Johnny Burke, Sammy Cahn, Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, and others, and to his publishing companies Burke & Van Heusen, Inc. and Van Heusen Music Corporation. Also includes sound and audiovisual materials, including his personal LP collection, unpublished home recordings, and home movies. Photographic material includes both press and personal prints, some negatives, and color slides. Other items include performance scripts, altered lyrics, biographic materials, professionally assembled scrapbooks, and other published materials from his personal collection.