Houston Parks—Where Memories Are Made

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hermann Park Japanese Garden Day Honors 40 Years of Friendship

Estella Espinosa Houston Parks and Recreation Department 2999 South Wayside Houston, TX 77023 Office: (832) 395-7022 Cell: (832) 465-4782 Alisa Tobin Information & Cultural Affairs Consulate-General of Japan 909 Fannin, Suite 3000 Houston, Texas 77010 Office: (713) 287-3745 Release Date: 06/15/2012 (REVISED) Hermann Park Japanese Garden Day Honors 40 Years of Friendship Between COH & Chiba City, Japan 20 Cherry Blossom Trees to Be Planted As Part of Centennial Celebration of Tree Gift to US from Japan Mayor Annise Parker will recognize Mr. Kunio Minami, local community groups, & many individuals for their dedication & work to the maintenance of one of Houston's most enduring symbols of friendship, the Japanese Garden at Hermann Park. In recognition of this dedication & in honor of the friendship between the City of Houston & its sister city, Chiba City, Japan, Tuesday, June 19 will be proclaimed Hermann Park Japanese Garden Day in the City of Houston. "For the past two decades, the Japanese Garden has served as a visible symbol of the friendship between Houston & Chiba City," said Houston Mayor Annise Parker. "We are truly honored to acknowledge the lasting friendship this garden personifies, with its beautiful pathways, gardens, & trees." In 1912, the People of Japan gave to the People of the United States 3,000 flowering cherry trees as a gift of friendship. In commemoration of this centennial & in recognition of the 40th anniversary of the Houston-Chiba City sister city relationship, 20 new cherry trees will be planted in the Japanese Garden in Hermann Park in October of this year. -

Motorcycle Parking

C am b rid ge Memorial S Hermann t Medical Plaza MOTORCYCLE PARKING Motorcycle Parking 59 Memorial Hermann – HERMANN PARK TO DOWNTOWN TMC ay 288 Children’s r W go HOUSTON Memorial re G Hermann c HOUSTON ZOO a Hospital M Prairie View N A&M University Way RICE egor Gr Ros ac UNIVERSITY The Methodist UTHealth s M S MOTORCYCLE S Hospital Outpatient te PARKING Medical rl CAMPUS Center MOTORCYCLE in p School PARKING g o Av Garage 4 o Garage 3 e L West t b S u C J HAM– a am Pavilion o n T d St h e en TO LELAND n St n n Fr TMC ll D i i Library r a n e u n ema C ANDERSON M a E Smith F MOTORCYCLE n Tower PARKING Bl CAMPUS vd Garage 7 (see inset) Rice BRC Building Scurlock Tower Mary Gibbs Ben Taub Jones Hall Baylor College General of Medicine Hospital Houston Wilk e Methodist i v ns St A C a Hospital g m M in y o MOTORCYCLE b a John P. McGovern u PARKING r MOTORCYCLE r TIRR em i W Baylor PARKING TMHRI s l d TMC Commons u F r nd St Memorial g o Clinic Garage 6 r e g Garage 1 Texas Hermann a re The O’Quinn m S G Children’s a t ac Medical Tower Mitchell NRI L M at St. Luke’s Building Texas Children’s (BSRB) d Main Street Lot e Bellows Dr v l Texas v D B A ix Children’s Richard E. -

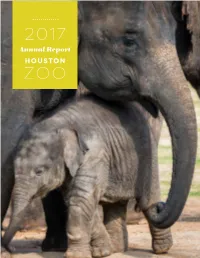

2017 Annual Report HOUSTON ZOO Our Houston Zoo Is Vibrant, Growing, and Touching Hearts and Minds to Make a Difference for People and Animals Alike

2017 Annual Report HOUSTON ZOO Our Houston Zoo is vibrant, growing, and touching hearts and minds to make a difference for people and animals alike. In 2017, more than 2.4 million guests walked through our gates, many of them free of charge or at greatly reduced admission. Despite extreme weather events like Hurricane Harvey impacting our attendance results, the Houston Zoo remains the second- most visited zoo in the United States among those that charge admission. It’s clear that this urban oasis in the heart of our city remains top-of-mind for Houstonians and out-of-town visitors looking to share new memories while connecting with nature. Having a dedicated base of support from our community helped us achieve laudable success saving wildlife locally and around the world in 2017. We released more than 900,000 Houston toad eggs into the wild to ensure the survival of these native Texas amphibians. Our veterinary team provided medical care for more than 80 injured or stranded sea turtles. We saw tangible results from our long-term support of mountain gorillas in Africa and elephant populations in Borneo. And a strong culture of conservation is evident throughout our organization as team members from many different departments participated in conservation action opportunities. In 2017, we made significant facility upgrades around the Zoo for guests and animals. We opened Explore the Wild, a nature play area specially created to inspire children to engage with the natural world around them. An expansion of the McNair Asian Elephant Habitat added a new barn, swimming pool, and spacious exhibit yard for our bull elephants. -

Where's the Revolution?

[Where’s the] 32 REVOLUTION The CHANGING LANDSCAPE of Free Speech in Houston. FALL2009.cite CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: Menil Collection north lawn; strip center on Memorial Drive; “Camp Casey” outside Crawford, Texas; and the George R. Brown Convention Center. 1984, Cite published an essay by Phillip Lopate en- titled “Pursuing the Unicorn: Public Space in Hous- ton.” Lopate lamented: “For a city its size, Houston has an almost sensational lack of convivial public space. I mean places where people congregate on their own for the sheer pleasure of being part of a INmass, such as watching the parade of humanity, celebrating festivals, cruis- ing for love, showing o! new clothing, meeting appointments ‘under the old clock,’ bumping into acquaintances, discussing the latest political scandals, and experiencing pride as city dwellers.” Twenty-seven years later, the lament can end. After the open- the dawn of a global day of opposition. In London between ing of Discovery Green, the Lee and Joe Jamail Skatepark, 75,000 and two million were already protesting. For Rome, and the Lake Plaza at Hermann Park, the city seems an alto- the estimates ranged from 650,000 to three million. Between gether different place. The skyline itself feels warmer and 300,000 and a million people were gathering in New York more humane when foregrounded by throngs of laughing City, and 50,000 people would descend upon Los Angeles children of all stripes. The strenuous civic activity of count- later in the day. less boosters and offi cials to make these fabulous public Just after noon, when the protest in Houston was sched- spaces is to be praised. -

Animal Care Internship Descriptions & Requirements

Animal Care Internship Descriptions & Requirements Table of Contents AMBASSADOR ANIMAL INTERNSHIP ............................................................................................................. 2 AQUARIUM INTERNSHIP ................................................................................................................................. 3 BIRDS INTERNSHIP ......................................................................................................................................... 4 CARNIVORE INTERNSHIP ............................................................................................................................... 5 CHILDREN’S ZOO INTERNSHIP ...................................................................................................................... 6 ELEPHANTS INTERNSHIP ............................................................................................................................... 7 HERPETOLOGY INTERNSHIP ......................................................................................................................... 8 HOOF STOCK INTERNSHIP ............................................................................................................................ 9 HOUSTON TOADS HUSBANDRY INTERNSHIP ............................................................................................ 10 INVERTEBRATE INTERNSHIP ....................................................................................................................... 11 NATURAL ENCOUNTERS -

Final Report September 4, 2015

Final Report September 4, 2015 planhouston.org Houston: Opportunity. Diversity. Community. Home. Introduction Houston is a great city. From its winding greenways, to its thriving arts and cultural scene, to its bold entrepreneurialism, Houston is a city of opportunity. Houston is also renowned for its welcoming culture: a city that thrives on its international diversity, where eclectic inner city neighborhoods and master-planned suburban communities come together. Houston is a place where all of us can feel at home. Even with our successes, Houston faces many challenges: from managing its continued growth, to sustaining quality infrastructure, enhancing its existing neighborhoods, and addressing social and economic inequities. Overcoming these challenges requires strong and effective local government, including a City organization that is well-coordinated, pro-active, and efficient. Having this kind of highly capable City is vital to ensuring our community enjoys the highest possible quality of life and competes successfully for the best and brightest people, businesses, and institutions. In short, achieving Houston’s full potential requires a plan. Realizing this potential is the ambition of Plan Houston. In developing this plan, the project team, led by the City’s Planning and Development Department, began by looking at plans that had previously been created by dozens of public and private sector groups. The team then listened to Houstonians themselves, who described their vision for Houston’s future. Finally, the team sought guidance from Plan Houston’s diverse leadership groups – notably its Steering Committee, Stakeholder Advisory Group and Technical Advisory Committee – to develop strategies to achieve the vision. Plan Houston supports Houston’s continued success by providing consensus around Houston’s goals and policies and encouraging coordination and partnerships, thus enabling more effective government. -

MP1) FY 2008 to FY 2012

A Summary of Campus Master Plans (MP1) FY 2008 to FY 2012 July 2008 Division of Planning and Accountability Finance and Resource Planning Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board Robert W. Shepard, CHAIR Harlingen A.W. “Whit” Riter III, VICE CHAIR Tyler Elaine Mendoza, SECRETARY OF THE BOARD San Antonio Charles “Trey” Lewis III, STUDENT REPRESENTATIVE Houston Laurie Bricker Houston Fred W. Heldenfels IV Austin Joe B. Hinton Crawford Brenda Pejovich Dallas Lyn Bracewell Phillips Bastrop Robert V. Wingo El Paso Raymund A. Paredes, COMMISSIONER OF HIGHER EDUCATION Mission of the Coordinating Board Thhe Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board’s mission is to work with the Legislature, Governor, governing boards, higher education institutions and other entities to help Texas meet the goals of the state’s higher education plan, Closing the Gaps by 2015, and thereby provide the people of Texas the widest access to higher education of the highest quality in the most efficient manner. Philosophy of the Coordinating Board Thhe Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board will promote access to quality higheer education across the state with the conviction that access without quality is mediocrity and that quality without access is unacceptable. The Board will be open, ethical, responsive, and committed to public service. The Board will approach its work with a sense of purpose and responsibility to the people of Texas and is committed to the best use of public monies. The Coordinating Board will engage in actions that add value to Texas and to higher education. The agency will avoid efforts that do not add value or that are duplicated by other entities. -

Environmental Chemistry What Can I Do with This Major?

Chemistry - Environmental Chemistry What can I do with this major? Related Career Titles Search for potential careers/jobs with these position titles. What is B.S. in Chemistry with • Environmental Activist Environmental Chemistry? • Environmental Consultant • • • • Agricultural Agent The Bachelor of Science in Chemistry • Environmental Scientist with a concentration in • Biochemist Environmental Chemistry is • Ecologist particularly appropriate for students’ • Environmental Lawyer interested working in the chemistry • Environmental Regulator industry, state regulatory agencies • Chemical Engineer involved in environmental monitoring, • Toxicologist as well as graduate studies in chemistry • Waste Management Technician and environmental sciences. Topics • Soil Scientist that are of interest to this major are • Pollution Engineer radioactivity, carbon dioxide levels, • Range Manager endangered species and toxic chemicals. Some of the courses Professional Organizations included in this area are organic Affiliate yourself with groups to network and learn about the field chemistry, physical chemistry, geology, quantitative analysis and biochemistry. Chemistry Club, UHD group Center for Urban Agriculture & Sustainability, UHD Interested in discussing your American Chemical Society career path possibilities? Texas Association of Environmental Professionals Visit S-402 or Call 713-221-8980 Explore Career Specific Websites The Career Development Center www.acs.org|www.environmentalscience.org/ | www.aacc.org/ | www.setac.org/ | www.asm.org -

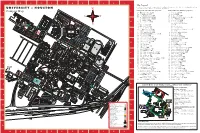

Campus Map with Legend

Map Legend For your convenience, we’ve provided the map legend in this format: buildings are listed in numerical order according to the corresponding numbers on the map, followed by the building name, abbreviation of the building name, and (grid position). Building number, name, abbreviation, (grid position) Building number, name, abbreviation, (grid position) 523 Allied Geophysical Labs, AGL (G8) 531 Hofheinz Pavilion, HP (H4) 509 M.D. Anderson Library, L (F7) 539 Krost Hall, KH (G9) 505 J. Davis Armistead Building, JDA (B8) 555 Law Residence Hall, LH (D4) 12A 578 Agnes Arnold Auditorium 1, AUD1 (G6) 599 Carl Lewis International Track and Field Complex (J4) 12 SCOTT STREET Agnes Arnold Auditorium 2, AUD2 (G6) 588 Charles F. McElhinney Hall, M (F4) Agnes Arnold Hall, AH (F6) 533 Melcher Gymnasium, MEL (I4) 111 573/ Athletics/Alumni Center, AAF (I4) 536 The LeRoy and Lucile Melcher 11B 574 Center for Public Broadcasting,-CPB (I9) 560 537 Bates Law Building, BL (G9) KUHT-TV, TV 12B 557 Bates Residence Hall, BH (E4) KUHT-TV TV Production, P2 500 Bayou Oaks Apartments (A7) KUHF-TV Film Production, P1 562 A.D. Bruce Religion Center, ADB (E5) Development/Association for Community Television, ACT 10 597 Cambridge Oaks Apartment, CO (D2) KUHF-FM, COM 9B 586 Isabel C. Cameron Building, CAM (D3) 528 LeRoy and Lucile Melcher Hall, MH (E8) 10A 11A 522 Campus Recreation and Wellness Center, CWR (C9) 584 Moody Towers, MR (C7) 9C 504 Child Care Center, CCC (E2) 520 Rebecca and John J. Moores 15D 598 Clinical Research Center, CRS (C3) School of Music Building,-MSM-(H6) T EE R 543 College of Architecture Building, ARC (H8) 559 E.E. -

Spring 2019 Parkside Hermann Park Conservancy Newsletter

SPRING 2019 PARKSIDE HERMANN PARK CONSERVANCY NEWSLETTER 1&10 in the park Coming Soon: The Commons at COMING SOON: Hermann Park 2 The Commons at Hermann Park MVVA From the President 3&11 Creating a Space for all Houstonians 4 Holocaust Museum ‘Coexistence’ Exhibit Sponsor Spotlight 5 Love Your Park 6–7 Hats in the Park 8–9 Kite Festival 12 Park to Port 13 Run in the Park 14 Stonyfield Organic, Walmart, and Hermann Park Conservancy Team Up to Go Organic 15 One of the primary features of the Commons at Hermann Park will be an innovative “play garden” with whimsical play structures for Save the Dates! children of all ages. Houston is a very different city than it at the heart of the upcoming Innovation was in 1914, the year Hermann Park was Corridor—with the tech startups to the created. It is, of course, much larger and north in Midtown and the TMC3 research more diverse than anyone could have complex to the south along Brays Bayou. ever imagined. The neighborhoods With this prime location, this new project’s surrounding Hermann Park have also goal is to be a gathering place for all HATS IN THE PARK evolved and grown in that century. Houstonians, from families and university see pages 6-7 The needs and wants of Hermann Park’s students to tech workers and medical neighbors and Houstonians at large have researchers. changed dramatically, nearly as much MISSION Hermann Park Conservancy has always Hermann Park as this city’s many skylines. had one mission: maintain and improve Conservancy is a In that spirit, Hermann Park Conservancy the Park for generations to come. -

Sponsorship Opportunities

Sponsorship Opportunities The Hermann Park Conservancy Kite Festival is a free, public event that brings families and the greater Houston community together to enjoy a day in Hermann Park. Hermann Park Conservancy Kite Festival Sunday, March 25, 2018 10 a.m. - 5 p.m. Born from Hermann Park’s centennial celebrations in 2014, Kite Festival was so popular that it has become an annual community event. Now in it’s fifth year, the festival brings nearly 10,000 kite flyers to Houston’s historic Hermann Park to enjoy a day of friendly kite-flying, arts and crafts, music, activities and more - all free and open to the public. Activities include: • Live music, DJs, and student performances • Friendly kite-flying and kite crafts • Interactive games and activities • Partnerships with local organizations, and much more! Learn more at hermannpark.org/kitefestival Sponsorships of all levels are available for this day of kite flying and fun in Hermann Park. Your sponsorship supports Hermann Park Conservancy’s stewardship and improvement initatives and helps us to continue to bring community-based programming to Hermann Park, one of Houston’s largest and most loved urban parks. ABOUT HERMANN PARK Founded in 1914 by Houston businessman and philanthropist, George Hermann, Hermann Park is a 445-acre greenspace in the heart of Houston’s vibrant museum district and is one of the most visited and historic Parks in the City. The verdent greenspace features The Buddy Carruth Playground for All Children, a traditional Japanese Garden, the Hermann Park Railroad, numerous running trails, the stunning McGovern Centennial Gardens, and countless other points of interest that serve as the backdrop for innumerable Houstonians’ lifetime memories. -

Iller Utdoor Heatre

M M ILLER 2035 O O UTDOOR MASTER PLAN T HEATRE June 22, 2015 DRAFT M M ILLER 2035 O O UTDOOR MASTER PLAN T T HEATRE Prepared by: CLIENT Houston First Corporation CONSULTANT TEAM SWA Group James Vick Christopher Gentile Tarana Hafiz Maribel Amador Studio Red Architects Pete Ed Garrett Liz Ann Cordill Schuler Shook Jack Hagler Alex Robertson 2035 MASTER PLAN “Great cities are defined by the institutions that elevate the consciousness of their citizens through the preservation and advancement of the local culture. Since 1923, Miller Outdoor Theatre has been a standout. As it approaches its centennial, Miller Outdoor Theatre serves an ever- growing and diverse community with the Prepared by: very best in performing arts programming in an open and free venue. With this Master Plan, Miller Outdoor Theatre has a guide with which to sustain and enhance CLIENT the MOT experience for Houstonians and Houston First Corporation visitors well into the future.” CONSULTANT TEAM Dawn R. Ullrich SWA Group President and CEO, Houston First Corporation James Vick Christopher Gentile Tarana Hafiz Maribel Amador Studio Red Architects Pete Ed Garrett Liz Ann Cordill Schuler Shook Jack Hagler Alex Robertson ONTENTS Executive Summary 6 Introduction 9 Background 15 • REGIONAL SITE CONDITIONS • CONTEXTUAL SITE CONDITIONS • LOCAL SITE CONDITIONS • PROGRAMMATIC ELEMENTS • CIRCULATION • THEATRE CONDITIONS • THEATRE STRUCTURE • THEATRE ATTRIBUTES • MOT ORGANIZATION CHART Miller Outdoor Theatre Today 25 • MOT 2035 MASTER PLAN VISION STATEMENT • GOALS + OBJECTIVES • PLANNING