A Danish Journal of Film Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Human Essence and Social Relations from Dogville

Journal of Sociology and Social Work June 2021, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 32-36 ISSN: 2333-5807 (Print), 2333-5815 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jssw.v9n1a4 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/jssw.v9n1a4 Rethinking Human Essence and Social Relations from Dogville Paulo Alexandre e Castro1 Abstract One of the main reasons why Dogville (2003), by Lars Von Trier became a famous film, was the way it was filmed, that is, the way Lars Von Trier created a totally new aesthetic in filming, by providing a scenario that represents reality. In fact, this is the right word, scenario, but it‟s not just that. With this particular way of filming, Lars Von Trier provides also a particular way of thinking, that is, he ends up reproducing the way of seeing with the imagination: creating presence in the absence, as happens when we remember a deceased relative or when we create artistically. In Dogville there is no room for imagination. In this sense, we argue that this film represents contemporary (alienated) society where everything has its value and ethical / moral values are only manifested paradoxically as a reaction. Dogville becomes also an aesthetic educational project since it provides an understanding of human condition and human nature. For this task we will make use of some major figures from contemporary philosophy and sociology Keywords: Lars Von Trier; Human nature; Subjectivity; Values; Violence; Dogville; Society. 1. Introduction: Lars Von Trier and Dogma95 challenge Making movies is not making beautiful movies. -

Pernille Fischer Christensen

A FAMILY EEN FILM VAN Pernille Fischer Christensen WILD BUNCH HAARLEMMERDIJK 159 - 1013 KH – AMSTERDAM WWW.WILDBUNCH.NL [email protected] WILDBUNCHblx A FAMILY – Pernille Fischer Christensen PROJECT SUMMARY Een productie van ZENTROPA Taal DEENS Originele titel EN FAMILIE Lengte 99 MINUTEN Genre DRAMA Land van herkomst DENEMARKEN Filmmaker PERNILLE FISCHER CHRISTENSEN Hoofdrollen LENE MARIA CHRISTENSEN (Brothers, Terribly Happy) JESPER CHRISTENSEN (Melancholia, The Young Victoria, The Interpreter) PILOU AESBAK (Worlds Apart) ANNE LOUISE HASSING Release datum 4 AUGUSTUS 2011 DVD Release 5 JANUARI 2012 Awards/nominaties FILM FESTIVAL BERLIJN 2010 NOMINATIE GOUDEN BEER WINNAAR FIPRESCI PRIJS Kijkwijzer SYNOPSIS Ditte Rheinwald vertegenwoordigt de jongste generatie van de beroemde Deense bakkersfamilie. Haar eigen dromen en ambities zijn echter anders dan die van haar familie. Als ze een droombaan bij een galerie in New York krijgt aangeboden, besluit ze samen met haar vriend Peter de kans aan te grijpen. De toekomst lijkt stralend, het leven vrolijk en simpel. Maar dan wordt Ditte’s charismatische vader Rikard, meesterbakker en hofleverancier, ernstig ziek. Als Rikard eist dat zij de leiding overneemt van het familiebedrijf, raakt haar hele leven uit balans. Plotseling is het leven niet meer zo simpel. CAST Ditte Lene Maria Christensen Far Jesper Christensen Peter Pilou Asbæk Sanne Anne Louise Hassing Chrisser Line Kruse Line Coco Hjardemaal Vimmer Gustav Fischer Kjærulff CREW DIRECTOR Pernille Fischer Christensen SCREENWRITERS Kim Fupz -

SEQUENCE 1.2 (2014) an Allegory of a 'Therapeutic' Reading of a Film

SEQUENCE 1.2 (2014) An Allegory of a ‘Therapeutic’ Reading of a Film: Of MELANCHOLIA Rupert Read SEQUENCE 1.2 (2014) Rupert Read Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: 6.43 If good or bad willing changes the world, it can only change the limits of the world, not the facts; not the things that can be expressed in language. // In brief, the world must thereby become quite another, it must so to speak wax or wane as a whole. // The world of the happy is quite another than that of the unhappy. 6.431 As in death, too, the world does not change, but ceases. 6.4311 Death is not an event of life. Death is not lived through. // If by eternity is understood not endless temporal duration but timelessness, then he lives eternally who lives in the present. // Our life is endless in the way that our visual field is without limit. Heidegger, Being and Time: If I take death into my life, acknowledge it, and face it squarely, I will free myself from the anxiety of death and the pettiness of life - and only then will I be free to become myself. Wittgenstein, Remarks on the philosophy of psychology I: 20: [A]n interpretation becomes an expression of experience. And the interpretation is not an indirect description; no, it is the primary expression of the experience. 2 SEQUENCE 1.2 (2014) Rupert Read 1. This essay is a (more or less philosophical) i. Throughout this paper, I dance in a account or allegory of my viewing(s) of Lars von ‘dialogue’ with – am in ‘conversation’ Trier’s remarkable film, Melancholia (2011).1 It is with – Steven Shaviro’s fascinating personal, and philosophical. -

Members Only Screenings 2006

Films Screened at MFS ‘Members Only’ Nights, Masonic Hall Maleny February ’06 to Dec ’16 ’10 84 Charing Cross Road US drama 1986 ’12 100 Nails ITALY drama 2007 ’14 400 Blows FR drama 1959 ’09 The Archive Project AUS doc 2005 ’07 The Back of Beyond AUS drama 1954 ’08 Babakiueria AUS com 1986 ’14 Barbara GER psych.thriller 2012 ’15 My Beautiful Country GER drama 2012 (Die Brücke am Ibar) ’07 Bedazzled UK comedy 1967 ’11 Black Orpheus BRAZIL/FR drama 1958 ’11 Blow Up UK drama 1966 ’10 Bootmen US/AUS drama 2000 ’16 Bornholmer Street Germany drama 2014 ’16 Breaker Morant AUS drama 1980 ’06 Breaking the Waves US dr/rom 1996 ’12 Breathless (A Bout de Souffle) FR drama 1959 ’09 Brothers Denmark drama 2004 ’13 Bunny Lake is Missing UK mystery/dr 1965 ’07 Cane Toads AUS doc 1987 ’16 Casablanca US drama 1942 ’12 Cherry Blossoms Germany drama 2008 ’06 The Chess Players India drama 1977 ’12 Children of the Revolution AUS drama 1996 ’08 The Company of Strangers Canada drama 1990 ’13 Cul de Sac UK mystery/com 1966 ’06 Cunnamulla AUS doc 2000 ’06 Dance of the Wind INDIA drama 1997 ’09 Dancer in the Dark Denmark musical 2000 ’10 Day for Night FR comedy 1973 ’09 Days of Heaven USA drama 1978 ’16 Dead Poet’s Society USA com/dr 1989 ’11 Dingo AUS jazz/dr ama 1991 ’11 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie FR satire 1972 ’13 Distant Lights GER immigrant dr 2003 ’11 Il Divo ITALY political dr 2008 ’08 Don’s Party AUS com/drama 1976 ’15 The Dunera Boys AUS doc 1985 ’07 East of Eden US drama 1954 ’07 The Edge of the World/ Scotland doco 1937/ Return to the Edge -

Chinese, US Textile Companies Share Worldview

Tuesday, July 18, 2017 CHINA DAILY USA 2 ACROSS AMERICA Chinese, US textile companies share worldview By AMY HE in New York the center of textile and appar- clients are taking interest in our [email protected] el production in China, have designs — the newer, trendier their own exhibition area at the and unique designs,” he said. The Chinese and American Javits Center. Zhou said that the industry textile industries are collaborat- “Today, China is the US’ larg- is a tough one to work in now, ing more closely than ever as est trading partner—our bilat- as it recovers from a worldwide the US becomes a “key player eral trade, bilateral investment, slump the past few years. in the international strategy” of and people-to-people exchanges “We work with smaller China’s textile companies, said have all reached historic highs, brands now, collaborating with Xu Yingxin, vice-president of and in this connection, I think them directly, like with Jones the China National Textile and the textile industry has made big New York and Andrew Marc. Apparel Council. contributions to this growth,” The clients may order less prod- “The United States is not just said Zhang Qiyue, Chinese con- uct, but the prices of the pieces a key trading partner with Chi- sul general in New York. are higher, and so we’re earning na in the textile industry; it is “The textile cooperation has more profi t,” he said. also a key player in the interna- not just brought tangible ben- China Textiles Development tional strategy of China’s textile efi ts to our two peoples, it has Center, based in Beijing, is a industry,” Xu said on Monday also contributed to global eco- new participant to the textile at the opening ceremony of nomic growth,” she said. -

Nature and the Feminine in Lars Von Trier's Antichrist

PARRHESIA NUMBER 13 • 2011 • 177-89 VIOLENT AFFECTS: NATURE AND THE FEMININE IN LARS VON TRIER’S ANTICHRIST Magdalena Zolkos [Of all my films] Antichrist comes closest to a scream. Lars von Trier INTRODUCTION / INVITATION: “THE NATURE OF MY FEARS”1 Lars von Trier’s 2009 film Antichrist, produced by the Danish company Zentropa, tells a story of parental loss, mourning, and despair that follow, and ostensibly result from, the tragic death of a child. The film stars two protagonists, identified by impersonal gendered names as She (Charlotte Gainsbourg) and He (Willem Dafoe). This generic economy of naming suggests that Antichrist, in spite of, or perhaps because of, the eschatological signification of its title, is a story of origins. Antichrist stages a quasi-religious return (within the Abrahamic tradition) to a lapsarian space where the myth of the female agency of the originary transgression,2 and the subsequent establishment of human separateness from nature, are told by von Trier as a story of his own psychic introspection. In the words of Joanne Bourke, professor of history at Birkbeck College known for her work on sexual violence and on history of fear and hatred, Antichrist is a re-telling of the ancient Abrahamic mythology framed as a question “what is to become of humanity once it discovers it has been expelled from Eden and that Satan is in us.”3 This mythological trope grapples with the other-than-human presence, as a demonic or animalistic trace, found at the very core of the human.4 At the premiere of Antichrist at the 2009 -

Tom Hanks Halle Berry Martin Sheen Brad Pitt Robert Deniro Jodie Foster Will Smith Jay Leno Jared Leto Eli Roth Tom Cruise Steven Spielberg

TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND MARION COTILLARD KIRSTEN DUNST STEVE BUSCEMI ELIJAH WOOD RESSE WITHERSPOON MICKEY ROURKE AUDREY HEPBURN STEVE CARELL AL PACINO JIM CARREY SHARON STONE MEL GIBSON 2017-18 CATALOG SAM NEILL CHRIS HEMSWORTH MICHAEL SHANNON KIRK DOUGLAS ICE-T RENEE ZELLWEGER ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG CONTENTS 2 INDEPENDENT | FOREIGN | ARTHOUSE 23 HORROR | SLASHER | THRILLER 38 FACTUAL | HISTORICAL 44 NATURE | SUPERNATURAL MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN 45 WESTERNS SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO 48 20TH CENTURY TELEVISION LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA 54 SCI-FI | FANTASY | SPACE DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW 57 POLITICS | ESPIONAGE | WAR SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST 60 ART | CULTURE | CELEBRITY MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE 64 ANIMATION | FAMILY WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND 78 CRIME | DETECTIVE -

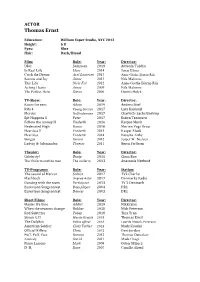

Thomas Ernst

ACTOR Thomas Ernst Education: William Esper Studio, NYC 2012 Height: 6 ft Eyes: Blue Hair: Dark/Blond Film: Role: Year: Director: URO Salesman 2019 Antonio Tublén In Real Life Marc 2014 Jonas Elmer Catch the Dream Axel Lauersen 2013 Anne-Grethe Bjarup Riis Sorrow and Joy Jønne 2013 Nils Malmros This Life Niels Fiil 2012 Anne-Grethe Bjarup Riis Aching Hearts Jonas 2009 Nils Malmros The Perfect Heist Simon 2006 Dennis Holck TV-Show: Role: Year: Director: Room for rent Adam 2019 Andrea Stief Rita 4 Young Carsten 2017 Lars Kaalund Mercur Ib Glindemann 2017 Charlotte Sachs Bostrup Sjit Happens 5 Peter 2017 Esben Tønnesen Follow the money II Frederik 2016 Kaspar Munk Hedensted High Kaare 2016 Morten Vogt Urup Heartless II Frederik 2015 Kaspar Munk Heartless Frederik 2014 Natasha Arthy Borgen Dennis 2012 Jesper W. Nielsen Ludvig & Julemanden Thomas 2011 Søren Frellesen Theater: Role: Year: Director: Celebrity! Dusty 2015 Claus Bue The Uniform and the man The uniform 2013 Anastasia Nørlund TV-Programs: Role: Year: Station: The sound of Mercur Soloist 2017 TV2 Charlie Flashback ImproV Actor 2017 Danmarks Radio Dancing with the stars Participant 2013 TV 2 Denmark EuroVison Songcontest Bass player 2004 DR1 EuroVison Songcontest Dancer 2003 DR1 Short Films: Role: Year: Director: Maybe it’s time Addict 2019 Nikki Sixx When the seasons change Robber 2018 Nick Peterson Red Subtitles Tobey 2018 Tina Tran Simon G.H Martin Krofelt 2018 Thomas Ernst The Dolphin Police officer 2018 Laurits Munch-Petersen American Soldier Chris Tucker 2015 Mads Koudal Official Killers Chris 2015 Deni Jordan Puff, Puff, Pass Rasmus 2012 Thomas Daneskov Zomedy David 2011 Mads Grage Piano Lessons Mark 2009 Gabor Mihucz D+R Rune 2007 Camille Alsted Training: Berg Studios, Los Angeles, CA – w. -

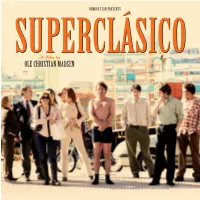

Ole Christian Madsen – 02 – Synopsis

NIMBUS FILM PRESENTS A Film by OLE CHRISTIAN MADSEN – 02 – SYNOPSIS – 03 – Christian (Anders W. Berthelsen) is the owner of a wine store that is about to go bankrupt and he is just as unsuccessful in just about every other aspect of life. His wife, Anna (Paprika Steen), has left him. Now, she works as a successful football agent in Buenos Aires and lives a life of luxury with star football player Juan Diaz. One day, Christian and their 16-year-old son get on a plane to Buenos Aires. Christian arrives under the pretense of wanting to sign the divorce papers together with Anna, but in truth, he wants to try to win her back! – 04 – COMMENTS FROM THE DIRECTOR Filmed in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Superclásico is a Danish comedy set in an exotic locale. And the wine, the tango and the Latin tempers run high – when Brønshøj meets Buenos Aires! This is the first time that a Danish film crew has shot a feature film in Argentina, and it has been a great source of experience and inspiration not least for director Ole Christian Madsen for whom Superclásico is also his debut as a comedy director. The following is an interview with Ole Christian Madsen by Christian Monggaard. Life is a party A film about love ”You experience a kind of liberation in Argentina,” ”Normally, when you tell the story of a divorce, says Ole Christian Madsen about his new film, the you focus on the time when you sit and nurse your comedy Superclásico, which takes place in Buenos emotional wounds. -

Year in Review

2015 Year in Review www.paulsoninstitute.org Our Mission Our mission is to strengthen U.S.-China relations by advancing sustainable economic growth and environmental protection in both countries. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN CONTENTS Message from the Chairman Friends, Five years ago, we launched the Paulson Institute with the recognition that it would be difficult but vitally important to keep the U.S.-China bilateral relationship on an even keel to make progress toward solving the economic, environmental, national security and geopolitical challenges facing the world today. 2015 is a case in point, with the relationship stretched interests into complementary policies is not easy. Contents by tensions ranging from the South China Sea to the I see historic opportunities for the United States and cyber realm and through a growing sense by U.S. China to take concrete actions to address global businesses that they are encountering mounting problems: opportunities to collaborate on regulatory barriers in China. We’ve also seen some environmental solutions and new energy technologies, important bright spots, including a successful Paris on eliminating tariffs on environmental goods and 2 14 conference in December following a breakthrough services, and to develop new models for green A Letter from the Sustainable Economic U.S.-China climate change agreement, as well as the finance as China prepares to host the G-20 leaders Leadership Transition State Visit by President Xi Jinping to the United States meeting in September; opportunities to make our in September. economies more complementary—as each side 2016 is shaping up to be a difficult year, with the undertakes necessary restructuring—and to make global economy bogged down by slowing growth progress on or maybe even complete a Bilateral 4 28 in emerging markets and advanced industrial Investment Treaty; and above all, opportunities Promoting Stronger Harnessing the Power countries. -

British Society of Cinematographers

Best Cinematography in a Theatrical Feature Film 2020 Erik Messerschmidt ASC Mank (2020) Sean Bobbitt BSC Judas and the Black Messiah (2021) Joshua James Richards Nomadland (2020) Alwin Kuchler BSC The Mauritanian (2021) Dariusz Wolski ASC News of the World (2020) 2019 Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC 1917 (2019) Rodrigo Prieto ASC AMC The Irishman (2019) Lawrence Sher ASC Joker (2019) Jarin Blaschke The Lighthouse (2019) Robert Richardson ASC Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood (2019) 2018 Alfonso Cuarón Roma (2018) Linus Sandgren ASC FSF First Man (2018) Lukasz Zal PSC Cold War(2018) Robbie Ryan BSC ISC The Favourite (2018) Seamus McGarvey ASC BSC Bad Times at the El Royale (2018) 2017 Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC Blade Runner 2049 (2017) Ben Davis BSC Three Billboards outside of Ebbing, Missouri (2017) Bruno Delbonnel ASC AFC Darkest Hour (2017) Dan Laustsen DFF The Shape of Water (2017) 2016 Seamus McGarvey ASC BSC Nocturnal Animals (2016) Bradford Young ASC Arrival (2016) Linus Sandgren FSF La La Land (2016) Greig Frasier ASC ACS Lion (2016) James Laxton Moonlight (2016) 2015 Ed Lachman ASC Carol (2015) Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC Sicario (2015) Emmanuel Lubezki ASC AMC The Revenant (2015) Janusz Kaminski Bridge of Spies (2015) John Seale ASC ACS Mad Max : Fury Road (2015) 2014 Dick Pope BSC Mr. Turner (2014) Rob Hardy BSC Ex Machina (2014) Emmanuel Lubezki AMC ASC Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014) Robert Yeoman ASC The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) Lukasz Zal PSC & Ida (2013) Ryszard Lenczewski PSC 2013 Phedon Papamichael ASC -

Submarino / Berlinale Competition a Family/ Berlinale Competition Super

vINTErBErG rETUrNS To rEALISM family entanglements ADMIratioN For THE oUTSIDEr The director of Festen/The Celebration, Thomas Berlin winner for A Soap, Pernille Fischer Christensen This tagline could well describe the spirit of the stories Vinterberg brings his latest filmSubmarino to the is back competing at the Berlinale with A Family. At the in the five films chosen by Berlinale’s Generation: Birger Berlinale Competition. A story about two estranged heart of the story about family ties is the relationship Larsen’s Super Brother and four short films,Megaheavy, brothers marked by an early tragedy. between a father and his daughter. Out of Love, Sun Shine and Whistleless. PAGE 3 PAGE 6 PAGE 9 & 15-20 FILM IS PUBLISHED BY #THE DANISH FILM68 INSTITUTE / febuarY 2010 submarino / Berlinale competition a family / Berlinale competition super brother / Berlinale Generation megaheavy / out of love / sun shine / whistleless / Generation short films PAGE 2 / FILM#68 / BERLIN ISSUE FILM#68/ BERLIN issue insiDe vINTErBErG rETUrNS To rEALISM FAMILY ENTANGLEMENTS ADMIrATIoN For THE oUTSIDEr ESSENTIAL BoNDS / BErLINALE CoMPETITIoN The director of Festen/The Celebration, Thomas Berlin winner for A Soap, Pernille Fischer Christensen This tagline could well describe the spirit of the stories Vinterberg brings his latest filmSubmarino to the is back competing at the Berlinale with A Family. At the in the five films chosen by Berlinale’s Generation: Birger Berlinale Competition. A story about two estranged heart of the story about family ties is the relationship Larsen’s Super Brother and four short films,Megaheavy, brothers marked by an early tragedy. between a father and his daughter.