Genesis 22, the Masoretic Text, and Targum Onkelos 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

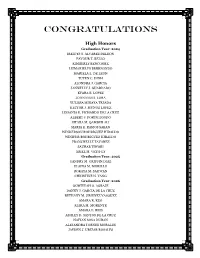

Congratulations

CONGRATULATIONS High Honors Graduation Year: 2024 IREIDYS Y. ALVAREZ DELEON FAVOUR T. BELLO KIMBERLY BENCOSME LIZMARIELYS BERREONDO MARIELA L. DE LEON TUYEN C. DINH ALONDRA J. GARCIA JANNELLY J. GUARDADO KYARA E. LOPEZ JOHNANGEL LORA YULISSA MINAYA TEJADA HECTOR J. MUNOZ LOPEZ LISSANIA E. PICHARDO DE LA CRUZ ALBERT J. PORTUHONDO SITARA M. QAMBER ALI MARIA E. RAMOS SABAN WINDERSON RODRIGUEZ HIRALDO WINIFER RODRIGUEZ HIRALDO FRANCHELLE TAVAREZ SAURAB TIWARI ARIEL M. VETH-LY Graduation Year: 2025 YANDRY M. GRIFFIN DIAZ ELAINA M. MORILLO ROKAYA M. SAHWAN CHRISTINE N. YANG Graduation Year: 2026 QOWIYYAH O. AGBAJE DANNY J. GARCIA DE LA CRUZ BETHANY M. JIMENEZ VASQUEZ AMARA R. KEO KIARA M. MORENTE AMARA E. REIS ASHLEY D. SANTOS DE LA CRUZ NAIYAN SOSA DURAN ALEJANDRA TORNES MORALES JAYDEN J. URIZAR ROSALES Honors Graduation Year: 2024 JOSELYN E. ALONZO XAVIEA S. BROWN PRECIOUS F. BUWEE WILBERT CABRAL GARCIA KALIYAN N. CHHUN JUANA CHIJAL JESSICA A. CHOCOJ CHALI DOMINGO COLAJ COLAJ MARIALYS I. CRUZ ASHLEY M. DE LA CRUZ ARIAS ARDENIS J. DEL ROSARIO GIANA N. DICENZO BRIANNA M. DOMINGUEZ FRIAS SOMALY DONG OSMERY ESTRELLA VARGAS ERICA O. FELIX HERRERA EDUARDO J. GIL ALFONSO BRYAN M. GIRON LUX VILMA GODINEZ SEBASTIANA JERONIMO ALONZO HENRY L. JOHNSON IV TATYANA JOHNSON KRISSBEILY MARTE FERREIRA GEARA D. MATOS DIEGO A. NAVAS ORTES OLIVIER NGABONZIZA MANUELA NUNEZ HERNANDEZ AMBER K. O'BRIEN NICERLIS OLIVO NUNEZ ANDERSON E. ORTEGA-LOPEZ YENEDELI E. PENA GUZMAN FRANCISCO PEREZ RAMOS RENE G. REYES EMILY A. RINDA BETHZY M. ROBLES URIZAR CRISTIAN D. ROSALES HERNANDEZ JASON S. RUSH JAMES D. SEFFENS III GENESIS SOSA ALEXANDER SUAREZ LIZZETTE M. -

Evaluation & Research Literature: the State of Knowledge on BJA

Evaluation & Research Literature: The State of Knowledge on BJA-Funded Programs March 27, 2015 Overview The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) is a leader in developing and implementing evidence-based criminal justice policy and practice. BJA’s mission is to provide leadership in services and grant administration and criminal justice policy development to support local, state, and Tribal justice strategies to achieve safer communities. This is accomplished in many criminal justice topic areas, including adjudication, corrections, counter-terrorism, crime prevention, justice information sharing, law enforcement, justice and mental health, substance abuse, and Tribal justice. Under each topic area, BJA funds numerous programs and initiatives at the Tribal, local, and state level. In partnership with the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), other Federal partners, and many other research partners, many of these programs have been evaluated, while others have not. The intent of the following report is to assess the state of knowledge as determined by data collection, research, and evaluation of and related to BJA- funded programs. This report is a resource that can be a reference for both evaluation and research literature on many BJA programs. It also identifies programs and practices for which U.S. Department of Justice resources have played a critical role in generating innovative programs and sound practices. This report identifies programs and practices with a solid foundation of evidence, as well as those that may benefit from further research and evaluation. Program evaluation is a systematic, objective process for determining the success of a policy or program. Evaluations assess whether and to what extent the program is achieving its goals and objectives. -

Genesis, Book of 2. E

II • 933 GENESIS, BOOK OF Pharaoh's infatuation with Sarai, the defeat of the four Genesis 2:4a in the Greek translation: "This is the book of kings and the promise of descendants. There are a num the origins (geneseos) of heaven and earth." The book is ber of events which are added to, or more detailed than, called Genesis in the Septuagint, whence the name came the biblical version: Abram's dream, predicting how Sarai into the Vulgate and eventually into modern usage. In will save his life (and in which he and his wife are symbol Jewish tradition the first word of the book serves as its ized by a cedar and a palm tree); a visit by three Egyptians name, thus the book is called BeriPSit. The origin of the (one named Hirkanos) to Abram and their subsequent name is easier to ascertain than most other aspects of the report of Sarai's beauty to Pharaoh; an account of Abram's book, which will be treated under the following headings: prayer, the affliction of the Egyptians, and their subse quent healing; and a description of the land to be inher A. Text ited by Abram's descendants. Stylistically, the Apocryphon B. Sources may be described as a pseudepigraphon, since events are l. J related in the first person with the patriarchs Lamech, 2. E Noah and Abram in turn acting as narrator, though from 3. p 22.18 (MT 14:21) to the end of the published text (22.34) 4. The Promises Writer the narrative is in the third person. -

Philo Ng.Pdf

PHILO AND THE NAMES OF GOD By A. MARMORSTEIN,Jews College, London IN A recent work on the allegorical exegesis of Philo of Alexandria' Philo's views and teachings as to the Hebrew names of God are once more discussed and analyzed. The author repeats and shares the old opinion, elaborated and propagated by Zacharias Frankel and others that Philo was more or less ignorant of the Hebrew tongue. Philo's treat- ment of the divine names is put in the first line of witnesses to corroborate this literary verdict. This question touches wider and more important problems than the narrow ques- tion whether Philo knew Hebrew, or not,2 and if the former is the case how far his knowledge, and if the latter is true how far his ignorance went. For the theologians generally some important historical and theological problems, for Jewish theology especially, besides these, literary and relig- ious questions as to the date and origin of religious concep- tions, and the antiquity and value of our sources are involved. Philo is criticized for having no idea2 of the equivalent names used by the LXX for the Tetragrammaton and Elohim respectively. The former is translated KVptOS, the latter 4hos. This omission is the more serious since the distinction between these two names is one of Philo's chief doctrines. We are referred to a remark made by Z. Frankel about ' Edmund Stein, Die allegorische Exegese des Philo aus Alexandreia; Giessen, 1929. (Beihefte Zur ZAW. No. 51.) 2 Ibid., p. 20, for earlier observations see G. Dalman, Adonaj, 59.1, Daehne, Geschichtliche Darstellung, I 231, II 51; Freiidenthal, Alexander Polyhistor, p. -

In Silence Genesis 22 Some of Life's Deepest Mysteries Are Examined In

In Silence Genesis 22 Some of life’s deepest mysteries are examined in Bible stories. Through the centuries, for example, many have tried to make sense out of the narrative recorded in Genesis 22, one of the darkest, most difficult stories that humans have ever told each other. This account begins with a shout. It’s only one word long. Abraham is at home with his wife, his servants. We don’t know what he’s doing at this moment. It’s probably an ordinary day. When suddenly Abraham hears a voice. The voice says to him one word: “Abraham!” This is not just a voice. This is the voice of God, the Creator of the Universe calling to one man, to Abraham. Not for the first time, not at all. When Abraham was younger, God appeared to him and told him to leave his home, which Abraham did. And then God told Abraham to go to a strange land, which he did. And then God and Abraham exchanged promises, and made a covenant together, and God told Abraham to send his first son Ishmael away into the desert, which Abraham did. And then God told Abraham that he had a plan to destroy the people of Sodom and Gomorrah. This time Abraham argued with God. They went back and forth – Abraham and God. “Can’t we save those cities, or some people in those cities, or anyone in those cities?” Later God sent angels to tell of the coming of Isaac. So it wasn’t completely out of the ordinary when God came to where Abraham was and called to him. -

Humor in Torah and Talmud, Part 5

Sat 18 Aug 2018 – 7 Elul 5778 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Lunch and Learn Humor in Torah and Talmud, Part 5 Torah (Theme: God is angry at us) 1-God loses it [The Israelites repeatedly ask Moses for meat in the desert. God tells Moses:] And say to the people... you shall eat meat. You shall not eat it for one day, or two days, or five days, or ten days, or twenty days; but for a whole month, until it comes out of your nostrils and you become disgusted by it. [Numbers 11:18-20] 2-This, too, shall happen to you! The most dreaded Torah portion is Ki Tavo, where God lists all the curses that will befall those who do not follow His commandments: But it shall come to pass, if you will not listen to the voice of the Lord your God, to take care to do all his commandments and his statutes which I command you this day, that all these curses shall come upon you and overtake you. [Deut. 28:15] Follows a long string of dreaded curses, beginning with: Cursed shall you be in the city, and cursed shall you be in the field… [Deut. 28:16] And ending with: Also, every illness and every plague, that is not written in this Book of the Torah, the Lord will bring it upon you, until you are destroyed. [Deut 28:61] It’s not even exclusive: Whatever you dread most, whatever it is, shall happen to you! 3-Moses’ masterful plea The Israelites revert to idolatry by building and worshiping the Golden Calf. -

Shavuot Daf Hashavua

בס״ד ׁשָ בֻ עוֹת SHAVUOT In loving memory of Harav Yitzchak Yoel ben Shlomo Halevi Volume 32 | #35 Welcome to a special, expanded Daf Hashavua 30 May 2020 for Shavuot at home this year, to help bring its 7 Sivan 5780 messages and study into your home. Chag Sameach from the Daf team Shabbat ends: London 10.09pm Sheffield 10.40pm “And on the day of the first fruits…” Edinburgh 11.05pm Birmingham 10.22pm (Bemidbar 28:26) Jerusalem 8.21pm Shavuot starts on Thursday evening 28 May and ends after Shabbat on 30 May. An Eruv Tavshilin should be made before Shavuot starts. INSIDE: Shavuot message Please look regularly at the social media and websites by Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis of the US, Tribe and your community for ongoing updates relating to Coronavirus as well as educational programming Megillat Rut and community support. You do not need to sign by Pnina Savery into Facebook to access the US Facebook page. The US Coronavirus Helpline is on 020 8343 5696. Mount Sinai to Jerusalem to… May God bless us and the whole world. the future Daf Hashavua by Harry and Leora Salter ׁשָ בֻ עוֹת Shavuot Shavuot message by Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis It was the most New York, commented that from stunning, awe- here we learn that the Divine inspiring event revelation was intended to send a that the world has message of truth to everyone on ever known. Some earth - because the Torah is both three and a half a blueprint for how we as Jews millennia ago, we should live our lives and also the gathered as a fledgling nation at the foundational document of morality foot of Mount Sinai and experienced for the whole world. -

News Briefs the Elite Runners Were Those Who Are Responsible for Vive

VOL. 117 - NO. 16 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, APRIL 19, 2013 $.30 A COPY 1st Annual Daffodil Day on the MARATHON MONDAY MADNESS North End Parks Celebrates Spring by Sal Giarratani Someone once said, “Ide- by Matt Conti ologies separate us but dreams and anguish unite us.” I thought of this quote after hearing and then view- ing the horrific devastation left in the aftermath of the mass violence that occurred after two bombs went off near the finish line of the Boston Marathon at 2:50 pm. Three people are reported dead and over 100 injured in the may- hem that overtook the joy of this annual event. At this writing, most are assuming it is an act of ter- rorism while officials have yet to call it such at this time 24 hours later. The Ribbon-Cutting at the 1st Annual Daffodil Day. entire City of Boston is on (Photo by Angela Cornacchio) high alert. The National On Sunday, April 14th, the first annual Daffodil Day was Guard has been mobilized celebrated on the Greenway. The event was hosted by The and stationed at area hospi- Friends of the North End Parks (FOTNEP) in conjunction tals. Mass violence like what with the Rose F. Kennedy Greenway Conservancy and North we all just experienced can End Beautification Committee. The celebration included trigger overwhelming feel- ings of anxiety, anger and music by the Boston String Academy and poetry, as well as (Photo by Andrew Martorano) daffodils. Other activities were face painting, a petting zoo fear. Why did anyone or group and a dog show held by RUFF. -

Genesis, Evolution, and the Search for a Reasoned Faith

GENESIS EVOLUTION AND THE SEARCH FOR A REASONED FAITH Mary Katherine Birge, SSJ Brian G. Henning Rodica M. M. Stoicoiu Ryan Taylor 7031-GenesisEvolution Pgs.indd 3 1/3/11 12:57 PM Created by the publishing team of Anselm Academic. Cover art royalty free from iStock Copyright © 2011 by Mary Katherine Birge, SSJ; Brian G. Henning; Rodica M. M. Stoicoiu; and Ryan Taylor. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher, Anselm Academic, Christian Brothers Publications, 702 Terrace Heights, Winona, MN 55987-1320, www.anselmacademic.org. The scriptural quotations contained herein, with the exception of author transla- tions in chapter 1, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible: Catho- lic Edition. Copyright © 1993 and 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 7031 (PO2844) ISBN 978-0-88489-755-2 7031-GenesisEvolution Pgs.indd 4 1/3/11 12:57 PM c ontents Introduction ix .1 Genesis 1 Mary Katherine Birge, SSJ Why Read the Bible in the First Place? 1 A Faithful and Rational Reading of the Bible 6 Oral Tradition and the Composition of the Bible 6 Two Stories, Not One 8 “Cosmogony” and the Ancient Near East 11 Genesis 2–3: The Yahwist Account 12 Disaster: The Babylonian Exile 27 Genesis 1: The Priestly Account 31 .2 Scientific Knowledge and Evolutionary Biology 41 Ryan Taylor Science and Its Methodology 41 The History of Evolutionary Theory 44 The Mechanisms of Evolution 46 Evidence for Evolution 60 Limits of Scientific Knowledge 64 Common Arguments against Evolution from Creationism and Intelligent Design 65 3. -

Introduction

Please provide footnote text Chapter 1 Introduction In the sixteenth and the first half of the seventeenth century Christian printers in Europe published Targum texts and provided them with Latin translations. Four complete polyglot Bibles were produced in this period (1517–1657), each containing more Targumic material than the previous one. Several others were planned or even started, but most plans were hampered by lack of money. And in between, every decade one or more Biblical books in Aramaic and Latin saw the light. This is remarkable, since the Targums were Jewish translations of the Hebrew Bible into Aramaic and scarcely functioned in the Jewish liturgy anymore.1 Jews used them primarily as a means to teach Aramaic in the Jewish educational system.2 Yet, Christian scholars were, as parts of the new human- ist atmosphere, interested in ancient texts and their interpretations. And the Targums were interpretations of the Hebrew Bible, the ultimate source of the Christian Old Testament. Moreover, they were written in Aramaic, a language so close to Hebrew that their Jewish translators must have understood the original text more thoroughly than any scholar brought up in another tongue. In contrast, many scholars of those days objected to the study of Jewish lit- erature, including the Targums. A definition of Targum is ‘a translation that combines a highly literal rendering of the original text with material added into the translation in a seamless manner’.3 Moreover, ‘poetic passages are often expanded rather than translated.’4 Christian scholars were interested in the ‘highly literal rendering’, but often rejected the added and expanded ma- terial. -

The Body and Voice of God in the Hebrew Bible

Johanna Stiebert The Body and Voice of God in the Hebrew Bible ABSTRACT This article explores the role of the voice of God in the Hebrew Bible and in early Jew- ish interpretations such as the Targumim. In contrast to the question as to whether God has a body, which is enmeshed in theological debates concerning anthropomor- phism and idolatry, the notion that God has a voice is less controversial but evidences some diachronic development. KEYWORDS body of God, voice of God, Torah, Targumim, Talmud, anthropomorphic BIOGRAPHY Johanna Stiebert is a German New Zealander and Associate Professor of Hebrew Bible at the University of Leeds. Her primary research interests with regard to the Hebrew Bible are centred particularly on self-conscious emotions, family structures, gender and sexuality. In Judaism and Christianity, which both hold the Hebrew Bible canonical, the question as to whether God has a body is more sensitive and more contested than the question as to whether God has a voice.1 The theological consensus now tends to be that God is incorporeal, and yet the most straightforward interpretation of numerous Hebrew Bible passages is that God is conceived of in bodily, anthropomorphic terms – though often there also exist attendant possibilities of ambiguity and ambivalence. The famil- iar divine statement “let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness” (betsalmēnû kidmûtēnû; Gen. 1:26), for example, seems to envisage – particularly in 1 A version of this paper was presented at “I Sing the Body Electric”, an interdisciplinary day confer- ence held at the University of Hull, UK, on 3 June 2014 to explore body and voice from musicological, technological, and religious studies perspectives. -

Chazal's Metaphoric Approach by Rav Elchan

PARASHAT KEDOSHIM "You Shall Not Place a Stumbling Block Before the Blind": Chazal's Metaphoric Approach by Rav Elchanan Samet 1. Four Interpretations of the Prohibition "You shall not curse the deaf, and you shall not place a stumbling block before the blind. You shall fear your God; I am the Lord." These two prohibitions, of cursing the deaf and leading the blind to stumble, both involve the protection of those particularly vulnerable due to physical disability. Indeed, these two crimes are linked by the single admonition towards the end of the verse: "You shall fear your God." Nevertheless, we will devote our discussion entirely to the second prohibition, addressing the first half of the verse only insofar as it affects our understanding of the second. We present here the four interpretations that have been offered to this verse, in the sequence of their deviation from the simple, straightforward meaning, from closest to furthest: 1. "Blind" refers to an individual who cannot see, and "stumbling block" denotes a physical object, such as a stone or beam, that physically endangers the unsuspecting blind person as he walks. This is the interpretation of the Kuttim, who rejected the Oral Law's extrapolation of Biblical verses. (See Nida 57a, Chulin 3a.) The prohibition according to this approach involves taking unfair advantage of the handicap of another. The earlier prohibition against cursing the deaf would presumably be explained in a similar manner. 2. "Blind" here means anyone, even without any handicap, who does not see the stumbling block placed before him. With respect to this specific danger, he may be considered figuratively "blind." "Stumbling block" refers to a physical trap lying innocuously in one's path, such as a pit with an indiscernible covering.