Wrightsville Borough Comprehensive Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conejohela Flats Dating from the Early 1700S

Conejohela is a term derived from an Indian word — meaning “kettle on a long, upright pole”— and refers to a nearby Native American settlement The Conejohela Flats dating from the early 1700s. The exposed mudflats and shallows around the islands across the river are known as the The shallow waters around the Flats are also habitat for many wetland species. In late Conejohela Flats. Local residents farmed this area before it was flooded in 1929 by the winter and early spring, up to 5,000 Tundra Swans stage here before they migrate north. Safe Harbor Dam. Today, the Flats are prized for some 17,000 migratory shorebirds they Over 30 species of waterfowl have been recorded. Bald Eagles and Ospreys also use the Flats, host annually. As many as 38 species of shorebirds use this area to feed and rest on their primarily between April and September. Terns, herons, egrets, rails, hawks, and owls occur journey to breeding grounds as far north as the Arctic Tundra and wintering grounds here each year as well. In all, a wide assortment of birds coexists in this unique habitat. in South and Central America. Species groups include sandpipers, plovers, godwits, phalaropes, avocet, curlew, stilt, and dowitchers. Non-native purple loosestrife, an invasive and rapidly spreading plant that has no value to wildlife, threatens the mud flats. It crowds out beneficial, native vegetation and transforms mud flats into useless habitat for birds and wildlife. Bald Eagle Peregrine Falcon Stilt Sandpiper Great Blue Heron Semipalmated Sandpiper Caspian Tern Whimbrel Greater Yellowlegs Tundra Swan Harrisburg Middletown Sanderling Goldsboro YOU ARE HERE York Haven Dam Marietta Wrightsville Columbia Short-billed Dowitchher These birds are representative Safe Harbor Dam of the many species that frequent the Conejohela Flats. -

Entire Bulletin

PENNSYLVANIA BULLETIN Volume 28 Number 38 Saturday, September 19, 1998 • Harrisburg, Pa. Pages 4705—4776 Agencies in this issue: Department of Banking Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Department of Corrections Department of Environmental Protection Department of General Services Department of Health Department of Transportation Environmental Hearing Board Health Care Cost Containment Council Human Resources Investment Council Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Legislative Reference Bureau Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission Philadelphia Regional Port Authority Public School Employes’ Retirement Board State Board of Medicine State Board of Podiatry Treasury Department Detailed list of contents appears inside. PRINTED ON 100% RECYCLED PAPER Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporter (Master Transmittal Sheet): No. 286, September 1998 published weekly by Fry Communications, Inc. for the PENNSYLVANIA BULLETIN Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Legislative Reference Bu- reau, 647 Main Capitol Building, State & Third Streets, (ISSN 0162-2137) Harrisburg, Pa. 17120, under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Documents pursuant to Part II of Title 45 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes (relating to publication and effectiveness of Com- monwealth Documents). Subscription rate $82.00 per year, postpaid to points in the United States. Individual copies $2.50. Checks for subscriptions and individual copies should be made payable to ‘‘Fry Communications, Inc.’’ Postmaster send address changes to: Periodicals postage paid at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Orders for subscriptions and other circulation matters FRY COMMUNICATIONS should be sent to: Attn: Pennsylvania Bulletin 800 W. Church Rd. Fry Communications, Inc. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania 17055-3198 Attn: Pennsylvania Bulletin (717) 766-0211 ext. 340 800 W. Church Rd. (800) 334-1429 ext. 340 (toll free, out-of-State) Mechanicsburg, PA 17055-3198 (800) 524-3232 ext. -

EASTERN YORK SCHOOL DISTRICT DIRECTORY BOARD of EDUCATION SCHOOL TIME SCHEDULE Mark Keller

AUGUST 2012 SEPTEMBER 2012 OCTOBER 2012 NOVEMBER 2012 EASTERN YORK MS WT T SF MS WT T SF MS WT T SF MS WT T SF 21 21 43 1 654321 1 32 111098765 2 3 87654 7 8 131211109 10987654 SCHOOL DISTRICT 18171615141312 1514131211109 20191817161514 17161514131211 25242322212019 22212019181716 27262524232221 1918 23222120 24 2012-2013 3029282726 31 52423 27262 2928 31302928 25 26 292827 30 30 CALENDAR STUDENTS: 5 / 5 STUDENTS: 19 / 24 STUDENTS: 22 / 46 STUDENTS: 17 / 63 TEACHERS: 8 / 8 TEACHERS: 19 / 27 TEACHERS: 22 / 49 TEACHERS: 18 / 67 DECEMBER 2012 JANUARY 2013 FEBRUARY 2013 MARCH 2013 MS WT T SF MS WT T SF MS WT T SF MS WT T SF 1 21 543 21 21 District Priorities 8765432 1211109876 9876543 9876543 1514131211109 19181716151413 1413121110 15 16 16151413121110 22212019181716 20 21 2625242322 17 18 2322212019 2120191817 22 23 STUDENT ENGAGEMENT 23 27262524 28 29 3130292827 2827262524 27262524 28 29 30 30 31 31 CURRICULUM STUDENTS: 15 / 78 STUDENTS: 20 / 98 STUDENTS: 18 / 116 STUDENTS: 18 / 134 TEACHERS: 15 / 82 TEACHERS: 21 / 103 TEACHERS: 18 / 121 TEACHERS: 19 / 140 INSTRUCTION APRIL 2013 MAY 2013 JUNE 2013 ASSESSMENT MS WT T SF MS WT T SF MS WT T SF 1 65432 21 43 1 INTERVENTION 13121110987 111098765 8765432 20191817161514 18171615141312 9 10 1514131211 TECHNOLOGY 27262524232221 2322212019 24 25 22212019181716 302928 26 27 302928 31 2726252423 2928 STAFF DEVELOPMENT 30 STUDENTS: 21 / 155 STUDENTS: 21 / 176 STUDENTS: 5 / 181 TEACHERS: 21 / 161 TEACHERS: 21 / 182 TEACHERS: 6 / 188 EARLY DISMISSALS: 12:45 pm HS/MS, 1:45 pm ELEM ST NO SCHOOL FOR STUDENTS: FEB 15 ............. -

Riverfront Park Feasibility Study

Riverfront Park Feasibility Study Prepared for: Wrightsville Borough, York County, Pennsylvania Study Committee Lori Harmer, Wrightsville Municipal Authority Secretary Janelle Hobbs, Wrightsville Borough Council John Klinedinst, Wrightsville Borough Engineer Mark Lentz, Resident Greg Scritchfield, Wrightsville Borough Council Ed Sipes, Wrightsville Borough Council Ann Walko, York County Planning Commission Teresa Weaver, Eastern School District Melissa Wirls, Wrightsville Borough Secretary Consultants Yost Strodoski Mears, York, PA Recreation and Parks Solutions, Lancaster PA This Project was financed in part by a grant from the Community Conservation Park Partnership Program, Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund, under the administration of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation. December 2011 Riverfront Park Feasibility Study Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Background Information Introduction.................................................................................................................................. 1‐1 Planning Process........................................................................................................................... 1‐1 Riverfront Park ............................................................................................................................. 1‐1 Background and History……………... .............................................................................................. 1‐2 Demographics.............................................................................................................................. -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

F O U Nded 1881 York , Pa

A Record of Cases Argued and Determined in the Various Courts of York County Vol. 132 YORK, PA, THURSDAY, AUGUST 23, 2018 No. 21 CASES REPORTED JAMES M. LANDIS and DONETTA M. LANDIS v. LUTHER H. WILT, deceased, His Successors, Heirs, and Assigns v. ORCHARD GLEN CONDOMINIUM ASSOC. INC., Intervenor NO. 2016-SU-002182-93 Action to Quiet Title – Adverse Possession - Abandonment Page 8 BAR TY ASS UN O O C C IA T K I R O O N Y F O A P U , N K D R ED O 1881 Y Dated Material Do Not Delay Lawyers Concerned for Lawyers York Support Group Meetings 2nd Thursday of each month September 13, 2018 next meeting Strictly confidential program for anyone dealing with alcohol or drug issues, depression, bipolar issues, eating disorders, gambling, etc. For additional information and locations of each – meeting Call LCL 800-‐335-‐2572 or anonymously to Cheryl Kauffman 717-‐854-‐8755 x203 at the York Bar Association All information confidential Size: 2.25w x 4.75h The York Legal Record is published every Thursday by The York County Bar Association. All legal notices must be submitted in typewritten form and are published exactly as submitted by the advertiser. Neither the York Legal Record nor the printer will assume any responsibility to edit, make spelling corrections, eliminate errors in grammar or make any changes in content. Carolyn J. Pugh, Esquire, Editor. The York Legal Record makes no representation as to the quality of services offered by advertiser in this publication. Legal notices must be received by York Legal Record, 137 E. -

Lancaster County Incremental Deliveredhammer a Creekgricultural Lititz Run Lancasterload of Nitro Gcountyen Per HUC12 Middle Creek

PENNSYLVANIA Lancaster County Incremental DeliveredHammer A Creekgricultural Lititz Run LancasterLoad of Nitro gCountyen per HUC12 Middle Creek Priority Watersheds Cocalico Creek/Conestoga River Little Cocalico Creek/Cocalico Creek Millers Run/Little Conestoga Creek Little Muddy Creek Upper Chickies Creek Lower Chickies Creek Muddy Creek Little Chickies Creek Upper Conestoga River Conoy Creek Middle Conestoga River Donegal Creek Headwaters Pequea Creek Hartman Run/Susquehanna River City of Lancaster Muddy Run/Mill Creek Cabin Creek/Susquehanna River Eshlemen Run/Pequea Creek West Branch Little Conestoga Creek/ Little Conestoga Creek Pine Creek Locally Generated Green Branch/Susquehanna River Valley Creek/ East Branch Ag Nitrogen Pollution Octoraro Creek Lower Conestoga River (pounds/acre/year) Climbers Run/Pequea Creek Muddy Run/ 35.00–45.00 East Branch 25.00–34.99 Fishing Creek/Susquehanna River Octoraro Creek Legend 10.00–24.99 West Branch Big Beaver Creek Octoraro Creek 5.00–9.99 Incremental Delivered Load NMap (l Createdbs/a byc rThee /Chesapeakeyr) Bay Foundation Data from USGS SPARROW Model (2011) Conowingo Creek 0.00–4.99 0.00 - 4.99 cida.usgs.gov/sparrow Tweed Creek/Octoraro Creek 5.00 - 9.99 10.00 - 24.99 25.00 - 34.99 35.00 - 45.00 Map Created by The Chesapeake Bay Foundation Data from USGS SPARROW Model (2011) http://cida.usgs.gov/sparrow PENNSYLVANIA York County Incremental Delivered Agricultural YorkLoad Countyof Nitrogen per HUC12 Priority Watersheds Hartman Run/Susquehanna River York City Cabin Creek Green Branch/Susquehanna -

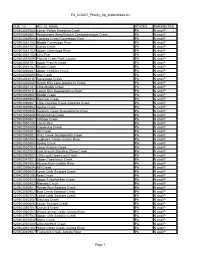

PA COAST Priority Ag Watersheds.Xls

PA_COAST_Priority_Ag_Watersheds.xls HUC_12 HU_12_NAME STATES PARAMETER 020503050505 Lower Yellow Breeches Creek PA N and P 020700040601 Headwaters West Branch Conococheague Creek PA N and P 020503060904 Cocalico Creek-Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061104 Middle Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061701 Conoy Creek PA N and P 020503061103 Upper Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061105 Lititz Run PA N and P 020503051009 Fishing Creek-York County PA N and P 020402030701 Upper French Creek PA N and P 020503061102 Muddy Creek PA N and P 020503060801 Upper Chickies Creek PA N and P 020402030608 Hay Creek PA N and P 020503051010 Conewago Creek PA N and P 020402030606 Green Hills Lake-Allegheny Creek PA N and P 020503061101 Little Muddy Creek PA N and P 020503051011 Laurel Run-Susquehanna River PA N and P 020503060902 Middle Creek PA N and P 020503060903 Hammer Creek PA N and P 020503060901 Little Cocalico Creek-Cocalico Creek PA N and P 020503050904 Spring Creek PA N and P 020503050906 Swatara Creek-Susquehanna River PA N and P 020402030605 Wyomissing Creek PA N and P 020503050801 Killinger Creek PA N and P 020503050105 Laurel Run PA N and P 020402030408 Cacoosing Creek PA N and P 020402030401 Mill Creek PA N and P 020503050802 Snitz Creek-Quittapahilla Creek PA N and P 020503040404 Aughwick Creek-Juniata River PA N and P 020402030406 Spring Creek PA N and P 020402030702 Lower French Creek PA N and P 020503020703 East Branch Standing Stone Creek PA N and P 020503040802 Little Lost Creek-Lost Creek PA N and P 020503041001 Upper Cocolamus Creek -

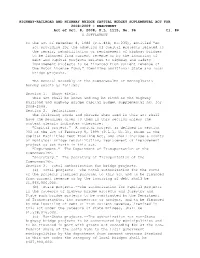

ENACTMENT Act of Oct. 8, 2008, PL 1115

HIGHWAY-RAILROAD AND HIGHWAY BRIDGE CAPITAL BUDGET SUPLEMENTAL ACT FOR 2008-2009 - ENACTMENT Act of Oct. 8, 2008, P.L. 1115, No. 96 Cl. 86 A SUPPLEMENT To the act of December 8, 1982 (P.L.848, No.235), entitled "An act providing for the adoption of capital projects related to the repair, rehabilitation or replacement of highway bridges to be financed from current revenue or by the incurring of debt and capital projects related to highway and safety improvement projects to be financed from current revenue of the Motor License Fund," itemizing additional State and local bridge projects. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania hereby enacts as follows: Section 1. Short title. This act shall be known and may be cited as the Highway- Railroad and Highway Bridge Capital Budget Supplemental Act for 2008-2009. Section 2. Definitions. The following words and phrases when used in this act shall have the meanings given to them in this section unless the context clearly indicates otherwise: "Capital project." A capital project as defined in section 302 of the act of February 9, 1999 (P.L.1, No.1), known as the Capital Facilities Debt Enabling Act, and shall include a county or municipal bridge rehabilitation, replacement or improvement project as set forth in this act. "Department." The Department of Transportation of the Commonwealth. "Secretary." The Secretary of Transportation of the Commonwealth. Section 3. Total authorization for bridge projects. (a) Total projects.--The total authorization for the costs of the projects itemized pursuant to this act and to be financed from current revenue or by the incurring of debt shall be $1,966,906,000. -

Notice Classification of Wild Trout Streams Proposed Additions

Notice Classification of Wild Trout Streams Proposed Additions, Revisions and Removals September 2015 Under 58 Pa. Code §57.11 (relating to listing of wild trout streams), it is the policy of the Fish and Boat Commission (Commission) to accurately identify and classify stream sections supporting naturally reproducing populations of trout as wild trout streams. The Commission’s Fisheries Management Division maintains the list of wild trout streams. The Executive Director, with the approval of the Commission, will from time-to-time publish the list of wild trout streams in the Pennsylvania Bulletin. The listing of a stream section as a wild trout stream is a biological designation that does not determine how it is managed. The Commission relies upon many factors in determining the appropriate management of streams. At the next Commission meeting on September 28 and 29, 2015, the Commission will consider changes to its list of wild trout streams. Specifically, the Commission will consider the addition of the following streams or portions of streams to the list: County of Mouth Mouth Stream Name Section Limits Tributary To Lat/Lon 39.834064 Bedford Tiger Run Headwaters to Mouth Little Wills Creek 78.714294 40.688725 Blair Decker Run Headwaters to Mouth Bald Eagle Creek 78.230606 40.657829 Blair Elk Run Headwaters to Mouth Little Juniata River 78.219475 40.660103 Blair Hutchinson Run Headwaters to Mouth Little Juniata River 78.255722 40.620369 Blair Kelso Run Headwaters to Mouth Bells Gap Run 78.380302 40.637589 Blair Shaw Run Headwaters to -

Susquehanna River Management Plan

SUSQUEHANNA RIVER MANAGEMENT PLAN A management plan focusing on the large river habitats of the West Branch Susquehanna and Susquehanna rivers of Pennsylvania Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission Bureau of Fisheries Division of Fisheries Management 1601 Elmerton Avenue P.O. Box 67000 Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Table of Contents Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... .ii List of Appendix A Tables ...........................................................................................................iii List of Figures .............................................................................................................................v Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... viii Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................ix 1.0 Introduction ....................................................................................................................1 2.0 River Basin Features .......................................................................................................5 3.0 River Characteristics ..................................................................................................... 22 4.0 Special Jurisdictions ..................................................................................................... -

Susquehanna River Basin Commission

Susquehanna River Basin Commission Lower Susquehanna River Publication 288 Subbasin Year-2 October 2013 Focused Watershed Study A Water Quality and Biological Assessment of the Lower Reservoirs of the Susquehanna River Report by Luanne Steffy Aquatic Ecologist SRBC • 4423 N. Front St. • Harrisburg, PA 17110 • 717-238-0423 • 717-238-2436 Fax • www.srbc.net 1 Introduction The Susquehanna River Basin Commission (SRBC) completed a water quality and biological assessment in the lower reservoirs of the Susquehanna River from April-October 2012, as part of the Lower Susquehanna Subbasin Survey Year-2 project (Figure 1). This project was an exploratory pilot study representing the first focused, extensive monitoring effort by SRBC on this portion of the river. The lower reservoirs are located in the final 45 miles of the Susquehanna River before its confluence with the Chesapeake Bay. Three large hydroelectric dam facilities within this reach of river create the three main reservoirs. The objectives of this project were to assess current chemical and biological conditions within the reservoirs while also exploring a variety of assessment methodologies with which to incorporate routine monitoring of the reservoirs into SRBC’s on-going monitoring program. The Subbasin Survey Program is one of SRBC’s longest standing monitoring programs, ongoing since the mid-1980s, and is funded by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). This program consists of two-year assessments in each of the six major subbasins of the Susquehanna River Basin Figure 1. Location of the Lower Reservoir Section of the on a rotating basis. The Year-1 studies involve broad-brush, one- Susquehanna River within the Susquehanna River Basin time sampling efforts of about 100 stream sites to assess water quality, macroinvertebrate communities, and physical habitat three reservoirs serve as drinking water supplies and are also throughout an entire subbasin.