The Postwar Suburbanization of American Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1986 Comprehensive Plan

THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN FOR FAIRFAX COUNTY, VIRGINIA This document consists of the Area i Plan, adopted June 16,1975, and all amend ments adopted through October 27, 1986. Any subsequent amendments are available from Maps and Publications Sales, Massey Building, Fairfax, Virginia 691-2974. The Board of Supervisors has established a regular Annual Plan Review and updating process to insure the continuing relevance of the Pian. For informa tion regarding the Annual Plan Review, please call 691-2641. This document, which is to be used in conjunction with the Area Plan maps, provides background information and planning policy guidelines for Fairfax County, as required by the Code of Virginia, as amended. 1986 EDITION (As Amended Through October 27th, 1986) Fairfax County Comprehensive Plan, 1986 Edition, Area I BOARD OF SUPERVISORS John F. Herrity, Chairman Mrs. Martha V. Pennino, Centreville District Vice Chairman Joseph Alexander, Lee District Nancy K. Falck, Dranesville District Thomas M. Davis, Mason District Katherine K. Hanley, Providence District T. Farrell Egge, Mount Vernon District Elaine McConnell, Springfield District Audrey Moore, Annandale District J. Hamilton Lambert, County Executive Denton U. Kent, Deputy County Executive for Planning and Development PLANNING COMMISSION George M. Lilly, Dranesville District Chairman John R. Byers, Mt. Vernon District Peter F. Murphy, Jr., Springfield District Patrick M. Hanlon, Providence District Carl L. Sell, Jr., Lee District Suzanne F. Harsel, Annandale District Robert R. Sparks, Jr., Mason District Ronald W. Koch, At-Large John H. Thillmann, Centreville District William M. Lockwood, At-Large Alvin L. Thomas, At-Large James C. Wyckoff, Jr., Executive Director OFFICE OF COMPREHENSIVE PLANNING James P. -

Creating a Pedestrian Friendly Tysons Corner

CREATING A PEDESTRIAN FRIENDLY TYSONS CORNER By RYAN WING A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2010 1 © 2010 Ryan Wing 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my chair, Joseli Macedo, and cochair, Richard Schneider, for their time, encouragement and recommendations to help this become a better, more complete document. Just when you think everything is done and you have a completed thesis, they come back to tell you more that they want to see and ways to improve it. I would like to thank my parents for their constant encouragement and support. Throughout the research and writing process they were always urging me along with kind and motivating words. They would be the constant reminder that, despite having seven years to finish the thesis once the program is started, that I was not allowed to take that long. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 3 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 6 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 10 2 REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ........................................................................... -

Stouffer's Starts Running Morss Hall Food Service

NEWSPAPEROF THE UNDERGRADUATES OF THE ASSACHUSETTS INSTITUE OF TECHNLOGY OFFICIAL .. NWSPPEROF THE UNDERGRADUATES OF THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OL. LXKVII NOo. I CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS, FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 1957 5 CENT i r i -4 -- , - I -- , ry Library Guards Stouffer's Starts Running o Curb Book Thefts aut Chief Woe Is $s Morss Hall Food Service "I honestly don't lknow of any food- about the deterioration of Commons "We are the last major urban in- meals, Mr. Maclaurin said that about itution to initiate such a plan," service company which serves as good food at such low prices." In this way, the only appreciable change made tes Professor W. N. Locke, Direc- was in limiting the number of bev- r of the Institute Libraries, of the R. Colin Maclaurin, Director of Gen- eral Services, describes Stouffer's, elages served on Commons to one in- ew library "Book checking" policy. stead of three, as previously. This -ting. the inconvenience to Institute the firm which will manage the din- ing service in Morss Hall and Pritch- and the other minor changes in the udents and faculty of the some five food were necessary in view of the ousand odd dollars of "missing" et Lounge this term. In a few weeks, Stouffer's recipes rising costs of food and labor within oks which plague the system annu- the last few years. For example, the ly, Locke emphasized the "frustrat- will be used to prepare the food serv- ed in Walker Memorial, and the firm salaries of the employees were re- g" nature of book disappearances cently raised by 10%. -

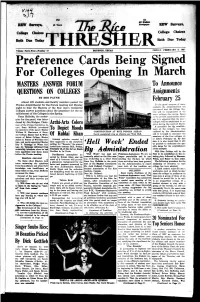

Preference Cards Being Signed for Colleges Opening in March

*44 oito All StwMat . REW Surreys, 40 YMMI Newspaper REW Surveys, College Choices College Choices Both Due Today Both Due Today Volume Forty«Four—Number 17 HOUSTON, TEXAS FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 1957 Preference Cards Being Signed For Colleges Opening In March MASTERS ANSWER FORUM To Announce QUESTIONS ON COLLEGES Assignments BY DON PAYNE February 25 Almost 400 students and faculty members packed the Physics Amphitheater for the Forum meeting last Monday To the greac surprise of many night-to hear the Masters of the four men's residential students the Administration haa announced that the College Sys- Colleges answer questions about the procedure for the es- tem will be inaugurated in the tablishment of the Colleges in the Spring. men's colleges this spring. Based Dean McBride, the moder- on the present construction sched- ator for the panel, was intro- ule, it is expected that the men's duced by Jim Hedges, Chair- colleges will be established in ro- man of the Forum Committee. In Archi-Arts Colors tation during the month of March, turn Dean McBride introduced A procedure for tfrg establish- the members of the panel: Master To Depict Moods ment of the colleges has been William H. Masterson of Hans- CONSTRUCTION AT RICE FORGES AHEAD outlined by the Administration, zejn College, Master Carl R. Wish- Newly completed wing on what is now West Hall. and it is hoped to announce the meyer of Baker College, Master Of Kublai Khan members of the four colleges on James S. Fulton of Will Rice Col- Oriental splendor created by 9 or before February 25. -

Einstein, History, and Other Passions : the Rebellion Against Science at the End of the Twentieth Century

Einstein, history, and other passions : the rebellion against science at the end of the twentieth century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Holton, Gerald James. 2000. Einstein, history, and other passions : the rebellion against science at the end of the twentieth century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Published Version http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674004337 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:23975375 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA EINSTEIN, HISTORY, ANDOTHER PASSIONS ;/S*6 ? ? / ? L EINSTEIN, HISTORY, ANDOTHER PASSIONS E?3^ 0/" Cf72fM?y GERALD HOLTON A HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS C%772^r?<%gf, AizziMc^zzyeZZy LozzJozz, E?zg/%??J Q AOOO Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in capital letters. PHYSICS RESEARCH LIBRARY NOV 0 4 1008 Copyright @ 1996 by Gerald Holton All rights reserved HARVARD UNIVERSITY Printed in the United States of America An earlier version of this book was published by the American Institute of Physics Press in 1995. First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2000 o/ CoMgre.w C%t%/og;Hg-zM-PMMt'%tz'c7t Dzztzz Holton, Gerald James. -

Mathematics of the Gateway Arch Page 220

ISSN 0002-9920 Notices of the American Mathematical Society ABCD springer.com Highlights in Springer’s eBook of the American Mathematical Society Collection February 2010 Volume 57, Number 2 An Invitation to Cauchy-Riemann NEW 4TH NEW NEW EDITION and Sub-Riemannian Geometries 2010. XIX, 294 p. 25 illus. 4th ed. 2010. VIII, 274 p. 250 2010. XII, 475 p. 79 illus., 76 in 2010. XII, 376 p. 8 illus. (Copernicus) Dustjacket illus., 6 in color. Hardcover color. (Undergraduate Texts in (Problem Books in Mathematics) page 208 ISBN 978-1-84882-538-3 ISBN 978-3-642-00855-9 Mathematics) Hardcover Hardcover $27.50 $49.95 ISBN 978-1-4419-1620-4 ISBN 978-0-387-87861-4 $69.95 $69.95 Mathematics of the Gateway Arch page 220 Model Theory and Complex Geometry 2ND page 230 JOURNAL JOURNAL EDITION NEW 2nd ed. 1993. Corr. 3rd printing 2010. XVIII, 326 p. 49 illus. ISSN 1139-1138 (print version) ISSN 0019-5588 (print version) St. Paul Meeting 2010. XVI, 528 p. (Springer Series (Universitext) Softcover ISSN 1988-2807 (electronic Journal No. 13226 in Computational Mathematics, ISBN 978-0-387-09638-4 version) page 315 Volume 8) Softcover $59.95 Journal No. 13163 ISBN 978-3-642-05163-0 Volume 57, Number 2, Pages 201–328, February 2010 $79.95 Albuquerque Meeting page 318 For access check with your librarian Easy Ways to Order for the Americas Write: Springer Order Department, PO Box 2485, Secaucus, NJ 07096-2485, USA Call: (toll free) 1-800-SPRINGER Fax: 1-201-348-4505 Email: [email protected] or for outside the Americas Write: Springer Customer Service Center GmbH, Haberstrasse 7, 69126 Heidelberg, Germany Call: +49 (0) 6221-345-4301 Fax : +49 (0) 6221-345-4229 Email: [email protected] Prices are subject to change without notice. -

A History of the Department of Defense Federally Funded Research and Development Centers

A History of the Department of Defense Federally Funded Research and Development Centers June 1995 OTA-BP-ISS-157 GPO stock #052-003-01420-3 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, A History of the Department of Defense Federally Funded Research and Development Centers, OTA-BP-ISS-157 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, June 1995). oreword he 104th Congress, like its recent predecessors, is grappling with the role of modeling and simulation in defense planning, acquisition, and training, a role that current and contemplated technological develop- ments will intensify. The Department of Defense (DoD) Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs), some closely tied to defense modeling and simulation, are also a topic of recurrent congressional concern owing to their unique institutional status. The 104th’s emphasis on pri- vate sector solutions suggests that this Congress in particular will seek to ad- dress the FFRDCs. This Office of Technology Assessment Background Paper has been prepared to help Congress do so. The DoD FFRDCs trace their lineage to ad hoc, not-for-profit, university- based organizations created during World War II to address specific technolog- ical problems. Some performed studies and analyses on topics such as anti- submarine warfare, but the majority were laboratories engaged in the development of radar, the proximity fuze, and other war-winning weapons in- cluding nuclear weapons. These centers proved useful in bridging the orga- nizational, compensation-related, and cultural gaps between science and the military, and more were created during the Cold War. The laboratories contin- ued to predominate in some respects, but centers devoted to study and analysis grew and entered the public consciousness as “think tanks,” and other centers embarked upon a new role—system integration. -

Anser-50Th-History-Book.Pdf

ANALYTIC SERVICES INC. ANALYTIC SERVICES INC. Celebrating 50 Years a H i s t o r Y o f a n a lY t i C s e r v i C e s i n C . YEARS YEARS 1 9 5 8 - 2 0 0 8 1 9 5 8 - 2 0 0 8 PUBLIC SERVICE. PUBLIC TRUST. PUBLIC SERVICE. PUBLIC TRUST. Written By David Bounds The author thanks Tom Benjamin, Joan Zaorski, Mary Webb, Allifa Settles-Mitchell, Cathy Lee, Jack Butler, Mike Bowers, and Paul Higgins for their great assistance in bringing this project to fruition. Thanks as well to Harry Emlet, George Thompson, Steve Hopkins, Trina Powell, Christina Scott, and many other Analytic Services Inc. staff—past and present—who gave time, insight, and memories to this. As you will see on the next page… this was all about you. [ ii ] [ 111 ] ANALYTIC SERVICES INC. A History of An A ly t i c s e r v i c e s i n c . YEARS 1 9 5 8 - 2 0 0 8 PUBLIC SERVICE. PUBLIC TRUST. Dedicated to—in the words of the senior leadership over the life of the corporation so far—the “people, people, people” of Analytic Services Inc., for their efforts that have made this corporation, for their efforts that have helped make this Nation. [ iii ] ANALYTIC SERVICES INC. c e l e b r A t i n g 5 0 y e A r s YEARS 1 9 5 8 - 2 0 0 8 PUBLIC SERVICE. PUBLIC TRUST. [ iv ] ANALLYTICIC SERVIICES INC. -

Joseph Sweetman Ames 1864-1943

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XXIII SEVENTH MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF JOSEPH SWEETMAN AMES 1864-1943 BY HENRY CREW PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1944 JOSEPH SWEETMAN AMES 1864-1943 BY HENRY CREW There are times when a single act characterizes the entire life of a man. Such an occasion was the publication of his first scientific paper by Joseph S. Ames. He had just taken his bachelor's degree at Johns Hopkins University; was an assistant in the laboratory and was, at the same time, working toward a doctor's degree. On his way to those experimental results which later formed his doctor's dissertation, he had met for the first time the then recently invented concave grating. This remark- able instrument he mastered, in theory and in practice, so com- pletely that he was invited by its inventor to describe, for the leading journal of physics, its construction, adjustment and use. This he did with such accuracy, clarity and completeness that this first paper soon became and remained, on both sides of the Atlantic, the standard guide for the Rowland mounting. The outstanding features of this paper (Phil. Mag. 2j, 369, 1889) are simplicity, logical sequence, accuracy, fine perspective; and these are also the outstanding features of Ames' life. Two great English poets have taught us that the child is father to the man; a dictum which every man who has lived through two generations has verified for himself. It is there- fore well worthwhile to follow the rather meagre record of this man's ancestry in order to discover, if possible, among his fore- bears and friends—for these latter are often one's most im- portant ancestors—the origin of some of those qualities so highly cherished by men who knew him. -

Against Method (AM for Short)

First published by New Left Books, 1975 Revised edition published by Verso 1988 Third edition published by Verso 1993 © Paul Feyerabend 1975, 1988, 1993 All rights reserved Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London WIV 3HR USA: 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001-2291 Verso is the imprint of New Left Books British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data available ISBN 0-86091-48 1-X ISBN 0-8609 1 -646-4 US Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data available Typeset by Keyboard Services, Luton Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddies Ltd, Guildford and King's Lynn Contents Preface vii Preface to the Third Edition IX Introductionto the Chinese Edition 1 Analytical Index 5 Introduction 9 Parts1-20 14 Postscript on Relativism 268 Index 273 Preface In 1970 Imre Lakatos, one of the best friends I ever had, corneredme at a party. 'Paul,' he said, 'you have such strange ideas. Why don't you write them down? I shall write a reply, we publish the whole thing and I promise you - we shall have lots of fun.' I liked the suggestion and started working. The manuscript of my part of the book was finished in 1972 and I sent it to London. There it disappeared under rather mysterious circumstances. lmre Lakatos, who loved dramatic gestures, notified Interpol and, indeed, Interpol found my manu script and returned it to me. I reread it and made some final changes. In February 1974, only a few weeks after I had finished my revision, I was informed of Imre's death. -

History Newsletter CENTER for HISTORY of PHYSICS&NIELS BOHR LIBRARY & ARCHIVES Vol

History Newsletter CENTER FOR HISTORY OF PHYSICS&NIELS BOHR LIBRARY & ARCHIVES Vol. 45, No. 2 • Winter 2013–2014 1,000+ Oral History Interviews Now Online Since June 2007, the Niels Bohr Library societies. Some of the interviews were Through this hard work, we have been & Archives (NBL&A) has been working conducted by staff of the Center for able to receive updated permissions to place its widely used oral history History of Physics (CHP) and many were and often hear from families that did interview collection online for its acquired from individual scholars who not know an interview existed and are researchers to easily access. With the were often helped by our Grant-in-Aid pleased to know that their relative’s work help of two National Endowment for the program. These interviews help tell will be remembered and available to Humanities (NEH) grants, we are proud the personal stories of these famous anyone interested. to announce that we have now placed over two- With the completion of thirds of our collection the grants, we have just online (http://www.aip.org/ over 1,025 of our over history/ohilist/transcripts. 1,500 transcripts online. html ). These transcripts include abstracts of the interview, The oral histories at photographs from ESVA NBL&A are one of our when available, and links most used collections, to the interview’s catalog second only to the record in our International photographs in the Emilio Catalog of Sources (ICOS). Segrè Visual Archives We have short audio clips (ESVA). They cover selected by our post- topics such as quantum doctoral historian of 75 physics, nuclear physics, physicists in a range of astronomy, cosmology, solid state physicists and allow the reader insight topics showing some of the interesting physics, lasers, geophysics, industrial into their lives, works, and personalities. -

1Iiiiiiiln~~Nm~Li 1111

[Reprinted from SCIENCE, N. 8., J'oZ. XL V., No. 1160, Pages 284-286, Maroh f8, 1917J AN INSTITUTE FOR THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND CIVILIZATION To those interested in placing before Ameri can students 'advantages not only greater than are now ofIered in this country, but greater than those ofIe:red abroad, the following state ment may suggest an opportunity. The history of science deals with so large a part of the intellectual development of the race, that it should attract the interest of every thinking person. Such an interest is already manifest among an ever-increasing number oi scientists and technicians. Furthermore, a very general interest is 'also becoming appar ent, for example, in the history of the numer ous means of locomotion from the mst beasts of burden to the airplane of to-day; in the his tory of computation from the ingenious but rude abacus to the refined calculating machine; in the history of such methods of communica tion as telegraphy and telephony and in the history of medical and surgical practise. If we consider it from 'a higher point of view, the importance of the hi'story of science 00- 1111 1IIIIiiiln~~nm~li129807 2 comes even greater. We then realize that sci ence is the strongest force that makes for the unity of our civilization, that it is also essen tiaIly a cumulative process, and hence that no history of civilization can be tolerably true and complete in which the development of science is not given a considerable place. lndeed, the evolution of science must be the leading thread of aU general history.