Lecture 12 Quantum Mechanics and Atomic Orbitals Bohr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atomic Orbitals

Visualization of Atomic Orbitals Source: Robert R. Gotwals, Jr., Department of Chemistry, North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, Durham, NC, 27705. Email: [email protected]. Copyright ©2007, all rights reserved, permission to use for non-commercial educational purposes is granted. Introductory Readings Where are the electrons in an atom? There are a number of Models - a description of models that look to describe the location and behavior of some physical object or electrons in atoms. It is important to know this information, as behavior in nature. Models it helps chemists to make statements and predictions about are often mathematical, describing the behavior of how atoms will react with other atoms to form molecules. The some event. model one chooses will oftentimes influence the types of statements one can make about the behavior – that is, the reactivity – of an atom or group of atoms. Bohr model - states that no One model, the Bohr model, describes electrons as small two electrons in an atom can billiard balls, rotating around the positively charged nucleus, have the same set of four much in the way that planets quantum numbers. orbit around the Sun. The placement and motion of electrons are found in fixed and quantifiable levels called orbits, Orbits- where electrons are or, in older terminology, shells. believed to be located in the There are specific numbers of Bohr model. Orbits have a electrons that can be found in fixed amount of energy, and are identified with the each orbit – 2 for the first orbit, principle quantum number 8 for the second, and so forth. -

Unit 1 Old Quantum Theory

UNIT 1 OLD QUANTUM THEORY Structure Introduction Objectives li;,:overy of Sub-atomic Particles Earlier Atom Models Light as clectromagnetic Wave Failures of Classical Physics Black Body Radiation '1 Heat Capacity Variation Photoelectric Effect Atomic Spectra Planck's Quantum Theory, Black Body ~diation. and Heat Capacity Variation Einstein's Theory of Photoelectric Effect Bohr Atom Model Calculation of Radius of Orbits Energy of an Electron in an Orbit Atomic Spectra and Bohr's Theory Critical Analysis of Bohr's Theory Refinements in the Atomic Spectra The61-y Summary Terminal Questions Answers 1.1 INTRODUCTION The ideas of classical mechanics developed by Galileo, Kepler and Newton, when applied to atomic and molecular systems were found to be inadequate. Need was felt for a theory to describe, correlate and predict the behaviour of the sub-atomic particles. The quantum theory, proposed by Max Planck and applied by Einstein and Bohr to explain different aspects of behaviour of matter, is an important milestone in the formulation of the modern concept of atom. In this unit, we will study how black body radiation, heat capacity variation, photoelectric effect and atomic spectra of hydrogen can be explained on the basis of theories proposed by Max Planck, Einstein and Bohr. They based their theories on the postulate that all interactions between matter and radiation occur in terms of definite packets of energy, known as quanta. Their ideas, when extended further, led to the evolution of wave mechanics, which shows the dual nature of matter -

Quantum Theory of the Hydrogen Atom

Quantum Theory of the Hydrogen Atom Chemistry 35 Fall 2000 Balmer and the Hydrogen Spectrum n 1885: Johann Balmer, a Swiss schoolteacher, empirically deduced a formula which predicted the wavelengths of emission for Hydrogen: l (in Å) = 3645.6 x n2 for n = 3, 4, 5, 6 n2 -4 •Predicts the wavelengths of the 4 visible emission lines from Hydrogen (which are called the Balmer Series) •Implies that there is some underlying order in the atom that results in this deceptively simple equation. 2 1 The Bohr Atom n 1913: Niels Bohr uses quantum theory to explain the origin of the line spectrum of hydrogen 1. The electron in a hydrogen atom can exist only in discrete orbits 2. The orbits are circular paths about the nucleus at varying radii 3. Each orbit corresponds to a particular energy 4. Orbit energies increase with increasing radii 5. The lowest energy orbit is called the ground state 6. After absorbing energy, the e- jumps to a higher energy orbit (an excited state) 7. When the e- drops down to a lower energy orbit, the energy lost can be given off as a quantum of light 8. The energy of the photon emitted is equal to the difference in energies of the two orbits involved 3 Mohr Bohr n Mathematically, Bohr equated the two forces acting on the orbiting electron: coulombic attraction = centrifugal accelleration 2 2 2 -(Z/4peo)(e /r ) = m(v /r) n Rearranging and making the wild assumption: mvr = n(h/2p) n e- angular momentum can only have certain quantified values in whole multiples of h/2p 4 2 Hydrogen Energy Levels n Based on this model, Bohr arrived at a simple equation to calculate the electron energy levels in hydrogen: 2 En = -RH(1/n ) for n = 1, 2, 3, 4, . -

October 16, 2014

October 16, 2014 Chapter 5: Electrons in Atoms Honors Chemistry Bohr Model Niels Bohr, a young Danish physicist and a student of Rutherford improved Rutherford's model. Bohr proposed that an electron is found only in specific circular paths, or orbits, around the nucleus. Each electron orbit has a fixed energy. Energy levels: the fixed energies of an electron. Quantum: The amount of energy required to move an electron from one energy level to another level. Light Electrons can jump from one energy level to another. The term quantum leap can be used to describe an The modern quantum model grew out of the study of light. 1. Light as a wave abrupt change in energy. 2. Light as a particle -Newton was the first to try to explain the behavior of light by assuming that light consists of particles. October 16, 2014 Light as a Wave 1. Wavelength-shortest distance between equivalent points on a continuous wave. symbol: λ (Greek letter lambda) 2. Frequency- the number of waves that pass a point per second. symbol: ν (Greek letter nu) 3. Amplitude-wave's height from the origin to the crest or trough. 4. Speed-all EM waves travel at the speed of light. symbol: c=3.00 x 108 m/s in a vacuum The speed of light Calculate the following: 8 1. The wavelength of radiation with a frequency of 1.50 x 1013 c=3.00 x 10 m/s Hz. Does this radiation have a longer or shorter wavelength than red light? (2.00 x 10-5 m; longer than red) c=λν 2. -

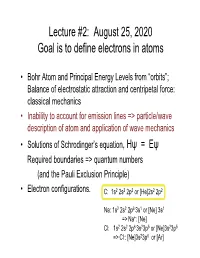

Lecture #2: August 25, 2020 Goal Is to Define Electrons in Atoms

Lecture #2: August 25, 2020 Goal is to define electrons in atoms • Bohr Atom and Principal Energy Levels from “orbits”; Balance of electrostatic attraction and centripetal force: classical mechanics • Inability to account for emission lines => particle/wave description of atom and application of wave mechanics • Solutions of Schrodinger’s equation, Hψ = Eψ Required boundaries => quantum numbers (and the Pauli Exclusion Principle) • Electron configurations. C: 1s2 2s2 2p2 or [He]2s2 2p2 Na: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s1 or [Ne] 3s1 => Na+: [Ne] Cl: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s23p5 or [Ne]3s23p5 => Cl-: [Ne]3s23p6 or [Ar] What you already know: Quantum Numbers: n, l, ml , ms n is the principal quantum number, indicates the size of the orbital, has all positive integer values of 1 to ∞(infinity) (Bohr’s discrete orbits) l (angular momentum) orbital 0s l is the angular momentum quantum number, 1p represents the shape of the orbital, has integer values of (n – 1) to 0 2d 3f ml is the magnetic quantum number, represents the spatial direction of the orbital, can have integer values of -l to 0 to l Other terms: electron configuration, noble gas configuration, valence shell ms is the spin quantum number, has little physical meaning, can have values of either +1/2 or -1/2 Pauli Exclusion principle: no two electrons can have all four of the same quantum numbers in the same atom (Every electron has a unique set.) Hund’s Rule: when electrons are placed in a set of degenerate orbitals, the ground state has as many electrons as possible in different orbitals, and with parallel spin. -

Principal, Azimuthal and Magnetic Quantum Numbers and the Magnitude of Their Values

268 A Textbook of Physical Chemistry – Volume I Principal, Azimuthal and Magnetic Quantum Numbers and the Magnitude of Their Values The Schrodinger wave equation for hydrogen and hydrogen-like species in the polar coordinates can be written as: 1 휕 휕휓 1 휕 휕휓 1 휕2휓 8휋2휇 푍푒2 (406) [ (푟2 ) + (푆푖푛휃 ) + ] + (퐸 + ) 휓 = 0 푟2 휕푟 휕푟 푆푖푛휃 휕휃 휕휃 푆푖푛2휃 휕휙2 ℎ2 푟 After separating the variables present in the equation given above, the solution of the differential equation was found to be 휓푛,푙,푚(푟, 휃, 휙) = 푅푛,푙. 훩푙,푚. 훷푚 (407) 2푍푟 푘 (408) 3 푙 푘=푛−푙−1 (−1)푘+1[(푛 + 푙)!]2 ( ) 2푍 (푛 − 푙 − 1)! 푍푟 2푍푟 푛푎 √ 0 = ( ) [ 3] . exp (− ) . ( ) . ∑ 푛푎0 2푛{(푛 + 푙)!} 푛푎0 푛푎0 (푛 − 푙 − 1 − 푘)! (2푙 + 1 + 푘)! 푘! 푘=0 (2푙 + 1)(푙 − 푚)! 1 × √ . 푃푚(퐶표푠 휃) × √ 푒푖푚휙 2(푙 + 푚)! 푙 2휋 It is obvious that the solution of equation (406) contains three discrete (n, l, m) and three continuous (r, θ, ϕ) variables. In order to be a well-behaved function, there are some conditions over the values of discrete variables that must be followed i.e. boundary conditions. Therefore, we can conclude that principal (n), azimuthal (l) and magnetic (m) quantum numbers are obtained as a solution of the Schrodinger wave equation for hydrogen atom; and these quantum numbers are used to define various quantum mechanical states. In this section, we will discuss the properties and significance of all these three quantum numbers one by one. Principal Quantum Number The principal quantum number is denoted by the symbol n; and can have value 1, 2, 3, 4, 5…..∞. -

Vibrational Quantum Number

Fundamentals in Biophotonics Quantum nature of atoms, molecules – matter Aleksandra Radenovic [email protected] EPFL – Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne Bioengineering Institute IBI 26. 03. 2018. Quantum numbers •The four quantum numbers-are discrete sets of integers or half- integers. –n: Principal quantum number-The first describes the electron shell, or energy level, of an atom –ℓ : Orbital angular momentum quantum number-as the angular quantum number or orbital quantum number) describes the subshell, and gives the magnitude of the orbital angular momentum through the relation Ll2 ( 1) –mℓ:Magnetic (azimuthal) quantum number (refers, to the direction of the angular momentum vector. The magnetic quantum number m does not affect the electron's energy, but it does affect the probability cloud)- magnetic quantum number determines the energy shift of an atomic orbital due to an external magnetic field-Zeeman effect -s spin- intrinsic angular momentum Spin "up" and "down" allows two electrons for each set of spatial quantum numbers. The restrictions for the quantum numbers: – n = 1, 2, 3, 4, . – ℓ = 0, 1, 2, 3, . , n − 1 – mℓ = − ℓ, − ℓ + 1, . , 0, 1, . , ℓ − 1, ℓ – –Equivalently: n > 0 The energy levels are: ℓ < n |m | ≤ ℓ ℓ E E 0 n n2 Stern-Gerlach experiment If the particles were classical spinning objects, one would expect the distribution of their spin angular momentum vectors to be random and continuous. Each particle would be deflected by a different amount, producing some density distribution on the detector screen. Instead, the particles passing through the Stern–Gerlach apparatus are deflected either up or down by a specific amount. -

Performance of Numerical Approximation on the Calculation of Two-Center Two-Electron Integrals Over Non-Integer Slater-Type Orbitals Using Elliptical Coordinates

Performance of numerical approximation on the calculation of two-center two-electron integrals over non-integer Slater-type orbitals using elliptical coordinates A. Bağcı* and P. E. Hoggan Institute Pascal, UMR 6602 CNRS, University Blaise Pascal, 24 avenue des Landais BP 80026, 63177 Aubiere Cedex, France [email protected] Abstract The two-center two-electron Coulomb and hybrid integrals arising in relativistic and non- relativistic ab-initio calculations of molecules are evaluated over the non-integer Slater-type orbitals via ellipsoidal coordinates. These integrals are expressed through new molecular auxiliary functions and calculated with numerical Global-adaptive method according to parameters of non-integer Slater- type orbitals. The convergence properties of new molecular auxiliary functions are investigated and the results obtained are compared with results found in the literature. The comparison for two-center two- electron integrals is made with results obtained from one-center expansions by translation of wave- function to same center with integer principal quantum number and results obtained from the Cuba numerical integration algorithm, respectively. The procedures discussed in this work are capable of yielding highly accurate two-center two-electron integrals for all ranges of orbital parameters. Keywords: Non-integer principal quantum numbers; Two-center two-electron integrals; Auxiliary functions; Global-adaptive method *Correspondence should be addressed to A. Bağcı; e-mail: [email protected] 1 1. Introduction The idea of considering the principal quantum numbers over Slater-type orbitals (STOs) in the set of positive real numbers firstly introduced by Parr [1] and performed for the He atom and single- center calculations on the H2 molecule to demonstrate that improved accuracy can be achieved in Hartree-Fock-Roothaan (HFR) calculations. -

Further Quantum Physics

Further Quantum Physics Concepts in quantum physics and the structure of hydrogen and helium atoms Prof Andrew Steane January 18, 2005 2 Contents 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Quantum physics and atoms . 7 1.1.1 The role of classical and quantum mechanics . 9 1.2 Atomic physics—some preliminaries . .... 9 1.2.1 Textbooks...................................... 10 2 The 1-dimensional projectile: an example for revision 11 2.1 Classicaltreatment................................. ..... 11 2.2 Quantum treatment . 13 2.2.1 Mainfeatures..................................... 13 2.2.2 Precise quantum analysis . 13 3 Hydrogen 17 3.1 Some semi-classical estimates . 17 3.2 2-body system: reduced mass . 18 3.2.1 Reduced mass in quantum 2-body problem . 19 3.3 Solution of Schr¨odinger equation for hydrogen . ..... 20 3.3.1 General features of the radial solution . 21 3.3.2 Precisesolution.................................. 21 3.3.3 Meanradius...................................... 25 3.3.4 How to remember hydrogen . 25 3.3.5 Mainpoints.................................... 25 3.3.6 Appendix on series solution of hydrogen equation, off syllabus . 26 3 4 CONTENTS 4 Hydrogen-like systems and spectra 27 4.1 Hydrogen-like systems . 27 4.2 Spectroscopy ........................................ 29 4.2.1 Main points for use of grating spectrograph . ...... 29 4.2.2 Resolution...................................... 30 4.2.3 Usefulness of both emission and absorption methods . 30 4.3 The spectrum for hydrogen . 31 5 Introduction to fine structure and spin 33 5.1 Experimental observation of fine structure . ..... 33 5.2 TheDiracresult ..................................... 34 5.3 Schr¨odinger method to account for fine structure . 35 5.4 Physical nature of orbital and spin angular momenta . -

Chapter 8 2013

described by Core Chapter 8 Electrons Wave Function e- filling spdf electronic configuration comprising (Orbital) Valence determined by Electrons described by Aufbau basis for Rules Periodic Quantum which involve Table Numbers which summarizes Orbital Pauli Hund’s which are Energy Exclusion Rule Periodic Properties Electron Configuration and Chemical Periodicity Quantum 4-quantum numbers specify the energy and location of Numbers electrons around a nucleus (all we can know). This numbers are the framework for the “electronic structure Orbital size of an atom”. Principal define & energy n = 1,2,3,.. s defines Name Symbol Permitted Values Property principal n positive integers (1,2,3...) orbital energy (size) Angular Orbital angular l orbital shape (0, 1, 2, and 3 momentum, l defines momentum integers from 0 to n-1 correspond to s, p, d, and f shape orbitals, respectively.) Magnetic Orbital magnetic integers from -l to 0 to +l orbital orientation in space defines ml ml orientation direction of e- spin spin m +1/2 or -1/2 Electron s Spin, ms defines spin Quantum Allowed Schrodinger’s equation gives an exact solution for H- Possible Orbitals Number Values atom, but does not for many electron-atoms. Electron- n Positive integers 1 2 3 electron repulsion in multi-electron split energy levels. 1,2,3,4.... Hydrogen Atom Multi-electron atoms 0 0 1 0 1 2 l 0 up to max Orbitals are of n-1 “degenerate” or Energy the same energy in Hydrogen! ml -l,...0...+l 0 0 -1 0 1 0 -1 0 1 -2-1 0 12 Orbital Name 1s 2s 2p 3s 3p 3d Electrons will Shapes or Boundry fill lowest Surface Plots energy orbitals first! Inner core electrons “shield” or “screen” outer 4-quantum numbers specify all the information we can know the energy electrons from the positive charge of the nucleus. -

Quantum Mechanics C (Physics 130C) Winter 2015 Assignment 2

University of California at San Diego { Department of Physics { Prof. John McGreevy Quantum Mechanics C (Physics 130C) Winter 2015 Assignment 2 Posted January 14, 2015 Due 11am Thursday, January 22, 2015 Please remember to put your name at the top of your homework. Go look at the Physics 130C web site; there might be something new and interesting there. Reading: Preskill's Quantum Information Notes, Chapter 2.1, 2.2. 1. More linear algebra exercises. (a) Show that an operator with matrix representation 1 1 1 P = 2 1 1 is a projector. (b) Show that a projector with no kernel is the identity operator. 2. Complete sets of commuting operators. In the orthonormal basis fjnign=1;2;3, the Hermitian operators A^ and B^ are represented by the matrices A and B: 0a 0 0 1 0 0 ib 01 A = @0 a 0 A ;B = @−ib 0 0A ; 0 0 −a 0 0 b with a; b real. (a) Determine the eigenvalues of B^. Indicate whether its spectrum is degenerate or not. (b) Check that A and B commute. Use this to show that A^ and B^ do so also. (c) Find an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors common to A and B (and thus to A^ and B^) and specify the eigenvalues for each eigenvector. (d) Which of the following six sets form a complete set of commuting operators for this Hilbert space? (Recall that a complete set of commuting operators allow us to specify an orthonormal basis by their eigenvalues.) fA^g; fB^g; fA;^ B^g; fA^2; B^g; fA;^ B^2g; fA^2; B^2g: 1 3.A positive operator is one whose eigenvalues are all positive. -

![On the Symmetry of the Quantum-Mechanical Particle in a Cubic Box Arxiv:1310.5136 [Quant-Ph] [9] Hern´Andez-Castillo a O and Lemus R 2013 J](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3436/on-the-symmetry-of-the-quantum-mechanical-particle-in-a-cubic-box-arxiv-1310-5136-quant-ph-9-hern%C2%B4andez-castillo-a-o-and-lemus-r-2013-j-563436.webp)

On the Symmetry of the Quantum-Mechanical Particle in a Cubic Box Arxiv:1310.5136 [Quant-Ph] [9] Hern´Andez-Castillo a O and Lemus R 2013 J

On the symmetry of the quantum-mechanical particle in a cubic box Francisco M. Fern´andez INIFTA (UNLP, CCT La Plata-CONICET), Blvd. 113 y 64 S/N, Sucursal 4, Casilla de Correo 16, 1900 La Plata, Argentina E-mail: [email protected] arXiv:1310.5136v2 [quant-ph] 25 Dec 2014 Particle in a cubic box 2 Abstract. In this paper we show that the point-group (geometrical) symmetry is insufficient to account for the degeneracy of the energy levels of the particle in a cubic box. The discrepancy is due to hidden (dynamical symmetry). We obtain the operators that commute with the Hamiltonian one and connect eigenfunctions of different symmetries. We also show that the addition of a suitable potential inside the box breaks the dynamical symmetry but preserves the geometrical one.The resulting degeneracy is that predicted by point-group symmetry. 1. Introduction The particle in a one-dimensional box with impenetrable walls is one of the first models discussed in most introductory books on quantum mechanics and quantum chemistry [1, 2]. It is suitable for showing how energy quantization appears as a result of certain boundary conditions. Once we have the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions for this model one can proceed to two-dimensional boxes and discuss the conditions that render the Schr¨odinger equation separable [1]. The particular case of a square box is suitable for discussing the concept of degeneracy [1]. The next step is the discussion of a particle in a three-dimensional box and in particular the cubic box as a representative of a quantum-mechanical model with high symmetry [2].