Maps Matter. the 10/40 Window and Missionary Geography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical & Contemporary Reasons for the Existence of 17,000

a HISTORICAL & CONTEMPORARY REASONS FOR THE EXISTENCE OF 17,000 UNREACHED PEOPLE GROUPS AND FACTORS BEING EMPLOYED TO LESSEN THEIR NUMBER Presented To The Department of Missions and Cross-Cultural Studies Liberty University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Cross-Cultural Studies and Church Growth by Larry W. LeGrande November 3, 1986 D - LIBERTY UNIVERSITY B.R. LAKIN SCHOOL OF RELIGION THESIS APPROVAL SHEET GRADE COMl'1ITTEE HE~i~Il)~ OR ~:~,~ READER~eJ~ z > TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .......................... 1 Chapter I. DEFINING AN UN REACHED PEOPLE GROUP 4 People Group 4 Unreached 6 Statistical Data Concerning Unreached People Groups 7 II. HISTORICAL FACTORS 10 Early Period: 30-300 A.D. 10 Medieval Period: 300-1500 10 Modern Period: 1800-1950 15 III. ATTITUDES AND PRACTICES CONTRIBUTING TO THE EXISTENCE OF UNREACHED PEOPLE GROUPS . 19 Failure to Convey a Cross-Cultural Missionary Vision to the Converts . 19 Attempting to Evangelize with Disregard for Anthropological and Sociological Principles 20 Homogeneity . 20 People Blindness 21 Ethnocentrism . 21 Superiority Complex 22 Theological Problems Present in Christianity which Affect Missionary Endeavors 23 Inerrancy . 23 Liberation Theology 24 Universalism 25 The Social Gospel . 27 Miscellaneous Problems Present in Christianity which Affect Missionary Endeavors 29 Local Evangelism is Sufficient 29 Financial . 30 Everybody is a Missionary . 31 Redefining Missiological Terms 31 Confusion over "The Call" 32 IV. CONTEMPORARY FACTORS AT WORK TO REACH THE UNREACHED 35 Identifying the Unreached 35 Tent-Making 36 People Movements . 37 Personnel Increase . 38 Application of Socio-Anthropological Principles 39 International Missionaries . 39 Media Advances . -

04-05 RDW Editorial

editorial comment In a “missiological breakthrough” breakthrough, people movement to Christ, or insider movement. If the an- patterns emerge that both conform swer is “no,” the new church movement faithfully to the Bible and swim effectively will not likely grow rapidly. within the new believers’ own culture. What About “Insider Movements”? Ralph D. Winter Gary Corwin, an outstanding mis- siologist of our time, has very helpfully (within the conversation on pages 16-23) Dear Reader, etc. However, that option may appeal raised some reasonable questions about I need to connect for you the tie that only to a few brave (or perhaps odd) this whole mysterious matter. Take a binds the two major themes of this issue souls or to individuals enamored of look at what Gary and others have to say. – the mystery of “insider movements” the Western world. Can a new believer within an “Unreached and the nitty-gritty of prioritizing some 2. Eventually, hopefully (but not al- People” follow Christ without leaving people groups above others. Let me ap- ways), a “missiological breakthrough” his culture? That is the pattern in the proach it this way: will occur. In that case both intel- New Testament with Greeks. Wow, were lectual and behavioral patterns will Greeks different from Jews! The Jews The “Reached Peoples” emerge which will both conform allowed plural marriage and abominated Suppose we track a person who comes to faithfully to the Bible and at the homosexuality, while the Greeks hated Christ within a so-called “reached group.” same time swim effectively within plural marriage but accepted homosexu- In that case several things are true: the new believers’ own culture. -

November, 2017

BELIEVERS EASTERN CHURCH Synod Secretariat, Thiruvalla, Kerala, India. SHEPHERD’S LETTER November, 2017 XGlory be to the Father the Son and the Holy Spirit. Dearly Beloved in Christ, I always thank God for each one of you! Day and night you are in my prayers as I think about your love for God and our Church, your faith in Jesus Christ and your patience and hope in following Jesus Christ. (adapted from I Thessalonians 1:2) How I wish I would be able to visit your parish and meet each one of you personally and talk to you. There are many things on my heart to tell you and I would have preferred to come to your home, sit across a table and have chai with you and tell of those things to you. However, since I cannot do that, I wish to write to you often and tell you what the Lord has put on my heart for you. In this letter I would like to introduce the topic of church calendar and its importance in our lives and how it can assist our worship. We are all familiar with seasons - like summer, winter and monsoon. In most parts of the world we have summer when it’s very hot and then winter when it becomes really cold. In some parts of our country we have monsoon, when it rains heavily. Usually we keep track of these seasons and times of the year by using a calendar. These calendars provide opportunities for us to observe important days (like Independence Day of our country) or celebrate certain events (like beginning of harvest) or even commemorate (Gandhiji’s birthday) or even our very own wedding anniversaries or birthdays. -

Horn of Africa Booklet

Challenge and Opportunity DJIBOUTI is a hot, dry desert enclave located at the Subsistence pastoral economy dominates Somalia, southeastern entrance to the Red Sea between and the people are predominantly nomadic or semi- Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia. Djibouti City, the nomadic herders. In 1969 Gen. Mohammed Siad Barre nation’s capital, is the main shipping center for the seized power and imposed a one-man rule. In 1974 he entire Horn of Africa region. About two-thirds of the evicted missionary organizations from the country. approximately 622,000 people live in the capital city. He was run out of Somalia in 1991, leaving the nation Considered to be the hottest country in the world, in desperate poverty. Subsequent clan warfare Djibouti was France’s last colony in Africa and it still caused appalling famine and destruction. The Somalis relies heavily on foreign aid from France and the believe their first ancestor was a member of the United States. At the time of its independence in Qaraysh (Koreish) tribe, to which the prophet 1977, Djibouti had very few college graduates and lit- Mohammed belonged. Today Somalia is an almost tle skilled labor. About 95 percent of the people are totally Muslim country. Its strongly oral culture loyal Muslims with strong ties to Saudi Arabia. Tension places high value on poetry, proverbs and traditional between the largest people groups — the Afar and stories. There was no written language until 1971. the Issa Somali — has caused ongoing political instabil- Somalis are remarkably homogeneous in their ity. The country has been involved in ethnic conflict laguage, culture and identity. -

Peoplegroups.Org, Joshua Project

A Model for Determining Mostthe Needy Unreached or Least-Reached Peoples Dan Scribner, Joshua Project Editor’s note: in this Mission Frontiers we return to a cover theme we last addressed almost three years ago: “Which peoples need priority attention?” To do so, we have invited Dan Scribner (director of Joshua Project) to share his perspective. For our following (January-February) issue, we have invited Todd Johnson (director of the Center for the Study of Global Christianity) to tackle the same question. Note that we have more good material than print space available, so you’ll fi nd supplemental material on both the Mission Frontiers (missionfrontiers.org) and Joshua Project (joshuaproject.net) websites. (This related material explains defi nitions, the concept of “understanding and acceptance,” and Joshua Project itself.) As always, we welcome your comments and questions in response. wo thousand years ago the Lord gave us the com- 1) Progress of, or response to the Gospel (35% mand to make followers of Christ from among all weighting, lower Christian presence = higher Tthe ethnic peoples of the world. Signifi cant seg- score). See the Joshua Project Progress Scale ments of the world are still considered (“From On/Off to a Scale” on page 9) for unreached. In the light of such great details of this measure. This scale is primarily need, how do we prioritize need in based on % Evangelical and several church- fulfi lling the unfi nished task of the planting progress indicators. This criterion is Great Commission? Our purpose given the greatest weight because it represents here is to identify criteria to determine the most important factor in measuring the the most needy unreached peoples, to progress of the Gospel in a culture. -

Table of Contents Outreach Opportunities

Outreach Opportunities Table of Contents Customized Missions Trips: We offer the following trips at any time through the year. There are specific dates on Introductory Letter -2- the website but we can also host your group any time About Global Frontier Missions -3- you want to come and serve. Why Choose GFM? -5- Missions Exposure Trips: Five Hour, One Day Trips Throughout The Year What Others Are Saying -6- Missions Explorer Trips: Weekend and Weeklong Trips What is an Unreached People Group? -8- Throughout The Year Mission Trip Program Information: 2 Types of Missions Trips -9- -9- Types of Outreach Involved -10- Registration Process -11- Policies and Procedures -13- FAQs For more information, contact us: -15- Medical and Insurance Info -15- What to Bring -16- Cultural Guidelines -18- Email: [email protected] Global Adventure Rules -20- Website: www.globalfrontiermissions.org 1 Do you want a short-term trip that makes a long-term difference? The Short Term Missions program is a strategic part of Global Frontier Missions’ full-time work, not just a way to keep your team entertained. We love hosting mission trips because of the spiritual fruit we see, both in the lives of the refugees and those who come to serve. We believe that in addition to serving the long term vision of GFM, short term missions outreaches are an integral part of every believer’s ongoing discipleship. We want to see all participants playing the role God has for each of them in fulfilling the Great Commission. GFM is known for the excellent on-field training we provide for our mission trip participants. -

Introducing East Asian Peoples

Introducing East Asian Peoples EAST ASIAN PEOPLES Contents 04 The East Asian Affinity 06 Map of East Asia 08 China 12 Japan 14 Mongolia 16 South Korea 18 Taiwan 20 Buddhism 22 Taoism or Daoism 24 Folk Religions 26 Confucianism 28 Islam 29 Atheism 30 Affinity Cities Overview 32 Unreached People Group Overview 34 Global Diaspora 36 Connect The East Asian Affinity China, Japan, Mongolia, South Korea and Taiwan, countries Issues and Challenges facing the EA Affinity In the last 10 years, Japan’s population has shifted so that 92 Aging Population on the western edge of the Pacific Ocean, are central to the percent of Japan’s people live in cities. Roughly 83 percent Japan’s population continues to decline, due to one of the work of the East Asian Peoples Affinity Group. Population of the people of South Korea live in urban areas, 20 percent world’s lowest birth rates and one-fourth of their population The population within East Asian countries is exploding. Al- in the urban area of Seoul. being 65 or older. The shrinking labor force limits tax revenue Most East Asian people live in this geographic region, but the ready, they are home to nearly 1.67 billion people, represent- and has caused Japan’s debt to grow by more than twice focus of our efforts is to communicate the gospel, helping ing a fourth of the world’s population. East Asian governments In China, there is a plan to shift 350 million rural residents into the country’s economic output. East Asian people hear and respond favorably to the Good grapple with unprecedented challenges, including how to newly constructed towns and cities by 2025. -

When-Everything-Is-Missions.Pdf

When Everything Is Missions by Denny Spitters & Matthew Ellison copyright ©2017 Pioneers-USA & Sixteen:Fifteen ISBN: 9780989954549 Scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, English Stan- dard Version® (ESV), copyright © by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. This book was published by BottomLine Media, an imprint of Pioneers, that celebrates the “bottom line” of God’s covenant with Abraham: “I will bless all nations through you.” To pur- chase other BottomLine titles, visit Pioneers.org/Store. This book is available in ebook format on Apple iBooks and Ama- zon Kindle. Printed in the USA. Reproduction in whole or in part, in any form, including storage in a memory device, is forbidden with- out express written permission, except that portions may be used in broadcast or printed commentary or review when at- tributed fully to author and publication names. PRAISE FOR WHEN EVERYTHING IS MISSIONS “Pastors, mission committees, mission agencies, and church lead- ers would do well to read the new (and short!) book, When Every- thing Is Mission. ... Spitters and Ellison remind us that if we think all of this is missions we will end up neglecting the very task laid out for us in the Great Commission. When everything is missions, missions gets left behind.” — Kevin DeYoung, Senior Pastor, Christ Covenant Church, Mathews, North Carolina “This brief, powerful and provocative book should be read by ev- ery North American pastor. Spitters and Ellison contend that when every Christian is a missionary and every ministry is missions, we gut the mandate to reach all nations. -

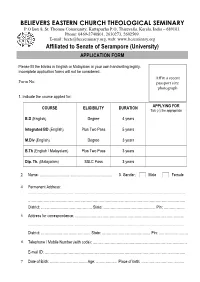

Application Form

BELIEVERS EASTERN CHURCH THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY P.O Box 8, St. Thomas Community, Kuttapuzha P.O, Thiruvalla, Kerala, India – 689103. Phone: 0469-2740801, 2630273, 2602509. E-mail: [email protected], web: www.bcseminary.org Affiliated to Senate of Serampore (University) APPLICATION FORM Please fill the blanks in English or Malayalam in your own handwriting legibly. Incomplete application forms will not be considered. Affix a recent Form No. passport size photograph 1. Indicate the course applied for: COURSE ELIGIBILITY DURATION APPLYING FOR Tick (√) the appropriate B.D (English) Degree 4 years Integrated BD (English) Plus Two Pass 5 years M.Div (English) Degree 3 years B.Th (English / Malayalam) Plus Two Pass 3 years Dip. Th. (Malayalam) SSLC Pass 3 years 2 Name: ……………………………………………………. 3. Gender: Male Female 4 Permanent Address: …………………………………………...……………………………………………………………………… …………………………………………………………….…………………………………………………….. District: …………………….……………… State: ………………..…………………… Pin: ……….…….. 5 Address for correspondence: ……………………………………………..………………………………… ……………………………………………………………….…..…………………………………………….. District: ……………………..……………. State: ………………………………….. Pin: ……..…………….. 6 Telephone / Mobile Number (with code): ………………………………….………………………………… E-mail ID: ………………………………….…………………………………………………………………… 7 Date of Birth: …………………………. Age: ……………… Place of birth: ……………………………… 8 Marital Status: Unmarried Married Other 9 Parents’ Name and Occupation: Father’s Name:…………………………………… Mother’s name: …………………………………….. Occupation:………………………………………… Occupation: ………………………………………… -

Pray 30 Days for 30 Unreached Peoples in North Carolina

30 DAYS | 30 PEOPLES PRAY 30 DAYS FOR 30 UNREACHED PEOPLES IN NORTH CAROLINA Prayer Profiles Intro Welcome to the prayer guide for some of the unreached people groups (UPG) who have made their homes in North Carolina. It is our hope that as you read the profiles of each of these people groups, you will be moved to pray fervently that believers will take the gospel to them. An unreached people group is defined as a grouping of people who share the same ethnicity and language and whose home country is less than 2 percent evangelical Christian. Currently, at least 154 unreached people groups have been identified with sizeable populations here in North Carolina. Today, upwards of 15 percent of North Carolina’s population — that is 1.5 million people — are foreign-born or are the children of foreign-born immigrants. Almost all of these people have never heard the gospel clearly presented either in their home countries or since they planted their lives in North Carolina. While in Athens, the Apostle Paul declared, “And [God] made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place, that they should seek God, and perhaps feel their way toward Him and find Him” (Acts 17:26-27). It is our conviction that God has brought these peoples here in order that they might hear the gospel. Thank you for taking the time to pray that the gospel will come to these unreached people groups. -

Finishing the Task: the Unreached Peoples Challenge

Finishing the Task The Unreached Peoples Challenge Ralph D. Winter and Bruce A. Koch Look at the nations and watch—and be utterly amazed. For I am going to do something in your days that you would not believe, even if you were told. — Habakkuk 1:5 od’s promise to bless all the “families of the earth,” first given to Abraham 4,000 years ago, is becom- Ralph D. Winter ing a reality at a pace “you would not believe.” is the General Although some may dispute some of the details, the overall Director of the G trend is indisputable. Biblical faith is growing and spreading Frontier Mission to the ends of the earth as never before in history. Fellowship (FMF) in The Amazing Progress of the Gospel Pasadena, CA. After serving ten One of every eight people on the planet is a practicing Chris- years as a missionary among tian who is active in his/her faith. The number of believers in Mayan Indians in the highlands what used to be “mission fields” now surpasses the number of of Guatemala, he was called believers in the countries from which missionaries were origi- to be a Professor of Missions at nally sent. In fact, more missionaries are now sent from non- the School of World Mission at Western churches than from the traditional mission-sending Fuller Theological Seminary. Ten bases in the West. The Protestant growth rate in Latin America years later, he and his late wife, is well over three times the biological growth rate. Protestants Roberta, founded the mission society called the Frontier Mission Fellowship. -

Choose Life Vol

May/June 2019 Faith Fellowship Choose Life Vol. 86, No. 3 THEOLOGY DISCIPLE-MAKING INTERNATIONAL MISSION His Mercy is p. 3 North American p. 12 p. 16 Great Mission: Restructure Reaching the Unreached CLB www.CLBA.org CLB Living with Abortion 4 Anonymous FF Help and Healing Melinda Gardner FAITH & FELLOWSHIP 5 Volume 86 - Number 3 Walking Home fizkes/iStock Adrienne Droogsma Editor In Chief/ 6 Troy Tysdal Graphic Designer: Resurrection [email protected] Daniel Berge 8 Contributing Editor: Brent Juliot [email protected] CLB Copy Editor: Aaron Juliot [email protected] Cover Photo: F cusROY HEGGLAND Resurrection/azur13/iStock olesiabilkei/iStock All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise Changes Proposed Missionary Update indicated, are taken from the HOLY for WMCLB Danny B. 11 Cheryl Olsen 18 BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV®. Copyright ©1973, NAM Restructure CLB News 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used 12 Paul Larson 19 by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com Cultivate re:Think The “NIV” and “New International New England Brent Juliot 14 Michael Natale 20 Version” are trademarks registered in The Bronson Family/2018 the United States Patent and Trademark Reaching the Unreached Office by Biblica, Inc.™ 16 Ethan Christofferson Quiet Moments Email prayer requests to: [email protected] tell us that it is God who knits a child together (Psalm 139:13), and even that the Leap for Joy infant John the Baptist leapt for joy in his TROY TYSDAL mother’s womb when he first heard the voice of Mary—the mother of his Lord KristiLinton/iStock (Luke 1:44).