Integration and Black Protest in Michigan State University Football, 1947-1972

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of an Offensive Signal System Using Words Rather Than Numbers and Including Automatics

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1958 A study of an offensive signal system using words rather than numbers and including automatics Don Carlo Campora University of the Pacific Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Health and Physical Education Commons Recommended Citation Campora, Don Carlo. (1958). A study of an offensive signal system using words rather than numbers and including automatics. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/ 1369 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r, i I l I I\ IIi A ..STUDY OF AN OFFENSIVE SIGNAL SYSTEM USING WORDS RATHER THAN NUMBERS AND INCLUDING AUTOMATICS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Physical Education College of the Pacific In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree .Master of Arts by Don Carlo Campora .. ,.. ' TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION • . .. • . .. • • 1 Introductory statement • • 0 • • • • • • • 1 The Problem • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. 4 Statement of the problem • • • • • • 4 Importance of the topic • • • 4 Related Studies • • • • • • • • • • • 9 • • 6 Definitions of Terms Used • • • • • • • • 6 Automatics • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Numbering systems • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Defense • • • • • • • • • • o- • • • 6 Offense • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Starting count • • • • • • • • 0 6 "On" side • • • • • • • • 0 • 6 "Off" side • " . • • • • • • • • 7 Scouting report • • • • • • • • 7 Variations • • .. • 0 • • • • • • • • • 7 Organization of the Study • • • • • • • • • • • 7 Review of the literature • • • • . -

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of NYC”: The

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa B.A. in Italian and French Studies, May 2003, University of Delaware M.A. in Geography, May 2006, Louisiana State University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by Suleiman Osman Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University certifies that Elizabeth Healy Matassa has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 21, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 Elizabeth Healy Matassa Dissertation Research Committee: Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Elaine Peña, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member Elizabeth Chacko, Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this dissertation to the five boroughs. From Woodlawn to the Rockaways: this one’s for you. iv Abstract of Dissertation “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 This dissertation argues that New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis was not only an economic crisis, but was also a spatial and embodied one. -

Football Coaching Records

FOOTBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Coaching Records 5 Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) Coaching Records 15 Division II Coaching Records 26 Division III Coaching Records 37 Coaching Honors 50 OVERALL COACHING RECORDS *Active coach. ^Records adjusted by NCAA Committee on Coach (Alma Mater) Infractions. (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. Note: Ties computed as half won and half lost. Includes bowl 25. Henry A. Kean (Fisk 1920) 23 165 33 9 .819 (Kentucky St. 1931-42, Tennessee St. and playoff games. 44-54) 26. *Joe Fincham (Ohio 1988) 21 191 43 0 .816 - (Wittenberg 1996-2016) WINNINGEST COACHES ALL TIME 27. Jock Sutherland (Pittsburgh 1918) 20 144 28 14 .812 (Lafayette 1919-23, Pittsburgh 24-38) By Percentage 28. *Mike Sirianni (Mount Union 1994) 14 128 30 0 .810 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four- (Wash. & Jeff. 2003-16) year NCAA colleges regardless of division. 29. Ron Schipper (Hope 1952) 36 287 67 3 .808 (Central [IA] 1961-96) Coach (Alma Mater) 30. Bob Devaney (Alma 1939) 16 136 30 7 .806 (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. (Wyoming 1957-61, Nebraska 62-72) 1. Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) 27 332 24 3 .929 31. Chuck Broyles (Pittsburg St. 1970) 20 198 47 2 .806 (Mount Union 1986-2012) (Pittsburg St. 1990-2009) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) 13 105 12 5 .881 32. Biggie Munn (Minnesota 1932) 10 71 16 3 .806 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Albright 1935-36, Syracuse 46, Michigan 3. -

Event Winners

Meet History -- NCAA Division I Outdoor Championships Event Winners as of 6/17/2017 4:40:39 PM Men's 100m/100yd Dash 100 Meters 100 Meters 1992 Olapade ADENIKEN SR 22y 292d 10.09 (2.0) +0.09 2017 Christian COLEMAN JR 21y 95.7653 10.04 (-2.1) +0.08 UTEP {3} Austin, Texas Tennessee {6} Eugene, Ore. 1991 Frank FREDERICKS SR 23y 243d 10.03w (5.3) +0.00 2016 Jarrion LAWSON SR 22y 36.7652 10.22 (-2.3) +0.01 BYU Eugene, Ore. Arkansas Eugene, Ore. 1990 Leroy BURRELL SR 23y 102d 9.94w (2.2) +0.25 2015 Andre DE GRASSE JR 20y 215d 9.75w (2.7) +0.13 Houston {4} Durham, N.C. Southern California {8} Eugene, Ore. 1989 Raymond STEWART** SR 24y 78d 9.97w (2.4) +0.12 2014 Trayvon BROMELL FR 18y 339d 9.97 (1.8) +0.05 TCU {2} Provo, Utah Baylor WJR, AJR Eugene, Ore. 1988 Joe DELOACH JR 20y 366d 10.03 (0.4) +0.07 2013 Charles SILMON SR 21y 339d 9.89w (3.2) +0.02 Houston {3} Eugene, Ore. TCU {3} Eugene, Ore. 1987 Raymond STEWART SO 22y 80d 10.14 (0.8) +0.07 2012 Andrew RILEY SR 23y 276d 10.28 (-2.3) +0.00 TCU Baton Rouge, La. Illinois {5} Des Moines, Iowa 1986 Lee MCRAE SO 20y 136d 10.11 (1.4) +0.03 2011 Ngoni MAKUSHA SR 24y 92d 9.89 (1.3) +0.08 Pittsburgh Indianapolis, Ind. Florida State {3} Des Moines, Iowa 1985 Terry SCOTT JR 20y 344d 10.02w (2.9) +0.02 2010 Jeff DEMPS SO 20y 155d 9.96w (2.5) +0.13 Tennessee {3} Austin, Texas Florida {2} Eugene, Ore. -

Division I Men's Outdoor Track Championships Records Book

DIVISION I MEN’S OUTDOOR TRACK CHAMPIONSHIPS RECORDS BOOK 2020 Championship 2 History 2 All-Time Team Results 30 2020 CHAMPIONSHIP The 2020 championship was not contested due to the COVID-19 pandemic. HISTORY TEAM RESULTS (Note: No meet held in 1924.) †Indicates fraction of a point. *Unofficial champion. Year Champion Coach Points Runner-Up Points Host or Site 1921 Illinois Harry Gill 20¼ Notre Dame 16¾ Chicago 1922 California Walter Christie 28½ Penn St. 19½ Chicago 1923 Michigan Stephen Farrell 29½ Mississippi St. 16 Chicago 1925 *Stanford R.L. Templeton 31† Chicago 1926 *Southern California Dean Cromwell 27† Chicago 1927 *Illinois Harry Gill 35† Chicago 1928 Stanford R.L. Templeton 72 Ohio St. 31 Chicago 1929 Ohio St. Frank Castleman 50 Washington 42 Chicago 22 1930 Southern California Dean Cromwell 55 ⁄70 Washington 40 Chicago 1 1 1931 Southern California Dean Cromwell 77 ⁄7 Ohio St. 31 ⁄7 Chicago 1932 Indiana Billy Hayes 56 Ohio St. 49¾ Chicago 1933 LSU Bernie Moore 58 Southern California 54 Chicago 7 1934 Stanford R.L. Templeton 63 Southern California 54 ⁄20 Southern California 1935 Southern California Dean Cromwell 741/5 Ohio St. 401/5 California 1936 Southern California Dean Cromwell 103⅓ Ohio St. 73 Chicago 1937 Southern California Dean Cromwell 62 Stanford 50 California 1938 Southern California Dean Cromwell 67¾ Stanford 38 Minnesota 1939 Southern California Dean Cromwell 86 Stanford 44¾ Southern California 1940 Southern California Dean Cromwell 47 Stanford 28⅔ Minnesota 1941 Southern California Dean Cromwell 81½ Indiana 50 Stanford 1 1942 Southern California Dean Cromwell 85½ Ohio St. 44 ⁄5 Nebraska 1943 Southern California Dean Cromwell 46 California 39 Northwestern 1944 Illinois Leo Johnson 79 Notre Dame 43 Marquette 3 1945 Navy E.J. -

42Nd Sports Winners Press Release

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES THE WINNERS OF THE 42nd ANNUAL SPORTS EMMY® AWARDS Ceremony Highlights Women in Sports Television and HBCUs New York, NY - June 8, 2021 - The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) announced tonight the winners of the 42nd Annual Sports Emmy® Awards. which were live-streamed at Watch.TheEmmys.TV and available on the various Emmy® apps for iOS, tvOS, Android, FireTV, and Roku (full list at apps.theemmys.tv/). The live-virtual presentation was filled with a star-studded group of sports television personalities as presenters such as Emmanuel Acho, Studio Host (FOX), Nate Burleson, Studio Analyst (CBS Sports), Fran Charles, Studio Host (MLB Network), Jim Gray, Sportscaster (Showtime), Andrew Hawkins Studio Analyst (NFL Network), Andrea Kremer, Correspondent (HBO), Laura Rutledge, Studio Host (ESPN), Mike Tirico, Studio Host (NBC Sports) and Matt Winer, Studio Host (Turner). With more women nominated in sports personality categories than ever before, there was a special roundtable celebrating this accomplishment introduced by WNBA player Asia Durr that included most of the nominated female sportscasters such as Erin Andrews (FOX), Ana Jurka (Telemundo), Adriana Monsalve (Univision/TUDN), Rachel Nichols (ESPN), Pilar Pérez (ESPN Deportes), Lisa Salters (ESPN) and Tracy Wolfson (CBS). In addition to this evening’s distinguished nominees and winners, Elle Duncan, anchor (ESPN) announced a grant to historically black colleges/universities (HBCUs) sponsored by Coca-Cola honoring a HBCU student studying for a career in sports journalism administered by the National Academy’s Foundation. Winners were announced in 46 categories including Outstanding Live Sports Special, Live Sports Series and Playoff Coverage, three Documentary categories, Outstanding Play-by-Play Announcer, Studio Host, and Emerging On-Air Talent, among others. -

The Montana Kaimin, October 11, 1932

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 10-11-1932 The onM tana Kaimin, October 11, 1932 Associated Students of the State University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the State University of Montana, "The onM tana Kaimin, October 11, 1932" (1932). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 1375. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/1375 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA. MISSOULA, MONTANA TUESDAY. OCTOBER II, 1932 VOLUME XXXII. No. 5 Mortar Board National Convention Coleman and Little Three Plays Grizzlies Overcome First-Quarter Recommends Constitution Changes Manage Broadcasts A re Selected Lead to Defeat Hilltoppers, 14-6 Doris Kindschy Is Elected President of Honorary Organization to Take State University Will Sponsor New Fumble on First Kick-off Paves Way for Carroll’s Only Touchdown; Feature In Radio Programs Place Left By Frances UDman By Masquers Stansberry Twice Carries BaD Over Line A series of weekly radio programs Mortar Board, senior women's national honorary, Friday afternoon entitled “College Knowledge,” is now Nineteen Students Cast for Roles Montana’s Grizzlies launched an irresistible attack in the third elected as its president, Doris Kindschy of Lewistown, to take the being sponsored by the State Univer By Hewitt; One-acts Will quarter to win over Carroll college Saturday, 14 to 6. -

BOWL HISTORY S E a BOWL HISTORY 1938 ORANGE BOWL I C I D Michigan State Football Teams Have Appeared in 17 Postseason Bowl Games, Including Seven New V JAN

BOWL HISTORY S E A BOWL HISTORY 1938 ORANGE BOWL I C I D Michigan State football teams have appeared in 17 postseason bowl games, including seven New V JAN. 1, 1938 | MIAMI, FLA. | ATT: 18,970 E R M Year’s Day games. The Spartans are 7-10 (.412) in bowl games. E 1 234 F S • Michigan State’s 37-34 win over No. 10 Florida in the 2000 Florida Citrus Bowl marked its MSU 0 000 0 first New Year’s Day bowl victory since the 1988 Rose Bowl and ended a four-game losing AUBURN 0600 6 streak in postseason play. The fourth annual Orange Bowl game wasn’t nearly as close as the final score might indicate K • Each of Michigan State’s last four bowl opponents have been ranked in The Associated Press O 6 as Auburn dominated play on both sides of the football in recording a shutout victory, 6-0, over O 0 Top 25, including No. 22 Nebraska in the 2003 Alamo Bowl, No. 20 Fresno State in the 2001 L Michigan State. It still ranks as the lowest-scoring game in Orange Bowl history. Auburn wasted 0 T Silicon Valley Football Classic, No. 10 Florida in the 2000 Florida Citrus Bowl and No. 21 U 2 two scoring opportunities in the first quarter. Jimmy Fenton’s 25-yard run gave the Tigers a first- O Washington in the 1997 Aloha Bowl. and-10 at the MSU 12 but the Spartan defense responded by stuffing three-straight running • During his 12-year tenure (1983-94), George Perles took Michigan State to seven bowl plays and Lyle Rockenbach broke up Fenton’s fourth-down pass. -

The BG News December 5, 2000

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 12-5-2000 The BG News December 5, 2000 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News December 5, 2000" (2000). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6731. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6731 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Green State University TUESDAY December 5, 2000 MOSTLY CLOUDY HIGH: 261 LOW 6 www.bgnews.com independent student press VOLUME 90 ISSUE 66 FOOTBALL GOES URBAN 'URBAN' LEGEND: The new Bowling Green State University Head Football Coach. Urban Meyer, addresses the media during a press conterence yesterday, where Athletics Director. Paul Krebs, named Meyer as the new coach. MEYER'S CAREER Alone It"! way lie's stopped at live schools. Hoes a time lite 1985 Cincinnati. Student Mey<er takes over as head coach Assistant Coach 198f> Ohio Slate. Graduate and the distant future tor our Assistant, Tight Ends football program." 1987 Ohio Mate. Graduate Football program looks to Fall for new start With the possibility of 1(X) per- Assistant. Receivers cent of the Falcons rushing, pass 1988 Illinois State, Outside linebackers By Pete Stella Green Mate University and the coaches such as Earl Bruce, Lou es, someone who is familiar with ing, receiving, scoring and all 1989 Intro •on man to lead our football pro- 1 lolt/and Sonny l.ubick will help the Midwest and a person who purpose attack (liming bark. -

Race and College Football in the Southwest, 1947-1976

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE DESEGREGATING THE LINE OF SCRIMMAGE: RACE AND COLLEGE FOOTBALL IN THE SOUTHWEST, 1947-1976 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By CHRISTOPHER R. DAVIS Norman, Oklahoma 2014 DESEGREGATING THE LINE OF SCRIMMAGE: RACE AND COLLEGE FOOTBALL IN THE SOUTHWEST, 1947-1976 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ____________________________ Dr. Stephen H. Norwood, Chair ____________________________ Dr. Robert L. Griswold ____________________________ Dr. Ben Keppel ____________________________ Dr. Paul A. Gilje ____________________________ Dr. Ralph R. Hamerla © Copyright by CHRISTOPHER R. DAVIS 2014 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements In many ways, this dissertation represents the culmination of a lifelong passion for both sports and history. One of my most vivid early childhood memories comes from the fall of 1972 when, as a five year-old, I was reading the sports section of one of the Dallas newspapers at my grandparents’ breakfast table. I am not sure how much I comprehended, but one fact leaped clearly from the page—Nebraska had defeated Army by the seemingly incredible score of 77-7. Wild thoughts raced through my young mind. How could one team score so many points? How could they so thoroughly dominate an opponent? Just how bad was this Army outfit? How many touchdowns did it take to score seventy-seven points? I did not realize it at the time, but that was the day when I first understood concretely the concepts of multiplication and division. Nebraska scored eleven touchdowns I calculated (probably with some help from my grandfather) and my love of football and the sports page only grew from there. -

Illinois ... Football Guide

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign !~he Quad s the :enter of :ampus ife 3 . H«H» H 1 i % UI 6 U= tiii L L,._ L-'IA-OHAMPAIGK The 1990 Illinois Football Media Guide • The University of Illinois . • A 100-year Tradition, continued ~> The University at a Glance 118 Chronology 4 President Stanley Ikenberrv • The Athletes . 4 Chancellor Morton Weir 122 Consensus All-American/ 5 UI Board of Trustees All-Big Ten 6 Academics 124 Football Captains/ " Life on Campus Most Valuable Players • The Division of 125 All-Stars Intercollegiate Athletics 127 Academic All-Americans/ 10 A Brief History Academic All-Big Ten 11 Football Facilities 128 Hall of Fame Winners 12 John Mackovic 129 Silver Football Award 10 Assistant Coaches 130 Fighting Illini in the 20 D.I.A. Staff Heisman Voting • 1990 Outlook... 131 Bruce Capel Award 28 Alpha/Numerical Outlook 132 Illini in the NFL 30 1990 Outlook • Statistical Highlights 34 1990 Fighting Illini 134 V early Statistical Leaders • 1990 Opponents at a Glance 136 Individual Records-Offense 64 Opponent Previews 143 Individual Records-Defense All-Time Record vs. Opponents 41 NCAA Records 75 UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 78 UI Travel Plans/ 145 Freshman /Single-Play/ ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN Opponent Directory Regular Season UNIVERSITY OF responsible for its charging this material is • A Look back at the 1989 Season Team Records The person on or before theidue date. 146 Ail-Time Marks renewal or return to the library Sll 1989 Illinois Stats for is $125.00, $300.00 14, Top Performances minimum fee for a lost item 82 1989 Big Ten Stats The 149 Television Appearances journals. -

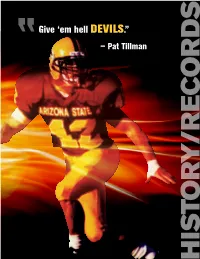

Give 'Em Hell Devils.”

Give ‘em hell DEVILS.” ” — Pat Tillman HISTORY/RECORDS Year-BY-Year StatiSticS RUSHING PASSING TOTAL OFFENSE PUNTS SCORING FIRST DOWNS Year Att.-Yds.-TD Avg./G A-C-I-TD Yds. Avg./G Pl.-Yds. Avg./G No. Avg. TD C-1 C-2 FG Pts. Avg./G R P Pn Tot. 1946 ASU (11) 451-870-NA 79.1 241-81-30-NA 1,073 97.6 692-1,943 176.6 81 34.6 14 7-14 0-0 0 93 8.5 49 41 11 101 Opponents 507-2,244-NA 204.0 142-61-9-NA 1,101 100.1 649-3,345 304.1 60 28.0 47 31-47 0-0 0 313 28.5 87 36 5 128 1947 ASU (11) 478-2,343-NA 213.0 196-77-15-NA 913 83.0 674-3,256 296.0 62 34.8 26 11-26 0-0 0 168 15.3 101 36 8 145 Opponents 476-2,251-NA 204.6 163-51-19-NA 751 68.3 639-3,002 272.9 69 34.2 35 24-35 0-0 0 234 21.3 96 20 5 121 1948 ASU (10) 499-2,188-NA 218.8 183-85-9-NA 1,104 110.4 682-3,292 329.2 40 32.5 41 20-41 0-0 3 276 27.6 109 46 8 163 Opponents 456-2,109-NA 210.9 171-68-19-NA 986 98.6 627-3,095 309.5 53 33.6 27 22-27 0-0 2 192 19.2 81 38 6 125 1949 ASU (9) 522-2,968-NA 329.8 144-56-17-NA 1,111 123.4 666-4,079 453.2 33 37.1 47 39-47 0-0 0 321 35.7 – – – 173 Opponents 440-1,725-NA 191.7 140-50-20-NA 706 78.4 580-2,431 270.1 61 34.7 26 15-26 0-0 0 171 19.0 – – – 111 1950 ASU (11) 669-3,710-NA 337.3 194-86-21-NA 1,405 127.7 863-5,115 465.0 51 36.1 58 53-58 0-0 1 404 36.7 178 53 11 242 Opponents 455-2,253-NA 304.5 225-91-27-NA 1,353 123.0 680-3,606 327.8 74 34.6 23 16-23 0-0 0 154 14.0 78 51 8 137 1951 ASU (11) 559-3,350-NA 145.8 130-51-11-NA 814 74.0 689-4,164 378.5 48 34.3 45 32-45 0-0 2 308 28.0 164 27 8 199 Opponents 494-1,604-NA 160.4 206-92-10-NA 1,426 129.6 700-3,030