Mapping African American Women's Public Memorialization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“A Greater Compass of Voice”: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Ann Shadd Cary Navigate Black Performance Kristin Moriah

Document generated on 10/01/2021 9:01 a.m. Theatre Research in Canada Recherches théâtrales au Canada “A Greater Compass of Voice”: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Ann Shadd Cary Navigate Black Performance Kristin Moriah Volume 41, Number 1, 2020 Article abstract The work of Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Ann Shadd Cary URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1071754ar demonstrate how racial solidarity between Black Canadians and African DOI: https://doi.org/10.3138/tric.41.1.20 Americans was created through performance and surpassed national boundaries during the nineteenth century. Taylor Greenfield’s connection to See table of contents Mary Ann Shadd Cary, the prominent feminist abolitionist, and the first Black woman to publish a newspaper in North America, reveals the centrality of peripatetic Black performance, and Black feminism, to the formation of Black Publisher(s) Canada’s burgeoning community. Her reception in the Black press and her performance work shows how Taylor Greenfield’s performances knit together Graduate Centre for the Study of Drama, University of Toronto various ideas about race, gender, and nationhood of mid-nineteenth century Black North Americans. Although Taylor Greenfield has rarely been recognized ISSN for her role in discourses around race and citizenship in Canada during the mid-nineteenth century, she was an immensely influential figure for both 1196-1198 (print) abolitionists in the United States and Blacks in Canada. Taylor Greenfield’s 1913-9101 (digital) performance at an event for Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s benefit testifies to the longstanding porosity of the Canadian/ US border for nineteenth century Black Explore this journal North Americans and their politicized use of Black women’s voices. -

Negroes Are Different in Dixie: the Press, Perception, and Negro League Baseball in the Jim Crow South, 1932 by Thomas Aiello Research Essay ______

NEGROES ARE DIFFERENT IN DIXIE: THE PRESS, PERCEPTION, AND NEGRO LEAGUE BASEBALL IN THE JIM CROW SOUTH, 1932 BY THOMAS AIELLO RESEARCH ESSAY ______________________________________________ “Only in a Negro newspaper can a complete coverage of ALL news effecting or involving Negroes be found,” argued a Southern Newspaper Syndicate advertisement. “The good that Negroes do is published in addition to the bad, for only by printing everything fit to read can a correct impression of the Negroes in any community be found.”1 Another argued that, “When it comes to Negro newspapers you can’t measure Birmingham or Atlanta or Memphis Negroes by a New York or Chicago Negro yardstick.” In a brief section titled “Negroes Are Different in Dixie,” the Syndicate’s evaluation of the Southern and Northern black newspaper readers was telling: Northern Negroes may ordain it indecent to read a Negro newspaper more than once a week—but the Southern Negro is more consolidated. Necessity has occasioned this condition. Most Southern white newspapers exclude Negro items except where they are infamous or of a marked ridiculous trend… While his northern brother is busily engaged in ‘getting white’ and ruining racial consciousness, the Southerner has become more closely knit.2 The advertisement was designed to announce and justify the Atlanta World’s reformulation as the Atlanta Daily World, making it the first African-American daily. This fact alone probably explains the advertisement’s “indecent” comment, but its “necessity” argument seems far more legitimate.3 For example, the 1932 Monroe Morning World, a white daily from Monroe, Louisiana, provided coverage of the black community related almost entirely to crime and church meetings. -

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will Local News Survive?

NEWS DESERTS AND GHOST NEWSPAPERS: WILL LOCAL NEWS SURVIVE? PENELOPE MUSE ABERNATHY Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics Will Local News Survive? | 1 NEWS DESERTS AND GHOST NEWSPAPERS: WILL LOCAL NEWS SURVIVE? By Penelope Muse Abernathy Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics The Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media School of Media and Journalism University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2 | Will Local News Survive? Published by the Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media with funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Office of the Provost. Distributed by the University of North Carolina Press 11 South Boundary Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514-3808 uncpress.org Will Local News Survive? | 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 5 The News Landscape in 2020: Transformed and Diminished 7 Vanishing Newspapers 11 Vanishing Readers and Journalists 21 The New Media Giants 31 Entrepreneurial Stalwarts and Start-Ups 40 The News Landscape of the Future: Transformed...and Renewed? 55 Journalistic Mission: The Challenges and Opportunities for Ethnic Media 58 Emblems of Change in a Southern City 63 Business Model: A Bigger Role for Public Broadcasting 67 Technological Capabilities: The Algorithm as Editor 72 Policies and Regulations: The State of Play 77 The Path Forward: Reinventing Local News 90 Rate Your Local News 93 Citations 95 Methodology 114 Additional Resources 120 Contributors 121 4 | Will Local News Survive? PREFACE he paradox of the coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing economic shutdown is that it has exposed the deep Tfissures that have stealthily undermined the health of local journalism in recent years, while also reminding us of how important timely and credible local news and information are to our health and that of our community. -

90 Day Report, a Review of the 2000 Legislative Session

The 90 Day Report A Review of the 2000 Legislative Session Department of Legislative Services Office of the Executive Director Maryland General Assembly April 14, 2000 Honorable Thomas V. Mike Miller, Jr., President of the Senate Honorable Casper R. Taylor, Jr., Speaker of the House of Delegates Honorable Members of the General Assembly Ladies and Gentlemen: I am pleased to present you with The 90 Day Report - A Review of Legislation in the 2000 Session. The 90 Day Report consists of two volumes. Volume I is divided into 13 parts, each dealing with a major policy area. Each part contains a discussion of the majority of bills passed in that policy area, including comparisons with previous sessions and current law, background information, and a discussion of significant bills that did not pass. Information relating to the Operating Budget, Capital Budget, and aid to local governments is found in Part A of this volume. Volume II, organized in the same manner as Volume I, consists of a list of all bills passed and a short synopsis stating the purpose of each bill. As was the case last year, The 90 Day Report is being provided to you in loose-leaf format to make it easier to copy and use parts of the report. The binders provided last year were designed to hold the most recent edition of The 90 Day Report; please use the binder provided last year for this year's report. Should you also wish to have a bound version of the Report, please contact my office. I hope that you will find The 90 Day Report as helpful this year as you have in the past. -

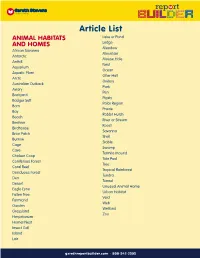

Article List

Article List ANIMAL HABITATS Lake or Pond AND HOMES Lodge Meadow African Savanna Mountain Antarctic Mouse Hole Anthill Nest Aquarium Ocean Aquatic Plant Otter Holt Arctic Owlery Australian Outback Park Aviary Pen Backyard Pigsty Badger Sett Polar Region Barn Prairie Bay Rabbit Hutch Beach River or Stream Beehive Roost Birdhouse Savanna Briar Patch Shell Burrow Stable Cage Swamp Cave Termite Mound Chicken Coop Tide Pool Coniferous Forest Tree Coral Reef Tropical Rainforest Deciduous Forest Tundra Den Tunnel Desert Unusual Animal Home Eagle Eyrie Urban Habitat Fallen Tree Veld Farmland Web Garden Wetland Grassland Zoo Herpetarium Hornet Nest Insect Gall Island Lair Article List BIRDS Flamingos Geese African Crowned Cranes Golden Pheasants African Gray Parrots Greater Roadrunners Albatrosses Guam Rails Amazon Parrots Hawks American Robins Hermit Thrushes Arctic Terns Hummingbirds Bald Eagles Ibises Baltimore Orioles Kakapos Bananaquits Kingfishers Birds-of-Paradise Kiwis Black Phoebes Lark Buntings Black-Capped Chickadees Macaws Blue Hen Chickens Mariana Fruit-Doves Blue Jays Mockingbirds Blue-Footed Boobies Mountain Bluebirds Bobwhite Quails Mourning Doves Brown Pelicans Nenes Brown Thrashers Northern Flickers Budgerigars Orioles Cactus Wrens Ospreys California Condors Ostriches California Gulls Owls California Valley Quails Peacocks Cardinals Pelicans Carolina Wrens Penguins Cedar Waxwings Peregrine Falcons Chickens Puerto Rican Spindalises Cockatiels Puffins Cockatoos Purple Finches Common Loons Quetzals Crows Red-Tailed Hawks Dodos Rhode -

The Iowa Bystander

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1983 The oI wa Bystander: a history of the first 25 years Sally Steves Cotten Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Cotten, Sally Steves, "The oI wa Bystander: a history of the first 25 years" (1983). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16720. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16720 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Iowa Bystander: A history of the first 25 years by Sally Steves Cotten A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1983 Copyright © Sally Steves Cotten, 1983 All rights reserved 144841,6 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENT iii I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE EARLY YEARS 13 III. PULLING OURSELVES UP 49 IV. PREJUDICE IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA 93 V. FIGHTING FOR DEMOCRACY 123 VI. CONCLUSION 164 VII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 175 VIII. APPENDIX A STORY AND FEATURE ILLUSTRATIONS 180 1894-1899 IX. APPENDIX B ADVERTISING 1894-1899 182 X. APPENDIX C POLITICAL CARTOONS AND LOGOS 1894-1899 184 XI. -

New LAPD Chief Shares His Policing Vision with South L.A. Black Leaders

Abess Makki Aims to Mitigate The Overcomer – Dr. Bill Water Crises First in Detroit, Then Releford Conquers Major Setback Around the World to Achieve Professional Success (See page A-3) (See page C-1) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBERSEPTEMBER 12 17,- 18, 2015 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO 25 $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over EightyYears TheYears Voice The ofVoice Our of Community Our Community Speaking Speaking for Itselffor Itself” THURSDAY, JUNE 21, 2018 The event was a 'thank you card' to the Los Angeles community for a rich history of support and growth together. The organization will continue to celebrate its 50th milestone throughout the year. SPECIAL TO THE SENTINEL Proclamations and reso- lutions were awarded to the The Brotherhood Cru- organization, including a sade, is a community orga- U.S. Congressional Records nization founded in 1968 Resolution from the 115th by civil rights activist Wal- Congress (House of Repre- ter Bremond. For 35 years, sentatives) Second Session businessman, publisher and by Congresswoman Karen civil rights activist Danny J. Bass, 37th Congressional Bakewell, Sr. led the Institu- District of California. tion and last week, Brother- Distinguished guests hood Crusade president and who attended the event in- CEO Charisse Bremond cluded: Weaver hosted a 50th Anni- CA State Senator Holly versary Community Thank Mitchell; You Event on Friday, June CA State Senator Steve 15, 2018 at the California CA State Assemblymember Science Center in Exposi- Reggie Jones-Sawyer; tion Park. civil rights advocate and The event was designed activist Danny J. -

Challenges and Solutions for National Park Service Civil War Sites Working with African American Communities

Stephen F. Austin State University SFA ScholarWorks Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-12-2018 CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS FOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CIVIL WAR SITES WORKING WITH AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITIES Rolonda Teal Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/etds Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Repository Citation Teal, Rolonda, "CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS FOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CIVIL WAR SITES WORKING WITH AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITIES" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 165. https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/etds/165 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS FOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CIVIL WAR SITES WORKING WITH AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITIES Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This dissertation is available at SFA ScholarWorks: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/etds/165 CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS FOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CIVIL WAR SITES WORKING WITH AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITIES By ROLONDA DENISE TEAL, Master of Science in Anthropology Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Stephen F. Austin State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy STEPHEN F. AUSTIN STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2018 CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS FOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CIVIL WAR SITES WORKING WITH AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITIES By ROLONDA DENISE TEAL, Master of Science in Anthropology APPROVED: _______________________________________ Dr. -

Columbia, South Carolina A

THE SEPTEMBER 2015 LEGIONARY A Publication of the Sons of Confederate Veterans Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton Camp No. 273 Columbia, South Carolina www.wadehamptoncamp.org Charles Bray, Acting Editor A FRATERNAL ORGANIZATION OF SOUTHERN MEN SPEAKER’S BIO AND TOPIC WADE HAMPTON CAMP MONTHLY MEETING SEPTEMBER 17, 2015 Our next Camp meeting on the 17th will be presented by Jim Ridge. Jim will reinvigorate each of us in a program titled, Southern Heritage Explained. Jim will remind us of our rich Southern heritage and culture. You will be enlightened, enriched and entertained. COMMANDERS CORNER TERRY HUGHEY What next? What do we do now? Will it ever stop? I want each of us to think of our current struggle to preserve our Confederate soldier’s good name, as well as our southern virtues and culture, along with our Christian faith as a 15 round world championship title bout. The first round, summer of 2015, we were knocked down hard. Yes, we were staggered as the blow was an unexpected mass murder perpetrated by a mad man which resulted in what has to be as the most perfect media storm ever seen. As we strive to fight back into round 2, and tried to regain our composure we were struck several more times to our chin, our stomach and several illegal blows to our groin. Our own corner tried to throw in the towel, as they abandoned us in the fight of the Century. Yes, we have made it to round 2 and have thrown some punches of our own. Our first punch landed on Saturday, August 29 with a 80 vehicle flag caravan around Columbia two times. -

Vanderbilt University, Department of Physics & Astronomy VU Station B

CURRICULUM VITAE: KEIVAN GUADALUPE STASSUN SENIOR ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR GRADUATE EDUCATION & RESEARCH, COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCE Vanderbilt University, Department of Physics & Astronomy VU Station B 1807, Nashville, TN 37235 Phone: 615-322-2828, FAX: 615-343-7263 [email protected] DEGREES EARNED University of Wisconsin—Madison Degree: Ph.D. in Astronomy, 2000 Thesis: Rotation, Accretion, and Circumstellar Disks among Low-Mass Pre-Main-Sequence Stars Advisor: Robert D. Mathieu University of California at Berkeley Degree: A.B. in Physics/Astronomy (double major) with Honors, 1994 Thesis: A Simultaneous Photometric and Spectroscopic Variability Study of Classical T Tauri Stars Advisor: Gibor Basri EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Vanderbilt University Director, Vanderbilt Center for Autism & Innovation, 2017-present Stevenson Endowed Professor of Physics & Astronomy, 2016-present Senior Associate Dean for Graduate Education & Research, College of Arts & Science, 2015-present Harvie Branscomb Distinguished Professor, 2015-16 Professor of Physics and Astronomy, 2011-present Director, Vanderbilt Initiative in Data-intensive Astrophysics (VIDA), 2007-present Co-Director, Fisk-Vanderbilt Masters-to-PhD Bridge Program, 2004-15 Associate Professor of Physics and Astronomy, 2008-11 Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy, 2003-08 Fisk University Adjunct Professor of Physics, 2006-present University of Wisconsin—Madison NASA Hubble Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Astronomy, 2001-03 Area: Observational Studies of Low-Mass Star Formation Mentor: Robert D. Mathieu University of Wisconsin—Madison Assistant Director and Postdoctoral Fellow, NSF Graduate K-12 Teaching Fellows Program, 2000-01 Duties: Development of fellowship program, instructor for graduate course in science education research Mentor: Terrence Millar HONORS AND AWARDS HHMI Professor—2018- Research Corporation for Science Advancement SEED Award—2017 Research Corporation for Science Advancement TREE Award—2015 Diversity Visionary Award, Insight into Diversity—2015 1/25 Keivan G. -

© 2019 Kaisha Esty ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2019 Kaisha Esty ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “A CRUSADE AGAINST THE DESPOILER OF VIRTUE”: BLACK WOMEN, SEXUAL PURITY, AND THE GENDERED POLITICS OF THE NEGRO PROBLEM 1839-1920 by KAISHA ESTY A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the co-direction of Deborah Gray White and Mia Bay And approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey MAY 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “A Crusade Against the Despoiler of Virtue”: Black Women, Sexual Purity, and the Gendered Politics of the Negro Problem, 1839-1920 by KAISHA ESTY Dissertation Co-Directors: Deborah Gray White and Mia Bay “A Crusade Against the Despoiler of Virtue”: Black Women, Sexual Purity, and the Gendered Politics of the Negro Problem, 1839-1920 is a study of the activism of slave, poor, working-class and largely uneducated African American women around their sexuality. Drawing on slave narratives, ex-slave interviews, Civil War court-martials, Congressional testimonies, organizational minutes and conference proceedings, A Crusade takes an intersectional and subaltern approach to the era that has received extreme scholarly attention as the early women’s rights movement to understand the concerns of marginalized women around the sexualized topic of virtue. I argue that enslaved and free black women pioneered a women’s rights framework around sexual autonomy and consent through their radical engagement with the traditionally conservative and racially-exclusionary ideals of chastity and female virtue of the Victorian-era.