Ethnic Minorities Needs Assessment for Stoke-On-Trent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stoke on Trent Pharmacies NHS Code Pharmacy Name Address Post Code Tel

Stoke On Trent Pharmacies NHS code Pharmacy Name Address Post Code Tel. No FRF34 Angelway Chemist 283 Waterloo Road Cobridge ST6 3HL 01782 280037 FJ346 ASDA Pharmacy Scotia Road Tunstall ST6 6AT 01782 820010 FKX58 Birchill & Watson 20 Knypersley Road Norton in the Moors ST6 8HX 01782 534678 FQK77 Blurton Pharmacy 7 Ingestre Square Blurton ST3 3JT 01782 314408 FRQ52 Boots the Chemists 39 Trentham Rd Longton ST3 4DF 01782 319758 FKV79 Boots the Chemists Unit 10 Alexandra Retail Park Scotia Road, Tunstall ST6 6BE 01782 838341 FDF31 Boots the Chemists 25 Bennett Precinct Longton ST3 2HX 01782 313819 FDH31 Boots the Chemists 3/5 Upper Market Square Hanley ST1 1PZ 01782 213271 FFV80 Boots the Chemists 41 Queen Street Burslem ST6 3EH 01782 837576 FK255 Boots the Chemists Bentilee Neighbourhood Centre Dawlish Drive, Bentilee ST2 0EU 01782 212667 FL883 Boots the Chemists Unit 5 Festival Park Hanley ST1 5SJ 01782 284125 Burslem Pharmacy Lucie Wedgwood Health Centre Chapel Lane, Burslem ST6 2AB 01782 814197 FWL56 Eaton Park Pharmacy 2 Southall Way Eaton Park ST2 9LT 01782 215599 FDF74 Grahams Pharmacy 99 Ford Green Road Smallthorne ST6 1NT 01782 834094 FTV00 Hartshill Pharmacy Hartshill Primary Care Centre Ashwell Road, Hartshill ST4 6AT 01782 616601 FRQ98 Heron Cross Pharmacy 2-4 Duke Street Heron Cross ST4 3BL 01782 319204 FFP79 Lloyds Pharmacy Cobridge Community H/ Centre Elder Road, Cobridge ST6 2JN 01782 212673 FM588 Lloyds Pharmacy 128 Werrington Road Bucknall ST2 9AJ 01782 219830 FA530 Lloyds Pharmacy Fenton Health Centre Glebedale Road, Fenton -

NEWCASTLE- UNDER-LYME Stoke -On-Trent Hanley Burslem Tunstall

C O G AD O O G N U T A D A O T D U FEGG HAYES ROAD Fegg Hayes EN F N SH unnels T IEL R S D E D E I A O R C R P T LANE N OA A I C C D V H ON E R L E GT B O S O IN N EVA AD L A RIV N A G R AD RG R T E VE O RO E L C N O A E UE RIDG A E A R R N Y L D D U T UE P EN A N LO O S CDRIVE A AV O C D S IA V N V H GE N EL D E EE S H RO Line Houses O R E N IG AD ZC G H E L AD R L A O L C T H O R L J I R O O P L H S Y H T B A A R EA R H E R G K AN D D I D V U E L R U C E W E I B E CHEL GR S A L RD A N B O ER C A T T W H A E G G R ORD LISH T T S ORD RD R C O H OW H LE E SHELF E B RE E C N N N A E R A Y M CHEL ARDLEY DRO LA R R E EN W O T AD R A L IN R I O H D A H L A AZ D OA V N J A A I EL N R D Y H E E E D U R R A W G R AR LH W Y STR D W N M Talke L R D A R H Sandyford U 4 L O O I A O R H PL EA T T E A 3 OO FI E K G H ERSF D IC I ND T CROFTROAD D E S STA RN B A G E W H BA Whitfield A U Dunkirk O S B Parrot’s Drumble R Pits B E H C R L A S C O D Ravenscliffe O H O C D Valley R R Great Chell D U K A O OA Nature L E R A R L A S B A N I T D L E AK B L E E A D F D T PITL L O E E L R Y A O N O Y R O B Reserve E I R S N T G R R R N A R J O H A R Monks-Neil Park M O D D S Bathpool L E E L S A O ' EL’S E B D A P RI L A E ND D E N LEY A A L W N H A Pitts V I L Park Y H E A T 5 A T Little N Y R C 2 V A I E S Hill 7 E U OAD T M CORNHILL R S B 2 N S E E A N M SO U R Holly Wall O C N Chell E DR T S 7 E T D B A N OA A H Y 2 R Clanway S K R D W A U N I 5 Y O BA OAD G H W A B RINK T EYR O E G A WJO T SP C L A H U ES Sports K T N H O E R Y A H I N K S N W N B O N E A -

Mickey WIS 2009 England Registration Brochure 2.Pub

HHHEELLLLOOELLO E NNGGLLANANDDNGLAND, WWWEEE’’’RREERE B ACACKKACK!!! JJuunneeJune 888-8---14,1144,,14, 220000992009 WWISISWIS ### 554454 Wedgwood Museum Barlaston, England Celebrating 250 Years At Wedgwood, The 200th Birthday Of Charles Darwin And The New Wedgwood Museum 2009 marks the 250th anniversary of the founding of The Wedgwood Company. 2009 also marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Darwin and the 150th anniversary of the publication of his book, ‘On The Origin Of Species’. The great 19th Century naturalist had many links with Staffordshire, the Wedgwood Family, and there are many events being held there this year. The Wedgwood International Seminar is proud to hold it’s 54th Annual Seminar at the New Wedgwood Museum this year and would like to acknowledge the time and efforts put forth on our behalf by the Wedgwood Museum staff and in particular Mrs. Lynn Miller. WIS PROGRAM - WIS #54, June 8-14 - England * Monday - June 8, 2009 9:00 AM Bus Departs London Hotel To Moat House Hotel Stoke-On-Trent / Lunch On Your Own 3:00 PM Registration 3:00 PM, Moat House Hotel 5:30 PM Bus To Wedgwood Museum 6:00 PM President’s Reception @Wedgwood Museum-Meet Senior Members of the Company Including Museum Trustees, Museum Staff, Volunteers 7:00 PM Dinner & After Dinner Announcements Tuesday - June 9, 2009 8:45 AM Welcome: Earl Buckman, WIS President, George Stonier, President of the Museum, Gaye Blake Roberts, Museum Director 9:30 AM Kathy Niblet, Formerly of the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery “Studio Potters” 10:15 AM Lord Queesnberry -

March Auction Results

0800 090 2200 March Auction Results SOLD LOT ADDRESS PRICE 1 1 Crossley Road, Tunstall, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST6 7AJ £64,500 2 3 Ilkley Place, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire, ST5 6QP £82,000 3 78 Foley Street, Fenton, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST4 3DX £60,000 4 24 Riley Street North, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST6 4BJ Unsold 5 61 Hall o Shaw Street, Crewe, Cheshire CW1 4AE £79,000 6 39 Sovereign Lane, Ashley, Market Drayton, Shropshire, TF9 4LS Sold Prior 7 66 Seabridge Road, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire, ST5 2HT Unsold LOT 1 8 4 Bignall Hill, Bignall Hill, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST7 8QN Unsold 1 Crossley Road, Tunstall, Stoke- 9 4 Churchfields, Audlem, Cheshire, CW3 0AN Sold Prior on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST6 7AJ Jovial Foresters Inn, 17 Marsh Street South, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, 10 Unsold *Guide Price £44,000 Staffordshire, ST1 1JA SOLD £64,500 11 145 Hamil Road, Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST6 1AP £52,000 12 15 Melchett Crescent, Rudheath, Northwich, Cheshire, CW9 7EW £104,000 13 Land at St John Street, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST1 2HT £50,000 14 Land Adj. 70 St John Street, Hanley, Stoke -on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST1 2HU £13,000 15 Land Adj. 36 St John Street, Hanley, Stoke -on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST1 2HR £25,000 16 Land Adj. 65 Mynors Street, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST1 2DH £30,000 17 Land Adj. 18 Jervis Street, Hanley, Stoke -on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST1 2DH £20,500 18 19a Werburgh Drive, Trentham, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST4 8JT Unsold -

“Back to Its Former Glory!”

Newsletter of the Staffordshire Gardens and Parks Trust. Registered Charity No. 1013862. WINTER 2012 ISSUE No. 47 News Staffordshire Gardens & Parks Trust Published by the Staffordshire Gardens and Parks Trust. c/o South Staffordshire LETTER Council, Wolverhampton Road, Codsall, Staffordshire WV8 1PX. Tel: 01902 696000 “BACK TO ITS FORMER GLORY!” At half past four on the afternoon of August 30th, 1894, following a civic luncheon attended by 250 guests, the Mayor of Burslem, Alderman Spencer Lawton, led a procession seven thousand strong to Burslem Park behind a banner proclaiming “Success to Our Park”. After delivering a speech from the terrace, Cllr. Bowden, Chairman of the Baths and Parks Committee, with due ceremony unlocked the ornate gates with a silver-gilt key which he and his wife had donated. On June 23rd, 2012, a re-enactment took place to celebrate the re-opening of Burslem Park following the recent restoration. As part of the ceremony a copy of the original banner was carried through the park with a few thousand in attendance Various features of the new park were testimony to the munificence of local industrialists and the skill of local manufacturing: the two ornate terracotta fountains, were donated in memory of Arthur Wilkinson by his wife and daughters; gates, seats, shelters and drinking fountains made from terracotta were all donated by local industrialists. The origins of the park can be traced to the development of the pottery and mining industries which had transformed and despoiled the landscape of the area; by the end of the nineteenth century, Burslem had become a thriving Potteries town. -

Captain's Barn Farm, Weston Coyney, Staffs

Planning Application for the Winning and Working of Sand And Aggregate at Captain's Barn Farm, Weston Coyney, Staffs. Envi ron mental Statement CAPTAIN'S BARN FARM, WESTON COYNEY, STAFFOBDSHIRE ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT CONTENTS CHAPTER Page Non-Technical Summary 1 1.0 Introduction 12 2.O The Requirement for Environmental lmpact Assessment 12 3.0 Site Locatlon and Description 14 4.0 Geology 15 5.0 Reserues 16 6.0 Extraction ol Sand and Aggregate 17 7.0 Alternative Sites 19 8.0 Environmental I mpact Assessment 20 8.1 Nolse - Noise Consultancy Associates 21 8.2 Dust - Halletec Associates Ltd 23 8.3 Agrlcultural Land Glassification - Land Hesearch Assoclates 26 8.4 Landscape & Visual lmpact - Bright & Assts 28 8.5 Ecology - Eco Tech 33 8.6 Archaeology - Marches Archaeology 38 8.7 Traftic - L. Lammas 40 8.0 Public Rights of Way 43 8.9 Hydrogeology - Halletec Associatesi/ Wrc 43 8,10 Effects of Assoclatlon with other forms ol Development 46 8,11 Conclusions 46 DRAWINGS Locatlon Plan 2MH1 Site Plan 244iz2 Schematic Layout of Processing Nea244l2l3 APPENDICES Appendix 1 Scoping Opinion Staftordshire County Council Appendix 2 Noise Report Noise Consultancy Services Appendlx 3 Agricultural Land Classification Land Research Associates Appendix 4 Landscape Assessment Bright & Associates Appendix 5 Ecological Assessment Eco Tech Appendix 6 Archaeological Beport Marches Archaeology Appendlx 7 Traffic & Highways Study Leslie E. Lammas Appendix 8 Hydrogeology & Hydrology Report Halletec Assoclates o o Non Technical Summary CAPTAIN'S BARN FARM, WESTON COYNEY, STAFFORDSHIRE NON.TECHNICAL SUMMARY Contents Sectlon Page 1 Introduction t 2 Need 1 3 Description of the Proposed Development 3 4 Noise c c Dusl 5 6 Agrlcullural Land Classification 5 7 Landscape 6 8 Ecology 7 I Archaeology I 10 Trafflc and Highways I 11 Public Rights ol Way 10 12 Hydrology and Hydrogeology 10 13 Elfects of Assoclatlon wlth other forms of 11 Development 14 Summary 11 C.E. -

Inspection Report Goldenhill, St Joseph's

INSPECTION REPORT GOLDENHILL, ST JOSEPH’S CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOL Goldenhill LEA area: Stoke-on-Trent Unique reference number: 124314 Headteacher: Mr J Tierney Reporting inspector: David Penney 23039 Dates of inspection: 9th – 12th July 2001 Inspection number: 213414 Full inspection carried out under section 10 of the School Inspections Act 1996 © Crown copyright 2001 This report may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that all extracts quoted are reproduced verbatim without adaptation and on condition that the source and date thereof are stated. Further copies of this report are obtainable from the school. Under the School Inspections Act 1996, the school must provide a copy of this report and/or its summary free of charge to certain categories of people. A charge not exceeding the full cost of reproduction may be made for any other copies supplied. INFORMATION ABOUT THE SCHOOL Type of school: Primary School category: Voluntary Aided Age range of pupils: 3 – 11 years Gender of pupils: Mixed School address: Mobberley Road Goldenhill Stoke-on-Trent Staffordshire Postcode: ST6 5RN Telephone number: (01782) 235393 Fax number: (01782) 235394 Appropriate authority: The Governing Body Name of chair of governors: Mrs Christine Hulme Date of previous inspection: May 1999 Goldenhill, St Joseph’s RC Primary School - 1 INFORMATION ABOUT THE INSPECTION TEAM Subject Aspect Team members responsibilities responsibilities 23039 David Penney Registered inspector Equal opportunities What sort of school is -

Southern Stoke ARF

Southern Stoke ARF RENEW November 2007 (Final Draft) www.gvagrimley.co.uk RENEW Contents CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................1 2. ARF IN CONTEXT ....................................................................................................10 3. VISION AND OBJECTIVES .....................................................................................44 4. STRATEGY AND PROPOSALS ..............................................................................52 5. DELIVERING LOCAL BENEFIT ..............................................................................84 6. DELIVERY STRATEGY............................................................................................92 November 2007 RENEW Southern Stoke ARF 1. INTRODUCTION Purpose of ARF 1.1 GVA Grimley LLP, taking the lead role in a wider consortium of consultants including a number of specialisms, have been commission by RENEW North Staffordshire (RENEW) to produce an Area Regeneration Framework (ARF) for the Southern Stoke area. 1.2 The ARF sets out the evidence base behind and strategy for a comprehensive programme of intervention to secure housing market renewal and sustainable neighbourhoods. It sets out a schedule of interventions to be delivered by RENEW and its partners, as part of an appropriate phasing strategy for the area. 1.3 The ARF is a housing market focused strategic spatial framework that sets out a vision for the future regeneration of the Southern Stoke area. -

Stoking Employment

Stoking Employment Local Sustainable Transport Fund Tranche 2 Application Form Local Sustainable Transport Fund - Application Form Applicant Information Local transport authority name(s)*: Stoke-on-Trent City Council Senior Responsible Owner name and position: Pete Price: Assistant Director – Technical Services, City Renewal Directorate Bid Manager name and position: John Nichol: Strategic Manager Transportation and Engineering Contact telephone number: 01782 236178 Email address: [email protected] [email protected] Postal address: Civic Centre, Glebe Street, Stoke-on-Trent, ST4 1HH Website address for published bid: www.stoke.gov.uk/ltp Section A – Project description and funding profile A1. Project Name. Stoking Employment A2. Headline description: This package of sustainable transport interventions will improve access to three major employment sites and will significantly enhance the local economy through: • improved connectivity to jobs from areas of deprivation, resulting in better opportunities for employment of local residents; • helping to unlock 10,000 jobs; • an increased pool of labour available to businesses on the key employment sites. The package also includes measures specifically aimed at reducing levels of CO2 by: • increasing the number of employees travelling to the sites by sustainable modes; • providing better bus measures; increased travel planning, marketing and availability of information and implementation of walking / cycling initiatives. A3. Geographical area: Figure 1: Location plan Figure 1 shows the spatial area covered by this application. Stoke-on- Trent is a large city, with a population of approximately 239,000 people. It lies in an enviable strategic location, at the heart of the country, between the West Midlands and North West conurbations. -

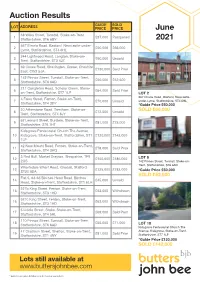

Auction Results June 2021

Auction Results GUIDE SOLD LOT ADDRESS PRICE PRICE June 38 Wilks Street, Tunstall, Stoke-on-Trent, 1 £37,000 Postponed Staffordshire, ST6 6BY 2021 567 Etruria Road, Basford, Newcastle-under- 2 £50,000 £66,000 Lyme, Staffordshire, ST4 6HL 244 Lightwood Road, Longton, Stoke-on- 3 £90,000 Unsold Trent, Staffordshire, ST3 4JZ 69 Crewe Road, Shavington, Crewe, Cheshire 4 £130,000 Sold Prior East, CW2 5JA 142 Pinnox Street, Tunstall, Stoke-on-Trent, 5 £50,000 £52,500 Staffordshire, ST6 6AD 211 Congleton Road, Scholar Green, Stoke- 6 £64,000 Sold Prior on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST7 1LP LOT 2 567 Etruria Road, Basford, Newcastle- 4 Foley Street, Fenton, Stoke-on-Trent, 7 £70,000 Unsold under-Lyme, Staffordshire, ST4 6HL Staffordshire, ST4 3DY *Guide Price £50,000 20 Atherstone Road, Trentham, Stoke-on- 8 £72,500 Unsold SOLD £66,000 Trent, Staffordshire, ST4 8JY 62 Leonard Street, Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, 9 £81,000 £75,000 Staffordshire, ST6 1HT Kidsgrove Pentecostal Church The Avenue, 10 Kidsgrove, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST7 £120,000 £142,000 1LP 42 New Mount Road, Fenton, Stoke-on-Trent, 11 £78,000 Sold Prior Staffordshire, ST4 3HQ 3 Red Bull, Market Drayton, Shropshire, TF9 12 £150,000 £186,000 LOT 5 2QS 142 Pinnox Street, Tunstall, Stoke-on- Trent, Staffordshire, ST6 6AD Wharfedale Wharf Road, Gnosall, Stafford 13 £125,000 £182,000 ST20 0DA *Guide Price £50,000 Flat 5, 63-65 Birches Head Road, Birches SOLD £52,500 14 £45,000 Unsold Head, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ST1 6LH 527b King Street, Fenton, Stoke-on-Trent, 15 £63,000 Withdrawn -

BBC Voices Recordings: Bentilee, Stoke-On-Trent

BBC VOICES RECORDINGS http://sounds.bl.uk Title: Bentilee, Stoke-on-Trent Shelfmark: C1190/32/01 Recording date: 24.03.2005 Speakers: Ball, Amanda, b. 1966 Stoke-on-Trent; female; nursery nurse (father b. Stoke-on-Trent, security; mother b. Stoke-on-Trent, housewife) Ball, Daniel, b. 1922 Tunstall; male (father b. Hanley, steel-worker; mother b. Penkhull, canal boat worker) Ball, Joan, b. 1924 female (father b. Ironbridge, labourer; mother b. domestic service) Ball, Philip Andrew, b. 1960 Stoke-on-Trent; male; manufacturing (father b. Tunstall, kiln worker; mother b. Werrington, pottery worker) The interviewees represent three generations of a Stoke-on-Trent family. PLEASE NOTE: this recording is still awaiting full linguistic description (i.e. phonological, grammatical and spontaneous lexical items). A summary of the specific lexis elicited by the interviewer is given below. ELICITED LEXIS ○ see English Dialect Dictionary (1898-1905) ∆ see New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (2006) ◊ see Green’s Dictionary of Slang (2010) ♥ see Dictionary of Contemporary Slang (2014) # see Dictionary of North East Dialect (2011) ⌂ no previous source (with this sense) identified pleased pleased; mint◊ (suggested by interviewer, used as term of approval); cool (used as term of approval); wicked (initially misunderstood when used by daughter as term of approval); happy; glad tired knackered; sleepy; drowsy http://sounds.bl.uk Page 1 of 3 BBC Voices Recordings unwell ill; under the weather (suggested by interviewer, used occasionally); -

Magazine: 50P Each Or £5 Per Year PAGE 2 CAVERSWALL, DILHORNE & WESTON COYNEY POST

Magazine: 50p each or £5 per year PAGE 2 CAVERSWALL, DILHORNE & WESTON COYNEY POST “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”. DECEMBER These words are quoted from Sunday 6 December “A tale of two cities” by Charles 2nd Sunday of Advent Dickens. These words are true Malachi 3.1-4 & Luke 3.1-6 today in view of our financial Sunday 13 December difficulties in our country where businesses are 3rd Sunday of Advent struggling, and jobs in their hundreds, including Zephaniah 3.14-20 & Luke 3.7-18 the steel industry, are being lost each week. Sunday 20 December We are seeing appalling media news each 4th Sunday of Advent day showing the terrible suffering of the refu- Micah 5.2-5a & Luke 1.39-55 gees who in desperation are fleeing the war in Christmas Eve (Thurs 24th) Syria to come to Europe. They are words that 2 Samuel 7.1-5, 8-11, 16 were true in Dickens’ day, and in the French Luke 1.67-79 Revolution that the book is about and indeed Christmas Day (Fri 25th) in the days of Mary and Joseph when Jesus Isaiah 52.7-10 & Luke 2.1-20 was born in that stable at Bethlehem and they Sunday 27 December fled from the rage of King Herod to be refu- 1st Sunday of Christmas gees in Egypt. 1 Samuel 2.18-20,26 & Luke 2.41-52 But if that is the bad news, what is the good JANUARY news? At Christmas we thank God as we cele- brate the most wonderful good news this world Sunday 3 January has ever known.