Investigating Conflict in a Forest-Agriculture Fringe in Southern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minor Mineral Quarry Details: Ranni Taluk, Pathanamthitta District

Minor Mineral Quarry details: Ranni Taluk, Pathanamthitta District Sl.No Code Mineral Rocktype Village Locality Owner Operator 1 94 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Athikayam Chembanmudi Tomy Abraham, Manimalethu, Vechoochira , Ranni, Tomy Abraham, Manimalethu, Vechoochira , Ranni, Kuriakose Sabu, Vadakkeveli kizhakkethilaya kavumkal, Kuriakose Sabu, Vadakkeveli kizhakkethilaya kavumkal, 2 444 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Athikayam Chembanoly Angadi P.O., Ranni Angadi P.O., Ranni Kuriakose Sabu, Vadakkevila kizhakkethilaya, Kuriakose Sabu, Vadakkevila kizhakkethilaya, kavumkal, 3 445 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Athikayam Chembanoly kavumkal, Angadi P.O., Ranni. Angadi P.O., Ranni. Aju Thomas, Kannankuzhayathu Puthenbunglow, Aju Thomas, Kannankuzhayathu Puthenbunglow, 4 506 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Athikayam Unnathani Thottamon, Konni Thottamon, Konni 5 307 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Cherukole Santhamaniyamma, Pochaparambil, Cherukole P.O. Chellappan, Parakkanivila, Nattalam P.O., Kanyakumari 6 315 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Cherukole Kuttoor Sainudeen, Chakkala purayidam, Naranganam P.O. Sainudeen, Chakkala purayidam, Naranganam P.O. 7 316 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Cherukole Kuttoor Chacko, Kavumkal, Kuttoor P.O. Chacko, Kavumkal, uttoor P.O. 8 324 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Cherukole Nayikkan para Revenue, PIP Pamba Irrigation Project Pampini/Panniyar 9 374 Granite(Building Stone) Migmatite Chittar-Seethathode Varghese P.V., Parampeth, Chittar p.O. Prasannan, Angamoozhy, -

Lessons from Periyar Tiger Reserve in Kerala State, India

TROPICS Vol. 17 (2) Issued April 30, 2008 Implementation process of India Ecodevelopment Project and the sustainability: Lessons from Periyar Tiger Reserve in Kerala State, India * Ellyn K. DAMAYANTI and Misa MASUDA Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Japan *Corresponding author: Tel: +81−29−853−4610/Fax: +81−29−853−4761, E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Protected areas in developing involvement of local people, and it has been applied countries have been in a dilemma between to various parts of developing countries with similar biodiversity conservation and improvement of situations. Based on the varied local conditions, ICDPs local livelihood. The study aims to examine the have been applied from small to large-scale with different sustainability of India Ecodevelopment Project (IEP) degrees of people’s involvement and various types of in Periyar Tiger Reserve (PTR), Kerala, through funding mechanisms. analyzing kinds of financial mechanisms that However, Wells et al. (1992) who studied the initial were provided by the project, how IEP had been stage of ICDP implementation in 23 projects in Africa, implemented, and what kind of changes emerged Asia and Latin America concluded that even under the in the behaviors and perceptions of local people. best conditions ICDPs could play only a modest role in The results of secondary data and interviews with mitigating the powerful forces causing environmental key informants revealed that organizing people into degradation. Through lessons learned from Southeast Ecodevelopment Committees (EDCs) in the IEP Asia, MacKinnon and Wardojo (2001) suggested the implementation has resulted positive impacts in factors for the success of ICDP, which can be summarized terms of reducing offences and initiating regular as: 1) clear demarcation of the area, 2) capacity of involvement of local people in protection activities. -

District Census Handbook

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-B SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. Contents Pages 1 Foreword 1 2 Preface 3 3 Acknowledgement 5 4 History and Scope of the District Census Handbook 7 5 Brief History of the District 9 6 Administrative Setup 12 7 District Highlights - 2011 Census 14 8 Important Statistics 16 9 Section - I Primary Census Abstract (PCA) (i) Brief note on Primary Census Abstract 20 (ii) District Primary Census Abstract 25 Appendix to District Primary Census Abstract Total, Scheduled Castes and (iii) 33 Scheduled Tribes Population - Urban Block wise (iv) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes (SC) 41 (v) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Tribes (ST) 49 (vi) Sub-District Primary Census Abstract Village/Town wise 57 (vii) Urban PCA-Town wise Primary Census Abstract 89 Gram Panchayat Primary Census Abstract-C.D. -

Analysing Lee's Hypotheses of Migration in the Context of Malabar

International Journal of Research in Geography (IJRG) Volume 4, Issue 1, 2018, PP 1-8 ISSN 2454-8685 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-8685.0401001 www.arcjournals.org Analysing Lee’s Hypotheses of Migration in the Context of Malabar Migration: A Case Study of Taliparamba Block, Kannur District Surabhi Rani 1 Dept.of Geography, Kannur University Payyanur Campus, Edat. P.O ,Payyanur, Kannur, Kerala Abstract: Human Migration is considered as one of the important demographic process which has manifold effect on the society as well as to the individuals, apart from the other population dynamics of fertility and mortality. Several approaches dealing with migration has evolved the concepts related to the push and pull factors causing migration. Malabar Migration is a historical phenomenon of internal migration, in which massive exodus took place in the vast jungles of Malabar concentrating with similar socio-cultural-economic group of people. Various factors related to social, cultural, demographical and economical aspects initiated the migration from erstwhile Travancore to erstwhile Malabar district. The present preliminary study tries to focus over such factors associated with Malabar Migration in Taliparamba block of Kannur district (Kerala).This study is based on the primary survey of the study area and further supplemented with other secondary materials. Keywords: migration, push and pull factors, Travancore, Malabar 1. INTRODUCTION Human migration is one of the few truly interdisciplinary fields of research of social processes which has widespread consequences for both, individuals and the society. It is a sort of geographical or spatial mobility of people with change in their place of residence and socio-cultural environment. -

Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church SABHA PRATHINIDHI MANDALAM 2017 - 2020 Address List of Mandalam Members Report Date: 27/07/2017 DIOCESE - ALL Page 1 of 25

Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church SABHA PRATHINIDHI MANDALAM 2017 - 2020 Address List of Mandalam Members Report Date: 27/07/2017 DIOCESE - ALL Page 1 of 25 C001 (NIRANAM - MARAMON DIOCESE) C002 (NIRANAM - MARAMON DIOCESE) C003 (RANNI - NILACKAL DIOCESE) MOST REV. DR. PHILIPOSE MAR MOST REV. DR. JOSEPH MAR THOMA RT. REV. GEEVARGHESE MAR CHRYSOSTOM VALIYA METROPOLITAN METROPOLITAN ATHANASIUS SUFFRAGAN - POOLATHEEN METROPOLITAN JUBILEE HOME, S C S CAMPUS SUFFRAGAN METROPOLITAN MARAMON PO TIRUVALLA PO T M A M, MAR THOMA CENTRE KERALA - 689549 KERALA - 689101 MANDIRAM PO, RANNY 0468-2211212/2211210 0469-2630313,2601210 KERALA - 689672 C004 (MUMBAI DIOCESE) C005 (KOTTARAKARA - PUNALUR C006 (THIRUVANANTHAPURAM - RT. REV. DR. GEEVARGHESE MAR DIOCESE) KOLLAM DIOCESE) THEODOSIUS EPISCOPA RT. REV. DR. EUYAKIM MAR COORILOS RT. REV. JOSEPH MAR BARNABAS MAR THOMA CENTRE, EPISCOPA EPISCOPA SECTOR 10-A,PLOT #18, NAVI MUMBAI OORSALEM ARAMANA,66 KV - VASHI PO SUBSTATION ROAD, MAR THOMA CENTRE, MAHARASHTRA - 400703 PRASANTHI NAGAR, KIZHAKKEKKARA, MANNANTHALA PO, TVPM 022 27669484(O)/27657141(P)/ KOTTARAKARA H O PO KERALA - 695015 C007 (CHENGANNUR - MAVELIKKARA C008 (NORTH AMERICA - EUROPE C009 (ADOOR DIOCESE) DIOCESE) DIOCESE) RT. REV. DR. ABRAHAM MAR PAULOS RT. REV. THOMAS MAR TIMOTHEOS RT. REV. DR. ISAAC MAR PHILOXENOS EPISCOPA EPISCOPA EPISCOPA - - SINAI M.T. CENTRE,2320 S.MERRICK AVE, HERMON ARAMANA, OLIVET ARAMANA, THITTAMEL, MERRICK, NEW YORK 11566 U.S.A ADOOR PO CHENGANNUR PO 001 516 377 3311/ 001 516 377 3322(F) KERALA - 691523 KERALA - 689121 [email protected] 04734 228240(O)/ 229130(P) C010 (CHENNAI - BANGALORE DIOCESE) C011 (DELHI DIOCESE) C012 (KUNNAMKULAM - MALABAR RT. REV. DR. MATHEWS MAR MAKARIOS RT. -

Marxist Praxis: Communist Experience in Kerala: 1957-2011

MARXIST PRAXIS: COMMUNIST EXPERIENCE IN KERALA: 1957-2011 E.K. SANTHA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SIKKIM UNIVERSITY GANGTOK-737102 November 2016 To my Amma & Achan... ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the outset, let me express my deep gratitude to Dr. Vijay Kumar Thangellapali for his guidance and supervision of my thesis. I acknowledge the help rendered by the staff of various libraries- Archives on Contemporary History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, C. Achutha Menon Study and Research Centre, Appan Thampuran Smaraka Vayanasala, AKG Centre for Research and Studies, and C Unniraja Smaraka Library. I express my gratitude to the staff at The Hindu archives and Vibha in particular for her immense help. I express my gratitude to people – belong to various shades of the Left - who shared their experience that gave me a lot of insights. I also acknowledge my long association with my teachers at Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur and my friends there. I express my gratitude to my friends, Deep, Granthana, Kachyo, Manu, Noorbanu, Rajworshi and Samten for sharing their thoughts and for being with me in difficult times. I specially thank Ugen for his kindness and he was always there to help; and Biplove for taking the trouble of going through the draft intensely and giving valuable comments. I thank my friends in the M.A. History (batch 2015-17) and MPhil/PhD scholars at the History Department, S.U for the fun we had together, notwithstanding the generation gap. I express my deep gratitude to my mother P.B. -

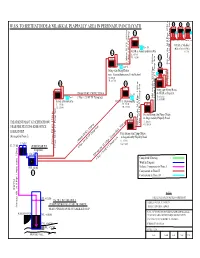

W.S.S. to Seethathode & Nilakkal Plappally Area in Perunadu Panchayath

R6 R7 R8 W.S.S. TO SEETHATHODE & NILAKKAL PLAPPALLY AREA IN PERUNADU PANCHAYATH 20 LL 20 LL 20 LL R3 Zone VI Zone VII Zone VIII 0.3 LL (P) Interconnection 500 mm M.S Pipe, 10 mm thick, 1800 m OHSR at Nilakkal Zone III (Highest Point in PM is R2 GLSR at Gurumandiram (R6) 417.53) IL. 455.00 0.5 LL GL. 452.00 R5 100mm DI K9, 2000 m 2 Nos. 5 HP CF Pump S3 500 mm dia. M.S Pipe, 8250 m 3 Nos. 110 HP VT Pump Sets Zone II Sump cum Pump House 3.5 LL near Gurunathanmannu Tribal School Zone V IL. 290.00 6.0 LL GL. 287.00 3 Nos. 2 HP R1 R4 CF Pump Sets 3.0 LL (P) 3.0 LL Sump cum Pump House 150 mm DI K9 CWPM, 5200 m Zone IV & OHSR at Plapally 500 mm dia. M.S Pipe, 1900 m IL of Sump : Zone I 2 Nos. 12.5 HP CF Pump Sets S2 3 Nos. 175 HP VT Pump Sets IL of OHSR Sump at Kottakuzhy GLSR at Aliyanmukku IL. 175.00 IL. 178.00 6.0 LL GL. 172.00 GL. 175.00 S1 Second Sump cum Pump House in Angamoozhy Plapally Road TREATMENT PLANT AT SEETHATHODU 6.0 LL IL. 266.00 GL. 263.00 500 mm dia. M.S Pipe, 2100 m NEAR FIRE STATION& KSEB OFFICE 3 Nos. 175 HP VT Pump Sets KAKKAD HEP First Sump cum Pump House (Arranged in Phase I) in Angamoozhy Plapally Road 200mm DI K9, 3700 m IL. -

Details of UCUP Dividend and Shares

Details of Unclaimed & unpaid divided and shares to be transferred First Name Final Address Folio Number of Unclaimed No. of Securities Dividend Amount shares DOOR NO 36831A 12,SRIRANGA NIVAS,ANJANEYA LAYOUT A G KANTHARAJ SETTY KARNATAKA DAVANGARE 577004 IN302148 10239488 50.00 50 DOOR NO 36831A 12,SRIRANGA NIVAS,ANJANEYA LAYOUT A G KANTHARAJ SETTY KARNATAKA DAVANGARE 577004 IN302148 10239488 100.00 50 CHOLAMANDALAM SECURITIES LTD,PARRY HOUSE, 2ND A M M ARUNACHALAM & SONS FLOOR,,NO.2, NSC BOSE ROAD, PARRYS TAMIL NADU CHENNAI PRIVATE LTD 600001 IN300572 10002251 600.00 400 14 WEST CHETTY STREET,SOUTH AVANI MOOLA ST, TAMIL NADU A MANGAIYARKARASI MADURAI 625011 1202990000251522 30.00 15 A PRAMOD KUMAR 2,STONE LINK AVENUE,R A PURAM TAMIL NADU CHENNAI 600028 IN302679 33196844 150.00 100 A PUSHPAM 24/1,TOOVIPURAM,3RD STREET TAMIL NADU TUTICORIN 628003 IN300394 13917320 1.00 1 A-5/6 ADITYA HOMES,RD NO 7 EXTN, SONARI,JAMSHEDPUR A. P. SANJAYAN JHARKHAND EAST SINGHBHUM 831011 IN300450 10322321 15.00 10 A/P SHRIRAM NAGAR,LASALGAON,TAL NIPHAD MAHARASHTRA ABHIJIT PRAKASH BIDWAI NASHIK 422306 IN302236 10599958 1.00 1 KOTAK SECURITIES LTD(PMS),BAKHTAWAR 1ST FLOOR,229 ABHIMANYU MUNJAL NARIMAN POINT MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400021 IN300214 10439922 91.50 61 PUTHENPARAMBIL HOUSE,KADAPRA P O,KUMBANAD KERALA ABRAHAM P JOHN PATHANAMTHITTA 689547 IN300239 10574483 15.00 10 THUNDIL KIZHAKKETHIL HOUSE,NANGIARKULANGARA P O,HARIPAD ABY SAM VARGHESE KERALA ALAPPUZHA 690513 IN300239 11294176 20.00 10 84-A, MITTAL COURT,224, NARIMAN POINT, MAHARASHTRA ADVITIYA FABRICS PVT.LTD. MUMBAI 400021 IN300319 10008400 2250.00 1500 AJAY KAROL H NO 632/16A,, 121001 1202990000447144 34.00 17 5/542, SATYA PREMI NAGAR,BARABANKI, UTTAR PRADESH AJAY KUMAR DIXIT BARABANKI 225001 IN300476 40388062 10.00 10 AJAY NURSING HOME,DALHOUSIE ROAD, PUNJAB GURDASPUR AJAY MAHAJAN 145001 IN301436 10517916 50.00 50 First Name Final Address Folio Number of Unclaimed No. -

Live Hospitals on E-RUPI

Acquirer Bank/Merchant Sr No ID Business Name Address District/City Phone Number Zip Code HEALTH CARE HOSPITAL AND 03 ward no 11patel mohalla pithampur03 ward no HEMANT PATEL, 9289911111, SBI 1 DIAGNOSTIC CENTER 11patel mohalla pithampur,mohalla,pithampur BHOPAL, BHOPAL [email protected] 462023 2 SBI JAGDHAN HEALTH CARE PVT LTD 168 G T ROAD SOUTH SHIBPUR,HOWRAH,WEST HOWRAH, VIVEK ARJARIYA, 8282909039, 711102 NH2 BAMCHANBAIPUR, JOTROM,East burdwan,WEST BARDHAMAN, Himanshu Sekhar Kamley, 9434002169, SBI 3 Sharanya Multispeciality Hospital BENGAL KOLKATA [email protected] 713101 Immon Kalyan Sarani, Sector IIC,,Bidhannagar, BARDHAMAN, Arif Perwez, 9933687816, SBI 4 Mission Hospital Durgapur, West Bengal,WEST BENGAL KOLKATA [email protected] 713212 5 SBI MANORAMA HOSPITEX PVT LTD 2 R B N N MUKHERJEE ROAD,RANAGHAT NADIA,WEST NADIA, KOLKATA RAJESH SINHA, 8373091208, 741201 SONOSCAN HEALTHCARE PRIVATE 44, CIT Rd, Beniapukur, Kolkata, West Bengal KOLKATA, Subhra MONDAL, 9775996048, SBI 6 LIMITED 700014,KOLKATA,west bengal KOLKATA [email protected] 700014 P/1-1, Jadavpur Station Rd, Jadavpur University SBI KPC MEDICAL COLLEGE AND Campus Area,Jadavpur, Kolkata, West Bengal KOLKATA, Accounts manager, 9822334656, 7 HOSPITAL 700032,kolkata,West Bengal KOLKATA [email protected] 700032 MIOT HOSPITALS PRIVATE LIMITED, NO.4/112 MOUNT Tamil Selvi, 9841615433, SBI POONAMALLEE ROAD, MANAPAKKAM, CHENNAI - KANCHIPURAM, [email protected],accounts1 8 MIOT HOSPITALS PVT LTD 600 089,MANAPAKKAM,CHENNAI CHENNAI @miotinternational.com -

2004-05 - Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2004-05 - Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010105768 Asha S R Keezhay Kunnathu Veedu,Irayam Codu,Cheriyakonni 0 F R Textile Business Sector 52632 44737 21/05/2004 2 010105770 Aswathy Sarath Tc/ 24/1074,Y.M.R Jn., Nandancodu,Kowdiar 0 F U Bakery Unit Business Sector 52632 44737 21/05/2004 2 010106290 Beena Kanjiramninna Veedu,Chowwera,Chowara Trivandrum 0 F R Readymade Business Sector 52632 44737 26/04/2004 2 010106299 Binu Kumar B Kunnuvila Veedu,Thozhukkal,Neyyattinkara 0 M U Dtp Centre Service Sector 52632 44737 22/04/2004 2 1 010106426 Satheesan Poovan Veedu, Tc 11/1823,Mavarthalakonam,Nalanchira 0 M U Cement Business Business Sector 52632 44737 19/04/2004 1 2 010106429 Chandrika Charuninnaveedu,Puthenkada,Thiruppuram 0 F R Copra Unit Business Sector 15789 13421 22/04/2004 1 3 010106430 Saji Shaji Bhavan,Mottamoola,Veeranakavu 0 M R Provision Store Business Sector 52632 44737 22/04/2004 1 4 010106431 Anil Kumar Varuvilakathu Pankaja Mandiram,Ooruttukala,Neyyattinkara 0 M R Timber Business Business Sector 52632 44737 22/04/2004 1 5 010106432 Satheesh Panavilacode Thekkarikath Veedu,Mullur,Mullur 0 M R Ready Made Garments Business Sector 52632 44737 22/04/2004 1 6 010106433 Raveendran R.S.Bhavan,Manthara,Perumpazhuthur 0 C M U Provision Store Business Sector 52632 44737 22/04/2004 1 010106433 Raveendran R.S.Bhavan,Manthara,Perumpazhuthur -

1913 , 05/08/2019 Class 38 2987043 17/06/2015 Address for Service In

Trade Marks Journal No: 1913 , 05/08/2019 Class 38 2987043 17/06/2015 ZEE MEDIA CORPORATION LIMITED B-10, LAWRENCE ROAD, INDUSTRIAL AREA, NEW DELHI 110035 SERVICE PROVIDER Address for service in India/Attorney address: VIDHANI ASSOCIATES 11/12, UGF, P.N. BANK BUILDING, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI-8 Proposed to be Used DELHI TELECOMMUNICATION; CABLE TELEVISION BROADCASTING; COMMUNICATIONS BY FIBER OPTIC NETWORKS; COMPUTER AIDED TRANSMISSION OF MESSAGES. IMAGES & SOUNDS; COMPUTER TERMINALS (COMMUNICATIONS SERVICES); NEWS AGENCIES; PROVIDING TELECOMMUNICATION CHANNELS FOR TELESHOPPING SERVICES; PROVIDING TELECOMMUNICATIONS CONNECTIONS TO A GLOBAL COMPUTER NETWORK; TELEVISION & RADIO BROADCASTING; RENTAL OF TELECOMMUNICATION EQUIPMENT; TELECOMMUNICATIONS ROUTING & JUNCTION SERVICES; TELEVISION BROADCASTING; TRANSMISSION OF MESSAGES & IMAGES REGISTRATION OF THIS TRADE MARK SHALL GIVE NO RIGHT TO THE EXCLUSIVE USE OF THE.DELHI. 6435 Trade Marks Journal No: 1913 , 05/08/2019 Class 38 3007334 10/07/2015 NEWS DNN PRIVATE LIMITED trading as ;NEWS DNN PRIVATE LIMITED 166/2, DR. SHAM SINGH ROAD, CIVIL LINES, LUDHIANA-141001 (PB.) SERVICES Address for service in India/Attorney address: MAHTTA & CO 43-B/3, UDHAM SINGH NAGAR, LUDHIANA. 141001 (PUNJAB) Used Since :16/06/2015 DELHI Television and Broadcasting Services; Entertainment and Religious T.V. Channels; News Broadcasting Services. 6436 Trade Marks Journal No: 1913 , 05/08/2019 Class 38 3050566 09/09/2015 DISH TV INDIA LTD. ESSEL HOUSE,B-10 LAWRENCE ROAD INDUSTRIAL AREA NEW DELHI-35 SERVICE PROVIDER -

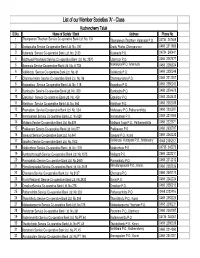

List of Our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No

List of our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No. Name of Society / Bank Address Phone No. 1 Thumpamon Thazham Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 134 Thumpamon Thazham, Kulanada P.O. 04734 267609 2 Arattupuzha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 787 Arattu Puzha, Chengannoor 0468 2317865 3 Kulanada Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2133 Kulanada P.O. 04734 260441 4 Mezhuveli Panchayat Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2570 Ullannoor P.O. 0468 2287477 5 Aranmula Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. A 703 Nalkalickal P.O. Aranmula 0468 2286324 6 Vallikkodu Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 61 Vallikkodu P.O. 0468 2350249 7 Chenneerkkara Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 96 Chenneerkkara P.O. 0468 2212307 8 Kaippattoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 115 Kaipattoor P.O. 0468 2350242 9 Kumbazha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 330 Kumbazha P.O. 0468 2334678 10 Elakolloor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 459 Elakolloor P.O. 0468 2342438 11 Elanthoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 460 Elanthoor P.O. 0468 2362039 12 Pramadom Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 534 Mallassery P.O.,Pathanamthitta 0468 2335597 13 Naranganam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.628 Naranganam P.O. 0468 2216506 14 Mylapra Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.639 Mailapra Town P.O., Pathanamthitta 0468 2222671 15 Prakkanam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.677 Prakkanam P.O. 0468 2630787 16 Vakayar Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.847 Vakayar P.O., Konni 0468 2342232 17 Janatha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.1042 Vallikkodu -Kottayam P.O., Mallassery 0468 2305212 18 Mekkozhoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd.