Kerouac Beat Painting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Fast Move Or IFINAL

1 One Fast Move or I’m Gone: Kerouac’s Big Sur. Dir. Curt Worden. Perfs. Joyce Johnson, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Carolyn Cassady, John Ventimiglia, Tom Waits, Sam Shepard, Patti Smith, Bill Morgan, Brenda Knight, and others. DVD. Kerouacfilms, 2008. $29.98 Reviewed by Tom Pynn If you think Kerouac found salvation on the road . you don’t know jack. Since 1986 we’ve had a handful of films about Jack Kerouac and the “beat generation” that have appealed to a general audience. Documentaries such as John Antonelli’s Kerouac (1986), Lerner and MacAdams’ What Happened to Kerouac? (1986), and, more recently, Chuck Workman’s The Source (2000), however, fail to get to the heart of the matter concerning the works themselves, but have instead tended to focus on the lives of the artists. This conceptual failure has tended to perpetuate the cult(s) of personality of particular members, mostly the men, while obscuring the deeper significance of the works and the place in American arts and letters of these important writers and artists. Beat Studies scholars have therefore faced difficult challenges in convincing the public and academia of the importance of the literature and elevating Kerouac et al. beyond mere fodder for Euro-American teenage male fantasy, which is especially true of the work of Jack Kerouac, the so-called “King of the Beats.” Curt Worden and Jim Sampas’ One Fast Move or I’m Gone, therefore, is a welcome addition to the scholarship devoted to excavating the depth and richness of Kerouac’s work. Unlike previous documentaries, this one focuses exclusively on what has sometimes been called his last great novel, Big Sur (1962). -

Interview with Paul Findley # IS-A-L-2013-002 Interview # 1: January 15, 2013 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Paul Findley # IS-A-L-2013-002 Interview # 1: January 15, 2013 Interviewer: Mark DePue The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 Note to the Reader: Readers of the oral history memoir should bear in mind that this is a transcript of the spoken word, and that the interviewer, interviewee and editor sought to preserve the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein. We leave these for the reader to judge. DePue: Today is Tuesday, January 15, 2013. My name is Mark DePue. I’m the Director of Oral History with the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. Today I’m in Jacksonville, Illinois, specifically, at Illinois College, Whipple Hall. I’m with Congressman Paul Findley. Good morning, sir. Findley: Good morning. DePue: I’ve been looking forward to this interview. I’ve started to read your autobiography. You’ve lived a fascinating life. Today I want to ask you quite a bit to get your story about growing up here in Jacksonville and your military experiences during World War II, and maybe a little bit beyond that, as well. -

Naked Lunch for Lawyers: William S. Burroughs on Capital Punishment

Batey: Naked LunchNAKED for Lawyers: LUNCH William FOR S. Burroughs LAWYERS: on Capital Punishme WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS ON CAPITAL PUNISHMENT, PORNOGRAPHY, THE DRUG TRADE, AND THE PREDATORY NATURE OF HUMAN INTERACTION t ROBERT BATEY* At eighty-two, William S. Burroughs has become a literary icon, "arguably the most influential American prose writer of the last 40 years,"' "the rebel spirit who has witch-doctored our culture and consciousness the most."2 In addition to literature, Burroughs' influence is discernible in contemporary music, art, filmmaking, and virtually any other endeavor that represents "what Newt Gingrich-a Burroughsian construct if ever there was one-likes to call the counterculture."3 Though Burroughs has produced a steady stream of books since the 1950's (including, most recently, a recollection of his dreams published in 1995 under the title My Education), Naked Lunch remains his masterpiece, a classic of twentieth century American fiction.4 Published in 1959' to t I would like to thank the students in my spring 1993 Law and Literature Seminar, to whom I assigned Naked Lunch, especially those who actually read it after I succumbed to fears of complaints and made the assignment optional. Their comments, as well as the ideas of Brian Bolton, a student in the spring 1994 seminar who chose Naked Lunch as the subject for his seminar paper, were particularly helpful in the gestation of this essay; I also benefited from the paper written on Naked Lunch by spring 1995 seminar student Christopher Dale. Gary Minda of Brooklyn Law School commented on an early draft of the essay, as did several Stetson University colleagues: John Cooper, Peter Lake, Terrill Poliman (now at Illinois), and Manuel Ramos (now at Tulane) of the College of Law, Michael Raymond of the English Department and Greg McCann of the School of Business Administration. -

KEROUAC, JACK, 1922-1969. John Sampas Collection of Jack Kerouac Material, Circa 1900-2005

KEROUAC, JACK, 1922-1969. John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, circa 1900-2005 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Kerouac, Jack, 1922-1969. Title: John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, circa 1900-2005 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1343 Extent: 2 linear feet (4 boxes) and 1 oversized papers box (OP) Abstract: Material collected by John Sampas relating to Jack Kerouac and including correspondence, photographs, and manuscripts. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Related Materials in Other Repositories Jack Kerouac papers, New York Public Library Related Materials in This Repository Jack Kerouac collection and Jack and Stella Sampas Kerouac papers Source Purchase, 2015 Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, circa 1900-2005 Manuscript Collection No. 1343 Citation [after identification of item(s)], John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. -

What Are You If Not Beat? – an Individual, Nothing

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy “What are you if not beat? – An individual, nothing. They say to be beat is to be nothing.”1 Individual and Collective Identity in the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Dr. Sarah Posman fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” by Sarah Devos May 2014 1 From “Variations on a Generation” by Gregory Corso 0 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Posman for keeping me motivated and for providing sources, instructive feedback and commentaries. In addition, I would like to thank my readers Lore, Mathieu and my dad for their helpful additions and my library companions and friends for their driving force. Lastly, I thank my two loving brothers and especially my dad for supporting me financially and emotionally these last four years. 1 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1. Ginsberg, Beat Generation and Community. ............................................................ 7 Internal Friction and Self-Promotion ...................................................................................... 7 Beat ......................................................................................................................................... 8 ‘Generation’ & Collective Identity ......................................................................................... 9 Ambivalence in Group Formation -

This Is Not a Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections Walter Gainor Moore Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2015 This Is Not A Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections Walter Gainor Moore Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Recommended Citation Moore, Walter Gainor, "This Is Not A Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections" (2015). Open Access Dissertations. 1421. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/1421 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School Form 30 Updated 1/15/2015 PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Walter Gainor Moore Entitled THIS IS NOT A DISSERTATION. (NEO)NEO-BOHEMIAN CONNECTIONS For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Is approved by the final examining committee: Lance A. Duerfahrd Chair Daniel Morris P. Ryan Schneider Rachel L. Einwohner To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Thesis/Dissertation Agreement, Publication Delay, and Certification Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 32), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy of Integrity in Research” and the use of copyright material. Approved by Major Professor(s): Lance A. Duerfahrd Approved by: Aryvon Fouche 9/19/2015 Head of the Departmental Graduate Program Date THIS IS NOT A DISSERTATION. (NEO)NEO-BOHEMIAN CONNECTIONS A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Walter Moore In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Lance, my advisor for this dissertation, for challenging me to do better; to work better—to be a stronger student. -

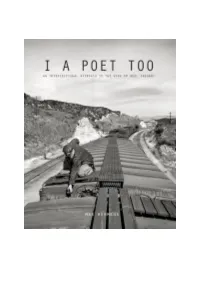

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis. -

World at War and the Fires Between War Again?

World at War and the Fires Between War Again? The Rhodes Colossus.© The Granger Collection / Universal Images Group / ImageQuest 2016 These days there are very few colonies in the traditional sense. But it wasn't that long ago that colonialism was very common around the world. How do you think your life would be different if this were still the case? If World War II hadn’t occurred, this might be a reality. As you've already learned, in the late 19th century, European nations competed with one another to grab the largest and richest regions of the globe to gain wealth and power. The imperialists swept over Asia and Africa, with Italy and France taking control of large parts of North Africa. Imperialism pitted European countries against each other as potential competitors or threats. Germany was a late participant in the imperial game, so it pursued colonies with a single-minded intensity. To further its imperial goals, Germany also began to build up its military in order to defend its colonies and itself against other European nations. German militarization alarmed other European nations, which then began to build up their militaries, too. Defensive alliances among nations were forged. These complex interdependencies were one factor that led to World War I. What Led to WWII?—Text Version Review the map description and the descriptions of the makeup of the world at the start of World War II (WWII). Map Description: There is a map of the world. There are a number of countries shaded four different colors: dark green, light green, blue, and gray. -

2 L'esplosione Implosiva Di Luciano Bianciardi in Natura Società

LAURA BARDELLI L’esplosione implosiva di Luciano Bianciardi In Natura Società Letteratura, Atti del XXII Congresso dell’ADI - Associazione degli Italianisti (Bologna, 13-15 settembre 2018), a cura di A. Campana e F. Giunta, Roma, Adi editore, 2020 Isbn: 9788890790560 Come citare: https://www.italianisti.it/pubblicazioni/atti-di-congresso/natura-societa-letteratura [data consultazione: gg/mm/aaaa] 2 Natura Società Letteratura © Adi editore 2020 LAURA BARDELLI L’esplosione implosiva di Luciano Bianciardi Ribolla, 4 maggio 1954. I corpi dei 43 minatori estratti dalla miniera della Montecatini non hanno più voce per gridare che anche questa volta, come spesso recitano i bollettini dei disastri nostrani, “la tragedia si poteva evitare”. Luciano Bianciardi tributa loro l’onore e l’onere della verità nel libro-documento scritto con Cassola, se li porta dietro fin nell’astiosa e tacchettante Milano, progetta l’esplosione per contrappasso del «torracchione di vetro e di cemento», traduce come un forzato, s’innamora, sogna il suo Garibaldi. Il rapporto uomo-ambiente ai tempi del boom economico visto attraverso il prisma dello scrittore grossetano. Nello stretto giro di tre cocktail esplosivi si brucia la breve miccia con cui Luciano Bianciardi accende una carriera letteraria corrosiva e consuma la sua esistenza. Il primo, quello a base di grisù e fatale inadempienza, confezionato da Madre Terra con il colpevole concorso della Montecatini, proprietaria di gran parte delle miniere maremmane, deflagra letteralmente nelle gallerie di Ribolla il 4 maggio del 1954, portandosi via la vita di quarantatré minatori. Le loro larve continueranno ad infestare i giorni grigi e le notti bianche dello scrittore, che nella Vita agra ne ricorda i funerali: Rimasi quattro giorni nella piana sotto Montemassi, dallo scoppio fino ai funerali, e li vidi tirare su quarantatré morti, tanti fagotti dentro una coperta militare. -

The Portable Beat Reader Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE PORTABLE BEAT READER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ann Charters | 688 pages | 07 Oct 2014 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780142437537 | English | London, United Kingdom The Portable Beat Reader PDF Book What We Like Waterproof design is lightweight Glare-free screen. Nov 21, Dayla rated it it was amazing. See all 6 brand new listings. Night mode automatically tints the screen amber for midnight reading. The author did an excellent job of reviewing each writer - their history, works, etc - before each section. Diane DiPrima Dinners and Nightmares excerpt 5. Animal Farm and by George Orwell and A. Get BOOK. Quick Links Amazon. Although in retrospect, my knowledge was hardly rich with understanding, even though I'd read some Burroughs, knew of Kerouac and On the Road , Ginsberg and Howl. And last but not least, Family Library links your Amazon account to that of your relatives to let you conveniently share books. Again, no need to sit down and read the whole thing. She guides you through all the sections of the Beats Generation: Kerouac's group in New York, the San Francisco Poets, and the other groups that were inspired by the work these groups produced. Members Reviews Popularity Average rating Mentions 1, 7 10, 4. First off, Amazon has included a brand-new front light that allows you to read in the dark, something that was previously only available on the more expensive Kindle Paperwhite. But Part 5 was my joy! E-readers are also a great option for kids to explore. Status Charters, Ann Editor primary author all editions confirmed Baraka, Amiri Contributor secondary author all editions confirmed Bremser, Ray Contributor secondary author all editions confirmed Bukowski, Charles Contributor secondary author all editions confirmed Burroughs, William S. -

“But Cantos Oughta Sing”: Jack Kerouac's Mexico City

The Albatross is pleased to feature the graduating essay of Jack Derricourt which won the 2011 English Honours Essay Scholarship. “But Cantos Oughta Sing”: Jack Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues and the British-American Poetic Tradition Jack Derricourt During the post-war era of the 1950s, American poets searched for a new direction. The Cold War was rapidly reshaping the culture of the United States, including its literature, stimulating a variety of poets to rein- terpret the historical lineage of poetic expression in the English language. Allen Grossman, a poet and critic who undertook such a reshaping in the fifties, turns to the figure of Caedmon from the Venerable Bede’s early eighth century Ecclesiastical History of the English People to seek out the roots of British-American poets. For Grossman, Caedmon represents an important starting point within the long tradition of English-language poetry: Bede’s visionary layman crafts a non-human narrative—a form of truth witnessed beyond the confines of social institutions, or transcend- ent truth—and makes it intelligible through the formation of conventional symbols (Grossman 7). The product of this poetic endeavour is the song. The figure of Caedmon also appears in the writings of Robert Duncan as a model of poetic transference: I cannot make it happen or want it to happen; it wells up in me as if I were a point of break-thru for an “I” that may be any person in the cast of a play, that may like the angel speaking to Caedmon to command “Sing me some thing.” When that “I” is lost, when the voice of the poem is lost, the matter of the poem, the intense infor- mation of the content, no longer comes to me, then I know I have to wait until that voice returns. -

The Importance of Neal Cassady in the Work of Jack Kerouac

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2016 The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac Sydney Anders Ingram As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ingram, Sydney Anders, "The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac" (2016). MSU Graduate Theses. 2368. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/2368 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, English By Sydney Ingram May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Sydney Anders Ingram ii THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC English Missouri State University, May 2016 Master of Arts Sydney Ingram ABSTRACT Neal Cassady has not been given enough credit for his role in the Beat Generation.