Risk Assessment and Monitoring of Ancient Egyptian Quarry Landscapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War and Insurgency in the Western Sahara

Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. STRATEGIC STUDIES INSTITUTE The Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) is part of the U.S. Army War College and is the strategic-level study agent for issues relat- ed to national security and military strategy with emphasis on geostrategic analysis. The mission of SSI is to use independent analysis to conduct strategic studies that develop policy recommendations on: • Strategy, planning, and policy for joint and combined employment of military forces; • Regional strategic appraisals; • The nature of land warfare; • Matters affecting the Army’s future; • The concepts, philosophy, and theory of strategy; and, • Other issues of importance to the leadership of the Army. Studies produced by civilian and military analysts concern topics having strategic implications for the Army, the Department of Defense, and the larger national security community. In addition to its studies, SSI publishes special reports on topics of special or immediate interest. These include edited proceedings of conferences and topically-oriented roundtables, expanded trip reports, and quick-reaction responses to senior Army leaders. The Institute provides a valuable analytical capability within the Army to address strategic and other issues in support of Army participation in national security policy formulation. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press WAR AND INSURGENCY IN THE WESTERN SAHARA Geoffrey Jensen May 2013 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. -

Early Hydraulic Civilization in Egypt Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu Early Hydraulic Civilization in Egypt oi.uchicago.edu PREHISTORIC ARCHEOLOGY AND ECOLOGY A Series Edited by Karl W. Butzer and Leslie G. Freeman oi.uchicago.edu Karl W.Butzer Early Hydraulic Civilization in Egypt A Study in Cultural Ecology Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London oi.uchicago.edu Karl Butzer is professor of anthropology and geography at the University of Chicago. He is a member of Chicago's Committee on African Studies and Committee on Evolutionary Biology. He also is editor of the Prehistoric Archeology and Ecology series and the author of numerous publications, including Environment and Archeology, Quaternary Stratigraphy and Climate in the Near East, Desert and River in Nubia, and Geomorphology from the Earth. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London ® 1976 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1976 Printed in the United States of America 80 79 78 77 76 987654321 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Butzer, Karl W. Early hydraulic civilization in Egypt. (Prehistoric archeology and ecology) Bibliography: p. 1. Egypt--Civilization--To 332 B. C. 2. Human ecology--Egypt. 3. Irrigation=-Egypt--History. I. Title. II. Series. DT61.B97 333.9'13'0932 75-36398 ISBN 0-226-08634-8 ISBN 0-226-08635-6 pbk. iv oi.uchicago.edu For INA oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu CONTENTS List of Illustrations Viii List of Tables ix Foreword xi Preface xiii 1. -

48-59, 2012 Issn: 2077-4508

48 International Journal of Environment 1(1): 48-59, 2012 ISSN: 2077-4508 Present Status and Long Term Changes of Phytoplankton in Closed Saline Basin with Special Reference to the Effect of Salinity Mohamad Saad Abd El-Karim National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, 101 El-Kasr El-Eny St., Cairo, Egypt ABSTRACT The present status of phytoplankton communities was studied at 10 stations during late summer and mid winter 2011. A total of 8 classes, 84 genera and 197 species were recorded in the lake. The recorded classes were diatoms, chlorophytes, cyanobacteria, dinoflagellates, cryptophytes, euglenophytes, and two groups recorded for the first time which are prasinophytes and coccolithophorbide. Diatoms had 27 genera with 89 species, chlorophytes had 25 genera with 45 species, cyanobacteria had 11 genera with 24 species, dinoflagellates had 13 genera with 26 species, cryptophytese had 4 genera with 5 species, euglenophytes had 1 genus with 2 species. Prasinophyceae and coccolithophorbide which represented by 1 genus with 4 species and 2 genera with 2 species, respectively. The application of TWINSPAN, and DCA techniques classified the samples into 4 groups using 197 species. The classification patterns occurred according to the salinity gradient from least salinity at the easternmost stations close to the fresh water inlets to the highest salinity at the westernmost area. CCA biplot showed that transparency, temperature, pH, TP, and salinity had great influence on phytoplankton species compared with the effect of BOD and TIN. CCA biplot indicated that species of stations 9 and 10 were highly positively affected by salinity. The other groups were partially or negatively affected by salinity. -

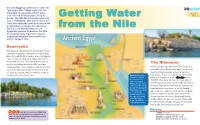

Getting Water from the Nile

Ancient Egypt has often been called the “gift of the Nile.” What a gift it is! The important river provided food, water, GRADE 7 and rich soil for the people along its Getting Water RH.6-8.10 banks. The Nile River became essential to the civilizations that have thrived for centuries along the river and have relied on farming as a means for obtaining food. It is no wonder that ancient from the Nile Egyptians learned to harness the Nile, developing many ingenious ways to irrigate the land that surrounded the world’s longest river. Ancient Egypt Reservoirs What do you do when floodwaters get too high? That was a problem that Egyptians sometimes had to worry about during the yearly Nile River flooding. Some crafty Egyptian engineers came up with a way to manage this problem about 4,000 years ago. They realized that by widening and then deepening a lake near the Nile, sometimes The Nilometer called Lake Moeris, excess floodwater might be able to be Ancient Egyptians knew that the Nile River flooded in a stored in the lake. It was an ancient version of modern predictable pattern. However, how much it flooded could reservoirs used to store water. The water then could be mean the difference between a great harvest and a used to irrigate crops at a later time. Egyptian pharaohs huge disaster. To help determine the type of flood that learned to use the might occur, Egyptians developed nilometers around nilometers for a 3500 BCE. Made out of limestone, the stone markers different purpose. -

The Limbs Factory: Circuits of Fear and Hope and the Political Imagination on the Western Sahara

The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy The Limbs Factory: Circuits of Fear and Hope and the Political Imagination on the Western Sahara A Thesis Submitted to Cynthia Nelson Institute for Gender and Women’s Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender and Women’s Studies in Middle East/ North Africa Kenza Yousfi Committee members: Dr. Martina Rieker, IGWS, AUC Dr. Hanan Sabea, SAPE, AUC Dr. Nizar Messari, SHSS, AUI May/2015 . Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without the people who have supported me all the way through the stress, confusion, and passion that enabled me to write. I thank my committee members: Martina, Hanan, and Nizar, for their intellectual engagement and the political horizons they have opened to me throughout the past few years. My friends around the globe, I hope that reading these pages compensate you with the hours of counseling and listening you had to lead me through. Only you could understand my craziness. My family, although very far from sharing any political ideas, I must be thankful for your encouragement and concern of safety even when you did not know where in the world I was. I thank all the Saharawis who wanted to help by all means while I was in the camps. Many thanks for the NUSW for coordinating my stay and providing me with the logistics, and to the family that hosted me like a family member, not a stranger. I owe a particular debt to one person who shall remain unnamed for his own safety, who made my access to the Saharawi camps possible, and who showed a concern about my research and safety. -

Ancient Stone Quarry Landscapes In

QuarryScapes: quarry stone ancient Mediterranean landscapes in the Eastern QuarryScapes: ancient QuarryScapes:stone quarry landscapes ancient stone in quarrythe Eastern landscapes Mediterranean in the EasternGeological Survey of MediterraneanNorway, Special Publication, 12 Geological Survey of Norway, Special Publication, 12 Geological Survey of Norway, Special Publication, 12 Abu-Jaber et al. (eds.) et al. 12 Abu-Jaber Special Publication, Geological Survey of Norway, Abu-Jaber, N., Bloxam, E.G., Degryse,P. and Heldal, T. (eds.) Geological Survey of Norway, Special Publication, 12 The NGU Special Publication series comprises consecutively numbered volumes containing papers and proceedings from national and international symposia or meetings dealing with Norwegian and international geology, geophysics and geochemistry; excursion guides from such symposia; and in some cases papers of particular value to the international geosciences community, or collections of thematic articles. The language of the Special Publication series is English. Editor: Trond Slagstad ©2009 Norges geologiske undersøkelse Published by Norges geologiske undersøkelse (Geological Survey of Norway) NO-7491 Norway All Rights reserved ISSN: 0801-5961 ISBN: 978-82-7385-138-3 Design and print: Trykkpartner Grytting AS Cover illustration: Situated far out in the Eastern Desert in Egypt, Mons Claudianus is one of the most spectacular quarry landscapes in Egypt. The white tonalite gneiss was called marmor claudianum by the Romans, and in particular it was used for large objects such as columns and bathtubs. Giant columns of the stone can be seen in front of Pantheon in Rome. Photo by Tom Heldal. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF NORWAY SPECIAL PUBLICATION n Contents Introduction Abu-Jaber, N., Bloxam, E.G., Degryse, P. -

History and Culture.Indd

History & Culture Table of Contents Map of Jordan 1 L.Tiberius Umm Qays Welcome 2 Irbid Jaber Amman 4 Pella Hemmeh Ramtha er As-Salt HISTORY & CULTURE12 ITINERARIES Ajlun Mafraq Madaba 14 dan Riv Jerash Deir 'Alla Umm al-Jimal 1 Day Tour Options: Jor Umm Ar-Rasas1. Jerash, Ajlun 16 ey Salt Qasr Al Hallabat Mount Nebo2. Amman (City Tour) 17 all Zarqa Marka 3. Madaba, Mount Nebo, Bethany Beyond the Jordan V dan Jordan Valley & The Dead Sea 18 Jor Amman Iraq al-Amir Qusayr Amra Azraq Karak 20 Bethany Beyond The Jordan Mt. Nebo Qasr Al Mushatta 3 Day Itinerary: Dead Sea Spas Queen Alia Qasr Al Kharrana Petra 22 Madaba International Day 1. Amman, Jerash, Madaba and Dead Sea - Overnight in Ammana Airport e Hammamat Ma’in Aqaba Day 2. Petra - Overnight in26 Little Petra S d Dhiban a Umm Ar-Rasas Jerash Day 3. Karak, Madaba and30 Mount Nebo - Overnight in Ammane D Ajlun 36 5 Day Itinerary: Umm Al-Jimal 38 Qatraneh Day 1. Amman, Jerash, Ajlun - Overnight in Amman Karak Pella 39 Mu'ta Day 2. Madaba, Mount Nebo, Karak - Overnight at PetraAl Mazar aj-Janubi Umm QaysDay 3. Petra - Overnight at40 Petra Shawbak Day 4. Wadi Rum - Overnight42 Dead Sea Tafileh Day 5. Bethany Beyond The Jordan MAP LEGEND Desert Umayyad Castles 44 History & Culture Itineraries 49 Historical Site Shawbak Highway Castle Desert Wadi Musa Petra Religious Site Ma'an Airport Ras an-Naqab Road For further information please contact: Highway Jordan Tourism Board: Tel: +962 6 5678444. It is open daily (08:00- Railway 16:00) except Fridays. -

The Fayoum, the Seila Pyramid, Fag El-Gamous and Its Nearby Cities

Chapter 1 The Fayoum, The Seila Pyramid, Fag el-Gamous and its Nearby Cities Kerry Muhlestein, Cannon Fairbairn and Ronald A. Harris Because the excavations discussed in this volume take place in the Fayoum and cover a time period that spans from the Old Kingdom through the Byzan- tine era, many readers will find it helpful to understand the history, geography, and geology of the Fayoum. Here we provide a brief outline of those subjects. This is not intended to present new information or to be a definitive discus- sion. Rather, it is aimed at contextualizing the rest of the material presented in this volume, and thus making all of its information more accessible. The Fag el-Gamous cemetery and the Seila Pyramid are located on the eastern edge of the Fayoum, just north of the center of the Fayoum’s north/south axis. Anciently called the “Garden of Egypt,”1 the Fayoum sits in a large natural depression west of the Nile Valley.2 The depression is about 65 kilometers across and covers about 12,000 square kilometers.3 While some refer to it as the largest oasis in the Western Desert,4 others protest that this is in fact a false classification because the Fayoum receives the majority of its water from the Nile and not an independent spring as with traditional oases.5 No matter how one wishes to classify this region of Egypt, it is an area of unique geography, vegetation, and wildlife, with a rich history and an abundance of archaeology. 1 A.E. Boak, “Irrigation and Population in the Faiyum, the Garden of Egypt,” Geographical Re- view 16/3 (July 1926): 355; Alberto Siliotti, The Fayoum and Wadi El-Rayan (Cairo: The Ameri- can University in Cairo Press, 2003), 15; R. -

The Mellah: Exploring Moroccan Jewish and Muslim Narratives on Urban Space

The Mellah: Exploring Moroccan Jewish and Muslim Narratives on Urban Space By: Tamar Schneck Advisor: Professor Jonathan Decter Seniors Honors Thesis Islamic & Middle Eastern Studies Program Brandeis University 2012-2013 Acknowledgements Researching and writing this thesis has been a learning experience that I know will shape my future experiences in school and beyond. I would like to express my sincere thanks to my advisor, Professor Decter for guiding me through this project and advising me along the way. I would also like to thank Professor Carl Sharif El- Tobgui for assisting with understanding the difficult Arabic texts. Additionally, I owe gratitude to my friends who are native Hebrew and Arabic speakers; their assistance was vital. Lastly, I would like to thank everyone who is reading this. I hope you enjoy! 2 Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 A Brief History of Moroccan Jewish Settlement......................................................................7 Source Review ...................................................................................................................................................11 Chapter 1: Jewish Perspectives.........................................................................................25 1.1 OriGinal Myth.............................................................................................................................25 1.2 Stories Retold.............................................................................................................................................33 -

Desert Fayum Fayum Desert Reinvestigated Desert Fayum He Neolithic in Egypt Is Thought to Have Arrived Via Diffusion from an Origin in Southwest Asia

READ ONLY / NO DOWNLOAD The The The Desert Fayum Desert Fayum Reinvestigated Desert Fayum he Neolithic in Egypt is thought to have arrived via diffusion from an origin in southwest Asia. Reinvestigated TIn this volume, the authors advocate an alter- native approach to understanding the development of food production in Egypt based on the results of The Early to Mid-Holocene Landscape new fieldwork in the Fayum. They present a detailed study of the Fayum archaeological landscape using Archaeology of the Fayum North Shore, Egypt an expanded version of low-level food production to organize observations concerning paleoenviron- ment, socioeconomy, settlement, and mobility. While Reinvestigated domestic plants and animals were indeed introduced to the Fayum from elsewhere, when a number of aspects of the archaeological record are compared, a settlement system is suggested that has no obvious analogues with the Neolithic in southwest Asia. The results obtained from the Fayum are used to assess other contemporary sites in Egypt. A landmark publication for Egyptian prehistory and for the general understand- Edited by ing of cultural and environmental change in North Africa and the Mediterranean. David Wengrow, Professor of Comparative Archaeology Simon J. Holdaway UCL Institute of Archaeology and Willeke Wendrich This book results from a remarkable international collaboration that brings together archaeological and geoarchaeological data to provide a new land- scape understanding of the early to mid-Holocene in the Desert Fayum. The results are of great significance, demonstrating a distinct regional character Holdaway to the adoption of farming and substantiating the wider evidence for a polycen- tric development of the Neolithic in the Middle East. -

EARLY CIVILIZATIONS of the OLD WORLD to the Genius of Titus Lucretius Carus (99/95 BC-55 BC) and His Insight Into the Real Nature of Things

EARLY CIVILIZATIONS OF THE OLD WORLD To the genius of Titus Lucretius Carus (99/95 BC-55 BC) and his insight into the real nature of things. EARLY CIVILIZATIONS OF THE OLD WORLD The formative histories of Egypt, the Levant, Mesopotamia, India and China Charles Keith Maisels London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 First published in paperback 2001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 1999 Charles Keith Maisels All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 0-203-44950-9 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-45672-6 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-10975-2 (hbk) ISBN 0-415-10976-0 (pbk) CONTENTS List of figures viii List of tables xi Preface and acknowledgements -

The Evolution of Irrigation in Egypt's Fayoum Oasis State, Village and Conveyance Loss

THE EVOLUTION OF IRRIGATION IN EGYPT'S FAYOUM OASIS STATE, VILLAGE AND CONVEYANCE LOSS By DAVID HAROLD PRICE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1993 Copyright 1993 by David Harold Price . ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the following people for their various contributions to the completion of this manuscript and the fieldwork on which it is based: Russ Bernard, Linda Brownell, Ronald Cohen, Lawry Gold, Magdi Haddad, Madeline Harris, Fekri Hassan, Robert Lawless, Bill Keegan, Madelyn Lockheart, Mo Madanni, Ed Malagodi, Mark Papworth, Midge Miller Price, Lisa Queen and Mustafa Suliman. A special note of thanks to my advisor Marvin Harris for his support and encouragement above and beyond the call of duty. Funding for field research in Egypt was provided by a National Science Foundation Dissertation Research Grant (BNS-8819558) PREFACE Water is important to people who do not have it, and the same is true of power. —Joan Didion This dissertation is a study of the interaction among particular methods of irrigation and the political economy and ecology of Egypt's Fayoum region from the Neolithic period to the present. It is intended to be a contribution to the long-standing debate about the importance of irrigation as a cause and/or effect of specific forms of local, regional and national sociopolitical institutions. I lived in the Fayoum between July 1989 and July 1990. I studied comparative irrigation activities in five villages located in subtly different ecological habitats.