View on the Review Stand What I Saw on the Parade Ground Was Pure, Unadulterated Rabble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser

ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser: Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff, May 2019 June 2019: Admiral Sir Antony D. Radakin: First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff, June 2019 (11/1965; 55) VICE-ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 February 2016: Vice-Admiral Sir Benjamin J. Key: Chief of Joint Operations, April 2019 (11/1965; 55) July 2018: Vice-Admiral Paul M. Bennett: to retire (8/1964; 57) March 2019: Vice-Admiral Jeremy P. Kyd: Fleet Commander, March 2019 (1967; 53) April 2019: Vice-Admiral Nicholas W. Hine: Second Sea Lord and Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, April 2019 (2/1966; 55) Vice-Admiral Christopher R.S. Gardner: Chief of Materiel (Ships), April 2019 (1962; 58) May 2019: Vice-Admiral Keith E. Blount: Commander, Maritime Command, N.A.T.O., May 2019 (6/1966; 55) September 2020: Vice-Admiral Richard C. Thompson: Director-General, Air, Defence Equipment and Support, September 2020 July 2021: Vice-Admiral Guy A. Robinson: Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied Command, Transformation, July 2021 REAR ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 July 2016: (Eng.)Rear-Admiral Timothy C. Hodgson: Director, Nuclear Technology, July 2021 (55) October 2017: Rear-Admiral Paul V. Halton: Director, Submarine Readiness, Submarine Delivery Agency, January 2020 (53) April 2018: Rear-Admiral James D. Morley: Deputy Commander, Naval Striking and Support Forces, NATO, April 2021 (1969; 51) July 2018: (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Keith A. Beckett: Director, Submarines Support and Chief, Strategic Systems Executive, Submarine Delivery Agency, 2018 (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Malcolm J. Toy: Director of Operations and Assurance and Chief Operating Officer, Defence Safety Authority, and Director (Technical), Military Aviation Authority, July 2018 (12/1964; 56) November 2018: (Logs.) Rear-Admiral Andrew M. -

„Kolíska“ Šťastia Sagan Skončil!

Piatok 9. 7. 2021 75. ročník • číslo 156 cena 0,90 pre predplatiteľov 0,70 App Store pre iPad a iPhone / Google Play pre Android Sagan skončil! Černák píše Hokejista Tampy Bay je prvý Slovák, históriu ktorý obhájil Stanleyho pohár Strana 22 Strany 20 a 21 Peter Sagan odstúpil z Tour de France. Cyklista tímu Bora-hansgrohe skončil pre zhoršujúce sa zranenie kolena, ktoré utrpel po páde v závere 3. etapy. Neustále musel byť pod dohľadom lekára. FOTO BORA-HANSGROHE Strany 3 – 7 „Kolíska“ šťastia Anglicko zdolalo v semifinále ME Dánsko 2:1 po predĺžení. Hráči z kolísky futbalu si prvý raz zahrajú o cennú trofej na kontinentálnom šampionáte. V nedeľu nastúpia proti Taliansku. FOTO TASR/AP FOTO INSTAGRM (eč) Prvý zápas 1. predkola Konferenčnej ligy: MŠK Žilina – FC Dila Gori 5:1 (2:0) 2 NÁZORY piatok 9. 7. 2021 PRIAMA REČ MARTINA PETRÁŠA Zaslúžené finálové obsadenie Finále európskeho šampionátu obsta- futbalistom, ktorí sa stotožnili s jeho filo- „ O trofej zabojujú dva tímy, ktoré že palce držím Taliansku, kde som nielen rajú Taliansko a Anglicko. Absolútne za- zofiou. Mužstvo predvádza fantastický hrával, ale stále tam trávim veľkú časť slúžene. O trofej zabojujú dva tímy, ktoré futbal v duchu moderných trendov. Hráči na turnaji predvádzajú najlepší futbal. svojho života. V krajine vládla podobná na turnaji predvádzajú najlepší futbal. Ve- majú okrem fyzického fondu aj kvalitu eufória naposledy v roku 2006, keď sa dú ich tréneri, ktorí dokázali zmeniť dl- a pritom Taliansko nič nestratilo zo svojej na tých istých postoch ako v národnom tí- reth Southgate rovnako ako jeho náproti- stali majstrami sveta. -

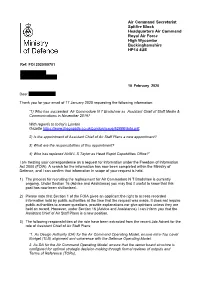

Information Regarding Who Has Succeeded Air Commodore N T

Air Command Secretariat i Spitfire Block Headquarters Air Command Royal Air Force High Wycombe Buckinghamshire HP14 4UE Ref: FOI 2020/00701 10 February 2020 Dear Thank you for your email of 17 January 2020 requesting the following information: “1) Who has succeeded Air Commodore N T Bradshaw as Assistant Chief of Staff Media & Communications in November 2019? With regards to today's London Gazette https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/62888/data.pdf, 2) Is the appointment of Assistant Chief of Air Staff Plans a new appointment? 3) What are the responsibilities of this appointment? 4) Who has replaced AVM L S Taylor as Head Rapid Capabilities Office?” I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA). A search for the information has now been completed within the Ministry of Defence, and I can confirm that information in scope of your request is held. 1) The process for recruiting the replacement for Air Commodore N T Bradshaw is currently ongoing. Under Section 16 (Advice and Assistance) you may find it useful to know that this post has now been civilianised. 2) Please note that Section 1 of the FOIA gives an applicant the right to access recorded information held by public authorities at the time that the request was made. It does not require public authorities to answer questions, provide explanations nor give opinions unless they are held on record. However, under Section 16 (Advice and Assistance) I can inform you that the Assistant Chief of Air Staff Plans is a new position. -

The Morgue File 2010

the morgue file 2010 DONE BY: ASSIL DIAB 1850 1900 1850 to 1900 was known as the Victorian Era. Early 1850 bodices had a Basque opening over a che- misette, the bodice continued to be very close fitting, the waist sharp and the shoulder less slanted, during the 1850s to 1866. During the 1850s the dresses were cut without a waist seam and during the 1860s the round waist was raised to some extent. The decade of the 1870s is one of the most intricate era of women’s fashion. The style of the early 1870s relied on the renewal of the polonaise, strained on the back, gath- ered and puffed up into an detailed arrangement at the rear, above a sustaining bustle, to somewhat broaden at the wrist. The underskirt, trimmed with pleated fragments, inserting ribbon bands. An abundance of puffs, borders, rib- bons, drapes, and an outlandish mixture of fabric and colors besieged the past proposal for minimalism and looseness. women’s daywear Victorian women received their first corset at the age of 3. A typical Victorian Silhouette consisted of a two piece dress with bodice & skirt, a high neckline, armholes cut under high arm, full sleeves, small waist (17 inch waist), full skirt with petticoats and crinoline, and a floor length skirt. 1894/1896 Walking Suit the essential “tailor suit” for the active and energetic Victorian woman, The jacket and bodice are one piece, but provide the look of two separate pieces. 1859 zouave jacket Zouave jacket is a collarless, waist length braid trimmed bolero style jacket with three quarter length sleeves. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Charles B. Slonim, M.D. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Ophthalmology James A. Haley Veterans Administration Eye Clinic 10770 N. 46th Street. Tampa, Florida 33617 Telephone: (813) 972-2000 ext. 7513 E-mail: [email protected] June 26, 2021 Education College: Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, B.A., 1974 Medical School: New York Medical College, Valhalla, New York, M.D., 1978 Internship: Mt. Sinai Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio, Flexible Medical/Surgical, 1978-1979 Residency: Mt. Sinai Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio, Ophthalmology, 1979-1981 Chief Resident: Mt. Sinai Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio, Ophthalmology, 1981-1982 Academic Positions Professor, Department of Ophthalmology University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, Florida Affiliate Professor, Department of Plastic Surgery University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, Florida Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Ophthalmology University of Florida School of Medicine, Gainesville, Florida Work Experience iuvo BioScience, Rush, NY Chief Medical Officer, Ophthalmology Team – July 2018 - present Oculos Development Services, Tampa, FL Chief Medical Officer – August 2018 - present Point Guard Partners, LLC, Tampa, Florida Vice-President of Medical Affairs – August 2012 – present Medical Monitor – August 2012 - present James A. Haley VA Hospital, Tampa, Florida Ophthalmology Department – Chief – July 2018 - present Full time Oculoplastic surgeon - October 2009 – present Part time Oculoplastic surgeon -

Air Chief Marshal Frank Robert MILLER, CC, CBE, CD Air Member

Air Chief Marshal Frank Robert MILLER, CC, CBE, CD Air Member Operations and Training (C139) Chief of the RCAF Post War Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff and First Chief of Staff 01 August 1964 - 14 July 1966 Born: 30 April 1908 Kamloops, British Columbia Married: 03 May 1938 Dorothy Virginia Minor in Galveston, Texas Died: 20 October 1997 Charlottesville, Virginia, USA (Age 89) Honours CF 23/12/1972 CC Companion of the Order of Canada Air Chief Marshal RCAF CG 13/06/1946 CBE Commander of the Order of the British Empire Air Vice-Marshal RCAF LG 14/06/1945+ OBE Officer of the Order of the British Empire Air Commodore RCAF LG 01/01/1945+ MID Mentioned in Despatches Air Commodore RCAF Education 1931 BSc University of Alberta (BSc in Civil Engineering) Military 01/10/1927 Officer Cadet Canadian Officer Training Corps (COTC) 15/09/1931 Pilot Officer Royal Canadian Air Force 15/10/1931 Pilot Officer Pilot Training at Camp Borden 16/12/1931 Flying Officer Receives his Wings 1932 Flying Officer Leaves RCAF due to budget cuts 07/1932 Flying Officer Returns to the RCAF 01/02/1933 Flying Officer Army Cooperation Course at Camp Borden in Avro 621 Tutor 31/05/1933 Flying Officer Completes Army Cooperation Course at Camp Borden 30/06/1933 Flying Officer Completes Instrument Flying Training on Gipsy Moth & Tiger Moth 01/07/1933 Flying Officer Seaplane Conversion Course at RCAF Rockcliffe Vickers Vedette 01/08/1933 Flying Officer Squadron Armament Officer’s Course at Camp Borden 22/12/1933 Flying Officer Completes above course – Flying the Fairchild 71 Courier & Siskin 01/01/1934 Flying Officer No. -

2017 United Soccer League Media Guide

Table of Contents LEAGUE ALIGNMENT/IMPORTANT DATES ..............................................................................................4 USL EXECUTIVE BIOS & STAFF ..................................................................................................................6 Bethlehem Steel FC .....................................................................................................................................................................8 Charleston Battery ......................................................................................................................................................................10 Charlotte Independence ............................................................................................................................................................12 Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC .......................................................................................................................................14 FC Cincinnati .................................................................................................................................................................................16 Harrisburg City Islanders ........................................................................................................................................................18 LA Galaxy II ..................................................................................................................................................................................20 -

IN the COURT of CRIMINAL APPEALS of TENNESSEE at KNOXVILLE November 17, 2015 Session

IN THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS OF TENNESSEE AT KNOXVILLE November 17, 2015 Session STATE OF TENNESSEE v. ETHAN ALEXANDER SELF Appeal from the Criminal Court for Hawkins County No. 13CR154 Jon Kerry Blackwood, Senior Judge No. E2014-02466-CCA-R3-CD – Filed August 29, 2016 The Defendant, Ethan Alexander Self, was found guilty by a Hawkins County Criminal Court jury of first degree premeditated murder. See T.C.A. § 39-13-202 (2014). He was sentenced to life in prison. On appeal, the Defendant contends that (1) the trial court erred in denying his motion to suppress, (2) the State improperly exercised a peremptory challenge to a prospective juror for a race-based reason, (3) the evidence is insufficient to support the conviction, (4) the court erred in denying the Defendant‟s motions for a mistrial based upon the State‟s failure to disclose evidence, (5) the court erred in denying his motions for a mistrial based upon the State‟s eliciting evidence in violation of the court‟s pretrial evidentiary rulings, (6) the court erred in denying his motion for a mistrial based upon the State‟s failure to preserve alarm clocks from the victim‟s bedroom, (7) the court erred in admitting evidence of the Defendant and the victim‟s good relationship and lack of abuse, (8) the court erred in the procedure by which the jury inspected the gun used in the victim‟s homicide, (9) prosecutorial misconduct occurred during the State‟s rebuttal argument, (10) the court erred in failing to instruct the jury on self-defense, (11) cumulative trial error necessitates a new trial, and (12) the trial court improperly sentenced the Defendant. -

November-December 2019

AFFILIATED WITH THE NATIONAL RIFLE ASSOCIATION D.S.S.A. NEWS DELAWARE STATE SPORTSMEN’S ASSOCIATION A PUBLICATION OF THE DELAWARE STATE SPORTSMEN’S ASSOCIATION Visit us on the web: DSSA.us P.O. Box 94, Lincoln, DE 19960 Jeff is also a frequent contributor to the editorial pages DSSA PRESIDENT RUNNING FOR NRA BOARD of local papers, taking on the anti-gun crowd, calling them to By John C. Sigler task for their far-too frequent lies, ensuring that the truth NRA Past President about gun owners and hunters is well represented in the public discourse. He is also a frequent radio commentator It is with great deal of pride and pleasure that I announce who has repeatedly and successfully called the gun-grabbers that my good friend and colleague, DSSA’s current president to task and ensured that the truth is being told to the Jeffrey W. Hague, is now officially a candidate for election to otherwise uneducated public. the Board of Directors of the National Rifle Association of Jeff is an accomplished competitive shooter, having America, Inc. The NRA’s Nominating Committee has just engaged in High Power Rifle competition for over 40 years. released its official list of nominees for the 2020 NRA Board Jeff holds High Master classifications in Conventional High Elections and our own DSSA President Jeff Hague was among Power (“across the course”), Mid-Range, Long Range and NRA those stalwart NRA Members chosen by the committee to International Fullbore Rifle. He is also a member of the help guide NRA through the rocks and shoals of the coming United States Rifle Team (Palma Veteran). -

Namaste: a Party Not to Sell Your Shares??

09/13/2018 Namaste: A Party Not to Sell Your Shares?? OHHHH…the NASDAQ is going to have a field day with this rejection. Namaste Will Never Get a Nasdaq Listing; target $.25 cents ( Updated 9:25am) **** Update**** New information has come to Citron’s attention and its important. New target price $0.25. The French Presse has spoken and a credit to them. Quoting the head of Quebec Cannabis, Linda Bouchard has spoken. The takeaway is “A situation ‘totally unacceptable’”. It goes on to say, Quebec is to investigate Namaste and the article quotes “in violation of several sections of the Quebec and Canadian laws that formally prohibit the promotion of recreational cannabis products.” The College of Nurses of Quebec even imply that NamasteMD might be illegal (source). Tilray has now dropped Namaste too – let the hangover begin (source). Just when you thought you’d seen it all. Two nights ago, in Montreal, Namaste culminated its three‐month long pledge challenge with a party featuring Snoop Dogg. This is a $1 billion company that does not grow cannabis, rather they sell vape pens and have a website that did a paltry $46k in revenue last quarter as they lost $9 million. This is the type of euphoria, hype and promotion that the SEC has been warning investors about. The last few weeks have been strong for Cannabis stocks that trade in the US and investors have gone feverishly wild in creating bubble like valuations. While you can’t blame real companies like Aphria and Canntrust on hoping to join the party through a NASDAQ listing, you have to expect some party crashers to show up. -

Good Chemistry James J

Columbia College Fall 2012 TODAY Good Chemistry James J. Valentini Transitions from Longtime Professor to Dean of the College your Contents columbia connection. COVER STORY FEATURES The perfect midtown location: 40 The Home • Network with Columbia alumni Front • Attend exciting events and programs Ai-jen Poo ’96 gives domes- • Dine with a client tic workers a voice. • Conduct business meetings BY NATHALIE ALONSO ’08 • Take advantage of overnight rooms and so much more. 28 Stand and Deliver Joel Klein ’67’s extraordi- nary career as an attorney, educator and reformer. BY CHRIS BURRELL 18 Good Chemistry James J. Valentini transitions from longtime professor of chemistry to Dean of the College. Meet him in this Q&A with CCT Editor Alex Sachare ’71. 34 The Open Mind of Richard Heffner ’46 APPLY FOR The venerable PBS host MEMBERSHIP TODAY! provides a forum for guests 15 WEST 43 STREET to examine, question and NEW YORK, NY 10036 disagree. TEL: 212.719.0380 BY THOMAS VIncIGUERRA ’85, in residence at The Princeton Club ’86J, ’90 GSAS of New York www.columbiaclub.org COVER: LESLIE JEAN-BART ’76, ’77J; BACK COVER: COLIN SULLIVAN ’11 WITHIN THE FAMILY DEPARTMENTS ALUMNI NEWS Déjà Vu All Over Again or 49 Message from the CCAA President The Start of Something New? Kyra Tirana Barry ’87 on the successful inaugural summer of alumni- ete Mangurian is the 10th head football coach since there, the methods to achieve that goal. The goal will happen if sponsored internships. I came to Columbia as a freshman in 1967. (Yes, we you do the other things along the way.” were “freshmen” then, not “first-years,” and we even Still, there’s no substitute for the goal, what Mangurian calls 50 Bookshelf wore beanies during Orientation — but that’s a story the “W word.” for another time.) Since then, Columbia has compiled “The bottom line is winning,” he said.