Pro Poor Mobile Capabilities: Service Offering in Latin America and the Caribbean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

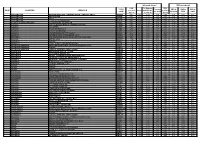

ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR TADIG CODE Calls

Calls made abroad SMS sent abroad Calls To Belgium SMS TADIG To zones SMS to SMS to SMS to ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR received Local and Europe received CODE 2,3 and 4 Belgium EUR ROW abroad (= zone1) abroad 3 AFGHANISTAN AFGHAN WIRELESS COMMUNICATION COMPANY 'AWCC' AFGAW 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN AREEBA MTN AFGAR 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN TDCA AFGTD 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN ETISALAT AFGHANISTAN AFGEA 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 1 ALANDS ISLANDS (FINLAND) ALANDS MOBILTELEFON AB FINAM 0,08 0,29 0,29 2,07 0,00 0,09 0,09 0,54 2 ALBANIA AMC (ALBANIAN MOBILE COMMUNICATIONS) ALBAM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA VODAFONE ALBVF 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA EAGLE MOBILE SH.A ALBEM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA DJEZZY (ORASCOM) DZAOT 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA ATM (MOBILIS) (EX-PTT Algeria) DZAA1 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA WATANIYA TELECOM ALGERIE S.P.A. -

The Town of Willington's Permitting System Requires Applicants to Have

Town of Willington Land Use and Building Department Willington Town Office Building 40 Old Farms Road Willington, CT 06279 The Town of Willington’s permitting system requires applicants to have a valid email address to apply for permits, receive approvals and other permit documents. This is also the primary contact point for communicating to an applicant regarding building inspections or additional information needed during the permit review process. This email address not only allows the applicant to communicate directly with department staff, but it also allows Town staff to transmit permit documents, approvals and certificates directly to the applicant. The Town of Willington does not mail paper copies of permit approvals and/or certificates. If you do not have an email address, but do have a mobile phone that is capable of receiving text messages, that can be used in lieu of a traditional email address.. Every wireless carrier in America allows emails to be sent as text messages to a mobile phone (standard text messaging rates will apply). The only information you need is the phone number and the wireless carrier. The mobile email address for each carrier is listed below: T-Mobile [10-digit phone number]@tmomail.net Example: [email protected] AT&T Wireless (formerly Cingular) [10-digit phone number]@txt.att.net Example: [email protected] Verizon [10-digit-number]@vtext.com Example: [email protected] Boost Mobile [10-digit phone number] @sms.myboostmobile.com Example: [email protected] Cricket Wireless [10-digit phone number]@sms.mycricket.com Example: [email protected] Town of Willington Land Use and Building Department Willington Town Office Building 40 Old Farms Road Willington, CT 06279 Sprint [10-digit phone number]@messaging.sprintpcs.com Example: [email protected] Tracfone or Straight Talk The address varies. -

PUERTO RICO II!!JJI/I/8III' VERDE~ Table 1 Certified Carriers1

ESTADO LIBREASOCIADO DE PUERTO RICO JUNTA REGLAMENTADORA DE TELECOMUNICACIONES DE PUERTO RICO Oficina de Ia Presidenta September 28, 2012 Marlene H. Dortch Office of the Secretary Federal Communications Commission 445 1ih Street, SW Washington, DC 20554 Karen Majcher Vice President, High Cost and Low Income Division Universal Service Administrative Company 2000 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036 Re: WC Docket No. 10-90 Annual State Certification of Support Pursuant to 47 C.F.R. §54.314 To Whom It May Concern: The Telecommunications Regulatory Board of Puerto Rico hereby certifies to the Federal Communications Commission and the Universal Service Administrative Company that the telecommunications carriers listed below in Table 1 are eligible to receive federal high cost support for the program years cited. Specifically, the Telecommunications Regulatory Board of Puerto Rico certifies for the carriers listed, that all federal high-cost support provided to such carriers within Puerto Rico was used in the preceding calendar year (2011) and will be used in the coming calendar year (2013) only for the provision, maintenance, and upgrading of facilities and services for which the support is intended. 500 AVE. ROBERTO H. TODD (PDA.l8 SANTURCE) SAN JUAN, P.R. 00907-3941 PUERTO RICO II!!JJI/I/8III' VERDE~ Table 1 Certified Carriers1 Study Area Name Study Area Code PRTC- Central (PRTC) 633200 Puerto Rico Tel Co (PRTC) 633201 Centennial Puerto Rico Operations Corp. (AT&T) 639001 Suncom Wireless Puerto Rico Operating Co. LLC 639003 (T-Mobile) Cingular Wireless (AT&T) 639005 Puerto Rico Telecom Company D/B/A Verizon 639006 Wireless Puerto (Claro) PR Wireless Inc. -

As Filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on February 27, 2009

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on February 27, 2009 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Form 20-F ý ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2008 Commission file number 001-14540 Deutsche Telekom AG (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) Federal Republic of Germany (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 140, 53113 Bonn, Germany (Address of Registrant’s Principal Executive Offices) Guido Kerkhoff Deutsche Telekom AG Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 140, 53113 Bonn, Germany +49-228-181-0 [email protected] (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered American Depositary Shares, each representing New York Stock Exchange one Ordinary Share Ordinary Shares, no par value New York Stock Exchange* Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: NONE (Title of Class) Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: NONE (Title of Class) Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report: Ordinary Shares, no par value: 4,361,319,993 (as of December 31, 2008) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

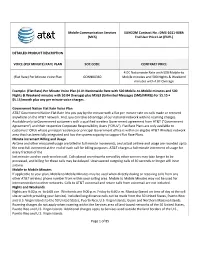

MCS AT&T Mobility User Rates

Mobile Communication Services SUNCOM Contract No.: DMS-1011-008A (MCS) End User Price List (EUPL) DETAILED PRODUCT DESCRIPTION VOICE (PER MINUTE) RATE PLAN SOC CODE CONTRACT PRICE 4.0¢ Nationwide Rate with 500 Mobile-to (Flat Rate) Per Minute Voice Plan ODNN00360 Mobile minutes and 500 Nights & Weekend minutes with 4.0¢ Overage Example: (Flat Rate) Per Minute Voice Plan (4.0¢ Nationwide Rate with 500 Mobile-to-Mobile minutes and 500 Nights & Weekend minutes with $0.04 Overage) plus MSG3 (Unlimited Messages (SMS/MMS)) for $5.15 = $5.15/month plus any per minute voice charges. Government Nation Flat Rate Voice Plan AT&T Government Nation Flat Rate lets you pay by the minute with a flat per-minute rate on calls made or received anywhere on the AT&T network. And, you can take advantage of our national network with no roaming charges. Available only to Government customers with a qualified wireless Government agreement from AT&T (“Government Agreement”) and their respective Corporate Responsibility Users (“CRUs”). Flat Rate Plans are only available to customers’ CRUs whose principal residence or principal Government office is within an eligible AT&T Wireless network area that has been fully integrated and has the system capacity to support Flat Rate Plans. Minute Increment Billing and Usage Airtime and other measured usage are billed in full-minute increments, and actual airtime and usage are rounded up to the next full increment at the end of each call for billing purposes. AT&T charges a full-minute increment of usage for every fraction of the last minute used on each wireless call. -

Inmarsat GSM 2 WAY Worldwide

Worldwide --- Inmarsat GSM 2 WAY Worldwide --- Iridium GSM 2 WAY Worldwide --- Maritime Communications Partner AS (MCP network) GSM/Satellite 2 WAY Worldwide --- Thuraya GSM 2 WAY Asia-Pacific Afghanistan Afghan Wireless Communications Co. (AWCC) GSM 2 WAY Asia-Pacific Afghanistan Etisalat Afghanistan GSM 2 WAY Asia-Pacific Afghanistan MTN Afghanistan GSM 2 WAY Asia-Pacific Afghanistan TDCA GSM 2 WAY Eastern Europe Albania Eagle Mobile GSM 2 WAY Eastern Europe Albania Plus Communication Sh.A. GSM 2 WAY Eastern Europe Albania Vodafone (Albania) GSM 2 WAY Africa Algeria Algerie Telecom Mobile Mobilis GSM 2 WAY Africa Algeria Orascom Algeria GSM 2 WAY Africa Algeria Wataniya Telecom (Nedjma) GSM 2 WAY Asia-Pacific American Samoa Blue Sky Communications GSM 2 WAY Africa Angola Movicel CDMA/GSM 2 WAY Africa Angola Unitel Angola GSM/W-CDMA 2 WAY Americas Anguilla Cable & Wireless Anguilla GSM 2 WAY Americas Anguilla Digicel Anguilla GSM 2 WAY Americas Anguilla Weblinks GSM 2 WAY Americas Antigua APUA GSM 2 WAY Americas Antigua Cable & Wireless Antigua GSM 2 WAY Americas Antigua Digicel Antigua GSM 2 WAY Americas Argentina Claro Argentina (AMX) GSM/W-CDMA 2 WAY Americas Argentina Telecom Personal Argentina GSM/W-CDMA 2 WAY Americas Argentina Telefonica Moviles Argentina GSM/W-CDMA 2 WAY Eastern Europe Armenia Armentel GSM 2 WAY Eastern Europe Armenia Karabakh Telecom GSM 2 WAY Eastern Europe Armenia Orange Armenia GSM/W-CDMA 2 WAY Eastern Europe Armenia Vivacell (K-Telecom) GSM 2 WAY Americas Aruba Digicel Aruba W-CDMA 2 WAY Americas Aruba DTH -

Merger of AT&T Inc. and Centennial Communications Corp. Description

FCC Form 603 Exhibit 1 Merger of AT&T Inc. and Centennial Communications Corp. Description of Transaction, Public Interest Showing and Related Demonstrations Filed with the Federal Communications Commission November 21, 2008 FCC Form 603 Exhibit 1 INTRODUCTION AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Commission should swiftly approve the transfer of control of the authorizations and spectrum leases held by Centennial Communications Corp. (“Centennial”) to AT&T Inc. (“AT&T”). This transaction will advance the public interest by enhancing telecommunications services in the rural areas and small cities that make up most of Centennial’s service area. These include parts of six states in the Midwest and South, plus the U.S. Virgin Islands, where Centennial provides wireless service, and Puerto Rico, where Centennial provides both wireless and wireline broadband service. By becoming a part of AT&T, Centennial will gain access to expertise and resources, which will allow it to serve these communities even better than it does now. The transaction also will enhance disaster preparedness and result in significant cost savings. These advances for consumers in rural areas and small cities and the other public interest benefits that will flow from this transaction can be achieved without raising any competitive concerns. The transaction will give Centennial’s wireless customers access to the full range of capabilities available on AT&T’s network, which covers more than 290 million people in 13,000 communities in the United States. Centennial’s wireless customers thus will enjoy: a wider variety of rate plans; a more robust set of data services; an expanded scope for mobile-to-mobile calling without using monthly minutes; rollover minutes; additional prepaid offerings; expanded choice of handsets with advanced services capabilities; an open applications policy; enhanced international roaming; opportunities to obtain discounts for wireless/wireline bundles; and, for customers with dual-mode phones, free access to Wi-Fi hotspots at more than 17,000 locations across the country. -

Syzmail/Z V3 Installation and Users Guide

Syzygy Incorporated SyzMAILz Version 2 [Version 3.] November 23, 2019 [Installation and User’s Guide] z/OS based eMail and SMS/Text automation and general API SyzMAIL/z - Installation and User’s Guide Page i SyzMAILz Version 2 Revision History Version Date Revision Description 3.0 11/23/2019 New support for attachments of both JES sysout (ATTJES=) and any other (sequential or PDS member (not entire PDS)) (ATTACH=DSN=) cataloged dataset. Any number of datasets are supported. Also support for datasets that are requested, but don’t happen to exist at the moment of the mail being sent New SYZEMAIL token to allow other addresspaces to “NOT” create mail if the email process is either not licensed or not available. Multiple parms are supplied to allow the site to specify the type of support for this token and how it is interpreted. See the other products which use SyzEMAIL/z for more information. New interface for output creation reducing overhead, space necessary providing better speed. New ESTAEx support for SyzEMAIL/z 2.0 11/23/2014 New support for HTML email New support for wider range of information inside Email and SMS packages New command DBUGPKG which controls console message display of package location information New Command SENTMSG which controls console message display of “email sent to:xxxxxx” messages New MAXLINES command to control the maximum size of an email package to be sent (default 1000 lines) General code changes for speed and reduction of memory usage and CPU resources consumed by SyzMAIL/z 1.1a 2/28/2014 Added SMTPCLASS and SMTPNAME parameters for sites that might not use the IBM defaults (class=B and SMTP=SMTP) Altered expiration checking code to be not quite so intrusive. -

SMS Coverage

7/26/2018 Centro De Mensajes :: Send Single SMS SMS Coverage Covering 651 Operators in 228 Countries. Country Operator Cost Comments Afghan Wireless Communication Company 0.0108 Dynamic Alphanumeric (AWCC) Afghanistan (+93) Roshan 0.0105 Alpha Sender Only Afghanistan (+93) MTN Afghanistan 0.0077 Senders are being Replaced Afghanistan (+93) Etisalat Afghanistan 0.0286 Dynamic Alphanumeric Afghanistan (+93) Salaam Afghan Telecom 0.0101 Dynamic Alphanumeric Afghanistan (+93) Albania Telekom Albania 0.0108 Dynamic Alphanumeric (+355) Albania Vodafone Albania 0.0116 Dynamic Alphanumeric (+355) Albania Eagle Mobile 0.0093 Dynamic Alphanumeric (+355) Algeria Algerie Telecom (Mobilis) 0.0178 Dynamic Alphanumeric (+213) Algeria Orascom Telecom (Djezzy) 0.0101 Dynamic Alphanumeric (+213) Algeria Ooredoo Algeria 0.0155 Dynamic Alphanumeric (+213) American Blue Sky Communications 0.0657 Dynamic Alphanumeric Samoa (+1684) Andorra Andorra Telecom (Servei De Tele. DAndorra) 0.0077 Dynamic Alphanumeric (+376) Angola Unitel Angola 0.0101 Dynamic Alphanumeric (+244) Angola Movicel Angola 0.0139 Dynamic Alphanumeric (+244) Anguilla Weblinks 0.0302 Dynamic Alphanumeric (+1264) Anguilla Wireless Ventures Anguilla (Digicel) 0.0302 Dynamic Alphanumeric (+1264) Anguilla Cable & Wireless Anguilla 0.0131 Dynamic Alphanumeric (+1264) Antigua and APUA PCS 0.0232 Dynamic Alphanumeric Barbuda (+1268) Antigua and FLOW Antigua (LIME - CWC) 0.0302 Dynamic Alphanumeric Barbuda (+1268) Antigua and Digicel Antigua 0.0099 Dynamic Alphanumeric Barbuda (+1268) Argentina Nextel -

Federal Communications Commission DA 14-1862 Before

Federal Communications Commission DA 14-1862 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 ) In the Matter of ) ) Implementation of Section 6002(b) of the ) WT Docket No. 13-135 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 ) ) Annual Report and Analysis of Competitive ) Market Conditions With Respect to Mobile ) Wireless, Including Commercial Mobile Services ) SEVENTEENTH REPORT Adopted: December 18, 2014 Released: December 18, 2014 By the Chief, Wireless Telecommunications Bureau: TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. COMPETITIVE DYNAMICS WITHIN THE INDUSTRY ................................................................ 10 A. Service Providers ............................................................................................................................ 11 1. Facilities-Based Providers ....................................................................................................... 11 2. Resale and MVNO Providers ................................................................................................... 15 3. Other Providers ........................................................................................................................ 17 B. Connections, Net Additions, Churn ................................................................................................ 19 1. Subscribers and Total Connections, and Net Additions -

Public Relations Practices in Puerto Rico: an Exploratory Qualitative Study Delia R

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2007 Public relations practices in Puerto Rico: An exploratory qualitative study Delia R. Jourde University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Jourde, Delia R., "Public relations practices in Puerto Rico: An exploratory qualitative study" (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2233 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Public Relations Practices in Puerto Rico: An Exploratory Qualitative Study by Delia R. Jourde A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Mass Communications College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Derina R. Holtzhausen, Ph.D. Kimberly Golombisky, Ph.D. Kenneth C. Killebrew, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 5, 2007 Keywords: Public Relations, Communications, U.S. Commonwealth, Culture, Case Study © Copyright 2007, Delia R. Jourde Dedication First, I would like to honor the great women in my family for being my inspiration and source of strength. Beginning with my grandmother, my aunt/godmother, and in particular my mother. For their powerful sense of self, commitment to higher education, and fantastic sense of humor. I thank you for everything mom. I would also like to thank the men in life. -

Form-20-F 2007

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on February 28, 2008 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Form 20-F È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2007 Commission file number 001-14540 Deutsche Telekom AG (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) Federal Republic of Germany (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 140, 53113 Bonn, Germany (Address of Registrant’s Principal Executive Offices) Guido Kerkhoff Chief Accounting Officer Deutsche Telekom AG Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 140, 53113 Bonn, Germany +49-228-181-0 [email protected] (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered American Depositary Shares, each representing New York Stock Exchange one Ordinary Share Ordinary Shares, no par value New York Stock Exchange* Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: NONE (Title of Class) Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: NONE (Title of Class) Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report: Ordinary Shares, no par value: 4,361,297,603 (as of December 31, 2007) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act.