Rap and Hip-Hop Outside the Usa Edited by Tony Mitchell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Concert Hall As a Medium of Musical Culture: the Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19Th Century

The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century by Darryl Mark Cressman M.A. (Communication), University of Windsor, 2004 B.A (Hons.), University of Windsor, 2002 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Darryl Mark Cressman 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Darryl Mark Cressman Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) Title of Thesis: The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century Examining Committee: Chair: Martin Laba, Associate Professor Andrew Feenberg Senior Supervisor Professor Gary McCarron Supervisor Associate Professor Shane Gunster Supervisor Associate Professor Barry Truax Internal Examiner Professor School of Communication, Simon Fraser Universty Hans-Joachim Braun External Examiner Professor of Modern Social, Economic and Technical History Helmut-Schmidt University, Hamburg Date Defended: September 19, 2012 ii Partial Copyright License iii Abstract Taking the relationship -

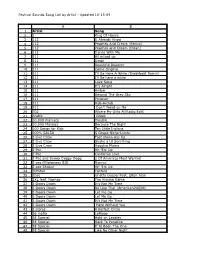

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Radio 2 Paradeplaat Last Change Artiest: Titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley

Radio 2 Paradeplaat last change artiest: titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley Moody Blue 10 2 David Dundas Jeans On 15 3 Chicago Wishing You Were Here 13 4 Julie Covington Don't Cry For Me Argentina 1 5 Abba Knowing Me Knowing You 2 6 Gerard Lenorman Voici Les Cles 51 7 Mary MacGregor Torn Between Two Lovers 11 8 Rockaway Boulevard Boogie Man 10 9 Gary Glitter It Takes All Night Long 19 10 Paul Nicholas If You Were The Only Girl In The World 51 11 Racing Cars They Shoot Horses Don't they 21 12 Mr. Big Romeo 24 13 Dream Express A Million In 1,2,3, 51 14 Stevie Wonder Sir Duke 19 15 Champagne Oh Me Oh My Goodbye 2 16 10CC Good Morning Judge 12 17 Glen Campbell Southern Nights 15 18 Andrew Gold Lonely Boy 28 43 Carly Simon Nobody Does It Better 51 44 Patsy Gallant From New York to L.A. 15 45 Frankie Miller Be Good To Yourself 51 46 Mistral Jamie 7 47 Steve Miller Band Swingtown 51 48 Sheila & Black Devotion Singin' In the Rain 4 49 Jonathan Richman & The Modern Lovers Egyptian Reggae 2 1978 11 Chaplin Band Let's Have A Party 19 1979 47 Paul McCartney Wonderful Christmas time 16 1984 24 Fox the Fox Precious little diamond 11 52 Stevie Wonder Don't drive drunk 20 1993 24 Stef Bos & Johannes Kerkorrel Awuwa 51 25 Michael Jackson Will you be there 3 26 The Jungle Book Groove The Jungle Book Groove 51 27 Juan Luis Guerra Frio, frio 51 28 Bis Angeline 51 31 Gloria Estefan Mi tierra 27 32 Mariah Carey Dreamlover 9 33 Willeke Alberti Het wijnfeest 24 34 Gordon t Is zo weer voorbij 15 35 Oleta Adams Window of hope 13 36 BZN Desanya 15 37 Aretha Franklin Like -

'What Ever Happened to Breakdancing?'

'What ever happened to breakdancing?' Transnational h-hoy/b-girl networks, underground video magazines and imagined affinities. Mary Fogarty Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Interdisciplinary MA in Popular Culture Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © November 2006 For my sister, Pauline 111 Acknowledgements The Canada Graduate Scholarship (SSHRC) enabled me to focus full-time on my studies. I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to my committee members: Andy Bennett, Hans A. Skott-Myhre, Nick Baxter-Moore and Will Straw. These scholars have shaped my ideas about this project in crucial ways. I am indebted to Michael Zryd and Francois Lukawecki for their unwavering kindness, encouragement and wisdom over many years. Steve Russell patiently began to teach me basic rules ofgrammar. Barry Grant and Eric Liu provided comments about earlier chapter drafts. Simon Frith, Raquel Rivera, Anthony Kwame Harrison, Kwande Kefentse and John Hunting offered influential suggestions and encouragement in correspondence. Mike Ripmeester, Sarah Matheson, Jeannette Sloniowski, Scott Henderson, Jim Leach, Christie Milliken, David Butz and Dale Bradley also contributed helpful insights in either lectures or conversations. AJ Fashbaugh supplied the soul food and music that kept my body and mind nourished last year. If AJ brought the knowledge then Matt Masters brought the truth. (What a powerful triangle, indeed!) I was exceptionally fortunate to have such noteworthy fellow graduate students. Cole Lewis (my summer writing partner who kept me accountable), Zorianna Zurba, Jana Tomcko, Nylda Gallardo-Lopez, Seth Mulvey and Pauline Fogarty each lent an ear on numerous much needed occasions as I worked through my ideas out loud. -

SEM Awards Honorary Memberships for 2020

Volume 55, Number 1 Winter 2021 SEM Awards Honorary Memberships for 2020 Jacqueline Cogdell DjeDje Edwin Seroussi Birgitta J. Johnson, University of South Carolina Mark Kligman, UCLA If I could quickly snatch two words to describe the career I first met Edwin Seroussi in New York in the early 1990s, and influence of UCLA Professor Emeritus Jacqueline when I was a graduate student and he was a young junior Cogdell DjeDje, I would borrow from the Los Angeles professor. I had many questions for him, seeking guid- heavy metal scene and deem her the QUIET RIOT. Many ance on studying the liturgical music of Middle Eastern who know her would describe her as soft spoken with a Jews. He greeted me warmly and patiently explained the very calm and focused demeanor. Always a kind face, and challenges and possible directions for research. From that even she has at times described herself as shy. But along day and onwards Edwin has been a guiding force to me with that almost regal steadiness and introspective aura for Jewish music scholarship. there is a consummate professional and a researcher, teacher, mentor, administrator, advocate, and colleague Edwin Seroussi was born in Uruguay and immigrated to who is here to shake things up. Beneath what sometimes Israel in 1971. After studying at Hebrew University he appears as an unassuming manner is a scholar of excel- served in the Israel Defense Forces and earned the rank lence, distinction, tenacity, candor, and respect who gently of Major. After earning a Masters at Hebrew University, he pushes her students, colleagues, and community to dig went to UCLA for his doctorate. -

John Zorn Artax David Cross Gourds + More J Discorder

John zorn artax david cross gourds + more J DiSCORDER Arrax by Natalie Vermeer p. 13 David Cross by Chris Eng p. 14 Gourds by Val Cormier p.l 5 John Zorn by Nou Dadoun p. 16 Hip Hop Migration by Shawn Condon p. 19 Parallela Tuesdays by Steve DiPo p.20 Colin the Mole by Tobias V p.21 Music Sucks p& Over My Shoulder p.7 Riff Raff p.8 RadioFree Press p.9 Road Worn and Weary p.9 Bucking Fullshit p.10 Panarticon p.10 Under Review p^2 Real Live Action p24 Charts pJ27 On the Dial p.28 Kickaround p.29 Datebook p!30 Yeah, it's pink. Pink and blue.You got a problem with that? Andrea Nunes made it and she drew it all pretty, so if you have a problem with that then you just come on over and we'll show you some more of her artwork until you agree that it kicks ass, sucka. © "DiSCORDER" 2002 by the Student Radio Society of the Un versify of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circulation 17,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN ilsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money ordei payable to DiSCORDER Magazine, DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the December issue is Noven ber 13th. Ad space is available until November 27th and can be booked by calling Steve at 604.822 3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. -

The BG News April 15, 1999

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-15-1999 The BG News April 15, 1999 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 15, 1999" (1999). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6484. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6484 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ■" * he BG News Women rally to 'take back the night' sexual assault. istration vivors, they will be able to relate her family. By WENDY SUTO Celesta Haras/ti, a resident of buildings, rain to parts of her story, Kissinger "The more I tell my story, the The BG News BG and a W4W member, said the or shine. The said. less shame and guilt I feel," Kissinger said. "For my situa- Women (and some men) will rally is about issues that are con- keynote "When I decided to disclose tion, I'm glad I didn't tell my take to the streets tonight, pro- sidered taboo by society, such as speaker, my sexual abuse to my family, I parents right away because I claiming a public statement in an rape and incest. She has attended Kendel came out of the closet complete- think it would have been a worse attempt to "Take Back the Night" several TBTN marches at the Kissinger, a ly," Kissinger said. -

Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No

Institute for Studies In American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No. 2 Spring 2005 Jungle Jive: Jazz was an integral element in the sound and appearance of animated cartoons produced in Race, Jazz, Hollywood from the late 1920s through the late 1950s.1 Everything from big band to free jazz and Cartoons has been featured in cartoons, either as the by soundtrack to a story or the basis for one. The studio run by the Fleischer brothers took an Daniel Goldmark unusual approach to jazz in the late 1920s and the 1930s, treating it not as background but as a musical genre deserving of recognition. Instead of using jazz idioms merely to color the musical score, their cartoons featured popular songs by prominent recording artists. Fleischer was a well- known studio in the 1920s, perhaps most famous Louis Armstrong in the jazz cartoon I’ll Be Glad When for pioneering the sing-along cartoon with the You’ re Dead, You Rascal You (Fleischer, 1932) bouncing ball in Song Car-Tunes. An added attraction to Fleischer cartoons was that Paramount Pictures, their distributor and parent company, allowed the Fleischers to use its newsreel recording facilities, where they were permitted to film famous performers scheduled to appear in Paramount shorts and films.2 Thus, a wide variety of musicians, including Ethel Merman, Rudy Vallee, the Mills Brothers, Gus Edwards, the Boswell Sisters, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong, began appearing in Fleischer cartoons. This arrangement benefited both the studios and the stars. -

Introduction to Global Music the Center for European

Introduction to Global Music The Center for European Studies (CES) and other Area Studies Centers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill are collaborating with the student-run radio station WXYC in the production of the Global Music Show. This monthly hour-long program features music from a particular area of the world combined with commentary by guest scholars, who discuss the music played in the context of the culture and history of the region that produced it. To support cultural learning, CES has created student listening guides, pre- and post-listening discussion questions, and resource links for each of their Global Music programs. The programs run about one hour, and so listening and discussion would work well for block schedule classes. If your class runs the traditional hour length, you can have the class listen over two periods, and then discuss. Alternatively, you can assign the listening for homework, and hold the discussion during class time. Music can teach us much about a culture that never appears in a textbook. Use these programs and teaching resources to connect your students with European cultures in a dynamic, new way. Encourage students to continue their exploration of Europe through music. Nederhop: Hip Hop from the Netherlands Dan Thornton and Lauren Brenner Pre-Listening Questions Ask students to think about these questions before you listen to the program. Write their answers on the board. 1. What do you think of first when you think of the Netherlands? 2. In this program, you’re going to hear hip hop by Dutch musicians. -

Hip-Hop & the Global Imprint of a Black Cultural Form

Hip-Hop & the Global Imprint of a Black Cultural Form Marcyliena Morgan & Dionne Bennett To me, hip-hop says, “Come as you are.” We are a family. Hip-hop is the voice of this generation. It has become a powerful force. Hip-hop binds all of these people, all of these nationalities, all over the world together. Hip-hop is a family so everybody has got to pitch in. East, west, north or south–we come MARCYLIENA MORGAN is from one coast and that coast was Africa. Professor of African and African –dj Kool Herc American Studies at Harvard Uni- versity. Her publications include Through hip-hop, we are trying to ½nd out who we Language, Discourse and Power in are, what we are. That’s what black people in Amer- African American Culture (2002), ica did. The Real Hiphop: Battling for Knowl- –mc Yan1 edge, Power, and Respect in the LA Underground (2009), and “Hip- hop and Race: Blackness, Lan- It is nearly impossible to travel the world without guage, and Creativity” (with encountering instances of hip-hop music and cul- Dawn-Elissa Fischer), in Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century ture. Hip-hop is the distinctive graf½ti lettering (ed. Hazel Rose Markus and styles that have materialized on walls worldwide. Paula M.L. Moya, 2010). It is the latest dance moves that young people per- form on streets and dirt roads. It is the bass beats DIONNE BENNETT is an Assis- mc tant Professor of African Ameri- and styles of dress at dance clubs. It is local s can Studies at Loyola Marymount on microphones with hands raised and moving to University. -

The Construction of Hip Hop Identities in Finnish Rap Lyrics Through English and Language Mixing

UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ ”BUUZZIA, BUDIA JA HYVÄÄ GHETTOBOOTYA” - THE CONSTRUCTION OF HIP HOP IDENTITIES IN FINNISH RAP LYRICS THROUGH ENGLISH AND LANGUAGE MIXING A Pro Gradu Thesis in English by Elina Westinen Department of Languages 2007 HUMANISTINEN TIEDEKUNTA KIELTEN LAITOS Elina Westinen ”BUUZZIA, BUDIA JA HYVÄÄ GHETTOBOOTYA” - THE CONSTRUCTION OF HIP HOP IDENTITIES IN FINNISH RAP LYRICS THROUGH ENGLISH AND LANGUAGE MIXING Pro gradu –tutkielma Englannin kieli Joulukuu 2007 141 sivua Englannin kielen rooli ja asema maailmankielenä on kiistaton, ja Suomessakin englannin kieltä käytetään monilla eri aloilla. Juuriltaan amerikkalaisesta hip hop – kulttuuristakin on viime vuosina kasvanut globaali nuorisokulttuuri, joka on saavuttanut pysyvän aseman Suomessa. Tämän tutkimuksen tarkoituksena on selvittää, miten hip hop –identiteetti rakentuu suomalaisissa rap–lyriikoissa. Päätavoitteena on tutkia, millainen hip hop –identiteetti muodostuu lyriikoiden englannin kielen ja kielten sekoittumisen (suomi ja englanti) kautta. Tutkimuksen aineistona käytetään kolmen eri hip hop –artistin ja – ryhmän (Cheek, Sere & SP ja Kemmuru) lyriikoita 2000-luvulta. Niiden pääkieli on suomi, mutta kaikissa kappaleissa on myös englanninkielisiä elementtejä. Sanojen tarkkojen alkuperien sekä muun tiedon selvittämiseksi olen tarvittaessa konsultoinut itse artisteja. Analyysissä identiteetin käsitetään rakentuvan osaltaan kielen avulla. Identiteetti rakentuu diskursseissa, ja se on muuttuva ja monitahoinen. Aineiston analyysissä kielenvaihtelu ymmärretään joko a) kielten sekoittumisena, josta syntyy kokonaan uusi kieli/kielellinen tyyli tai b) koodinvaihtona, joka on merkityksellistä diskurssin paikallisella tasolla. Tulokset osoittavat, että rap–lyriikoissa pikemminkin sekoitetaan suomen ja englannin kieltä (language mixing) kuin vaihdetaan koodia. Näin ollen muodostuu uusi, suomalaisille rap–lyriikoille ominainen kieli ja tyyli. Usein hip hop -englannin sanoja ja fraaseja taivutetaan suomen ortografian, morfologian tai molempien mukaan. Joskus lyriikoissa esiintyy myös ns. -

150Futures Live Syllabus

#150Futures Live Syllabus Ainsworth, Lynn. “They dance their troubles away.” Toronto Star [Toronto] 1 Jan 1985: 6. Barr, Greg. “Rap ground disappoints 500 teenage fans.” Ottawa Citizen [Ottawa] 14 August 1989: A16. Barr, Greg. “Maestro, if you please…” Ottawa Citizen [Ottawa] 08 June 1990: C3. Campbell, Mark V. “The Politics of Making Home: Opening Up the Work of Richard Iton in Canadian Hip Hop Context.” Souls 16, no. 3-4 (2014): 269-282. Campbell, Mark V. “Everything’s Connected: A Relationality Remix, A Praxis.” The CLR James Journal (2014). Chamberland, Roger. 2001. “Rap in Canada: Bilingual and Multicultural”. In Global Noise, edited by Tony Mitchell, 306-23. Middleton, CT: Weleyan University Press. Cutler, Cecelia. “Hip-Hop Language in Sociolinguistics and Beyond.” Language and linguistics compass 1, no. 5 (2007): 519-538. Clarke, Sandra, and Philip Hiscock. “Hip-hop in a post-insular community: Hybridity, local language, and authenticity in an online Newfoundland rap group.” Journal of English Linguistics 37, no. 3 (2009): 241- 261. Dimanno, Rosie. “Breakdamcers twirl and jump in quest to become champions.” Toronto Star [Toronto] 27 May 1984: A4. Erskine, Evelyn. “Musical plea says it’s time for rap, reggae to run together.” Ottawa Citizen [Ottawa] 02 Feb 1990: C6. fogarty, Mary. “Breaking expectations: Imagined affinities in mediated youth cultures.” Continuum 26, no. 3 (2012): 449-462. fogarty, Mary. ““Each one, teach one”: b-boying and ageing.” Ageing and Youth Culture: Music, Style, and Identity, London and New York: Berg (53–65) (2012). forman, M. (2000). ‘Represent’: race, space and place in rap music. Popular Music, 19(1), 65-90.