Naraghi Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series Editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University Signale: Modern German Letters, Cultures, and Thought publishes new English- language books in literary studies, criticism, cultural studies, and intellectual history pertaining to the German-speaking world, as well as translations of im- portant German-language works. Signale construes “modern” in the broadest terms: the series covers topics ranging from the early modern period to the present. Signale books are published under a joint imprint of Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library in electronic and print formats. Please see http://signale.cornell.edu/. The Total Work of Art in European Modernism David Roberts A Signale Book Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Ithaca, New York Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library gratefully acknowledge the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the publication of this volume. Copyright © 2011 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writ- ing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2011 by Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roberts, David, 1937– The total work of art in European modernism / David Roberts. p. cm. — (Signale : modern German letters, cultures, and thought) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5023-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Modernism (Aesthetics) 2. -

The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 1-5-2021 The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020 Denali Elizabeth Kemper CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/661 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020 By Denali Elizabeth Kemper Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2020 Thesis sponsor: January 5, 2021____ Emily Braun_________________________ Date Signature January 5, 2021____ Joachim Pissarro______________________ Date Signature Table of Contents Acronyms i List of Illustrations ii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Points of Reckoning 14 Chapter 2: The Generational Shift 41 Chapter 3: The Return of the Repressed 63 Chapter 4: The Power of Nazi Images 74 Bibliography 93 Illustrations 101 i Acronyms CCP = Central Collecting Points FRG = Federal Republic of Germany, West Germany GDK = Grosse Deutsche Kunstaustellung (Great German Art Exhibitions) GDR = German Democratic Republic, East Germany HDK = Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) MFAA = Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Program NSDAP = Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Worker’s or Nazi Party) SS = Schutzstaffel, a former paramilitary organization in Nazi Germany ii List of Illustrations Figure 1: Anonymous photographer. -

WG Sebald and Outsider

Writing from the Periphery: W. G. Sebald and Outsider Art by Melissa Starr Etzler A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Winfried Kudszus, Chair Professor Anton Kaes Professor Anne Nesbet Spring 2014 Abstract Writing from the Periphery: W. G. Sebald and Outsider Art by Melissa Starr Etzler Doctor of Philosophy in German and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Winfried Kudszus, Chair This study focuses on a major aspect of literature and culture in the later twentieth century: the intersection of psychiatry, madness and art. As the antipsychiatry movement became an international intervention, W. G. Sebald’s fascination with psychopathology rapidly developed. While Sebald collected many materials on Outsider Artists and has several annotated books on psychiatry in his personal library, I examine how Sebald’s thought and writings, both academic and literary, were particularly influenced by Ernst Herbeck’s poems. Herbeck, a diagnosed schizophrenic, spent decades under the care of Dr. Leo Navratil at the psychiatric institute in Maria Gugging. Sebald became familiar with Herbeck via the book, Schizophrenie und Sprache (1966), in which Navratil analyzed his patients’ creative writings in order to illustrate commonalities between pathological artistic productions and canonical German literature, thereby blurring the lines between genius and madness. In 1980, Sebald travelled to Vienna to meet Ernst Herbeck and this experience inspired him to compose two academic essays on Herbeck and the semi-fictionalized account of their encounter in his novel Vertigo (1990). -

Fairy Tale Versions~

FAIRY TALES/FOLK TALES Fairy Tales are a type of folktale in which magic plays a great part. Compiled by Sheila Kirven GENERAL Anderson, Hans Christian Steadfast Tin Soldier Juv.A544ste Armstrong, Gerry The magic bagpipe Juv. 788.9 .A735m Browne, Anthony Into the Forest Juv. B882i (Story incorporates elements of familiar tales) Casserley, Anne Roseen Juv. 398.21 .C344r Chapman, Gaynor The Luck Child Juv. 398.21.C466l 1968 De Regniers, Beatrice Little Sister and the Month Brothers Juv. D431Li Schenk The House in the Wood and Other Old Fairy Stories Juv. 398.2.G864h Little Lit: Folklore and Fairy Tale Funnies Juv.398.21.F666 Hennessy, B. G. Once Upon a Time Map Book: Take a Tour Juv.H515o of Six Enchanted Lands (Peter Pan, Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, Jack and then Beanstalk, Aladdin, Snow White) Jacobs, Joseph The buried moon; a tale told by Joseph Jacobs. Juv. 398.21 .J17b Jacobs, Joseph Indian fairy tales Juv.398.2 .J17i 1969 MacDonald, George, The golden key Juv. M135g Matsutani, Miyoko, The crane maiden. Juv. 98.21 .M434c My Storytime Collection of First Favorite tales Juv. 398.2.M995 2002 O’Malley, Kevin Once upon a cool motorcycle dude Juv. O543o (Two classmates try to tell a fairy tale to their class with some imaginative twists to some well-known fairy tale elements!) Oxenbury, Helen. Helen Oxenbury nursery story book. Juv. 398.21 .O98h San Jose, Christine Little Match Girl Juv. 398.21.A544j San Souci, Robert D. White Cat Juv.398.21.SS229w 1990 Singer, Marilyn Follow Follow: A book of Reverso poems Juv.811.54.S617f (Poems -

Appendix: More on Methodology

Appendix: More on Methodology Over the years my fi rst monograph, The Nature of Fascism (1991), has been charged by some academic colleagues with essentialism, reductionism, ‘revisionism’, a disinterest in praxis or material realities, and even a philosophical idealism which trivializes the human suffering caused by Hitler’s regime. It is thus worth offering the more methodologically self-aware readers, inveterately sceptical of the type of large-scale theorizing (‘metanarration’) that forms the bulk of Part One of this book, a few more paragraphs to substantiate my approach and give it some sort of intellectual pedigree. It can be thought of as deriving from three lines of methodological inquiry – and there are doubtless others that are complementary to them. One is the sophisticated (but inevitably contested) model of concept formation through ‘idealizing abstraction’1 which was elaborated piece-meal by Max Weber when wrestling with a number of the dilemmas which plagued the more epistemologically self-aware academics engaged in the late nineteenth-century ‘Methodenstreit’. This was a confl ict over methodology within the German human sciences that anticipated many themes of the late twentieth-century debate over how humanities disciplines should respond to postmodernism and the critical turn.2 The upshot of this line of thinking is that researchers must take it upon themselves to be as self-conscious as possible in the process of constructing the premises and ‘ideal types’ which shape the investigation of an area of external reality. Nor should they ever lose sight of the purely heuristic nature of their inquiry, and hence its inherently partial, incomplete nature. -

Commonlit | the Pied Piper of Hamelin

Name: Class: The Pied Piper of Hamelin By Robert Browning 1888 Robert Browning (1812-1889) was an English poet and playwright known for his dramatic verse. “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” published in 1888, is a poetic retelling of the German legend from the Middle Ages in which a man is hired to lure rats away from a town with his magic pipe. As you read, take notes on the Piper's actions and motivations. [1] Hamelin town's in Brunswick, By famous Hanover city; The River Weser, deep and wide, Washes its wall on the southern side; [5] A pleasanter spot you never spied; But, when begins my ditty, Almost five hundred years ago, To see townsfolk suffer so From vermin, was a pity. [10] Rats! They fought the dogs, and killed the cats, And bit the babies in the cradles, And ate the cheeses out of the vats, And licked the soup from the cook's own ladles, [15] Split open the kegs of salted sprats,1 "Pied Piper with Children" by Kate Greenaway is in the public Made nests inside men's Sunday hats, domain. And even spoiled the women's chats, By drowning their speaking With shrieking and squeaking [20] In fifty different sharps and flats. 1. a small fish of the herring family 1 At last the people in a body To the Town Hall came flocking: "'Tis clear," cried they, "our Mayor's a noddy;2 And as for our Corporation—shocking [25] To think we buy gowns lined with ermine3 For dolts4 that can't or won't determine What's best to rid us of our vermin! You hope, because you're old and obese, To find in the furry civic robe ease? [30] Rouse up, sirs! Give your brains a racking To find the remedy we're lacking, Or, sure as fate, we'll send you packing!" At this the Mayor and Corporation Quaked with a mighty consternation.5 [35] An hour they sat in council, At length the Mayor broke silence: "For a guilder6 I'd my ermine gown sell, I wish I were a mile hence! It's easy to bid one rack one's brain — [40] I'm sure my poor head aches again I've scratched it so, and all in vain. -

Fairy Tales & Legends: the Novels

Koertge, Ron. Lies, Knives and Girls in Red Dresses (Little Red Riding Hood) Levine, Gail Carson. Fairest (Snow White isn’t the fairest of them all) These are tales that are written in full Lo, Malinda. novel form, with intricately developed Ash (Cinderella) plots and characters. Sometimes the Marillier, Juliet. version is altered, such as taking place in a Wildwood Dancing (The Frog Prince different location or being told through and Twelve Dancing Princesses, set in the eyes of a different character. Transylvania) Anderson, Jodi Lynn. Martin, Rafe. Tiger Lily (Peter Pan) Birdwing (A continuation of Six Swans) Barron, T.A. Masson, Sophie. The Lost Years of Merlin series Serafin (Puss in Boots, only the cat is an Great Tree of Avalon series angel in disguise) Bunce, Elizabeth. McKinley, Robin. A Curse as Dark as Gold (Rumplestiltskin) Beauty (Beauty & the Beast) Coombs, Kate. Spindle’s End (Sleeping Beauty) The Runaway Princess Meyer, Marissa. (A new twist on old tales) Lunar Chronicles (Dystopian fairy tales) Crossley-Holland, Kevin. Meyer, Walter Dean. Arthur trilogy Amiri & Odette (Swan Lake set in the Projects) Delsol, Wendy. Stork trilogy (Snow Queen) Napoli, Donna Jo. Dokey, Cameron. Beast (Beauty & the Beast, set in Persia, Golden (Rapunzel) told from Beast’s point of view) Beauty Sleep (Sleeping Beauty) Breath (Pied Piper) Donoghue, Emma. Crazy Jack (Jack and the Beanstalk; Kissing the Witch (13 tales loosely Jack’s looking for his dad) connected to each other) The Magic Circle (Hansel & Gretel; the witch’s story) Durst, Sarah Beth. Ice (East of the Sun, West of the Moon) Pearce, Jackson. -

Live to Re-Tell the Tale

Live to Re-tell the Tale.... Select a favourite fairy tale that you would like to re-tell. Then, choose one character from the story who will present the tale from his/her point of view. Consider the following questions as you think about your Re-told Tale: Will the story be different because of the character you have chosen? For example, if that character is a Big Bad Wolf or an Evil Witch, how might you change the story to reflect that character’s take on the story? Will there be added scenes in your tale based on the character you have chosen? For example, if you chose to tell the tale of Cinderella from the Fairy Godmother’s perspective, what might be different about your story (ie., before, during and after the ball?) How will the dialogue in the story be different as it comes from your character? Do you want to make your main character a more modernized, or nicer, or meaner version than in the original tale? What other information do you want to share about your character that might not have been part of the original story? You do not have to rewrite the entire tale, but can write a synopsis of it. (A synopsis is like a summary, that lets the reader or listener know what the whole story is about). Your synopsis can be in point form, in mini paragraphs, or in whatever form you like. You will present your story ORALLY to the group, so you can also think about how your presentation will be different than an entire written story. -

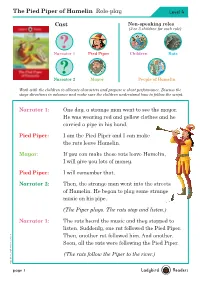

The Pied Piper of Hamelin Role-Play Level 4

The Pied Piper of Hamelin Role-play Level 4 Cast Non-speaking roles (2 or 3 children for each role) ? Narrator 1 Pied Piper Children Rats ? Narrator 2 Mayor People of Hamelin Work with the children to allocate characters and prepare a short performance. Discuss the stage directions in advance and make sure the children understand how to follow the script. Narrator 1: One day, a strange man went to see the mayor. He was wearing red and yellow clothes and he carried a pipe in his hand. Pied Piper: I am the Pied Piper and I can make the rats leave Hamelin. Mayor: If you can make these rats leave Hamelin, I will give you lots of money. Pied Piper: I will remember that. Narrator 2: Then, the strange man went into the streets of Hamelin. He began to play some strange music on his pipe. (The Piper plays. The rats stop and listen.) Narrator 1: The rats heard the music and they stopped to listen. Suddenly, one rat followed the Pied Piper. Then, another rat followed him. And another. Soon, all the rats were following the Pied Piper. (The rats follow the Piper to the river.) Copyright © LadybirdCopyright Books Ltd, 2018 page 1 The Pied Piper of Hamelin Role-play Level 4 Narrator 2: The Pied Piper walked toward the river. He was still playing the strange music on his pipe. The rats followed him and they all jumped into the river. And that was the end of the rats in Hamelin. (The Pied Piper returns to the mayor.) Narrator 1: The Pied Piper went back to see the mayor. -

Fairy Tales and Political Socialization

FAIRY TALES AND POLITICAL SOCIALIZATION by Mehrdad Faiz Samadzadeh A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Curriculum, Teaching & Leadership University of Toronto Ontario Institute for Studies in Education © Copyright by Mehrdad Faiz Samadzadeh 2018 FAIRY TALES AND POLITICAL SOCIALIZATION Mehrdad Faiz Samadzadeh Doctor of Philosophy Department of Curriculum, Teaching & Leadership Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2018 Abstract The concept of childhood is one of the many facets of modernity that entered Western consciousness in the seventeenth century. It emanated from the historical mutations of the post-Renaissance era that set in motion what Norbert Elias calls the civilizing process, one that spawned a repressive mode of socialization in tandem with the cultural and ideological hegemony of the new power elite. Accordingly, childhood became a metaphor for oppression targeting not only children, but also women, the underclass, the social outcast, and the colonized as they all were deemed “incompletely human”. From mid-nineteenth century on, however, childhood began to evince a liberating potential in tandem with the changing direction of modern Western civilization. This ushered in an alternative concept of childhood inspired by the shared characteristics between the medieval and modern child that finds expression in the works of distinguished literary figures of the Victorian era. What followed was an entire movement towards the recognition of children’s rights and status that set the context for the growing interest in childhood as a subject of historical inquiry in the twentieth century. This conceptual vicissitude of childhood is central to the present thesis which I pursue in relation to the literary genre of fairy tale. -

Deconceptualizing Artists' Rights

Deconceptualizing Artists’ Rights STEVEN G. GEY* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 38 II. THE NEW CASE AGAINST MORAL RIGHTS STATUTES ........................................... 41 A. The Theory and Justification of Moral Rights Protection .......................... 42 B. The Pragmatic Objections to Moral Rights ............................................... 45 1. Society’s Interest in Destroying Art .................................................... 46 2. Society’s Interest in Favoring Curatorial Decisions About Art ............................................................................................ 49 3. Society’s Interest in Allowing Others To Modify an Artist’s Work ................................................................................. 52 4. Society’s Interest in Recognizing Multiple Authorship ....................... 53 5. The Failure of Pragmatic Arguments Against Moral Rights .............. 54 III. MORAL RIGHTS AND THE END OF ART: THE UNEASY RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ART THEORY AND THE LAW REGARDING ART .................................................................................................. 55 A. The End of Art or the Proliferation of Art? ................................................ 56 B. The End of Art and Destruction-as-Artistic-Creation ................................ 62 C. Reconceptualizing Moral Rights Statutes .................................................. 67 IV. WHY ART (AND ARTISTS) STILL -

March 1923) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 3-1-1923 Volume 41, Number 03 (March 1923) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 41, Number 03 (March 1923)." , (1923). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/699 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ETU D E ,MUS I C MAGAZINE ! MARCH 19 23 25 cents a Copy Theodore Presser Co. $2.00 a Year Philadelphia, Pa. PRESSER’S MUSICAL MAGAZINE New Music Book Publications Presenting Exceptional New Material For l MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE MUSIC STUDENT,^ AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. Teachers, Students, Performers and Music Lovers 2gS3H&'S£SKt EntCrephUadc,Cp°hnia/P:.S, “ieA«6if &3. UtC' °’ * Copyright, 1922, by Theodore Presser Co., for U. S. A. and Great Britain 1712 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. Printed in the United States of America FROM THE FAR EAST PLAYER’S BOOK EIGHT SONGS FROM GREEN TIMBER Lyrics by Charles O. Roos The World of Music U\tr& iHflWwt WOODSY CORNER TALES AND TUNES sssssm £L For Little Piano Players ISSEIS mmst mmm ALBUM OF TRANSCRIPTIONS BILBRO’S KINDERGARTEN JUNIOR COLLECTION of ANTHEMS BOOK By H.