The Day Custody Program: Second Year Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geological Timeline

Geological Timeline In this pack you will find information and activities to help your class grasp the concept of geological time, just how old our planet is, and just how young we, as a species, are. Planet Earth is 4,600 million years old. We all know this is very old indeed, but big numbers like this are always difficult to get your head around. The activities in this pack will help your class to make visual representations of the age of the Earth to help them get to grips with the timescales involved. Important EvEnts In thE Earth’s hIstory 4600 mya (million years ago) – Planet Earth formed. Dust left over from the birth of the sun clumped together to form planet Earth. The other planets in our solar system were also formed in this way at about the same time. 4500 mya – Earth’s core and crust formed. Dense metals sank to the centre of the Earth and formed the core, while the outside layer cooled and solidified to form the Earth’s crust. 4400 mya – The Earth’s first oceans formed. Water vapour was released into the Earth’s atmosphere by volcanism. It then cooled, fell back down as rain, and formed the Earth’s first oceans. Some water may also have been brought to Earth by comets and asteroids. 3850 mya – The first life appeared on Earth. It was very simple single-celled organisms. Exactly how life first arose is a mystery. 1500 mya – Oxygen began to accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen is made by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) as a product of photosynthesis. -

Capricious Suntime

[Physics in daily life] I L.J.F. (Jo) Hermans - Leiden University, e Netherlands - [email protected] - DOI: 10.1051/epn/2011202 Capricious suntime t what time of the day does the sun reach its is that the solar time will gradually deviate from the time highest point, or culmination point, when on our watch. We expect this‘eccentricity effect’ to show a its position is exactly in the South? e ans - sine-like behaviour with a period of a year. A wer to this question is not so trivial. For ere is a second, even more important complication. It is one thing, it depends on our location within our time due to the fact that the rotational axis of the earth is not zone. For Berlin, which is near the Eastern end of the perpendicular to the ecliptic, but is tilted by about 23.5 Central European time zone, it may happen around degrees. is is, aer all, the cause of our seasons. To noon, whereas in Paris it may be close to 1 p.m. (we understand this ‘tilt effect’ we must realise that what mat - ignore the daylight saving ters for the deviation in time time which adds an extra is the variation of the sun’s hour in the summer). horizontal motion against But even for a fixed loca - the stellar background tion, the time at which the during the year. In mid- sun reaches its culmination summer and mid-winter, point varies throughout the when the sun reaches its year in a surprising way. -

Day-Ahead Market Enhancements Phase 1: 15-Minute Scheduling

Day-Ahead Market Enhancements Phase 1: 15-minute scheduling Phase 2: flexible ramping product Stakeholder Meeting March 7, 2019 Agenda Time Topic Presenter 10:00 – 10:10 Welcome and Introductions Kristina Osborne 10:10 – 12:00 Phase 1: 15-Minute Granularity Megan Poage 12:00 – 1:00 Lunch 1:00 – 3:20 Phase 2: Flexible Ramping Product Elliott Nethercutt & and Market Formulation George Angelidis 3:20 – 3:30 Next Steps Kristina Osborne Page 2 DAME initiative has been split into in two phases for policy development and implementation • Phase 1: 15-Minute Granularity – 15-minute scheduling – 15-minute bidding • Phase 2: Day-Ahead Flexible Ramping Product (FRP) – Day-ahead market formulation – Introduction of day-ahead flexible ramping product – Improve deliverability of FRP and ancillary services (AS) – Re-optimization of AS in real-time 15-minute market Page 3 ISO Policy Initiative Stakeholder Process for DAME Phase 1 POLICY AND PLAN DEVELOPMENT Issue Straw Draft Final June 2018 July 2018 Paper Proposal Proposal EIM GB ISO Board Implementation Fall 2020 Stakeholder Input We are here Page 4 DAME Phase 1 schedule • Third Revised Straw Proposal – March 2019 • Draft Final Proposal – April 2019 • EIM Governing Body – June 2019 • ISO Board of Governors – July 2019 • Implementation – Fall 2020 Page 5 ISO Policy Initiative Stakeholder Process for DAME Phase 2 POLICY AND PLAN DEVELOPMENT Issue Straw Draft Final Q4 2019 Q4 2019 Paper Proposal Proposal EIM GB ISO Board Implementation Fall 2021 Stakeholder Input We are here Page 6 DAME Phase 2 schedule • Issue Paper/Straw Proposal – March 2019 • Revised Straw Proposal – Summer 2019 • Draft Final Proposal – Fall 2019 • EIM GB and BOG decision – Q4 2019 • Implementation – Fall 2021 Page 7 Day-Ahead Market Enhancements Third Revised Straw Proposal 15-MINUTE GRANULARITY Megan Poage Sr. -

Calculating Percentages for Time Spent During Day, Week, Month

Calculating Percentages of Time Spent on Job Responsibilities Instructions for calculating time spent during day, week, month and year This is designed to help you calculate percentages of time that you perform various duties/tasks. The figures in the following tables are based on a standard 40 hour work week, 174 hour work month, and 2088 hour work year. If a recurring duty is performed weekly and takes the same amount of time each week, the percentage of the job that this duty represents may be calculated by dividing the number of hours spent on the duty by 40. For example, a two-hour daily duty represents the following percentage of the job: 2 hours x 5 days/week = 10 total weekly hours 10 hours / 40 hours in the week = .25 = 25% of the job. If a duty is not performed every week, it might be more accurate to estimate the percentage by considering the amount of time spent on the duty each month. For example, a monthly report that takes 4 hours to complete represents the following percentage of the job: 4/174 = .023 = 2.3%. Some duties are performed only certain times of the year. For example, budget planning for the coming fiscal year may take a week and a half (60 hours) and is a major task, but this work is performed one time a year. To calculate the percentage for this type of duty, estimate the total number of hours spent during the year and divide by 2088. This budget planning represents the following percentage of the job: 60/2088 = .0287 = 2.87%. -

How Long Is a Year.Pdf

How Long Is A Year? Dr. Bryan Mendez Space Sciences Laboratory UC Berkeley Keeping Time The basic unit of time is a Day. Different starting points: • Sunrise, • Noon, • Sunset, • Midnight tied to the Sun’s motion. Universal Time uses midnight as the starting point of a day. Length: sunrise to sunrise, sunset to sunset? Day Noon to noon – The seasonal motion of the Sun changes its rise and set times, so sunrise to sunrise would be a variable measure. Noon to noon is far more constant. Noon: time of the Sun’s transit of the meridian Stellarium View and measure a day Day Aday is caused by Earth’s motion: spinning on an axis and orbiting around the Sun. Earth’s spin is very regular (daily variations on the order of a few milliseconds, due to internal rearrangement of Earth’s mass and external gravitational forces primarily from the Moon and Sun). Synodic Day Noon to noon = synodic or solar day (point 1 to 3). This is not the time for one complete spin of Earth (1 to 2). Because Earth also orbits at the same time as it is spinning, it takes a little extra time for the Sun to come back to noon after one complete spin. Because the orbit is elliptical, when Earth is closest to the Sun it is moving faster, and it takes longer to bring the Sun back around to noon. When Earth is farther it moves slower and it takes less time to rotate the Sun back to noon. Mean Solar Day is an average of the amount time it takes to go from noon to noon throughout an orbit = 24 Hours Real solar day varies by up to 30 seconds depending on the time of year. -

2020 – 2021 School Calendar

Anne Arundel County Public Schools Approved by the Board of Education 11/20/19 Key: 24 Schools closed 12 Two-hour early dismissal 27 First/Last day for students Bold calendar type— See explanations below 2020 – 2021 School Calendar August September October November December January S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 27 28 29 30 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 27 28 29 30 31 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 30 31 31 August October December 12 Fall Sports begin. -

Sidereal Time Distribution in Large-Scale of Orbits by Usingastronomical Algorithm Method

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2013): 4.438 Sidereal Time Distribution in Large-Scale of Orbits by usingAstronomical Algorithm Method Kutaiba Sabah Nimma 1UniversitiTenagaNasional,Electrical Engineering Department, Selangor, Malaysia Abstract: Sidereal Time literally means star time. The time we are used to using in our everyday lives is Solar Time.Astronomy, time based upon the rotation of the earth with respect to the distant stars, the sidereal day being the unit of measurement.Traditionally, the sidereal day is described as the time it takes for the Earth to complete one rotation relative to the stars, and help astronomers to keep them telescops directions on a given star in a night sky. In other words, earth’s rate of rotation determine according to fixed stars which is controlling the time scale of sidereal time. Many reserachers are concerned about how long the earth takes to spin based on fixed stars since the earth does not actually spin around 360 degrees in one solar day.Furthermore, the computations of the sidereal time needs to take a long time to calculate the number of the Julian centuries. This paper shows a new method of calculating the Sidereal Time, which is very important to determine the stars location at any given time. In addition, this method provdes high accuracy results with short time of calculation. Keywords: Sidereal time; Orbit allocation;Geostationary Orbit;SolarDays;Sidereal Day 1. Introduction (the upper meridian) in the sky[6]. Solar time is what the time we all use where a day is defined as 24 hours, which is The word "sidereal" comes from the Latin word sider, the average time that it takes for the sun to return to its meaning star. -

Time-Of-Day Brochure

Energy conservation starts with you Time-of-Day Service is one way Tampa Electric is working to Time-of-Day Service reduce the amount of electricity that customers use during peak periods of energy consumption. Reducing the peak for small commercial customers electric demand helps to delay construction of costly additional power plants. Large commercial and industrial customers Voluntary Time-of-Day rates are also available for General Service, Demand and Interruptible Service customers. For more information please call Tampa Electric’s Business & Industry team at (813) 223-0800 (Hillsborough County) (863) 299-0800 (Polk County) 1-888-223-0800 (All other counties and out-of-state) tampaelectric.com • Learn how to save on your monthly electric bill • Manage your energy consumption • For more energy information, visit tampaelectric.com 252.1468 CorpComm 11/14 Time-of-Day Service for small commercial customers The Time-of-Day Rate Heating and air conditioning costs Your electric bill can be affected by when you use electricity, Remember, electric heating and air conditioning systems are and how much you use. With the voluntary Time-of-Day often the largest single energy users at your business. Your Service, small commercial customers will pay less for electricity ability to minimize use of these and other electric equipment used during off-peak hours – but more during periods of during peak hours will determine whether you can benefit peak electricity demand. If you can take advantage of this from Time-of-Day Service. rate, you will be able to save on your electric bill. Typical savings with Time-of-Day Service How the rate works Here’s how to find out whether or not, and how much, you Time-of-Day Service benefits customers who can shift may save with Time-of-Day Service. -

Steuben County Earth Day Sheet - 2021 Earth Day Is April 22, 2021

Steuben County Earth Day Sheet - 2021 Earth Day is April 22, 2021. Care for the earth every day. Got old latex paints to get rid BATH LANDFILL-5632 Turnpike Rd., Bath, NY Chairman of and don’t Mon—Sat, 7:30—3:30 PM Scott VanEtten Here’s your chance to get rid of those know what to ERWIN TRANSFER—622 S. Hamilton St, Painted Post District 1 old chemicals. do? Latex HORNELL TRANSFER—6360 E. Avenue Ext, Hornell Gary D. Swackhamer 2078 Dieter Rd, Wayland Paul E. Van Caeseele Pre-registration is required. based paints WAYLAND TRANSFER - District 2 Check the website or our Facebook ONLY, other Tue—Sat, 7:30—3:30 PM Steven Maio page for more info on how to regis- items will be Hilda T. Lando turned away! District 3 BOOK RECYCLING @ BATH………….JULY 12-17 Robin K. Lattimer TIRE DOLLAR DAYS……….……….…...JUNE 7–12 Kelly H. Fitzpatrick BATH & WAYLAND only District 4 Combined HHW and Shred event in Erwin *LATEX PAINT DAY @ BATH…...….….….AUG 7 John V. Malter. Pick them up or drop them *HOUSEHOLD HAZARDOUS WASTE We’re combining both popular events into one District 5 ERWIN…………………………….…..MAY 15 off. Keep hardcover and day this year. Dispose of your documents and HORNELL………………………..AUGUST 21 Michael Hanna soft covers separate. chemicals in just one trip to Erwin District 6 *SHREDDING EVENTS Brian C. Schu, Esq. Libraries welcome! @ERWIN……………...…..……....…......MAY 15 District 7 @ BATH……………………………………...SEPT 11 Aaron I. Mullen *events run 8 AM—Noon District 8 Jeffrey P. Horton District 9 Secure document Tom Ryan destruction District 10 events to be held Memorial Day……………………..……....MAY 31 Fred Potter at Erwin and Bath Independence Day……………….………...JULY 5 Back by popular demand District 11 this year. -

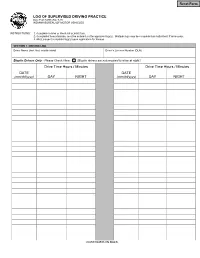

LOG of SUPERVISED DRIVING PRACTICE State Form 54706 (R4 / 7-17) INDIANA BUREAU of MOTOR VEHICLES

LOG OF SUPERVISED DRIVING PRACTICE State Form 54706 (R4 / 7-17) INDIANA BUREAU OF MOTOR VEHICLES INSTRUCTIONS: 1. Complete in blue or black ink or print form. 2. Completed hours/minutes must be entered on the approved log(s). Multiple logs may be completed and attached, if necessary. 3. Must present completed log(s) upon application for license. SECTION 1. DRIVING LOG Driver Name (last, first, middle initial) Driver’s License Number (DLN) Bioptic Drivers Only - Please Check Here: (Bioptic drivers are not required to drive at night.) Drive Time Hours / Minutes Drive Time Hours / Minutes DATE DATE (mm/dd/yyyy) DAY NIGHT (mm/dd/yyyy) DAY NIGHT CONTINUED ON BACK. Driver Name (last, first, middle initial) Driver’s License Number (DLN) Drive Time Hours / Minutes Drive Time Hours / Minutes DATE DATE (mm/dd/yyyy) DAY NIGHT (mm/dd/yyyy) DAY NIGHT SECTION 2. AFFIRMATION AND SIGNATURE I certify that the driver named above has completed fifty (50) hours of supervised driving practice, ten (10) of which included nighttime driving practice, with: a licensed driver education instructor who was working under the direction of a driver training school; a certified driver rehabilitation specialist recognized by the bureau who is employed through a driver rehabilitation program; a validly licensed driver at least twenty-five (25) years of age who is related by blood, marriage or legal status; a validly licensed driver at least twenty-five (25) years of age who is approved by Department of Child Services; or a validly licensed driver at least twenty-one (21) years of age who is the spouse of the driver. -

Physics: Sundial Science

Physics: Sundial Science MAIN IDEA Discover how the sun and its shadow is used to tell time by creating a sundial – an instrument that tracks the position of the sun to indicate time of day. SCIENCE BACKGROUND For centuries humans, have utilized the power of the sun as a light source, to grow food, and to tell time. Ancient civilizations used the sun to understand basic astronomy. By tracking the height of the sun in the sky, these civilizations developed calendars for the year and were able to identify harvesting and planting seasons (fall and spring equinoxes) all by tracking the movement of the sun. This also helped certain civilizations find the Equator, an imaginary circle around the Earth that divides it into two halves, the northern and southern hemisphere. By tracking the sun’s apparent position through the creation of sundials, these ancient civilizations were able to divide the day into morning and afternoon. A sundial is a device used to track time by marking a shadow on its surface as the sun moves. Light travels as a wave, similar to waves in the ocean. Shadows occur when this light wave is blocked by an object, creating a dark silhouette of that object on nearby surfaces as light continues to travel all around the object. Based on where the light source is, and the object that is blocking it, the shadow will look different. This is why for a sundial, the shadow will change throughout the day and even more noticeably throughout the year for the same time of day. -

Teacher Guide to BLOSSOMS Lesson: Geologic Time: the Ticking of Our Planet's 4.6 Billion Year Clock the Earth Is 4.6 Billion Y

Teacher Guide to BLOSSOMS Lesson: Geologic Time: The Ticking of Our Planet’s 4.6 Billion Year Clock The Earth is 4.6 billion years old. That’s a hard number for anyone to conceptualize. What does 4.6 billion look like, and what happened during all those hundreds of millions of years between the formation of our planet and now? This BLOSSOMS lesson will help students conceptualize the enormity of geologic time and learn about important events in Earth’s history. An understanding of geologic time is essential to help students comprehend processes that occur over long time scales, such as evolution, mountain building, plate tectonics, and changes in the Earth’s climate. Thus, in this lesson, students will also learn how geologic time can help explain seemingly incomprehensible processes, like the formation of the Himalayan Mountains from a flat plain to their current height, and the evolution of a tiny group of reptiles into the enormous dinosaurs. Activity 1 – When Did the Dinosaurs Go Extinct?: After seeing Francis stand at three positions along the scale-model of the geologic timeline, students must pick which position represents the time when dinosaurs went extinct. This happened 65 million years ago, which seems like a really long time until you realize that the Earth is 4.6 billion years old. So the correct answer is the closest position to the end of the timeline. Activity 2 – Building your own Geologic Timeline: During this break, students will make their own to-scale geologic timeline in the classroom or a nearby hallway. You will need a measuring tape or a meter stick.