Arthritis & Rheumatism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Procedure Code List Effective Jan. 1, 2020 for Preauthorization for Blue Cross and Blue Shield of New Mexico Medicare Advantage Members Only

Procedure Code List Effective Jan. 1, 2020 for Preauthorization for Blue Cross and Blue Shield of New Mexico Medicare Advantage Members only Beginning Jan. 1, 2020, providers will be required to obtain preauthorization through Blue Cross and Blue Shield of New Mexico (BCBSNM), Optum, or eviCore for certain procedures for Blue Cross Medicare Advantage members as noted in the MAPD Benefit Preauthorization Procedure Code List, Effective 1/1/2020, below. For members NOT attributed to Optum, preauthorization should be obtained from BCBSNM unless the applicable entry in the MAPD Benefit Preauthorization Procedure Code List references eviCore. For members attributed to Optum, preauthorization should be obtained from Optum, even if the applicable entry in the MAPD Benefit Preauthorization Procedure Code List references eviCore. Any entry that references eviCore should be preauthorized through eviCore except for members attributed to Optum. The member's ID Card will indicate that the member is attributed to Optum. Services performed without benefit preauthorization may be denied for payment in whole or in part, and you may not seek reimbursement from members. Member eligibility and benefits should be checked prior to every scheduled appointment. Eligibility and benefit quotes include membership status, coverage status and other important information, such as applicable copayment, coinsurance and deductible amounts. It is strongly recommended that providers ask to see the member's ID card for current information and a photo ID to guard against medical identity theft. A referral to an out-of-plan or out-of-network provider which is necessary due to network inadequacy or continuity of care must be reviewed by the BCBSNM Utilization Management or DMG (if the member is attributed to DMG this information will be reflected on the ID card) prior to a BCBSNM patient receiving care. -

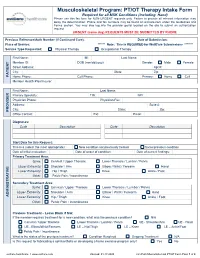

PT/OT Therapy Intake Form Required for All MSK Conditions (Including Hand) Please Use This Fax Form for NON-URGENT Requests Only

Musculoskeletal Program: PT/OT Therapy Intake Form Required for all MSK Conditions (Including Hand) Please use this fax form for NON-URGENT requests only. Failure to provide all relevant information may delay the determination. Phone and fax numbers may be found on eviCore.com under the Guidelines and Forms section. You may also log into the provider portal located on the site to submit an authorization request. URGENT (same day) REQUESTS MUST BE SUBMITTED BY PHONE Previous Reference/Auth Number (If Continued Care): Date of Submission: Place of Service: ****** Note: This is REQUIRED for WellCare Submissions ******* Service Type Requested: Physical Therapy Occupational Therapy First Name: MI: Last Name: Member ID: DOB (mm/dd/yyyy): Gender: Male Female Street Address: Apt #: City: State: Zip: PATIENT Home Phone: Cell Phone: Primary: Home Cell Member Health Plan/Insurer: First Name: Last Name: Primary Specialty: TIN: NPI: Physician Phone: Physician Fax: Address: Suite #: City: State: Zip: PROVIDER Office Contact: Ext: Email: Diagnoses: Code Description Code Description Start Date for this Request: This is a (select the most appropriate): New condition not previously treated Same/previous condition Date of initial evaluation: Date of onset of condition: Date of current findings: Primary Treatment Area: Spine: Cervical / Upper Thoracic Lower Thoracic / Lumbar / Pelvis Upper Extremity: Shoulder / Arm Elbow / Wrist / Forearm Hand Lower Extremity: Hip / Thigh Knee Ankle / Foot Other: Pelvic Pain / Incontinence Secondary Treatment Area: Spine: -

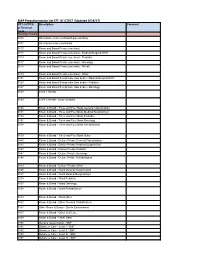

MAP Preauthorization List EFF: 8/1/2017 (Updated 8/24/17)

MAP Preauthorization List EFF: 8/1/2017 (Updated 8/24/17) CPT, HCPCS Description Comment or Revenue Code Revenue Codes 0100 All inclusive room and board plus ancillary 0101 All inclusive room and board 0110 Room and Board Private (one bed) 0111 Room and Board Private (one bed) - Medical/Surgical/GYN 0113 Room and Board Private (one bed) - Pediatric 0117 Room and Board Private (one bed) - Oncology 0118 Room and Board Private (one bed) - Rehab 0119 Room and Board Private (one bed) - Other 0121 Room and Board Semiprivate (two beds) - Medical/Surgical/GYN 0123 Room and Board Semiprivate (two beds) - Pediatric 0127 Room and Board Semiprivate (two beds) - Oncology 0128 Level 1 Rehab 0129 Level 2 Rehab - acute complex 0130 Room & Board - Three and Four Beds General Classification 0131 Room & Board - Three and Four Beds Medical/Surgical/Gyn 0133 Room & Board - Three and Four Beds Pediatric 0137 Room & Board - Three and Four Beds Oncology 0138 Room & Board - Three and Four Beds Rehabilitation 0139 Room & Board - Three and Four Beds Other 0140 Room & Board - Deluxe Private General Classification 0141 Room & Board - Deluxe Private Medical/Surgical/Gyn 0143 Room & Board - Deluxe Private Pediatric 0147 Room & Board - Deluxe Private Oncology 0148 Room & Board - Deluxe Private Rehabilitation 0149 Room & Board - Deluxe Private Other 0150 Room & Board - Ward General Classification 0151 Room & Board - Ward Medical/Surgical/Gyn 0153 Room & Board - Ward Pediatric 0157 Room & Board - Ward Oncology 0158 Room & Board - Ward Rehabilitation 0159 Room & Board - -

114.3 Cmr: Division of Health Care Finance and Policy Ambulatory Care

114.3 CMR: DIVISION OF HEALTH CARE FINANCE AND POLICY AMBULATORY CARE 114.3 CMR 40.00: RATES FOR SERVICES UNDER M.G.L. c. 152, WORKERS’ COMPENSATION ACT Section 40.01: General Provisions 40.02: General Definitions 40.03: Service and Rate Coverage Provisions 40.04: Provisions Affecting Eligible Providers 40.05: Policies for Individual Service Types 40.06: Fees 40.07: Appendices 40.08: Severability 40.01: General Provisions (1) Scope, Purpose and Effective Date. 114.3 CMR 40.00 governs the payment rates effective April 1, 2009 for purchasers of health care services under M.G.L. c. 152, the Workers’ Compensation Act. Payment rates for services provided by hospitals are set forth in 114.1 CMR 41.00. Program policies relating to medical necessity and clinical appropriateness are determined pursuant to M.G.L. c. 152 and 452 CMR 6.00. (2) Coverage. The payment rates set forth in 114.3 CMR 40.06 are full payment for services provided under M.G.L. c. 152, § 13, including any related administrative or overhead costs. The insurer, employer and health care service provider may agree upon a different payment rate for any service set forth in the fee schedule in 114.3 CMR 40.00. No employee may be held liable for the payment for health care services determined compensable under M.G.L. c. 152, § 13. (3) Administrative Bulletins. The Division may issue administrative bulletins to clarify substantive provisions of 114.3 CMR 40.00, or to publish procedure code updates and corrections. For coding updates and correction, the bulletin will list: (a) new code numbers for existing codes, with the corresponding cross references between existing and new codes numbers; (b) deleted codes for which there are no corresponding new codes; and (c) codes for entirely new services that require pricing. -

Artificial Finger Joint Replacement Due to a Giant Cell Tumor of the Tendon Sheath with Bone Destruction: a Case Report

3502 ONCOLOGY LETTERS 10: 3502-3504, 2015 Artificial finger joint replacement due to a giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath with bone destruction: A case report HUI LU, HUI SHEN, QIANG CHEN, XIANG-QIAN SHEN and SHOU-CHENG WU Department of Hand Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310003, P.R. China Received October 24, 2014; Accepted September 25, 2015 DOI: 10.3892/ol.2015.3813 Abstract. The current study presents the case of a 25-year-old excised completely and the function of the joints was recov- male who developed tumor recurrence of the proximal ered. phalange of the ring finger on the right hand 4 years after partial tumor resection surgery. An X-ray of the right hand Case report showed that the distal bone of the proximal phalange on the ring finger was destroyed. An artificial finger joint replace- A 25-year-old male was admitted to The First Affiliated ment was performed using a silicone joint for this unusual Hospital, College of Meicine, ZheJiang University (Hangzhou, tumor recurrence. The pathological findings were indicative of Zhejiang, China) with tumor recurrence of the proximal a giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath. As a result of surgery, phalange of the ring finger on the right hand 4 years after the patient's proximal interphalangeal point motion recovered partial tumor resection surgery. The patient had no history to the pre-operative level. The pre-operative and post-operative of trauma or infection and was previously healthy. A physical disabilities of the arm, at shoulder and hand and total activity examination revealed swelling of the proximal phalange of the measurement values were 1.67 and 3.33, and 255 and 243˚, finger without clear cause, multiple nodules in the local areas respectively. -

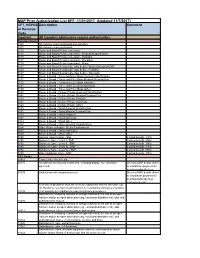

MAP Prior Authorization List EFF: 11/01/2017 (Updated 11/7/2017)

MAP Prior Authorization List EFF: 11/01/2017 (Updated 11/7/2017) CPT, HCPCS Description Comment or Revenue Code Inpatient All Inpatient admissions require authorization Revenue Codes 0100 All inclusive room and board plus ancillary 0101 All inclusive room and board 0110 Room and Board Private (one bed) 0111 Room and Board Private (one bed) - Medical/Surgical/GYN 0113 Room and Board Private (one bed) - Pediatric 0117 Room and Board Private (one bed) - Oncology 0119 Room and Board Private (one bed) - Other 0121 Room and Board Semiprivate (two beds) - Medical/Surgical/GYN 0123 Room and Board Semiprivate (two beds) - Pediatric 0127 Room and Board Semiprivate (two beds) - Oncology 0130 Room & Board - Three and Four Beds General Classification 0131 Room & Board - Three and Four Beds Medical/Surgical/Gyn 0133 Room & Board - Three and Four Beds Pediatric 0137 Room & Board - Three and Four Beds Oncology 0139 Room & Board - Three and Four Beds Other 0140 Room & Board - Deluxe Private General Classification 0141 Room & Board - Deluxe Private Medical/Surgical/Gyn 0143 Room & Board - Deluxe Private Pediatric 0147 Room & Board - Deluxe Private Oncology 0149 Room & Board - Deluxe Private Other 0150 Room & Board - Ward General Classification 0151 Room & Board - Ward Medical/Surgical/Gyn 0153 Room & Board - Ward Pediatric 0157 Room & Board - Ward Oncology 0159 Room & Board - Ward Other 0160 Room & Board - Other General Classification 0164 Other Room & Board - Sterile Environment 0167 Room & Board - Other Self Care 0169 Room & Board - Other Other 0190 General -

184591/2021/Estt-Ne Hr

168 184591/2021/ESTT-NE_HR PUSHPAWATI SINGHANIA HOSPITAL & RESEARCH INSTITUTE A MULTISPECIALITY HOSPITAL (formally known as Puspawati Singhania Research Institute for liver,Renal & Digestive Diseases) (w.e.f. 01.04.2020) OPD CHARGES FEES (Rs) SR. NO. CONSULTANT NAME FIRST SUBS. GASTROENTEROLOGY 1PROF.(DR). R.K.TANDON 20001500 2LT. COL. (DR) ARUN KUMAR 12001200 3DR. DINESH SINGHAL 10001000 4DR. MANOJ KUMAR 10001000 5DR. NRIPEN SAIKIA 10001000 6DR. RAJIV BAIJAL 10001000 7DR. RAHUL GUPTA 20002000 8DR. SHUBHAM VATSYA 900900 SURGICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY & LIVER TRANSPLANT 1DR. K.R VASUDEVAN 12001200 2DR. MANOJ GUPTA 10001000 3DR. BHUSHAN P. BHOLA 12001200 NEPHROLOGY 1DR. SANJEEV SAXENA 12001200 2DR. RAVI BANSAL 10001000 3DR. RAJESH GOEL 800800 UROLOGY 1DR. P.P.SINGH 12001200 2DR. JAGDEEP BALYAN 11001100 3DR. A.S.MALHOTRA 11001100 CARDIOLOGIST 1DR. T.S.KLER 10001000 2DR. VINAYAK AGRAWAL 12001200 3DR. AVINASH VERMA 10001000 4DR. S. N. PATHAK 10001000 5DR. ABHINAV AGGARWAL 10001000 CARDIO SURGERY 1DR. BALRAM AIRAN 10001000 2DR. VIJAY MOHAN KOHLI 12501250 3DR GAURAV GUPTA 10001000 NEUROLOGOY 1DR. SHAMSHER DWIVEDEE 20001800 NEURO SURGERY 1DR. SUMIT GOYAL 10001000 ENDOCRINOLOGY 1DR. MONIKA SHARMA 1001000 PULMONOLOGY 1DR. G.C. KHILNANI 15001500 2DR. NEETU JAIN 10001000 G.I SURGERY 1DR. SANJAY CHAUREY 15001500 2DR. RAJEEV KHANNA 12001000 3DR. HARISH KAPILA 15001500 ONCOLOGY (SURGERY) 1DR. ARVIND KUMAR 15001500 2DR. SALEEM NAYAK 15001500 3DR. VIVEK GUPTA 15001500 4DR. VIKRANT SHARMA 15001500 ONCOLOGY 1DR. AMISH VORA 15001500 2DR. AMIT UPADHYAY 15001500 ORTHOPEDICS 1DR. P.P. KOTWAL 15001500 2DR. GAURAV PRAKASH BHARDWAJ 12001200 Page 1 169 184591/2021/ESTT-NE_HR 3DR. U.K.SADHOO 12001200 4DR. G.S.TUCKER 12001200 5DR. ANIL MISHRA 10001000 6DR. -

Sentinel Report Cder Mpl1r Wp155

Disclaimer The following report(s) provides findings from an FDA‐initiated query using Sentinel. While Sentinel queries may be undertaken to assess potential medical product safety risks, they may also be initiated for various other reasons. Some examples include determining a rate or count of an identified health outcome of interest, examining medical product use, exploring the feasibility of future, more detailed analyses within Sentinel, and seeking to better understand Sentinel capabilities. Data obtained through Sentinel are intended to complement other types of evidence such as preclinical studies, clinical trials, postmarket studies, and adverse event reports, all of which are used by FDA to inform regulatory decisions regarding medical product safety. The information contained in this report is provided as part of FDA’s commitment to place knowledge acquired from Sentinel in the public domain as soon as possible. Any public health actions taken by FDA regarding products involved in Sentinel queries will continue to be communicated through existing channels. FDA wants to emphasize that the fact that FDA has initiated a query involving a medical product and is reporting findings related to that query does not mean that FDA is suggesting health care practitioners should change their prescribing practices for the medical product or that patients taking the medical product should stop using it. Patients who have questions about the use of an identified medical product should contact their health care practitioners. The following report contains a description of the request, request specifications, and results from the modular program run(s). If you are using a web page screen reader and are unable to access this document, please contact the Sentinel Operations Center for assistance at [email protected]. -

Hand Rehabilitation Current Awareness Newsletter

1 Hand Rehabilitation Current Awareness Newsletter JANUARY 2016 2 Your Local Librarian Whatever your information needs, the library is here to help. As your outreach librarian I offer literature searching services as well as training and guidance in searching the evidence and critical appraisal – just email me at library @uhbristol.nhs.uk OUTREACH: Your Outreach Librarian can help facilitate evidence-based practise for all in the Orthogeriatrics team, as well as assisting with academic study and research. We can help with literature searching, obtaining journal articles and books, and setting up individual current awareness alerts. We also offer one-to-one or small group training in literature searching, accessing electronic journals, and critical appraisal. Get in touch: [email protected] LITERATURE SEARCHING: We provide a literature searching service for any library member. For those embarking on their own research it is advisable to book some time with one of the librarians for a 1 to 1 session where we can guide you through the process of creating a well-focused literature research and introduce you to the health databases access via NHS Evidence. Please email requests to [email protected] 3 Contents New from Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews ........................................................................... 4 Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. 4 New Activity in Up-to-Date .................................................................................................................... -

American Association for Hand Surgery | 2015 Annual Meeting 1

Oral Presentation Abstracts 1. Side-to-side vs. Pulvertaft Extensor Tendon Repair; Biomechanical Study Michael Rivlin, Amir Reza Kachooei, MD, Ali Hosseini, PhD, Kyle Eberlin, MD, Nikola Zivaljevic, MD, Guoan Li, PhD and Chaitanya S. Mudgal, MD Department of Orthopaedics, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard University, Boston, MA Introduction: Extensor tendons can be coapted using a weave suture technique to provide tensile strength and repair surface overlap. Pulvertaft (PT) weave is the standard method of extensor tendon repair. However, recently, Brown and colleagues described a side-to-side (STS) tendon repair technique (one weave). This method may compare in speed of repair, while simpler, potentially less bulky and without the need specialized equipment while not compromising repair strengths and tensile properties. We hypothesize that STS is more practical than PT with matching biomechanical characteristics. Materials and Methods: In a biomechanical study on 6 cadaver arms, we harvested 30 extensor tendons including four extensor digitorum communis (EDC) and one extensor indicis proprius (EIP). Three hand surgical fellows with similar backgrounds of training under the same conditions and precise standardized technique performed timed repairs (5 PT and 5 STS per surgeon). Following the repairs, the tendons were passed through a custom made graft sizing guide to determine bulk and the results were expressed as a repaired vs. native diameter ratio. The specimens were then tested for ultimate strength and fatigue properties (Instron Inc., Norwood, MA). Failure type and mechanical properties were recorded and compared to the native tendon portion. Results: The STS technique demonstrated comparable time to repair (average tendon repair STS: 8.16 min vs. -

Surgical Services Referral Guide St

St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center Surgical Services Referral Guide St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center surgical services are available for elective and emergent procedures from many of Boston’s finest board-certified surgeons who work collaboratively with our highly trained anesthesiologists, nurses, technicians, therapists and aides. Together they provide a comprehensive surgical experience from pre-admission education and preparation through to discharge and follow-up care. St. Elizabeth’s surgeons utilize modern, new ORs and leading-edge technologies, including robotic-assisted surgical techniques. There is a state-of-the-art intensive care unit, among the newest in the region with 24/7 eICU support and dedicated step-down care in a new, all private-bed Cardiac Surgery Unit with a dedicated multidisciplinary cardiovascular care team. St. Elizabeth’s has received numerous quality awards and accreditations for its surgical services, including: • One of Healthgrades America’s 50 Best Hospitals for Cardiac Surgery™ for 4 Years in a Row (2018-2021) • The only hospital in Boston named a Five-Star Recipient for Hip Fracture Treatment in 2021 • Named a TransCarotid Artery Revascularization (TCAR) Center of Excellence by Silk Road Medical, Inc., 2019 • Named by U.S. News World Report a High Performing Hospital in treating heart failure and performing heart bypass in its annual U.S. News’ 2018-2019 High Performing Hospital listing • Earned Center of Excellence accreditation through the American College of Surgeons Metabolic and Bariatric • Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP®) for the Steward Center for Weight Control at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center • Physicians consistently ranked in U.S. -

Illinois Medicaid Benefit Preauthorization Procedure Code

Illinois Medicaid Benefit Preauthorization Procedure Code List, Effective 1/1/2021 (Updated 7/1/21) This list includes Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) and/or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes related to services/categories for which benefit preauthorization may be required. This list is not exhaustive. The presence of codes on this list does not necessarily indicate coverage under the member benefits contract. Always check eligibility and benefits first, prior to rendering services. Member contracts differ in their benefits. Consult the member benefit Utilization Management Process booklet, or contact a customer service representative to determine coverage for a specific medical service or supply. Note: Green highlighted codes are managed by eviCore healthcare (eviCore). Orange highlighted codes are managed by eviCore for Blue Cross Community Health Plans℠ (BCCHP℠) members and by Prime Therapeutics for Blue Cross Community MMAI (Medicare-Medicaid)℠ members. CPT and HCPCS Codes That May Description of Procedure Code Medical Records Request Information Required Require Prior Authorization 11920 CORRECT SKIN COLOR 6.0 CM/< Pre-operative evaluation, history and physical including functional impairment, and operative report. 01990 SUPPORT FOR ORGAN DONOR Recent history and physical, plan of care, and documentation of medical necessity. 11921 CORRECT SKN COLOR 6.1-20.0CM Pre-operative evaluation, history and physical including functional impairment, and operative report. 11922 CORRECT SKIN COLOR EA 20.0CM Pre-operative evaluation, history and physical including functional impairment, and operative report. 11950 TX CONTOUR DEFECTS 1 CC/< Pre-operative evaluation, history and physical including functional impairment, and operative report. 11951 TX CONTOUR DEFECTS 1.1-5.0CC Pre-operative evaluation, history and physical including functional impairment, and operative report.