2004-6 Layout.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

+P+-+K+- +-+-+-+- B -+-+P+-+ W -+-+-+-+ Zlw-+P+R +-+-+-Z- P+-+N+Q+ P+-+-+-+ +-+-+-+- Z-+K+-+- -+-+-TP+ Kwqs-Z-S +-+-+RM- +-+-+-+

Contents Symbols 4 Introduction 5 Part 1: The Basics 1 Pin 7 2 Deflection 16 3 Overload 23 4 Decoy 28 5 Double Attack 36 6 Knight Fork 44 7 Discovered Attack 50 8 Clearance 56 9 Obstruction 64 10 Removing the Defender 71 11 The Power of the Pawn 77 12 Back-Rank Mate 85 13 Stalemate 91 14 Perpetual Check and Fortresses 96 Part 2: Advanced Tactics 15 f7: Weak by Presumption 103 16 The Vulnerable Rook’s Pawn 111 17 Attacking the Fianchetto 118 18 The Mystery of the Opposite-Coloured Bishops 125 19 Chess Highways: Open Files 131 20 Trapping a Piece 141 21 Practice Makes Perfect 149 Solutions 158 Index of Players 188 Index of Composers 191 KNIGHT FORK 6 Knight Fork The knight is considered to be the least powerful White is now a queen and two rooks down – piece in chess (besides the pawn, of course). As a deficit of approximately 19 ‘pawns’. His only the great world champion Jose Raul Capablanca remaining piece is a knight. But a brave one... taught us, the other minor piece, the bishop, is 3 Ìe3+ Êf6 4 Ìxd5+ Êf5 5 Ìxe7+ Êf6 6 better in 90% of cases. However, due to its spe- Ìxg8+ (D) cific qualities the knight is a tremendously dan- gerous piece. It is nimble and its jumps can be -+-+-+N+ quite shocking. That is why a double attack by a +-+-+p+- knight is usually distinguished from other dou- B ble attacks and called a fork. -+-+nm-M +-+-z-+- A single knight may cause incredible dam- age in the right circumstances: -+-+-+-+ +-+-+PZ- -+-+-+q+ -+-+-+-+ +-+r+p+- +-+-+-+- W -+N+nm-M +-+rz-+- The knight has managed to remove most of Black’s army. -

248 Cmr: Board of State Examiners of Plumbers and Gas Fitters

248 CMR: BOARD OF STATE EXAMINERS OF PLUMBERS AND GAS FITTERS 248 CMR 10.00: UNIFORM STATE PLUMBING CODE Section 10.01: Scope and Jurisdiction 10.02: Basic Principles 10.03: Definitions 10.04: Testing and Safety 10.05: General Regulations 10.06: Materials 10.07: Joints and Connections 10.08: Traps and Cleanouts 10.09: Interceptors, Separators, and Holding Tanks 10.10: Plumbing Fixtures 10.11: Hangers and Supports 10.12: Indirect Waste Piping 10.13: Piping and Treatment of Special Hazardous Wastes 10.14: Water Supply and the Water Distribution System 10.15: Sanitary Drainage System 10.16: Vents and Venting 10.17: Storm Drains 10.18: Hospital Fixtures 10.19: Plumbing in Manufactured Homes and Construction Trailers 10.20: Public and Semi-public Swimming Pools 10.21: Boiler Blow-off Tank 10.22: Figures 10.23: Vacuum Drainage Systems 10.01: Scope and Jurisdiction (1) Scope. 248 CMR 10.00 governs the requirements for the installation, alteration, removal, replacement, repair, or construction of all plumbing. (2) Jurisdiction. (a) Nothing in 248 CMR 10.00 shall be construed as applying to: 1. refrigeration; 2. heating; 3. cooling; 4. ventilation or fire sprinkler systems beyond the point where a direct connection is made with the potable water distribution system. (b) Sanitary drains, storm water drains, hazardous waste drainage systems, dedicated systems, potable and non-potable water supply lines and other connections shall be subject to 248 CMR 10.00. 10.02: Basic Principles Founding of Principles. 248 CMR 10.00 is founded upon basic principles which hold that public health, environmental sanitation, and safety can only be achieved through properly designed, acceptably installed, and adequately maintained plumbing systems. -

Little Chess Evaluation Compendium by Lyudmil Tsvetkov, Sofia, Bulgaria

Little Chess Evaluation Compendium By Lyudmil Tsvetkov, Sofia, Bulgaria Version from 2012, an update to an original version first released in 2010 The purpose will be to give a fairly precise evaluation for all the most important terms. Some authors might find some interesting ideas. For abbreviations, p will mean pawns, cp – centipawns, if the number is not indicated it will be centipawns, mps - millipawns; b – bishop, n – knight, k- king, q – queen and r –rook. Also b will mean black and w – white. We will assume that the bishop value is 3ps, knight value – 3ps, rook value – 4.5 ps and queen value – 9ps. In brackets I will be giving purely speculative numbers for possible Elo increase if a specific function is implemented (only for the functions that might not be generally implemented). The exposition will be split in 3 parts, reflecting that opening, middlegame and endgame are very different from one another. The essence of chess in two words Chess is a game of capturing. This is the single most important thing worth considering. But in order to be able to capture well, you should consider a variety of other specific rules. The more rules you consider, the better you will be able to capture. If you consider 10 rules, you will be able to capture. If you consider 100 rules, you will be able to capture in a sufficiently good way. If you consider 1000 rules, you will be able to capture in an excellent way. The philosophy of chess Chess is a game of correlation, and not a game of fixed values. -

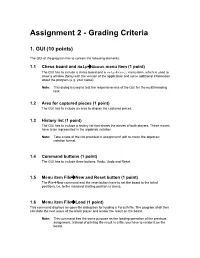

Assignment2 Grading Criteria

Assignment 2 - Grading Criteria 1. GUI (10 points) The GUI of the program has to contain the following elements: 1.1 Chess board and HelpÆAbout menu item (1 point) The GUI has to include a chess board and a HelpÆAbout menu item, which is used to show a window (form) with the version of the application and some additional information about the program (e.g. your name). Note: This dialog is used to test the responsiveness of the GUI for the multithreading task. 1.2 Area for captured pieces (1 point) The GUI has to include an area to display the captured pieces. 1.3 History list (1 point) The GUI has to include a history list that shows the moves of both players. These moves have to be represented in the algebraic notation. Note: Take a look at the link provided in assignment1.pdf to check the algebraic notation format. 1.4 Command buttons (1 point) The GUI has to include three buttons: Redo, Undo and Reset. 1.5 Menu item FileÆNew and Reset button (1 point) The FileÆNew command and the reset button have to set the board to the initial positions. I.e. to the standard starting position in chess. 1.6 Menu item FileÆLoad (1 point) This command displays an open-file dialog box for loading a Forsyth file. The program shall then calculate the next move of the black player and render the result on the board. Note: This command has the same purpose as the loading operation of the previous assignment. Instead of printing the result in a file, you have to render it on the board. -

PAUL MORPHY Drawn

PRICE FIVE CENTS: : VOLUME 301. CEDAB EAPIDS,JOWA, SATURDAY, DECEMBER 29, 1900-12 PAGES-PAGES 9 TO 12. 1 -creditors can force their debtor' into. •3 SSI, and admittedly the .-best player to Paris and remained about eighteen ver chessmen was taken by Walter Denegre, acting for . tho Manhattan, •the court andi have an equal'settle- 'In Europe. Tn'-addition to the match months. , ' ~~- 1 ment for their accounts per ratio. games, Morphy and Anderssen played Durhig- the ten years following his Chess club of New York, price $.l.r,50: BANKRUPTCY and the silver -wreath .sold for $250, This is the involuntary act and it-;li THE LIFE OF six informal games, of which the return from Europe .in .ISM Morphy's considered by lawyers and- judges a* also bouffht by Mr. Samory. : Prussian master scored only one. The practice ot chess was limited to cas- 1 a whole just and equitable. • informal and match fiumes made a ual.games with intimate friends, chief- An engaging pastime oil chess wrlt- : sra and critics of. late years has:.been "Now comes that -portion, which B total of seventeen games played hy •ly with Charles A. -Murlan ot New COURT BUSY so generally abused, the sectlon"of that o" comparing the laf.ter-day mas- these masters, of which Morphy won Orleans and Arnons .de Riviere of which so many take advantage^-to- twelve, Anderssen throe, and two-were Paris, It Is thought,tiie total number ters with Morphy, but so far" the most flatteri-ng; comparisons have nev- ward- off the host or honest-creditors; PAUL MORPHY drawn. -

Checkers for the Three-Move Expert

Checkers for the QRRRRRRRRS TEA1EA2EA3EA4U TA5EA6EA7EA8EU TE 9EA!0E !1EA!2U T !3E !4E !5E !6EU TEB!7EA!8E !9E @0U TB@1E @2E @3EB@4EU TEB@5EB@6EB@7EB@8U TB@9EB#0EB#1EB#2EU VWWWWWWWWX 3-Move Expert (Balanced Ballots) By Richard Pask 1 © Richard Pask 2020 2 Checkers for the 3-Move Expert (Balanced Ballots) Logical Checkers Book 4 By Richard Pask 3 Table of Contents Introduction to Logical Checkers Book 4 7 Endgame Chapter 22: Man-Down Endgames 10 Lesson 206: Fourth Position (Black man on 21) Lesson 207: Payne’s Single-Corner Draw (Black man on 13) Lesson 208: Third Position (Black man on 5) Lesson 209: Barker’s Triangle (Black man on 5) Lesson 210: Strickland’s Position (Black man on 5) Lesson 211: Payne’s Double-Corner Draw (Black man on 28) Lesson 212: Roger’s Draw (Black man on 20) Lesson 213: Howard’s Draw (Black man on 12) Lesson 214: Holding on the Left or the Right? Lesson 215: McCulloch’s Draw (Black men on 5 and 12, White man on 20) Lesson 216: Miller’s Draw (Black men on 4 and 5, White man on 13) Lesson 217: Dr Brown’s Draw (Black men on 5 and 13) Lesson 218: Sinclair’s Draw (Black men on 4 and 12) Chapter 23: Endgame Themes 43 Lesson 219: Self-Imposed 2 for 1 Lesson 220: Flotation Lesson 221: Single-Corner Grip Lesson 222: Major Grip Lesson 223: The Sentinel Lesson 224: Masked Steal Lesson 225: The Push-Away Lesson 226: The Square of Exchange Lesson 227: Perpetual Check Lesson 228: Masked 2 for 1 Lesson 229: Threat and execution Lesson 230: Double-Corner grip 4 Midgame Chapter 24: Midgame Themes 90 Lesson 231: The Outpost Man -

Louisiana French Creole Poet, Essayist, and Composer Donna M

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Leona Queyrouze (1861-1938): Louisiana French Creole poet, essayist, and composer Donna M. Meletio Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Meletio, Donna M., "Leona Queyrouze (1861-1938): Louisiana French Creole poet, essayist, and composer" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2146. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2146 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LEONA QUEYROUZE (1861-1938) LOUISIANA FRENCH CREOLE POET, ESSAYIST, AND COMPOSER A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English by Donna M. Meletio B.A., University of Texas San Antonio, 1990 M.A., University of Texas San Antonio, 1994 August, 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Donna M. Meletio All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For their support throughout this project and for their patience and love, I would like to thank my daughters, Sarah, Maegan, and Kate, who are the breath and heart of my life. I would also like to thank the strong and beautiful women and men who have walked through this life journey with me: my life-long friend Dr. -

Play Chess with Paul Morphy

The Historic New Orleans Collection presents Play Chess with Paul Morphy Lesson 1, History Daguerreotype of Paul Morphy framed in an embossed case, between 1857 and 1859 (THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Boyd Cruise Fund, 1996.75) In the winter of 1857, 20- year-old Paul Morphy had just returned home to New Orleans after defeating the best chess players in the country at the first American Chess Congress, held in New York City. Announcement in the New-York Tribune, November 7, 1857 Members of the first American Chess Congress, 1857 (courtesy of Cornell University Library) Because of Morphy’s accomplishment, a chess craze swept New Orleans. Soon after Morphy’s victory, the New Orleans Chess Club elected him as president. The meetings were held at the Mercantile Library Association, located on Exchange Alley. At these events, Morphy entertained crowds with extraordinary feats on the chessboard. New Orleans Chess Club announcement in the Times-Picayune, January 13, 1858 Lithograph illustration of Exchange Alley, ca. 1870, by Marie Adrien Persac. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1950.39) Modern chess developed in the Mediterranean during the 15th century, as part of the Italian Renaissance. Around this same time, Europeans began to voyage to Africa and the Americas. Spanish, Portuguese, French, and English ships spread the game of chess—along with plants, technology, and disease—throughout the New World. Taking Possession Of Louisiana And The River Sauvage matachez en guerrier, 1735, by Alexandre Mississipi . ., ca. 1860, by Jean-Adolphe Bocquin De Batz (courtesy of Peabody Museum of Archaeology (THNOC, 1970.1) and Ethnology, Harvard University) In New Orleans, the game grew in popularity as francophone émigrés poured into the city following the French and Haitian Revolutions at the turn of the 19th century. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Chapter 10, Different Objectives of Play

Chapter 10 Different objectives of play [The normal objective of a game of chess is to give checkmate. Some of the games which can be played with chessmen have quite different objectives, and two of them, Extinction Chess and Losing Chess, have proved to be among the most popular of all chess variants.] 10.1 Capturing or baring the king Capturing the king. The Chess Monthly than about the snobbery of Mr Donisthorpe!] hosted a lively debate (1893-4) on the suggestion of a Mr Wordsworth Donisthorpe, Baring the king. The rules of the old chess whose very name seems to carry authority, allowed a (lesser) win by ‘bare king’ and that check and checkmate, and hence stalemate, and Réti and Bronstein have stalemate, should be abolished, the game favoured its reintroduction. [I haven’t traced ending with the capture of the king. The the Bronstein reference, but Réti’s will be purpose of this proposed reform was to reduce found on page 178 of the English edition of the number of draws then (as now) prevalent Modern Ideas in Chess. It is in fact explicit in master play. Donisthorpe claimed that both only in respect of stalemate, though the words Blackburne and the American master James ‘the original rules’ within it can be read as Mason were in favour of the change, adding supporting bare king as well, and perhaps ‘I have little doubt the reform would obtain I ought to quote it in full. After expounding the support of both Universities’ which says the ancient rules, he continues: ‘Those were something about the standing of Oxford and romantic times for chess. -

Colorado Chess Informant

Colorado Chess Informant YOUR COLORADOwww.colorado-chess.com STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION’S Apr 2004 Volume 31 Number 2 ⇒ On the web: http://www.colorado-chess.com Volume 31 Number 2 Apr 2004/$3.00 COLORADO CHESS Inside This Issue INFORMANT INFORMANT Cross tables and reports: pg(s) Winter Springs Open 4-5 DCC Martin Luther King 9 DCC Club Championship 11 Oscars for Chess on the Big Screen Foundation Cup Team 22-23 Loveland Open 28-29 Can you identify the movies that each of these chess positions is from? Games How tactical can 1.Nf3 be 6-7 Readers Games 16 Game of the Month 25 Departments CSCA Info./Editor’s Square 2 CSCA Sense 3 Club Directory 24 Tournament announcements 30-32 1. Oscar for: Last checkmate 2. Oscar for: Most violent 3. Oscar for: Best romantic on Earth, before it was piece captures chess movie Features conquered by aliens Another Good Man Gone 4 Chess Truisms for Class Players 8 The Kosher Patzer 8 Chess Etiquette 101 13 Tactics Time 15 Oscars for Chess 17-20 The Frugal Chess Player 14 Operation Swindle Master 21 CO Players on USCF Top 100s 27 4. Oscar for: Best portrayal 5. Oscar for: Most beautiful 6. Oscar for: Best chess of chess bums gambling in a setting for a chess game in a game ever played on a trip park spy movie to Jupiter Page 1 Answers page 2 and related article on page 17 Colorado Chess Informant www.colorado-chess.com Apr 2004 Volume 31 Number 2 COLORADO STATE The Editor’s Square CHESS ASSOCIATION Junior Representative: Joshua Suresh CO Chess Informant The COLORADO STATE (303) 400-0595 Editor Tim Brennan CHESS ASSOCIATION, INC, [email protected] is a Sec. -

Chess Pieces – Left to Right: King, Rook, Queen, Pawn, Knight and Bishop

CCHHEESSSS by Wikibooks contributors From Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License". Image licenses are listed in the section entitled "Image Credits." Principal authors: WarrenWilkinson (C) · Dysprosia (C) · Darvian (C) · Tm chk (C) · Bill Alexander (C) Cover: Chess pieces – left to right: king, rook, queen, pawn, knight and bishop. Photo taken by Alan Light. The current version of this Wikibook may be found at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Chess Contents Chapter 01: Playing the Game..............................................................................................................4 Chapter 02: Notating the Game..........................................................................................................14 Chapter 03: Tactics.............................................................................................................................19 Chapter 04: Strategy........................................................................................................................... 26 Chapter 05: Basic Openings............................................................................................................... 36 Chapter 06: