Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement, Tehachapi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robinson V. Salazar 3Rd Amended Complaint

Case 1:09-cv-01977-BAM Document 211 Filed 03/19/12 Page 1 of 125 1 Evan W. Granowitz (Cal. Bar No. 234031) WOLF GROUP L.A. 2 11400 W Olympic Blvd., Suite 200 Los Angeles, California 90064 3 Telephone: (310) 460-3528 Facsimile: (310) 457-9087 4 Email: [email protected] 5 David R. Mugridge (Cal. Bar No. 123389) 6 LAW OFFICES OF DAVID R. MUGRIDGE 2100 Tulare St., Suite 505 7 Fresno, California 93721-2111 Telephone: (559) 264-2688 8 Facsimile: (559) 264-2683 9 Attorneys for Plaintiffs Kawaiisu Tribe of Tejon and David Laughing Horse Robinson 10 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 11 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 12 13 KAWAIISU TRIBE OF TEJON, and Case No.: 1:09-cv-01977 BAM DAVID LAUGHING HORSE ROBINSON, an 14 individual and Chairman, Kawaiisu Tribe of PLAINTIFFS’ THIRD AMENDED 15 Tejon, COMPLAINT FOR: 16 Plaintiffs, (1) UNLAWFUL POSSESSION, etc. 17 vs. (2) EQUITABLE 18 KEN SALAZAR, in his official capacity as ENFORCEMENT OF TREATY 19 Secretary of the United States Department of the Interior; TEJON RANCH CORPORATION, a (3) VIOLATION OF NAGPRA; 20 Delaware corporation; TEJON MOUNTAIN VILLAGE, LLC, a Delaware company; COUNTY (4) DEPRIVATION OF PROPERTY 21 OF KERN, CALIFORNIA; TEJON IN VIOLATION OF THE 5th RANCHCORP, a California corporation, and AMENDMENT; 22 DOES 2 through 100, inclusive, (5) BREACH OF FIDUCIARY 23 Defendants. DUTY; 24 (6) NON-STATUTORY REVIEW; and 25 (7) DENIAL OF EQUAL 26 PROTECTION IN VIOLATION OF THE 5th AMENDMENT. 27 DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL 28 1 PLAINTIFFS’ THIRD AMENDED COMPLAINT Case 1:09-cv-01977-BAM Document 211 Filed 03/19/12 Page 2 of 125 1 Plaintiffs KAWAIISU TRIBE OF TEJON and DAVID LAUGHING HORSE ROBINSON 2 allege as follows: 3 I. -

Center Comments to the California Department of Fish and Game

July 24, 2006 Ryan Broderick, Director California Department of Fish and Game 1416 Ninth Street, 12th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 RE: Improving efficiency of California’s fish hatchery system Dear Director Broderick: On behalf of the Pacific Rivers Council and Center for Biological Diversity, we are writing to express our concerns about the state’s fish hatchery and stocking system and to recommend needed changes that will ensure that the system does not negatively impact California’s native biological diversity. This letter is an update to our letter of August 31, 2005. With this letter, we are enclosing many of the scientific studies we relied on in developing this letter. Fish hatcheries and the stocking of fish into lakes and streams cause numerous measurable, significant environmental effects on California ecosystems. Based on these impacts, numerous policy changes are needed to ensure that the Department of Fish and Game’s (“DFG”) operation of the state’s hatchery and stocking program do not adversely affect California’s environment. Further, as currently operated, the state’s hatchery and stocking program do not comply with the California Environmental Quality Act, Administrative Procedures Act, California Endangered Species Act, and federal Endangered Species Act. The impacts to California’s environment, and needed policy changes to bring the state’s hatchery and stocking program into compliance with applicable state and federal laws, are described below. I. FISH STOCKING NEGATIVELY IMPACTS CALIFORNIA’S NATIVE SALMONIDS, INCLUDING THREATENED AND ENDANGERED SPECIES Introduced salmonids negatively impact native salmonids in a variety of ways. Moyle, et. al. (1996) notes that “Introduction of non-native fish species has also been the single biggest factor associated with fish declines in the Sierra Nevada.” Moyle also notes that introduced species are contributing to the decline of 18 species of native Sierra Nevada fish species, and are a major factor in the decline of eight of those species. -

Kawaiisu Basketry

Kawaiisu Basketry MAURICE L. ZIGMOND HERE are a number of fine basket Adam Steiner (died 1916), assembled at least 1 makers in Kern County, Califomia," 500 baskets from the West, and primarily from wrote George Wharton James (1903:247), "No Cahfornia, but labelled all those from Kern attempt, as far as I know, has yet been made to County simply "Kem County." They may weU study these people to get at definite knowledge have originated among the Yokuts, Tubatula as to their tribal relationships. The baskets bal, Kitanemuk, or Kawaiisu. Possibly the they make are of the Yokut type, and I doubt most complete collection of Kawahsu ware is whether there is any real difference in their to be found in the Lowie Museum of Anthro manufacture, materials or designs." The hobby pology at the University of Califomia, Berke of basket collecting had reached its heyday ley. Here the specimens are duly labelled and during the decades around the turn of the numbered. Edwin L. McLeod (died 1908) was century. The hobbyists were scattered over the responsible for acquiring this collection. country, and there were dealers who issued McLeod was eclectic in his tastes and, unhke catalogues advertising their wares. A Basket Steiner, did not hmit his acquisitions to items Fraternity was organized by George Wharton having esthetic appeal. James (1903:247) James who, for a one dollar annual fee, sent observed: out quarterly bulletins.^ Undoubtedly the best collection of Kern While some Indian tribes were widely County baskets now in existence is that of known for their distinctive basketry, the deal Mr. -

State of California

Upper Piru Creek Wild Trout Management Plan 2012-2017 State of California Department of Fish and Game Heritage and Wild Trout Program South Coast Region Prepared by Roger Bloom, Stephanie Mehalick, and Chris McKibbin 2012 Table of contents Executive summary .................................................................................. 3 Resource status ........................................................................................ 3 Area description ...................................................................................................... 3 Land ownership/administration ............................................................................... 4 Public access .......................................................................................................... 4 Designations ........................................................................................................... 4 Area maps............................................................................................................... 5 Figure 1. Vicinity map of upper Piru Creek watershed ............................................ 5 Figure 2. Map of upper Piru Creek Heritage and Wild Trout-designated reach....... 6 Fishery description.................................................................................................. 6 Figure 3. Photograph of USGS gaging station near confluence of Piru and Buck creeks ..................................................................................................................... 7 -

Prehistoric Rock Art As an Indicator of Cultural Interaction and Tribal Boundaries in South-Central California

Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 15-28(1991). Prehistoric Rock Art as an Indicator of Cultural Interaction and Tribal Boundaries in South-central California GEORGIA LEE, P.O. Box 6774, Los Osos, CA 93402. WILLIAM D. HYDER, Social Sciences Div., Univ. of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064. XN this paper we explore the use of rock art as images seen under the influence of Datura are an indicator of cultural interaction between mandala forms (i.e., elaborate circular designs) neighboring tribal groups in south-central Cal and tiny dots that surround objects. These forms ifornia. The area is of particular interest are ubiquitous in Chumash rock paintings and because of numerous shared cultural traits, possibly were inspired by drug-induced including a spectacular geometric polychrome phenomena. painting tradition (Steward 1929; Fenenga 1949; While much more can be written about rock Grant 1965). Although there can be no doubt art, we do not attempt in this paper to answer that people of this region formed linguistically questions concerning the meaning of the art, its distinct ethnic groups, the interaction between myriad functions in society, or problems of them involved much more than shared elements dating. Our focus lies instead in exploring the of material culture; they also shared some ways and means to use rock painting styles to religious beliefs (Hudson and Blackburn 1978). identify cultural interaction and tribal bound Thus, rock art, as one indicator of ideological aries. systems, provides an important piece of evidence In reference to artistic styles, geometric for the investigation of cultural interaction in figures not only are found throughout the area, south-central California (cf. -

The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River

The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River Mark Q. Sutton and David D. Earle Abstract century, although he noted the possible survival of The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River, little documented by “perhaps a few individuals merged among other twentieth century ethnographers, are investigated here to help un- groups” (Kroeber 1925:614). In fact, while occupation derstand their relationship with the larger and better known Moun- tain Serrano sociopolitical entity and to illuminate their unique of the Mojave River region by territorially based clan adaptation to the Mojave River and surrounding areas. In this effort communities of the Desert Serrano had ceased before new interpretations of recent and older data sets are employed. 1850, there were survivors of this group who had Kroeber proposed linguistic and cultural relationships between the been born in the desert still living at the close of the inhabitants of the Mojave River, whom he called the Vanyumé, and the Mountain Serrano living along the southern edge of the Mojave nineteenth century, as was later reported by Kroeber Desert, but the nature of those relationships was unclear. New (1959:299; also see Earle 2005:24–26). evidence on the political geography and social organization of this riverine group clarifies that they and the Mountain Serrano belonged to the same ethnic group, although the adaptation of the Desert For these reasons we attempt an “ethnography” of the Serrano was focused on riverine and desert resources. Unlike the Desert Serrano living along the Mojave River so that Mountain Serrano, the Desert Serrano participated in the exchange their place in the cultural milieu of southern Califor- system between California and the Southwest that passed through the territory of the Mojave on the Colorado River and cooperated nia can be better understood and appreciated. -

The Supernatural World of the Kawaiisu by Maurice Zigmond1

The Supernatural World of the Kawaiisu by Maurice Zigmond1 The most obvious characteristic at the supernatural world of the Kawaiisu is its complexity, which stands in striking contrast to the “simplicity” of the mundane world. Situated on and around the southern end of the Sierra Nevada mountains in south - - central California, the tribe is marginal to both the Great Basin and California culture areas and would probably have been susceptible to the opprobrious nineteenth century term, ‘Diggers’ Yet, if its material culture could be described as “primitive,” ideas about the realm of the unseen were intricate and, in a sense, sophisticated. For the Kawaiisu the invisible domain is tilled with identifiable beings and anonymous non-beings, with people who are half spirits, with mythical giant creatures and great sky images, with “men” and “animals” who are localized in association with natural formations, with dreams, visions, omens, and signs. There is a land of the dead known to have been visited by a few living individuals, and a netherworld which is apparently the abode of the spirits of animals - - at least of some animals animals - - and visited by a man seeking a cure. Depending upon one’s definition, there are apparently four types of shamanism - - and a questionable fifth. In recording this maze of supernatural phenomena over a period of years, one ought not be surprised to find the data both inconsistent and contradictory. By their very nature happenings governed by extraterrestrial fortes cannot be portrayed in clear and precise terms. To those involved, however, the situation presents no problem. Since anything may occur in the unseen world which surrounds us, an attempt at logical explanation is irrelevant. -

Gazetteer of Surface Waters of California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTI8 SMITH, DIEECTOE WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 296 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS OF CALIFORNIA PART II. SAN JOAQUIN RIVER BASIN PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OP JOHN C. HOYT BY B. D. WOOD In cooperation with the State Water Commission and the Conservation Commission of the State of California WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1912 NOTE. A complete list of the gaging stations maintained in the San Joaquin River basin from 1888 to July 1, 1912, is presented on pages 100-102. 2 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS IN SAN JOAQUIN RIYER BASIN, CALIFORNIA. By B. D. WOOD. INTRODUCTION. This gazetteer is the second of a series of reports on the* surf ace waters of California prepared by the United States Geological Survey under cooperative agreement with the State of California as repre sented by the State Conservation Commission, George C. Pardee, chairman; Francis Cuttle; and J. P. Baumgartner, and by the State Water Commission, Hiram W. Johnson, governor; Charles D. Marx, chairman; S. C. Graham; Harold T. Powers; and W. F. McClure. Louis R. Glavis is secretary of both commissions. The reports are to be published as Water-Supply Papers 295 to 300 and will bear the fol lowing titles: 295. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part I, Sacramento River basin. 296. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part II, San Joaquin River basin. 297. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part III, Great Basin and Pacific coast streams. 298. Water resources of California, Part I, Stream measurements in the Sacramento River basin. -

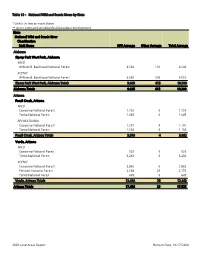

Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/17/2020 Table 13 - National Wild and Scenic Rivers by State

Table 13 - National Wild and Scenic Rivers by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary development State National Wild and Scenic River Classification Unit Name NFS Acreage Other Acreage Total Acreage Alabama Sipsey Fork West Fork, Alabama WILD William B. Bankhead National Forest 6,134 110 6,244 SCENIC William B. Bankhead National Forest 3,550 505 4,055 Sipsey Fork West Fork, Alabama Totals 9,685 615 10,300 Alabama Totals 9,685 615 10,300 Arizona Fossil Creek, Arizona WILD Coconino National Forest 1,720 0 1,720 Tonto National Forest 1,085 0 1,085 RECREATIONAL Coconino National Forest 1,137 4 1,141 Tonto National Forest 1,136 0 1,136 Fossil Creek, Arizona Totals 5,078 4 5,082 Verde, Arizona WILD Coconino National Forest 525 0 525 Tonto National Forest 6,234 0 6,234 SCENIC Coconino National Forest 2,862 0 2,862 Prescott National Forest 2,148 25 2,173 Tonto National Forest 649 0 649 Verde, Arizona Totals 12,418 25 12,443 Arizona Totals 17,496 29 17,525 2020 Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/17/2020 Table 13 - National Wild and Scenic Rivers by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary development State National Wild and Scenic River Classification Unit Name NFS Acreage Other Acreage Total Acreage Arkansas Big Piney Creek, Arkansas SCENIC Ozark National Forest 6,448 781 7,229 Big Piney Creek, Arkansas Totals 6,448 781 7,229 Buffalo, Arkansas WILD Ozark National Forest 2,871 0 2,871 SCENIC Ozark National Forest 1,915 0 1,915 Buffalo, Arkansas Totals 4,785 0 4,786 -

Tejon Conservation Deal Ends Years of Disagreement

California Real Estate Journal: Print | Email MAY 27, 2008 | CREJ FRONT PAGE Reprint rights Tejon Conservation Deal Ends Years of Disagreement 240,000 acres of the ranch will be preserved through conservation easements and project open spaces By KARI HAMANAKA CREJ Staff Writer Two sides of a very public battle pitting Tejon Ranch Co. with five environmental groups led by the Natural Resources Defense Council ended May 8 with the announcement of an agreement to preserve 240,000 acres of land. "This is one of the greatest conservation achievements in California in a very long time," said Joel Reynolds, senior attorney and director of the NRDC's Southern California Program, "and it's because of the vast scale of the property, the unique convergence of ecosystems on the Tejon Ranch, the creation of a new conservancy to manage and restore the land and the commitment by all sides on significant public access to the land. Taken together, this is an extraordinary agreement with an enormous public benefit." The conservation agreement ends talks that began more than two years ago when Tejon Ranch Co. unveiled its development plans for the 270,000-acre property it owns. In a not-so-uncommon story of the somewhat antagonistic relationship between developers and environmental groups, the conservation agreement shows the challenges in reaching a compromise. Upon announcing the agreement between the two groups, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger referred to the deal as historic. "Environmental activists and businesses must sit down and work out their differences in the best interest of California," Schwarzenegger said in a statement. -

Mammalian Species Surveys in the Acquisition Areas on the Tejon Ranch, California

MAMMALIAN SPECIES SURVEYS IN THE ACQUISITION AREAS ON THE TEJON RANCH, CALIFORNIA PREPARED FOR THE TEJON RANCH CONSERVANCY Prepared by: Brian L. Cypher, Christine L. Van Horn Job, Erin N. Tennant, and Scott E. Phillips California State University, Stanislaus Endangered Species Recovery Program One University Circle Turlock, CA 95382 August 16, 2010 esrp_2010_TejonRanchsurvey.doc MAMMALIAN SPECIES SURVEYS IN THE ACQUISITION AREAS ON THE TEJON RANCH, CALIFORNIA TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Study Areas ......................................................................................................................... 3 Methods............................................................................................................................... 4 Target Special Status Species .................................................................................................................... 4 Camera Station Surveys ............................................................................................................................. 4 Live-Trapping ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Spotlight Surveys ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Opportunistic Observations ...................................................................................................................... -

Phase I Proposed Finding—Fernandeño Tataviam Band

Phase I - Negative Proposed Finding Femandefi.o Tataviam Band of Mission Indians Prepared in Response to the Petition Submitted to the Assistant Secretary - Indian Affairs for Federal Acknowledgment as an Indian Tribe w.~R.LeeFleming Director Office of Federal Acknowledgment TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 2 Regulatory Procedures ................................................................................................................. 2 Summary of Administrative Action ............................................................................................ 3 Membership Lists ........................................................................................................................ 4 CONCLUSIONS UNDER THE CRITERIA (25 CFR PART 83.11) ............................................ 5 Criterion 83.11(d) ........................................................................................................................ 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 6 Governing Document ............................................................................................................... 6 Governance..............................................................................................................................