A Case Study of the Implementation of Regulated Midwifery in Manitoba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sars and Public Health in Ontario

THE SARS COMMISSION INTERIM REPORT SARS AND PUBLIC HEALTH IN ONTARIO The Honourable Mr. Justice Archie Campbell Commissioner April 15, 2004 INTERIM REPORT ♦ SARS AND PUBLIC HEALTH IN ONTARIO Table of Contents Table of Contents Dedication Letter of Transmittal EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................1 1. A Broken System .....................................................................................................................24 2. Reason for Interim Report .....................................................................................................25 3. Hindsight...................................................................................................................................26 4. What Went Right?....................................................................................................................28 5. A Constellation of Problems..................................................................................................30 Problem 1: The Decline of Public Health ...............................................................................32 Problem 2: Lack of Preparedness: The Pandemic Flu Example..........................................37 Problem 3: Lack of Transparency.............................................................................................47 Problem 4: Lack of Provincial Public Health Leadership .....................................................51 Problem 5: Lack of Perceived -

Engaging Canadians in a Sustainable Electricity Future

Canadian Electricity Association ELECTRICITY 08 2008 - Volume 79 - Number 1 ENGAGING CANADIANS IN A SUSTAINABLE ELECTRICITY FUTURE www.canelect.ca Message from Don Lowry CEA Chair President and CEO, CEA’s Chair EPCOR Utilities Inc. Canada’s electricity sector is engaging in a wide-ranging public policy debate that will shape how power is produced, delivered and sold for generations to come. Table of Contents The debate touches on critical issues in environmental regulation, long-term energy security, Engaging Canadians in a economic competitiveness and infrastructure reliability. None of these issues can be effectively Sustainable Electricity Future . 3 addressed in isolation, and each one must be considered when planning how we will meet Canada’s future demand for electricity. Risk Management: The Key to Sustainable Both Canada and the United States are experiencing growing economies and rising populations, Resource Management . 9 with consequential increases in electricity demand. Canadians, for example, already consume 21% more power today than we did 15 years ago and our population is forecast to reach CEA Member 40 million by 2030. Projections in both Canada and the United States call for a 25% increase Utility Profiles . 14 in generation capacity by 2025. AltaLink . 15 As an industry, we have a strong record of providing power when needed and our goal is to ATCO Electric . 16 continue to do so in the future. But in many North American regions new power generation ATCO Power . 17 is not keeping pace with growth. Construction is lagging behind demand due to uncertainties BC Hydro . 18 about environmental policy and transmission availability, regulatory processes that are prolonged by ineffective stakeholder engagement, and the impact of rising costs and scarce BC Transmission Corporation . -

Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board 61St Annual Report for the Year Ended March 31, 2012

Needs For and Alternatives To APPENDIX I Manitoba Hydro‐Electric Board 61st Annual Report This page is intentionally left blank. our focus Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board 61st Annual Report For the Year Ended March 31, 2012 AR_2012_cover.indd 1 12-07-11 1:24 PM CORPORATE PROFILE VISION CORPORATE GOALS Manitoba Hydro is one of the largest To be the best utility in North • Improve safety in the workplace. integrated electricity and natural gas America with respect to safety, rates, • Provide exceptional customer value. distribution utilities in Canada. We reliability, customer satisfaction and • Strengthen working relationships provide reliable, affordable energy to environmental leadership; and to with Aboriginal peoples. customers throughout Manitoba and always be considerate of the needs • Maintain financial strength. trade electricity within three wholesale of customers, employees • Extend and protect access to North markets in the Midwestern United and stakeholders. American energy markets and States and Canada. We are also a leader profitable export sales. in promoting conservation, providing MISSION • Attract, develop and retain a highly numerous Power Smart* programs to To provide for the continuance of a skilled and motivated workforce help our customers get supply of energy to meet the needs of that reflects the demographics of the most out of their energy. the province and to promote economy Manitoba. and efficiency in the development, • Protect the environment in everything Nearly all of the electricity Manitoba generation, transmission, distribution, that we do. Hydro produces each year is clean, supply and end-use of energy. • Promote cost effective energy renewable power generated using the conservation and innovation. -

REACHING NEW HEIGHTS Differentiation and Transformation in Higher Education

REACHING NEW HEIGHTS Differentiation and transformation in higher education November 2013 0 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Supporting differentiation in higher education ............................................................................................ 3 Transforming higher education .................................................................................................................... 5 Collaboration and pathways for students..................................................................................................... 6 1. Expanding college degree programs ..................................................................................................... 6 Three-year college degrees ................................................................................................................... 7 Four-year degree programs .................................................................................................................. 7 Stand-alone nursing degrees ................................................................................................................ 8 Approval process for college degrees ................................................................................................... 9 2. A full continuum of opportunities......................................................................................................... 9 -

Ontario-Québec Electricity Collaboration and Interprovincial

Ontario-Québec electricity collaboration and interprovincial trade barriers: using the Agreement on Internal Trade to promote a more sustainable electricity sector in Canada Zachary D’Onofrio 31 March 2016 A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto Ontario, Canada ________________ __________________ Student Signature Supervisor Signature Zachary D’Onofrio Mark Winfield Abstract The purpose of this major paper is to examine the potential for the Agreement on Internal Trade (“AIT”) to facilitate electricity trade between the provinces of Ontario and Québec. The AIT covers a wide range of topics, but its chapter on energy was never completed. The principle objective of this paper is to identify current interprovincial trade barriers in the electricity sector and determine whether the addition of an energy chapter to the AIT would be a viable method of minimizing those barriers. In recent months, importing electricity from Québec has been increasingly recognized as an alternative to building electricity production infrastructure in Ontario. Two recent workshops in Toronto and Montréal identified a number of potential benefits that could be achieved through greater electricity collaboration between the two provinces. These include technical benefits such as greater flexibility and the balancing of intermittent renewable energy resources; economic benefits from a price somewhere between what Québec currently receives for its electricity exports to the Northeastern United States and the price that Ontario is planning to pay for its nuclear refurbishments; and the political opportunity to act cooperatively in demonstrating leadership on the issue of climate change. -

Patient Wait Times Guarantee Project

2008 PATIENT WAIT TIMES GUARANTEE PROJECT A Policy Issue Paper on Manitoba First Nations Foot Care Services Saint Elizabeth Health Care & The Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs PATIENT WAIT TIMES GUARANTEE PROJECT September 30, 2008 PROJECT TITLE This project is entitled “A Policy Issue Paper on Manitoba First Nation Foot Care Services” DEFINITIONS The following clinical terms are used in the document and defined here to ensure common understanding. Podiatry/chiropody: The medical care and treatment of the human foot. This care is provided by Podiatrists or Chiropodists. Pedorthist: An allied health professional specializing in therapeutic footwear. Orthotist: An allied health professional specializing in orthotics. Orthotic: a device (as a brace or splint) for supporting, immobilizing, or treating muscles, joints, or skeletal parts which are weak, ineffective, deformed, or injured Prosthetist: A specialist in prosthetics Prosthesis: The surgical or dental specialty concerned with the design, construction, and fitting of prostheses Prostheses: An artificial device to replace or augment a missing or impaired part of the body Therapeutic Shoes: Shoes that can be purchased off the shelf but meet the specifications for appropriate fit, based upon a pedorthist’s foot assessment Custom Shoes: Specially made shoes designed to meet a client’s specific need; required when the need cannot be accommodated by modifying an existing shoe. Saint. Elizabeth Health Care & The Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs i PATIENT WAIT TIMES GUARANTEE PROJECT September 30, 2008 -

June 19, 1967

June 19, 1967 childhood shows the man, morning shows the day." Milton the Jews, before, during and following the war had to be EDITORIAL reckoned with. The Commission finally brought a recom- mendation to partition Palestine, making two states, Jewish and Arab. The Zionists were jubilant, the Arabs utterly dismayed. The UN General Assembly voted approval of the Commission's recommendation the same year and the Jewish state came into being, May 1948. This writer remembers a dramatic news-cast given by Lowell Thomas the evening of May 15, 1948. In his inimical GOD AND GEOGRAPHY style he emphasized that for the first time in more than 2000 years, there was a state known as Israel. A bloody conflict between the Arabs and Jews followed in 1948. This tragic war resulted in the displacement of 800,000 to one million Arabs. There was another bloody skirmish in 1956. This tiny nation surrounded by 35 to 40 million Arabs LTHOUGH a teenager, vivid memories recall events sur- with more than 600 miles of unfriendly boundary lines to A rounding Jerusalem in 1917. The capture of Jerusalem the east and south and the Mediterranean sea on the by General Allenbey, after being in the possession of west is now threatened with what is termed extinction, Muslims for more than six centuries, was a singular event being driven into the sea. in the early part of the twentieth century. Palestine was then declared a mandated area of the British Empire. At this writing the conflict is raging with the Security Council of the United Nations striving for a cease-fire. -

2004-2009 Strategic Plan Entire

June 21, 2004 The Honourable Diane McGifford Minister of Advanced Education and Training 156 Legislative Building Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 0V8 Dear Minister McGifford, I am pleased to submit Bringing Together the Past, Present and Future: Building a System of Post-Secondary Education in Northern Manitoba, a Five Year Strategic Plan for the University College of the North as the final report for the work of the UCN Implementation Team. Many people provided support to the UCN Implementation Team, including the members of the Steering Committee, the Elders’ Consultations, the Focus Groups, the people we met during presentations, the staff of Keewatin Community College and Inter-Universities North, KCC President Tony Bos as well as many others in the north. The senior staff of Advanced Education and Training, and other individuals within government have also been a support to the Team in many ways. There is still much to be done. The work is just beginning for the innovation and creativity to be put to use, to implement the visions and dreams of many people. The future is where the challenge will be. With continued cooperation and support, all those dreams of meeting the post-secondary educational needs of northern people, especially the young people, can be met. In working together we can do so much. Yours Sincerely, Don Robertson Chairperson, University College of the North Implementation Team University College of the North Implementation Team Don Robertson, Chair Veronica Dyck, Manager John Burelle Peter Geller Gina Guiboche Heather McRae -

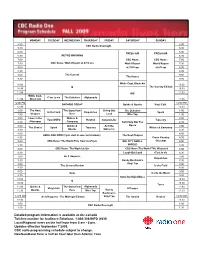

Rev-Radio One F 09

MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00 5:00 CBC Radio Overnight 5:30 5:30 6:00 6:00 FRESH AIR FRESH AIR 6:30 METRO MORNING 6:30 7:00 CBC News: CBC News: 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 6/7/8 am World Report World Report 7:30 8:00 at 7/8/9 am at 8/9 am 8:00 8:30 8:30 9:00 The Current 9:00 The House 9:30 9:30 10:00 White Coat, Black Art 10:00 Q The Sunday Edition 10:30 10:30 11:00 GO! 11:00 White Coat, C'est la vie The Debaters Afghanada 11:30 Black Art 11:30 12:00 PM 12:00 PM ONTARIO TODAY Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 1:00 The Next The Story from Living Out The Debaters 1:00 In the Field Dispatches Spark 1:30 Chapter Here Loud Wire Tap 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Writers & 2:00 Your DNTO Rewind Canada Live Tapestry 2:30 Afternoon Company Definitely Not The 2:30 3:00 Quirks & And the Opera 3:00 The Choice Spark Tapestry Writers & Company 3:30 Quarks Winner Is 3:30 4:00 4:00 HERE AND NOW (3 pm start in selected markets) The Next Chapter 4:30 Cross Country 4:30 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm BIG CITY SMALL Checkup 5:00 5:30 WORLD 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six CBC News:The World This Weekend 6:00 6:30 Laugh Out Loud C'est la vie 6:30 7:00 As It Happens 7:00 Dispatches 7:30 Randy Bachman's 7:30 8:00 Vinyl Tap 8:00 The Current Review In the Field 8:30 8:30 9:00 9:00 Ideas Inside the Music 9:30 9:30 Saturday Night Blues 10:00 10:00 Q 10:30 10:30 Tonic 11:00 Quirks & The Story from Afghanada 11:00 Vinyl Café A Propos 11:30 Quarks Here Wire Tap Randy 11:30 Bachman's 12:00 AM As It Happens - The Midnight Edition Vinyl Tap The Strand Rewind 12:00 AM 12:30 12:30 1:00 1:00 CBC Radio Overnight 1:30 1:30 Detailed program information is available at cbc.ca/radio Toll-free number for Audience Relations: 1-866-306-INFO (4636) Local/Regional news on the half hour from 6 am - 6 pm. -

Aboriginal Learners in Selected Adult Learning Centres in Manitoba by Jim Silver with Darlene Klyne and Freeman Simard

Aboriginal Learners in Selected Adult Learning Centres in Manitoba by Jim Silver with Darlene Klyne and Freeman Simard Executive Summary his is a study of Aboriginal adult learners in five Adult Learning Centres (ALCs) in Mani toba. It is based largely on interviews with 74 Aboriginal Adult Learners and 20 staff Tmembers in the five ALCs. The objective was to determine what keeps Aboriginal adult learners attending ALCs, and what contributes to their successes in ALCs. The research project has been designed and conducted in a collaborative and participatory fashion. It is the product of a research partnership. The partnership includes: the Province of Manitoba’s Aboriginal Education Directorate; the Research and Planning Branch of the Depart- ment of Education and Youth; the Adult Learning and Literacy Branch of the Department of Advanced Education and Training; Directors, teachers and staff at the five Adult Learning Cen- tres; and the authors. All interviews with Aboriginal adult learners were conducted by trained Aboriginal interviewers. Individual interviews were preceded by an initial sharing circle, the pur- pose of which was to introduce adult Aboriginal learners at each site to the research project and the researchers, to solicit their involvement, and to attempt to break down, to some extent, the barriers between researchers and adult learners. Most of the Aboriginal adult learners that we interviewed feel comfortable in the Adult Learn- ing Centre that they are attending, and a significant proportion are experiencing considerable -

Charmaine Andrea Nelson (Last Updated 4 December 2020)

Charmaine Andrea Nelson (last updated 4 December 2020) Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada e-mail: [email protected] Website: blackcanadianstudies.com Table of Contents Permanent Affiliations - 2 Education - 2 Major Research Awards, Fellowships & Honours - 3 Other Awards, Fellowships & Honours – 4 Research - 5 Research Grants and Scholarships - 5 Publications - 9 Lectures, Conferences, Workshops – 18 Keynote Lectures – 18 Invited Lectures: Academic Seminars, Series, Workshops – 20 Refereed Conference Papers - 29 Invited Lectures: Public Forums – 37 Museum & Gallery Lectures – 42 Course Lectures - 45 Teaching - 50 Courses - 50 Course Development - 59 Graduate Supervision and Service - 60 Administration/Service - 71 Interviews & Media Coverage – 71 Blogs & OpEds - 96 Interventions - 99 Conference, Speaker & Workshop Organization - 100 University/Academic Service: Appointments - 103 University/Academic Service: Administration - 104 Committee Service & Seminar Participation - 105 Forum Organization and Participation - 107 Extra-University Academic Service – 108 Qualifications, Training and Memberships - 115 Related Cultural Work Experience – 118 2 Permanent Affiliations 2020-present Department of Art History and Contemporary Culture NSCAD, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada Professor of Art History and Tier I Canada Research Chair in Transatlantic Black Diasporic Art and Community Engagement/ Founding Director - Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery: research, administrative duties, teaching (1 half course/ year): undergraduate and MA -

Indigenous Health

Canadian Sept./Oct., 2019 Physiotherapy Vol. 9, No. 5 Association Indigenous Health Publication Mail Agreement No. 40065308 No. Mail Agreement Publication PLUS: Don’t get hooked! Phishing emails are an ever-present risk OrthoCanada_BTL_ENGLISH_TRIAL.pdf 3 7/9/2019 3:11:21 PM Try the BTL Shockwave for 3 weeks! Visit info.orthocanada.com/swt-trial for more details. Rosen Kolev PT, Senior Instructor Shockwave Training Canada “I’m proud to represent OrthoCanada because I believe in BTL 6000 their product.” Topline Power Mélodie Daoust, Member of Canadian Shockwave with Women’s Olympic Hockey Team, two-time optional cart Olympic Medalist, Olympic Tournament Most Valuable Player 2018 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K BTL World's Most Advanced Modalities Shockwave is an acoustic wave carrying high energy to painful areas and soft tissues with subacute, subchronic and chronic conditions. This energy promotes healing and the regenerating and reparative processes. It’s a unique, non-invasive solution for pain associated with the musculoskeletal system. The BTL 6000 is an accessible, aordable and ecient unit. One of the most powerful, compact Shockwave therapy devices available. THE PHYSIO EQUIPMENT EXPERTS ORTHOCANADA.COM 1-800-561-0310 OrthoCanada_BTL_ENGLISH_TRIAL.pdf 3 7/9/2019 3:11:21 PM September/October 2019 | Vol. 9 / Issue 5 Try the BTL Shockwave for 3 weeks! Visit info.orthocanada.com/swt-trial for more details. Rosen Kolev PT, Senior Instructor Shockwave Training Canada “I’m proud to represent OrthoCanada because I believe in BTL 6000 their product.”