10Mohammad Iqbal Khan, 70, Khalabat Township

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa - Daily Flood Report Date (29 09 2011)

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa - Daily Flood Report Date (29 09 2011) SWAT RIVER Boundary 14000 Out Flow (Cusecs) 12000 International 10000 8000 1 3 5 Provincial/FATA 6000 2 1 0 8 7 0 4000 7 2 4 0 0 2 0 3 6 2000 5 District/Agency 4 4 Chitral 0 Gilgit-Baltistan )" Gauge Location r ive Swat River l R itra Ch Kabul River Indus River KABUL RIVER 12000 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Kurram River 10000 Out Flow (Cusecs) Kohistan 8000 Swat 0 Dir Upper Nelam River 0 0 Afghanistan 6000 r 2 0 e 0 v 0 i 1 9 4000 4 6 0 R # 9 9 5 2 2 3 6 a Dam r 3 1 3 7 0 7 3 2000 o 0 0 4 3 7 3 1 1 1 k j n ") $1 0 a Headworks P r e iv Shangla Dir L")ower R t a ¥ Barrage w Battagram S " Man")sehra Lake ") r $1 Amandara e v Palai i R Malakand # r r i e a n Buner iv h J a R n ") i p n Munda n l a u Disputed Areas a r d i S K i K ") K INDUS RIVER $1 h Mardan ia ") ") 100000 li ") Warsak Adezai ") Tarbela Out Flow (Cusecs) ") 80000 ") C")harsada # ") # Map Doc Name: 0 Naguman ") ") Swabi Abbottabad 60000 0 0 Budni ") Haripur iMMAP_PAK_KP Daily Flood Report_v01_29092011 0 0 ") 2 #Ghazi 1 40000 3 Peshawar Kabal River 9 ") r 5 wa 0 0 7 4 7 Kh 6 7 1 6 a 20000 ar Nowshera ") Khanpur r Creation Date: 29-09-2011 6 4 5 4 5 B e Riv AJK ro Projection/Datum: GCS_WGS_1984/ D_WGS_1984 0 Ghazi 2 ") #Ha # Web Resources: http://www.immap.org Isamabad Nominal Scale at A4 paper size: 1:3,500,000 #") FATA r 0 25 50 100 Kilometers Tanda e iv Kohat Kohat Toi R s Hangu u d ") In K ai Map data source(s): tu Riv ") er Punjab Hydrology Irrigation Division Peshawar Gov: KP Kurram Garhi Karak Flood Cell , UNOCHA RIVER $1") Baran " Disclaimers: KURRAM RIVER G a m ") The designations employed and the presentation of b e ¥ Kalabagh 600 Bannu la material on this map do not imply the expression of any R K Out Flow (Cusecs) iv u e r opinion whatsoever on the part of the NDMA, PDMA or r ra m iMMAP concerning the legal status of any country, R ") iv ") e K territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning 400 r h ") ia the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Islamic Republic of Pakistan Tarbela 5 Hydropower Extension Project

Report Number 0005-PAK Date: December 9, 2016 PROJECT DOCUMENT OF THE ASIAN INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT BANK Islamic Republic of Pakistan Tarbela 5 Hydropower Extension Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective December 21, 2015) Currency Unit = Pakistan Rupees (PKR) PKR 105.00 = US$1 US$ = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR July 1 – June 30 ABBRREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AF Additional Financing kV Kilovolt AIIB Asian Infrastructure Investment kWh Kilowatt hour Bank M&E Monitoring & Evaluation BP Bank Procedure (WB) MW Megawatt CSCs Construction Supervision NTDC National Transmission and Consultants Dispatch Company, Ltd. ESA Environmental and Social OP Operational Policy (WB) Assessment PM&ECs Project Management Support ESP Environmental and Social and Monitoring & Evaluation Policy Consultants ESMP Environmental and Social PMU Project Management Unit Management Plan RAP Resettlement Action Plan ESS Environmental and Social SAP Social Action Plan Standards T4HP Tarbela Fourth Extension FDI Foreign Direct Investment Hydropower Project FY Fiscal Year WAPDA Water and Power Development GAAP Governance and Accountability Authority Action Plan WB World Bank (International Bank GDP Gross Domestic Product for Reconstruction and GoP Government of Pakistan Development) GWh Gigawatt hour ii Table of Contents ABBRREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS II I. PROJECT SUMMARY SHEET III II. STRATEGIC CONTEXT 1 A. Country Context 1 B. Sectoral Context 1 III. THE PROJECT 1 A. Rationale 1 B. Project Objectives 2 C. Project Description and Components 2 D. Cost and Financing 3 E. Implementation Arrangements 4 IV. PROJECT ASSESSMENT 7 A. Technical 7 B. Economic and Financial Analysis 7 C. Fiduciary and Governance 7 D. Environmental and Social 8 E. Risks and Mitigation Measures 12 ANNEXES 14 Annex 1: Results Framework and Monitoring 14 Annex 2: Sovereign Credit Fact Sheet – Pakistan 16 Annex 3: Coordination with World Bank 17 Annex 4: Summary of ‘Indus Waters Treaty of 1960’ 18 ii I. -

Junior Religiuos Teacher

MA Islamic Study/Theology/Dars-e-Nizami will be preferred District: Chitral (Posts-2) Scoring Key: Grade wise marks 1st Div: 2nd Div: 3rd Div: Age 25-35 Years 1. (a) Basic qualification Marks 60 S.S.C 15 11 9 Date of Advertisement:- 22-08-2020 2. Higher Qualification Marks (One Step above-7 Marks, Two Stage Above-10 Marks) 10 F.A/FSc 15 11 9 JUNIOR RELIGIOUS TEACHER/THEOLOGY TEACHER BPS-11 (FEMALE) 3. Experience Certificate 15 BA/BSc 15 11 9 4. Interviews Marks 8 MA/MSc 15 11 9 5. Professional Training Marks 7 Total;- 60 44 36 Total;- 100 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR APPOINTMENT TO THE POST OF JUNIOR RELIGIOUS TEACHER/THEOLOGY TEACHER BPS-11 (FEMALE) BASIC QUALIFICATION Higher Qual: SSC FA/FSC BA/BSc M.A/ MS.c S. # on Name/Father's Name and address Total S. # App Remarks Domicile li: 7 Malrks= Total Marks Total Marks Marks Marks Marks Date of Birth of Date Qualification Division Division Division Division Marks Ph.D Marks Marks M.Phil Marks Marks of Experience of Marks Professional/Training InterviewMarksMarks8 One Stage Above7 Stage One Two StageTwoAbove 10 Year of Experience of Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Rukhsar D/O Noor Zamin Khan anderie post office degree college termerghara 1 1 11/10/1993 MA Islamiyat Dir Lower 2nd 11 1st 15 1st 15 2nd 11 52 52 03439700618 Rabia Khurshid D/O Haji Khurshid Afreen Khan Kalakhel Post office kalakhel mastee 2 2 11/20/1991 MA Islamiyat Bannu 1st 15 1st 15 2nd 11 1st 15 56 56 khan Bannu 03369771362 3 3 Aqsa Rani D/O Mumtaz Akhtar Garee shabaz District Tank 03419394249 2/4/1993 -

HR15D16001-Installation of Electric Poles and Wiresat Moh: Azizabad Village Panina (CO MDC Dheenda) 135,000 135,000 128,500 128

DISTRICT Project Description BE 2018-19 Final Budget Releases Expenditure HARIPUR HR15D16001-Installation of Electric Poles and Wiresat Moh: Azizabad Village Panina (CO 135,000 135,000 128,500 128,500 MDC Dheenda) HARIPUR HR15D16002-Provision of 02 No. water bores UC BSKhan. 450,000 450,000 308,250 308,250 HARIPUR HR15D16101-pavement of street & WSS in DW Dheenda 1,015,000 1,015,000 609,086 609,086 HARIPUR HR15D16300-Boring of handpump/ pressure pumps atvillage Pind Gakhra. 150,000 150,000 111,400 111,400 HARIPUR HR15D16500-Provision of bore at KTS Sector # 3 150,000 150,000 150,000 - HARIPUR HR15D16501-"Provison of bores (3 No) at Nara (c/oArif), Alloli (c/o Rab Nawaz) & Jatti Pind 450,000 450,000 450,000 271,232 (c/o Khan Afsar)." HARIPUR HR15D16502-Provision of bore at S/Saleh. 150,000 150,000 150,000 132,375 HARIPUR HR15D16503-Provision of bore at Serikot. 150,000 150,000 150,000 143,430 HARIPUR HR15D16504-"Provision of bore at village Pindori,UC Bakka." 150,000 150,000 150,000 144,000 HARIPUR HR15D16601-Electrification work in Mohra Mohammadonear tube well (CO MDC Dheenda) 350,000 350,000 - - HARIPUR HR16D00009-WSS Moh: Qazi Sahib village Ghandian. 150,000 150,000 134,775 134,775 HARIPUR HR16D00011-WSS Moh: Dhooman village Ghandian. 149,000 149,000 101,603 101,603 HARIPUR HR16D00019-Pavement of streets/ path/ culverts/protection bund etc in different Moh: of 648,889 648,889 648,889 648,889 Kot Najibulah. HARIPUR HR16D00020-Improvement/ extension of WSS in DW KotNajibulah. -

KPK-PDHQ) (219)Result for the Post of Male Warder (BPS - 05) Zone 5 PAKISTAN TESTING SERVICE MERIT LIST MALE (ZONE-5

KPK PRISONS DEPARTMENT (KPK-PDHQ) (219)Result for the post of Male Warder (BPS - 05) Zone 5 PAKISTAN TESTING SERVICE MERIT LIST MALE (ZONE-5) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Higher Total Obtained Marks of Matric Matric Experience Interview Grand Sr # Name Father Name Contact # District Address DOB Height Chest Runnning Higher Qualification Qualification Screening Screening Column Division Marks Marks Marks Total Marks Marks Marks 13+14+17 1 Sayyed Faisal Shah Zaffer Shah 03464404474 Mansehra Village Brat P/o Jinkiari Tehsil And Distt: Mansehra Feb 28 1991 5x9 39-40 pass 1st Division Graduation 70 8 100 52 130 4 134 2 Wajid Bashir Muhammad Bashir 03435876662 Abbottabad Moh Batta Kari Vill Nagribala Po Kala Bagh Nov 10 1990 5x7 34-35 Pass 1st Division Intermediate/HSSC 70 6 100 51 127 6 133 Dharmang Dhodial Argushai Po Dhodial D/T 3 Hassan Sufiyan Muhammad Sufiyan 03175575636 Mansehra Jan 13 1997 5x11 37-39 Pass 1st Division Intermediate/HSSC 70 6 100 53 129 4 133 Mansehra Village Chittian P/O Qalanderabad Tehsil And Distric 4 Bilal Khan Muhammad Younis 03109326326 Abbottabad Jan 15 1992 5x11 34-36 Pass 1st Division Graduation 70 8 100 47 125 5 130 Abbottabad H No 653/2 St No 5 Mohallah Farooq E Azam Kunj 5 Faisal Pervaiz Muhammad Pervaiz 03479730496 Abbottabad Jun 5 1992 5x7 34-36 Pass 1st Division Graduation 70 8 100 46 124 6 130 Qadeem 6 Sami Ullah Khan Abdul Hanan Khan 03145089747 Abbottabad Mohallah Khizer Zai Mirpur Abbottabad Oct 1 1989 5x8 39-40 Pass 2nd Division Masters and Above 53 12 100 58 123 6 129 7 Hamid -

ALIF AILAAN UPDATE April 2014 April at Alif Ailaan

ALIF AILAAN UPDATE April 2014 April at Alif Ailaan • Supporting provincial enrolment campaigns • #DisruptEd - Ideas and Conversations for Innovation in Education • Presenting the Meesaq-e-Ilm (the Teachers’ Charter for Knowledge) to the Punjab Chief Minister • Politicians as problem solvers in education • The role of religious scholars in Pakistan’s education discourse ENROLMENT CAMPAIGN Supporting provincial enrolment campaigns On April 1 Alif Ailaan education activists teamed up with volunteers and local district government officials to run a month-long enrolment campaign across all four provinces and in Azad Jammu and Kashmir. We reached 60 districts in Pakistan and mobilised parents, village elders and tribal leaders. Special emphasis was placed on the importance of educating girls. ENROLMENT CAMPAIGN Azad Jammu and Kashmir The AJK government’s enrolment campaign was launched in Muzaffarabad by Mian Abdul Waheed Khan, Education Minister of Azad Jammu and Kashmir. AJK Education Minister Mian Abdul Waheed Khan at the launch of the enrolment campaign Education activists in Mirpur Seventy children were personally conducted a door-to-door awareness enrolled by Mian Abdul Waheed campaign urging parents and Khan in Khoi Ratta School during community leaders to send their district Kotli’s enrolment activities children to school, reaching 200 people ENROLMENT CAMPAIGN Balochistan Education activists in Balochistan conducted rallies and set up enrolment camps. Rally with school children in Quetta Enrolment camp in tehsil Duki of Loralai Every -

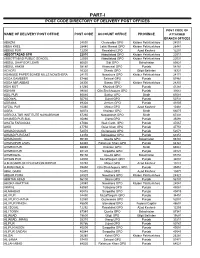

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

U A Z T m B PEACEWA RKS u E JI Bulunkouxiang Dushanbe[ K [ D K IS ar IS TA TURKMENISTAN ya T N A N Tashkurgan CHINA Khunjerab - - ( ) Ind Gilgit us Sazin R. Raikot aikot l Kabul 1 tro Mansehra 972 Line of Con Herat PeshawarPeshawar Haripur Havelian ( ) Burhan IslamabadIslamabad Rawalpindi AFGHANISTAN ( Gujrat ) Dera Ismail Khan Lahore Kandahar Faisalabad Zhob Qila Saifullah Quetta Multan Dera Ghazi INDIA Khan PAKISTAN . Bahawalpur New Delhi s R du Dera In Surab Allahyar Basima Shahadadkot Shikarpur Existing highway IRAN Nag Rango Khuzdar THESukkur CHINA-PAKISTANOngoing highway project Priority highway project Panjgur ECONOMIC CORRIDORShort-term project Medium and long-term project BARRIERS ANDOther highway IMPACT Hyderabad Gwadar Sonmiani International boundary Bay . R Karachi s Provincial boundary u d n Arif Rafiq I e nal status of Jammu and Kashmir has not been agreed upon Arabian by India and Pakistan. Boundaries Sea and names shown on this map do 0 150 Miles not imply ocial endorsement or 0 200 Kilometers acceptance on the part of the United States Institute of Peace. , ABOUT THE REPORT This report clarifies what the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor actually is, identifies potential barriers to its implementation, and assesses its likely economic, socio- political, and strategic implications. Based on interviews with federal and provincial government officials in Pakistan, subject-matter experts, a diverse spectrum of civil society activists, politicians, and business community leaders, the report is supported by the Asia Center at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). ABOUT THE AUTHOR Arif Rafiq is president of Vizier Consulting, LLC, a political risk analysis company specializing in the Middle East and South Asia. -

HR15D16001-Installation of Electric Poles and Wiresat Moh: Azizabad Village Panina (CO MDC Dheenda) 135,000 HR15D16002-Provision

DISTRICT Project Description BE 2018-19 HARIPUR HR15D16001-Installation of Electric Poles and Wiresat Moh: Azizabad Village Panina (CO 135,000 MDC Dheenda) HARIPUR HR15D16002-Provision of 02 No. water bores UC BSKhan. 450,000 HARIPUR HR15D16101-pavement of street & WSS in DW Dheenda 1,015,000 HARIPUR HR15D16300-Boring of handpump/ pressure pumps atvillage Pind Gakhra. 150,000 HARIPUR HR15D16500-Provision of bore at KTS Sector # 3 150,000 HARIPUR HR15D16501-"Provison of bores (3 No) at Nara (c/oArif), Alloli (c/o Rab Nawaz) & Jatti Pind 450,000 (c/o Khan Afsar)." HARIPUR HR15D16502-Provision of bore at S/Saleh. 150,000 HARIPUR HR15D16503-Provision of bore at Serikot. 150,000 HARIPUR HR15D16504-"Provision of bore at village Pindori,UC Bakka." 150,000 HARIPUR HR15D16601-Electrification work in Mohra Mohammadonear tube well (CO MDC Dheenda) 350,000 HARIPUR HR16D00009-WSS Moh: Qazi Sahib village Ghandian. 150,000 HARIPUR HR16D00011-WSS Moh: Dhooman village Ghandian. 149,000 HARIPUR HR16D00019-Pavement of streets/ path/ culverts/protection bund etc in different Moh: of 648,889 Kot Najibulah. HARIPUR HR16D00020-Improvement/ extension of WSS in DW KotNajibulah. 500,000 HARIPUR HR16D00063-"Pavement of Path at Peeli Tarar,Village Ghumawan" 400,000 HARIPUR HR16D00092-Leveling and dressing of Play Ground atVillage Ghari Serian 500,000 HARIPUR HR16D00171-WSS at Village Tiyal 300,000 HARIPUR HR16D00177-Boring of two Hand Pump/Pressure Pump atVillage Jaulian 300,000 HARIPUR HR16D00202-WSS at Kalinjar 78,435 HARIPUR HR16D00210-Boring of pressure pumps -

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Tarbela 5 Hydropower Extension Project, Pakistan

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Tarbela 5 hydropower extension project, Pakistan: Learning the hard lessons from the past? The Tarbela Dam, Pakistan April 2017 Published by Bank Information Center April 2017. This report is supported by Oxfam Hong Kong and written by Kate Geary and Naeem Iqbal. The views expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Oxfam Hong Kong. Cover Image: The Tarbela Dam, Pakistan. Pakistan Game Fish Association. <http://www.pgfa.org> The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Tarbela 5 hydropower extension project, Pakistan: Learning the hard lessons from the past? Project Overview Name: Tarbela 5 Hydropower Extension Project (T5HEP) Location: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan Cost: US$ 823.5 million Investors: WB US$ 390 million; AIIB US$ 300 million; Government of Pakistan US$ 133.5 million Risk: Category A AIIB project approval date: September 2016 Introduction The Tarbela 5 hydropower extension project in Pakistan is one of the first investments made by the world’s newest multilateral bank - the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). There will be much scrutiny of the AIIB’s investments in its first year: how will it differ from existing multilateral development banks? How will the AIIB handle the social and environmental impacts of its first projects? Will this new bank transform the way development is done, or just repeat the mistakes of its predecessors? At first glance, the AIIB’s investment in Tarbela 5 in Pakistan makes perfect sense. Rather than building a new dam, the AIIB – together with the World Bank and Pakistani government – is boosting production at an existing hydro-dam and linking it with new transmission lines to the national grid.1 Project documents point out the benefits: “The Project will provide a low cost, clean, renewable energy option in a relatively short period of time. -

National Trade Corridor Highway Investment Program–Tranche 2 (Package-III: Sarai Saleh–Langra)

Resettlement Plan November 2013 PAK: National Trade Corridor Highway Investment Program–Tranche 2 (Package-III: Sarai Saleh–Langra) Prepared by National Highway Authority, Ministry of Communication, Islamic Republic of Pakistan for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The land acquisition and resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Government of Pakistan Ministry of Communications National Highway Authority D.O. No. E---- 3SAmS/-CAL-s/Airiy dc)f gz-- FRAY W4MwAYS Dated a8- 10- Ro) Ministry of Communications Mr.Jia o Ning Transp rt Specialist, Pakistan Resident Mission, Asian Development Bank Islamabad. Subject: LARP AND LARF OF E-35 PACAKAGE I, II AND III The Land Acquisition Resettlement Framework and Land Acquisition Resettlement Plans for the project of E-35 (Hassanabdal-Havelian- Mansehra) Packages I,II and III, submitted to Asian Development Bank are endorsed for the Bank's concurrence and disclosure. (Yousaf k ) Member (AP) Copy to: • Secretary MOC. • Chairman NHA. • GM (EALS), NHA, HQ. • GM (E-35), NHA, Burhan. • CCAP, NHA, H.Q. • Mr. Ashfaq Khokar, Safeguard Specialist, PRM, ADB. # 27 - Mauve Area, G-911, Islamabad. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 13 November 2013) Currency Unit – Pakistan rupee/s (PRs) PRs1.00 = $0.00944 $1.00 = PRs 105.875 ABBREVIATIONS AD – Assistant Director ADB – Asian Development Bank APs – affected persons COI – Corridor of Impact CBO – Community Based Organization DCR – District Census Report DD – Deputy Director DO(R) – District Officer (Revenue) EDO – Executive District Officer EIA – Environmental Impact Assessment EMP – Environmental Management Plan Ft. -

Compulsory Registration Northern Region

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Revenue Authority (KPRA) Compulsory Registration Northern Region Principal Date of KPRA Comp Date of S.No Order No. Businsess Name Address STATUS KNTN Activities Effect Reg No Comp Reg Glaga, Bagnoter, Cabel 1 04/2019 UFAK CABLE NETWORK, BAGNOTER Feb 14, 19 9835000087 Feb 19, 19 UNREGD #N/A District Abbottabad. Operator Mohalla Londi Cham, Post Office Cabel 2 05/2019 WORLD TOUCH CABLEL NETWORK Feb 14, 19 9835000088 Feb 19, 19 UNREGD #N/A Dhamtore, Tehsil & Operator District Abbottabad Village Dobather, Cabel 3 06/2019 SHIMLA COMMUNICATIONS Mohallah Bagh, Feb 14, 19 9835000089 Feb 19, 19 UNREGD #N/A Operator Abbottabad. Juma Khan, Village Sherwan Kalan, Post Cabel 4 07/2019 LABI KHAN CABLE NETWORK Office Sherwan, Feb 14, 19 9835000090 Feb 19, 19 UNREGD #N/A Operator Tehsil and District Abbottabad. Naveed Ahmed, Village Bigakot, Cabel 5 08/2019 SNA COMMUNICATIONS Union Council Feb 14, 19 9835000091 Feb 19, 19 UNREGD #N/A Operator Kuthiala, Abbottabad. Principal Date of KPRA Comp Date of S.No Order No. Businsess Name Address STATUS KNTN Activities Effect Reg No Comp Reg Mir Alam Market, Opposite GBPS, Cabel 6 10/2019 SHERWAN CABLE NETWORK Feb 14, 19 9835000093 Feb 19, 19 UNREGD #N/A Sherwan Kalan, Operator District Abbottabad. Opposite PTCL Exchange, Post Cabel 7 11/2019 BAKOT CABLE NETWORK, BAKOT Office Butti, Bakot, Feb 14, 19 9835000094 Feb 19, 19 UNREGD #N/A Operator Tehsil & District Abbottabad. Main Bazar Lora Village, Tehsil Cabel 8 12/2019 LORA CABLE NETWORK, LORA, HAVELIAN Feb 14, 19 9835000095 Feb 19, 19 UNREGD #N/A Havelian District Operator Abbottabad.