Mission Report Sweden Iceland.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Hultqvist MINISTRY of DEFENCE

THE SWEDISH GOVERNMENT Following the 2014 change of government, Sweden is governed by the Swedish Social Democratic Party and the Green Party. CURRICULUM VITAE Minister for Defence Peter Hultqvist MINISTRY OF DEFENCE Party Swedish Social Democratic Party Areas of responsibility • Defence issues Personal Born 1958. Lives in Borlänge. Married. Educational background 1977 Hagaskolan, social science programme 1976 Soltorgsskolan, technical upper secondary school 1975 Gylle skola, compulsory school Posts and assignments 2014– Minister for Defence 2011–2014 Chair, Parliamentary Committee on Defence Member, Defence Commission 2010–2011 Group leader, Parliamentary Committee on the Constitution 2009–2014 Board member, Dalecarlia Fastighets AB (owned by HSB Dalarna) 2009–2014 Board member, Bergslagens Mark och Trädgård AB (owned by HSB Dalarna) 2009–2014 Chair, HSB Dalarna economic association 2009– Alternate member, Swedish Social Democratic Party Executive Committee 2006–2010 Member, Parliamentary Committee on Education 2006–2014 Member of the Riksdag 2005–2009 Member, National Board of the Swedish Social Democratic Party 2002–2006 Chair, Region Dalarna – the Regional Development Council of Dalarna County 2001–2005 Alternate member, National Board of the Swedish Social Democratic Party 2001– Chair, Swedish Social Democratic Party in Dalarna 1999–2006 Board member, Borlänge Energi AB 1999–2006 Chair, Koncernbolaget Borlänge Kommun (municipality group company) Please see next page 1998–2006 Municipal Commissioner in Borlänge, Chair of the Municipal -

"Online" Application the Candidates Need to Logon to the Website and Click Opportunity Button and Proceed As Given Below

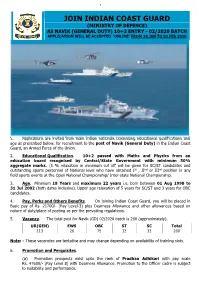

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2020 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 26 JAN TO 02 FEB 2020 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with Maths and Physics from an education board recognised by Central/State Government with minimum 50% aggregate marks. (5 % relaxation in minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports personnel of National level who have obtained Ist , IInd or IIIrd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Inter-state National Championship. 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. born between 01 Aug 1998 to 31 Jul 2002 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits. On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay of Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the prevailing regulations. 5. Vacancy. The total post for Navik (GD) 02/2020 batch is 260 (approximately). UR(GEN) EWS OBC ST SC Total 113 26 75 13 33 260 Note: - These vacancies are tentative and may change depending on availability of training slots. 6. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist upto the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. -

Join Indian Coast Guard (Ministry of Defence) As Navik (General Duty) 10+2 Entry - 02/2018 Batch Application Will Be Accepted ‘Online’ from 24 Dec 17 to 02 Jan 18

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2018 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 24 DEC 17 TO 02 JAN 18 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age, as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with 50% marks aggregate in total and minimum 50% aggregate in Maths and Physics from an education board recognized by Central/State Government. (5 % relaxation in above minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports person of National level who have obtained 1st, 2nd or 3rd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Interstate National Championship. This relaxation will also be applicable to the wards of Coast Guard uniform personnel deceased while in service). 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. between 01 Aug 1996 to 31 Jul 2000 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits:- On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the regulation enforced time to time. 5. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist up to the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. 47600/- (Pay Level 8) with Dearness Allowance. -

Submission-Mare-Liberum

1 Submission to the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants: pushback practices and their impact on the human rights of migrants by Mare Liberum Mare Liberum is a Berlin based non-profit-association, that monitors the human rights situation in the Aegean Sea with its own ships - mainly of the coast of the Greek island of Lesvos. As independent observers, we conduct research to document and publish our findings about the current situation at the European border. Since March 2020, Mare Liberum has witnessed a dramatic increase in human rights violations in the Aegean, both at sea and on land. Collective expulsions, commonly known as ‘pushbacks’, which are defined under ECHR Protocol N. 4 (Article 4), have been the most common violation we have witnessed in 2020. From March 2020 until the end of December 2020 alone, we counted 321 pushbacks in the Aegean Sea, in which 9,798 people were pushed back. Pushbacks by the Hellenic Coast Guard and other European actors, as well as pullbacks by the Turkish Coast Guard are not a new phenomenon in the Aegean Sea. However, the numbers were significantly lower and it was standard procedure for the Hellenic Coast Guard to rescue boats in distress and bring them to land where they would register as asylum seekers. End of February 2020 the political situation changed dramatically when Erdogan decided to open the borders and to terminate the EU-Turkey deal of 2016 as a political move to create pressure on the EU. Instead of preventing refugees from crossing the Aegean – as it was agreed upon in the widely criticised EU-Turkey deal - reports suggested that people on the move were forced towards the land and sea borders by Turkish authorities to provoke a large number of crossings. -

The Professionalisation of the Indonesian Military

The Professionalisation of the Indonesian Military Robertus Anugerah Purwoko Putro A thesis submitted to the University of New South Wales In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences July 2012 STATEMENTS Originality Statement I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Copyright Statement I hereby grant to the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I retain all property rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Authenticity Statement I certify that the Library deposit digital copy is a direct equivalent of the final officially approved version of my thesis. -

The Cable November 2017

1993 - 2017 IUSS / CAESAR The Cable Official Newsletter of the IUSS CAESAR Alumni Association Alumni Association NOVEMBER 2017 ONE LAST DIRECTOR’S CORNER WARM GREETINGS TO ALL IUSS ALUMNI! Jim Donovan, CAPT, USN (Ret) Becky Badders, LCDR, USN (Ret) What an incredible “System” of Navy professionals and patriots I have come to be associated with over these past 45 years. And to Please allow me as your new Alumni think, we’re still organized and contributing! I have Association Director to introduce myself. I am been honored to be Director of the IUSS CAESAR Lieutenant Commander Rebecca “Becky (Harper)” Alumni Association for the past 10 years when I Badders, United States Navy (Retired), and I spent relieved Ed Dalrymple who held the post since its 1984 through 1997 as an IUSS Officer. Beginning inception for an amazing 15 years. Ed, you’re still with my Midshipman Cruise on USS John Rodgers my hero! DD 983 in CIC, I was fascinated by IUSS!! After I was commissioned, I served on temporary duty at But like all good things this too must come to an NOPF Dam Neck in the summer of 1984, attended end. It’s time for me to move on to allow someone FLEASWTRACEN in Norfolk, OWO training at else, someone with fresh ideas and experiences the Readiness Training Facility at Centerville Beach, opportunity to take over the helm of the IUSSCAA. CA (As part of the last officer class to pass through We have found that individual in LCDR Becky those illustrious doors) and then served my first Badders, USN (Ret). -

Icelandic Coast Guard Icelandicicelandicicelandic Coastcoastcoast Guardguardguard

Icelandic Coast Guard IcelandicIcelandicIcelandic CoastCoastCoast GuardGuardGuard CDRCDR GylfiGylfi GeirssonGeirsson Icelandic Coast Guard TheTheThe IcelandicIcelandicIcelandic IntegratedIntegratedIntegrated SystemSystemSystem •• OneOne JointJoint OperationOperation CentreCentre forfor –– CoastCoast GuardGuard OperationOperation •• MonitoringMonitoring ControlControl andand SurveillanceSurveillance (MCS)(MCS) –– GeneralGeneral PolicingPolicing inin thethe IcelandicIcelandic EEZEEZ –– VesselVessel MonitoringMonitoring SystemSystem (VMS)(VMS) –– FisheriesFisheries MonitoringMonitoring CentreCentre (FMC)(FMC) –– MaritimeMaritime TrafficTraffic ServiceService (MTS)(MTS) •• GlobalGlobal MaritimeMaritime DistressDistress andand SafetySafety SystemSystem •• SingleSingle PointPoint ofof ContactContact forfor allall MaritimeMaritime relatedrelated nonotificationstifications –– SchengenSchengen –– PortPort CallCall –– TransitTransit –– SearchSearch andand RescueRescue (SAR)(SAR) –– EmergencyEmergency responseresponse MCS – VMS – FMC – MTS – SAR All integrated into one single centre Icelandic Coast Guard TheTheThe AreaAreaArea ofofof OperationOperationOperation Icelandic Coast Guard TheThe IcelandicIcelandic EEZ.EEZ. AnAn areaarea ofof 754.000754.000 kmkm 22 TheThe NEAFCNEAFC RegulatoryRegulatory AreaArea onon thethe ReykjanesReykjanes ridgeridge CDR G. Geirsson Icelandic Coast Guard TheThe NEAFCNEAFC RegulatoryRegulatory AreaArea EastEast ofof IcelandIceland Icelandic Coast Guard TheThe Icelandic Icelandic SAR SAR area. area. 1,8 1,8 million million -

115 Fighter Wing

115 FIGHTER WING MISSION LINEAGE 115th Tactical Air Support Wing Redesignated 115th Tactical Fighter Wing Redesignated 115th Fighter Wing STATIONS Truax Field, Madison, WI ASSIGNMENTS WEAPON SYSTEMS Mission Aircraft F-16 Support Aircraft C-26 COMMANDERS BG David HoFF BG Joseph Brandemuehl HONORS Service Streamers Campaign Streamers Armed Forces Expeditionary Streamers Decorations EMBLEM MOTTO NICKNAME OPERATIONS 2003 The 115th Fighter Wing has been in the thick oF things since Sept. 11, 2001. F-16 From the wing’s Madison headquarters at Truax Field were either aloFt or on strip alert constantly in the days and weeks Following the terrorist attacks. On October 8, they assisted NORAD with an emergency situation in midwest airspace. Their role was regularized with the inception oF Operation Noble Eagle and the Oct. 23 mobilization oF 62 personnel. From February through April 2002, six aircraft and 100 personnel deployed to Langley Air Force Base, Va., to Fly combat air patrols over the nation’s capital. The unit’s F-16s remain on round-the-clock alert, 365 days a year. Members oF the 115th Security Forces Squadron were mobilized in October 2001 and sent to Air Force bases in the continental U.S. to support Noble Eagle. The mobilization has since been extended From one year to two. As the tempo oF operations For all security personnel continues extremely high, some squadron members have already deployed to bases in the U.S. and worldwide two or three times. Not only F-16 pilots and crews, and the security Forces, but other unit members played roles as well. -

Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010

Description of document: US Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010 Requested date: 07-August-2010 Released date: 15-August-2010 Posted date: 23-August-2010 Title of document Impersonal Names Index Listing Source of document: Commander U.S. Army Intelligence & Security Command Freedom of Information/Privacy Office ATTN: IAMG-C-FOI 4552 Pike Road Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755-5995 Fax: (301) 677-2956 Note: The IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents INSCOM investigative files that are not titled with the name of a person. Each item in the IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents a file in the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository. You can ask for a copy of the file by contacting INSCOM. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. -

US Military Ranks and Units

US Military Ranks and Units Modern US Military Ranks The table shows current ranks in the US military service branches, but they can serve as a fair guide throughout the twentieth century. Ranks in foreign military services may vary significantly, even when the same names are used. Many European countries use the rank Field Marshal, for example, which is not used in the United States. Pay Army Air Force Marines Navy and Coast Guard Scale Commissioned Officers General of the ** General of the Air Force Fleet Admiral Army Chief of Naval Operations Army Chief of Commandant of the Air Force Chief of Staff Staff Marine Corps O-10 Commandant of the Coast General Guard General General Admiral O-9 Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Vice Admiral Rear Admiral O-8 Major General Major General Major General (Upper Half) Rear Admiral O-7 Brigadier General Brigadier General Brigadier General (Commodore) O-6 Colonel Colonel Colonel Captain O-5 Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Commander O-4 Major Major Major Lieutenant Commander O-3 Captain Captain Captain Lieutenant O-2 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant Lieutenant, Junior Grade O-1 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant Ensign Warrant Officers Master Warrant W-5 Chief Warrant Officer 5 Master Warrant Officer Officer 5 W-4 Warrant Officer 4 Chief Warrant Officer 4 Warrant Officer 4 W-3 Warrant Officer 3 Chief Warrant Officer 3 Warrant Officer 3 W-2 Warrant Officer 2 Chief Warrant Officer 2 Warrant Officer 2 W-1 Warrant Officer 1 Warrant Officer Warrant Officer 1 Blank indicates there is no rank at that pay grade. -

Liberation War of Bangladesh

Bangladesh Liberation War, 1971 By: Alburuj Razzaq Rahman 9th Grade, Metro High School, Columbus, Ohio The Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 was for independence from Pakistan. India and Pakistan got independence from the British rule in 1947. Pakistan was formed for the Muslims and India had a majority of Hindus. Pakistan had two parts, East and West, which were separated by about 1,000 miles. East Pakistan was mainly the eastern part of the province of Bengal. The capital of Pakistan was Karachi in West Pakistan and was moved to Islamabad in 1958. However, due to discrimination in economy and ruling powers against them, the East Pakistanis vigorously protested and declared independence on March 26, 1971 under the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. But during the year prior to that, to suppress the unrest in East Pakistan, the Pakistani government sent troops to East Pakistan and unleashed a massacre. And thus, the war for liberation commenced. The Reasons for war Both East and West Pakistan remained united because of their religion, Islam. West Pakistan had 97% Muslims and East Pakistanis had 85% Muslims. However, there were several significant reasons that caused the East Pakistani people to fight for their independence. West Pakistan had four provinces: Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, and the North-West Frontier. The fifth province was East Pakistan. Having control over the provinces, the West used up more resources than the East. Between 1948 and 1960, East Pakistan made 70% of all of Pakistan's exports, while it only received 25% of imported money. In 1948, East Pakistan had 11 fabric mills while the West had nine. -

Major General Raza Muhammad (Retired)

1 RESUME: MAJOR GENERAL RAZA MUHAMMAD (RETIRED) Major General Raza Muhammad (retired) was commissioned into Pakistan Army, in 1980. He has commanded Infantry Battalion, an Independent Infantry Brigade and an Infantry Division. He has served in plains, mountains, glaciated War Zone, Baluchistan and Kashmir. He has served on deputation in Saudi Arabian Army as well. He has done MPhil in International Relations from National Defence University, where he is presently registered as PhD scholar in the Department of International Relations. General Raza has attended Pakistan Staff Course and Armed Forces War Course. He has also done Staff Course at Leadership Academy of German Armed Forces Hamburg in Germany and Peacekeeping Course for the Decision Makers at USA. He has served on various operational and intelligence assignments, major ones being Brigade Major Infantry Brigade, Chief of Staff of a deployed Corps, Director Military Intelligence Operations and as one of the Director Generals at Headquarters Inter-Services Intelligence. Before retiring he was serving as Additional Secretary in Ministry of Defence Production. On instructional side he has been instructor in Pakistan military Academy, Command and Staff College and National Defence University. 2 General Raza Muhammad retired from service on 27 August 2014. After retirement he served as High Commissioner of Pakistan at Mauritius. Seychelles, Comoros and Madagascar were also accredited to his Ambassadorship. His last assignment was Executive Director in Army Welfare Trust Rawalpindi, from where he retired in March 2019. He is presently appointed as Advisor to President NDU. As PhD Scholar in the Department of International Relations, National Defence University, Islamabad, he has been engaged in teaching in IR, NDU, as a Visiting Faculty since 2018.