Partnership Not Paternalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Anthony Seldon [email protected] L Tel

Dear Dr Rodgers I’m writing to apply for the post of President of the University of the Bahamas. For the last five years, I have been Vice Chancellor (ie President) of the University of Buckingham, Britain’s leading private university, and medical school, founded by Margaret Thatcher in the 1970s. She became Chancellor in the 1990s after she ceased to be Prime Minister. Large numbers of Bahamians are alumni of Buckingham, close to 1000. I travelled out to the Bahamas every year or so I was Vice Chancellor, last visiting just after Hurricane Dorian, and have made a large number of friends in the Bahamas. I would relish making a significant impact for good on the country. My experience to date has I believe eQuipped me well to achieve your strategic objectives, including enhancing financial controls and increasing revenue diversity, boosting UG and PG numbers and engagement, and elevating research, community engagement and national/international profile. Two of my referees are Bahamians. One, Sarah Farrington, is an alumna of Buckingham. The other, financier Kiril Sokoloff, who can also speak about my work on AI and digitalisation in higher education, is not an alumnus. The Bahamas is a country where I feel very much at home. In 2015, I founded the “Universities G20“ a group for presidents of some of the world’s leading private/liberal arts universities. The G20 has a strong focus on the United States, allowing me to build on my close knowledge of and friendships with US university leaders. One of my referees, Grant Cornwell, is President of Rollins University, which was one of the founding members. -

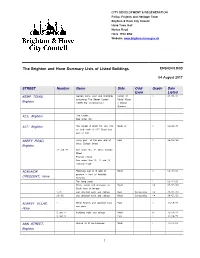

The Brighton and Hove Summary Lists of Listed Buildings ENS/CR/LB/03

CITY DEVELOPMENT & REGENERATION Policy, Projects and Heritage Team Brighton & Hove City Council Hove Town Hall Norton Road Hove BN3 3BQ Website: www.brighton-hove.gov.uk The Brighton and Hove Summary Lists of Listed Buildings ENS/CR/LB/03 04 August 2017 STREET Number Name Side Odd/ Grade Date Even Listed KEMP TOWN, Garden walls, vault and structures Corner of II 04/06/14 comprising The Secret Garden Bristol Place Brighton (NGR TQ 3336003706) / Bristol Gardens The Chattri, A23, Brighton See under A27 A27, Brighton The Chattri at NGR TQ 304 103, North of II 20/08/71 on land north of A27 Road and east of A23 Lamp post at the east end of East II 26/08/99 ABBEY ROAD, Great College Street Brighton 17 and 19 See under No. 53 Great College Street Pearson House See under Nos 12, 13 and 14 Portland Place Retaining wall to S side of South II 02/11/92 ADELAIDE gardens in front of Adelaide CRESCENT, Hove Crescent Ten lamp posts II 02/11/92 Walls, ramps and stairways on South II* 05/05/69 South front of terrace 1-19 and attached walls and railings East Consecutive II* 24/03/50 20-38 and attached walls and railings West Consecutive II* 24/03/50 1 White Knights and attached walls East II 10/09/71 ALBANY VILLAS, and piers Hove 2 and 4 including walls and railings West II 10/09/71 3 and 5 East II 10/09/71 Church of St Bartholomew North I 13/10/52 ANN STREET, Brighton 1 STREET Number Name Side Odd/ Grade Date Even Listed Arundel Place Mews Nos.11 & 12 East II 26/08/99 ARUNDEL PLACE, and attached walls and piers Brighton Arundel Place Mews Units 2, 3, East of II 26/08/99 4, 8, 8A & 9 Lamp post - in front of No.10 East II 26/08/99 NB some properties on Arundel Place may be listed as part of properties on Lewes Crescent or Arundel Terrace. -

Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) Materials

BRIGHTON AND HOVE Moving On 2 A resource to support Year 6 and Year 7 students in developing social and emotional skills for transfer. Healthy Schools Team Hove Park Mansions Hove Park Villas Hove BN3 6HW Tel: 01273 293530 Fax: 01273 295392 E-mail: [email protected] The Healthy Schools Team will provide updates to this resource online Published May 2009 Preface The transfer from primary school to secondary school is a significant event involving many complex emotions. The move ought to be successful for all pupils and we should try to ensure that the process is as smooth as possible. In Brighton & Hove schools there is already much good practice supporting pupils in managing this significant change. The CYPT welcomes wholeheartedly this new resource, Moving On 2. It will provide schools with additional materials for use within the curriculum, ensuring that pupils feel that their primary level achievements are valued and acknowledged, and enabling them to build on those achievements at secondary level. Preface ThisThe transfer resource, from primary school which to secondar yhas school isbeen a significant developed event by Brighton & Hove teachers working with consultants from involving many complex emotions. The move ought to be successf u l for all pupils and we should try to ensure that the process is as smooth as possible. theIn Brighton Advisory & Hove schools Service,there is already much replaces good practice supportingthe Moving On booklet and instead provides a Year 6 unit of work that pupils in managing this significant change. links effective literacy planning to the Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) materials. -

The Power of the Prime Minister

Research Paper Research The Power of the Prime Minister 50 Years On George Jones THE POWER OF THE PRIME MINISTER 50 YEARS ON George Jones Emeritus Professor of Government London School of Economics & Political Science for The Constitution Society Based on a lecture for the Institute of Contemporary British History, King’s College, London, 8 February 2016 First published in Great Britain in 2016 by The Constitution Society Top Floor, 61 Petty France London SW1H 9EU www.consoc.org.uk © The Constitution Society ISBN: 978-0-9954703-1-6 © George Jones 2016. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. THE POWER OF THE PRIME MINISTER 3 Contents About the Author 4 Foreword 5 Introduction 9 Contingencies and Resource Dependency 11 The Formal Remit and Amorphous Convention 13 Key Stages in the Historical Development of the Premiership 15 Biographies of Prime Ministers are Not Enough 16 Harold Wilson 17 Tony Blair – almost a PM’s Department 19 David Cameron – with a department in all but name 21 Hung Parliament and Coalition Government 22 Fixed-term Parliaments Act, 2011 25 Party Dynamics 26 Wilson and Cameron Compared 29 Enhancing the Prime Minister 37 Between Wilson and Cameron 38 Conclusions 39 4 THE POWER OF THE PRIME MINISTER About the Author George Jones has from 2003 been Emeritus Professor of Government at LSE where he was Professor of Government between 1976 and 2003. -

The Return of Cabinet Government? Coalition Politics and the Exercise of Political Power Emma Bell

The Return of Cabinet Government? Coalition Politics and the Exercise of Political Power Emma Bell To cite this version: Emma Bell. The Return of Cabinet Government? Coalition Politics and the Exercise of Political Power. Revue française de civilisation britannique, CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d’études en civilisation britannique, 2017. hal-01662078 HAL Id: hal-01662078 http://hal.univ-smb.fr/hal-01662078 Submitted on 12 Dec 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Return of Cabinet Government? Coalition Politics and the Exercise of Political Power Emma BELL Université de Savoie « The Return of Cabinet Government ? Coalition Politics and the Exercise of Political Power », in Leydier, Gilles (éd.) Revue française de la civilisation britannique, vol. 17, n°1, 2012. Abstract It is often said that political power in the UK is increasingly concentrated in the hands of the Prime Minister and a cadre of unelected advisers, prompting many commentators to announce the demise of Cabinet government. This paper will seek to determine whether or not the advent of coalition government is likely to prompt a return to collective decision-making processes. It will examine the peculiarities of coalition politics, continuities and ruptures with previous government practice and, finally, ask whether or not the return of Cabinet government is realistic or even desirable. -

British Prime Ministers Since World War II | University of Glasgow

09/24/21 British Prime Ministers Since World War II | University of Glasgow British Prime Ministers Since World War II View Online 1 Blick A, Jones GW. Premiership: the development, nature and power of the British prime minister. Exeter: : Imprint Academic 2010. http://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=GlasgowUni&isbn=9781845 406479 2 King AS. The British Prime Minister. 2nd ed. Durham, N.C.: : Duke University Press 1985. 3 Foley M. The British presidency: Tony Blair and the politics of public leadership. Manchester: : Manchester University Press 2000. 4 Childs, David. Britain since 1945: a political history. 7th ed. London: : Routledge 2012. 5 Morgan KO, Ebooks Corporation Limited. Britain since 1945: the people’s peace. Third edition. Oxford: : Oxford University Press 2001. http://GLA.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=886567 6 1/53 09/24/21 British Prime Ministers Since World War II | University of Glasgow A. Sked and Chris Cook. Post-war Britain: a political history. 4th ed. London: : Penguin Books 1993. 7 Alderman RK, Cross JA. Rejuvenating the Cabinet: the Record of Post-war British Prime Ministers Compared. Political Studies 1986;34:639–46. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1986.tb01618.x 8 King A, Allen N. ‘Off With Their Heads’: British Prime Ministers and the Power to Dismiss. British Journal of Political Science 2010;40. doi:10.1017/S000712340999007X 9 Allen N, Ward H. ‘Moves on a Chess Board’: A Spatial Model of British Prime Ministers’ Powers over Cabinet Formation. British Journal of Politics & International Relations 2009;11 :238–58. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2009.00364.x 10 Bevir M, Rhodes RAW. -

Secondary School School Admissions in Brighton & Hove 2016-2017

Secondary School School Admissions in Brighton & Hove 2016-2017 Closing date for applications 31 October 2015 A guide for parents and carers • Transferring to Secondary School • Moving into the area Mandarin If you would like a translation of the information contained in this booklet, please tick the appropriate box and write your name and address below. This formLatvian should then be sent to the School Admissions Team at the address below: 如果您想要一份这本小册子中所包含的信息的翻译版本,请勾选适当的方格,并在下方写上您 The aim of this booklet is to help parents obtain aIf place you would in schoollike a translation of the information contained in this booklet, please tick the appropriate Polish for的姓名 their和 地址child.,然后将本表格寄到以下地址的入学申请小组 It explains the procedure to follow,(Schoolbox the and Admissionstimescales write your Teamname )。and address below. This form should then be sent to the School and what to do if there are any problems or difficulties.Admissions Team at the address below: If a translation is needed, please fill in the form at the Ja jūs vēlaties saņemt bukleta tulkojumu, lūdzu atzīmējiet to attiecīgajā lauciņā un zemāk norādiet backThe aimof the of this booklet booklet and is to posthelp parentsit. obtain a place in school savufor their vārdu child. un adresi. It explains Šo veidlapu the pēc tam nosūtiet Skolas Uzņemšanas nodaļai uz zemāk norādīto If you would like a translation of the information contained in this booklet,adresi: please tick the appropriate procedurebox and write to follow your name and the and timescales address below. and what This to form do if should there are then any be problems sent to the or School difficulties. -

Interview Can Be Accessed Here

e Must Help People Live WPeacefully With Themselves Exclusive Interview with Sir Anthony Seldon Conducted by Bardia Garshasbi in London- February 2016 Sir Anthony Seldon is a prominent British headmaster, historian, and author. Mr. Seldon was the 13th headmaster of the famous “Wellington College” for almost a decade, and prior to that he headed “Brighton College”, which is considered to be one of the most expensive private schools in the UK. Anthony Seldon is a prolific writer and has written over 35 books on politics, contemporary history, and education. He has also co-founded “Center for Contemporary British History”, and “Action for Happiness”. Mr. Seldon is currently Vice-Chancellor of the University of Buckingham in England. Sir Anthony Seldon is an extremely busy person, and I was very lucky I could meet him for this interview on a chilly February night. We met in front the famous Big Ben in Central London and walked along the Palace of Westminster for over half an hour where I could record the interview. He is an exceptionally amicable and soft- speaking man and despite being late for an evening meeting in the Parliament, he answered all my questions patiently. The Excellent Organization 2 Bardia: Mr. Seldon! Everybody loves to know more about the life story of successful people. As a successful man, would you please introduce yourself to our readers? Seldon: Well, for a start, I should say that I am not very successful at all. My father’s parents were Jewish immigrants who had come to the UK from Ukraine and they had both died in the influenza plague at the end of the First World War. -

Secondaryschoolspendinganaly

www.tutor2u.net Analysis of Resources Spend by School Total Spending Per Pupil Learning Learning ICT Learning Resources (not ICT Learning Resources (not School Resources ICT) Total Resources ICT) Total Pupils (FTE) £000 £000 £000 £/pupil £/pupil £/pupil 000 Swanlea School 651 482 1,133 £599.2 £443.9 £1,043.1 1,086 Staunton Community Sports College 234 192 426 £478.3 £393.6 £871.9 489 The Skinners' Company's School for Girls 143 324 468 £465.0 £1,053.5 £1,518.6 308 The Charter School 482 462 944 £444.6 £425.6 £870.2 1,085 PEMBEC High School 135 341 476 £441.8 £1,117.6 £1,559.4 305 Cumberland School 578 611 1,189 £430.9 £455.1 £885.9 1,342 St John Bosco Arts College 434 230 664 £420.0 £222.2 £642.2 1,034 Deansfield Community School, Specialists In Media Arts 258 430 688 £395.9 £660.4 £1,056.4 651 South Shields Community School 285 253 538 £361.9 £321.7 £683.6 787 Babington Community Technology College 268 290 558 £350.2 £378.9 £729.1 765 Queensbridge School 225 225 450 £344.3 £343.9 £688.2 654 Pent Valley Technology College 452 285 737 £339.2 £214.1 £553.3 1,332 Kemnal Technology College 366 110 477 £330.4 £99.6 £430.0 1,109 The Maplesden Noakes School 337 173 510 £326.5 £167.8 £494.3 1,032 The Folkestone School for Girls 325 309 635 £310.9 £295.4 £606.3 1,047 Abbot Beyne School 260 134 394 £305.9 £157.6 £463.6 851 South Bromsgrove Community High School 403 245 649 £303.8 £184.9 £488.8 1,327 George Green's School 338 757 1,096 £299.7 £670.7 £970.4 1,129 King Edward VI Camp Hill School for Boys 211 309 520 £297.0 £435.7 £732.7 709 Joseph -

Gunboat Command A5

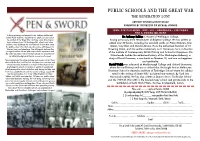

PUBLIC SCHOOLS AND THE GREAT WAR THE GENERATION LOST ANTHONY SELDON & DAVID WALSH FOREWORD BY PROFESSOR SIR MICHAEL HOWARD ISBN: 9781781593080 • RRP: £25 • HARDBACK • 320 PAGES PEN & SWORD MILITARY In this pioneering and original book, Anthony Seldon and David Walsh study the impact that the public schools had on Dr Anthony Seldon is Master of Wellington College, the conduct of the Great War, and vice versa. Drawing on having previously been Headmaster of Brighton College. He has written or fresh evidence from 150 leading public schools and other edited over 30 books, including the standard works on Prime Ministers John archives, they challenge the conventional wisdom that it was the public school ethos that caused needless suffering on the Major, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. He is the authorised historian of 10 Western Front and elsewhere. They distinguish between the Downing Street, and has written extensively on it. Moreover, he is co-founder younger front-line officers with recent school experience and of the Institute of Contemporary British History and Action for Happiness. His the older ‘top brass’ whose mental outlook was shaped more by military background than by memories of school. future books include the authorised history of the Washington Embassy, a study of David Cameron, a new book on Number 10, and one on happiness This poignant and thought-provoking work covers not just those who made the final sacrifice, but also those who returned, and and spirituality. whose lives were shattered as a result of their physical and David Walsh was educated at Marlborough College and Oxford University, psychological wounds. -

Head of Chemistry

BRIGHTON COLLEGE CANDIDATE BRIEF Head of Chemistry 1 THE SCHOOL Brighton is one of England’s leading schools and the oldest public school in Sussex. The College comprises the Senior School, educating 1,000 pupils aged 13–18, and the Lower School, educating 100 pupils aged 11–13. The Brighton College family of schools also includes Brighton College Prep School, St Christopher’s and Handcross Park, educating a further 1,150 children aged 3 to 13. Overseas, the College has opened Brighton College Abu Dhabi, Brighton College Al Ain and Brighton College Dubai in the UAE, and Brighton College Bangkok in Thailand. Examination results are strong and the College is among the highest performing schools in England at GCSE and A-level. In 2018, 90.3% of grades at GCSE were at 9, 8 or 7 (equivalent to the old A* and A), whilst 99% of grades at A-level were at A*, A or B. The last five years have also been the best five for Oxbridge success in the 168-year history of the College, with 37 pupils securing offers in 2018. The Sunday Times awarded Brighton College the title of ‘England’s Independent School of the Year 2018-19’, the second time the College has received this prestigious award in recent years. Tatler magazine awarded Richard Cairns the title of ‘Head Master of the Year 2012-13’. And Brighton College was named the ‘United Kingdom Independent School of the Year 2013-14’ (Independent Schools Awards). In 2014 The Week magazine named Brighton College the “Most Forward Looking School in Britain”. -

The Third Crusade

review Anthony Seldon, Blair Free Press: London 2005, £9.99, paperback 800 pp, 0 743 23212 7 Richard Gott THE THIRD CRUSADE Elections in Britain on 5 May 2005 brought a third victory to Tony Blair’s New Labour party, though with a much reduced majority in parliament, only 35 per cent of the popular vote, and barely a fifth of the overall electorate— the lowest percentage secured by any governing party in recent European history. ‘When regimes are based on minority rule, they lose legitimacy’, Blair had told an audience at the Chicago Economic Club in April 1999. He was thinking at the time of the former Yugoslavia of Slobodan Miloševic´ and of apartheid South Africa, but his warning could now be applied to his own regime. More people abstained from voting in May 2005 than voted Labour. Disgust, rather than apathy, was the root cause of the abstention. Widely celebrated as the first, ‘historic’ occasion on which a Labour government had won three elections in a row, the Blairite success might more relevantly be described as the sixth victory of a British government operating under Thatcherite principles since Margaret Thatcher was elected prime minister in 1979. ‘Almost everything Blair has done personally—in education, health, law and order and Northern Ireland—has also been an extension of Conservative policy between 1979 and 1997’, argues Anthony Seldon in his exhaustive study, Blair, the largest and most useful of the raft of recently published biographies, most of which have been hagiographic but some more critical. Seldon’s charge is difficult to refute, and Blair’s relatively meagre showing in the election of 2005 had much to do with the disillusion of traditional Labour voters, finally obliged to admit that their party had been captured by the proponents of an alien ideology.